Popol Vuh

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article is missing citations or needs footnotes. Please help add inline citations to guard against copyright violations and factual inaccuracies. (May 2007) |

- For other uses, see: Popol Vuh (disambiguation)

The Popol Vuh (K'iche' for "Council Book" or "Book of the Community"; Popol Wu'uj in modern spelling; IPA: [popol wuʔuχ] ) is a book written in the Classical Quiché language containing mythological narratives and a genealogy of the rulers of the Post-Classic Quiché kingdom of highland Guatemala.

The book contains a creation myth followed by mythological stories of two Hero Twins: Hunahpu (Modern K'iche': Junajpu) and Xbalanque (Modern K'iche': Xb‘alanke). The second part of the book deals with details of the foundation and history of the Quiché kingdom, tying in the royal family with the legendary gods in order to assert rule by divine right.

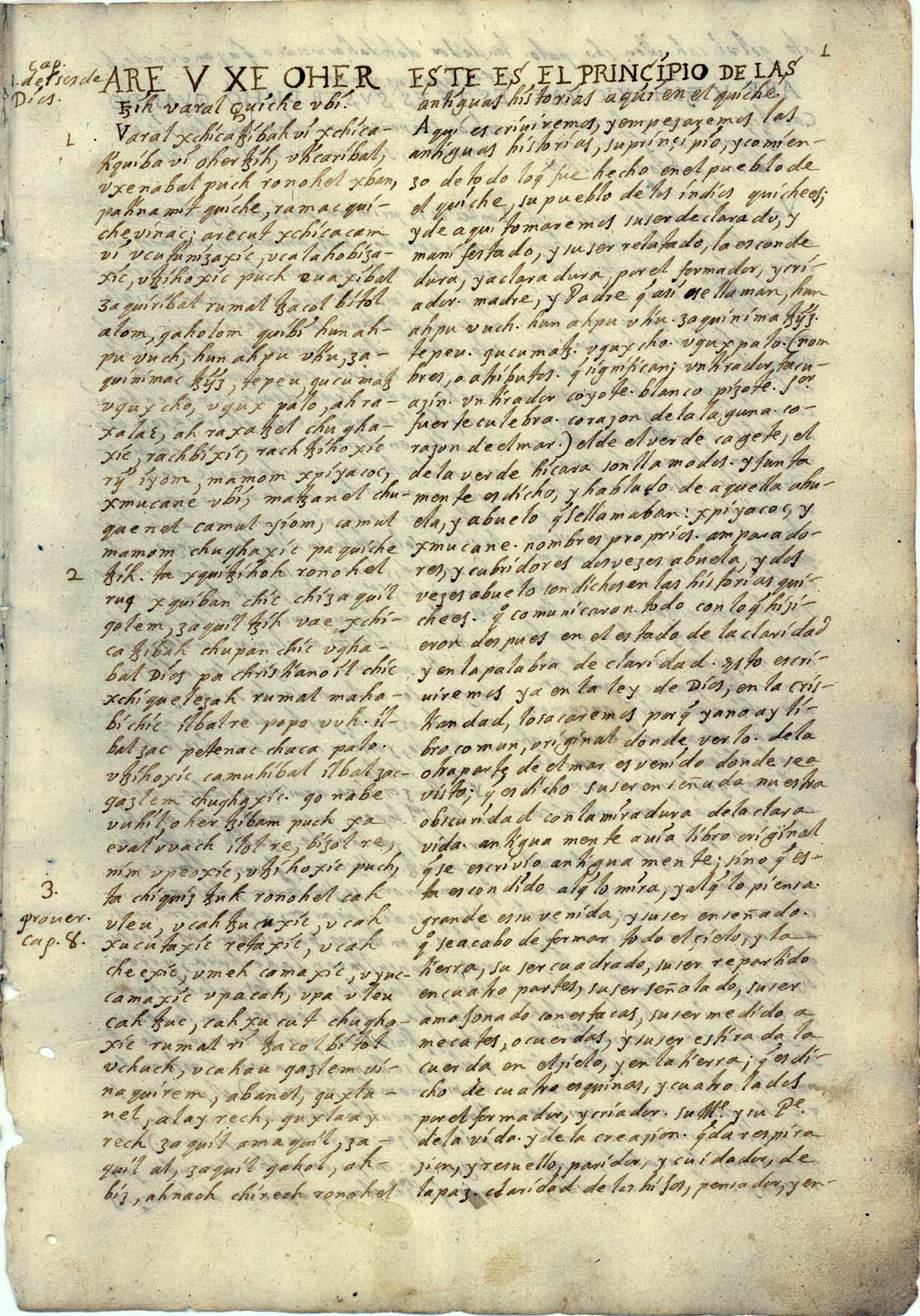

The book is written in the Latin alphabet, but it is thought to have been based on an original Maya codex in the Mayan hieroglyphic script. The original manuscript which was written around 1550 has been lost, but a copy of another handwritten copy made by the Friar Francisco Ximénez in the early 18th century exists today in the Newberry Library in Chicago.

The significance of the book is considerable since it is one of a small number of early Mesoamerican mythological texts. It is often considered the single most important piece of Mesoamerican literature.[citation needed] The mythology of the Quiché is believed to correspond quite closely to that of the Pre-Classic Maya, as depicted in the San Bartolo murals, and iconography from the Classic period often contains motifs that are interpretable as scenes from the Popol Vuh.

Contents |

[edit] History

The original manuscript, which Munro Edmonson and Jack Himelblau have termed "The manuscript of Quiché," was redacted from oral tradition in Santa Cruz del Quiché, Guatemala. Cross-referencing known dated colonial records and the genealogy at the end of Popol Vuh, Dennis Tedlock believes the redaction likely occurred between 1554 and 1558.[1] It is a phonetic transcription of the Quiché oral recitation. It is also possible that there once existed a pre-Columbian text. Michael D. Coe has identified polychrome depictions of portions of the Popol Vuh's storyline. After Pedro de Alvarado's conquest of the Yucatán in 1524, Dominican missionaries were tasked with pacifying the Indians. They taught the Spanish language to the natives, which explains why the Popol Vuh manuscript was written using the phonetic values of the 16th century Spanish alphabet. Judging from the genealogical part of the work, in which a prominent place is given to the Kaweq lineage, the author/scribe/narrator/storyteller may have belonged to this lineage as opposed to the other royal Quiché lineages, the Nijaib lineage, the Tam lineage and the Ilok'ab lineages. Some have speculated that the author was a certain Diego Reynoso, also the author of another Quiché document, the Titulo de Totonicapán. Van Akkeren[2] and many others reject Reynoso as the author of Popol Vuh, since the viewpoint in the Titulo de Totonicapan is biased against the Kaweq lineage – he thinks that the authors were in fact the heads of a faction of the Kaweq lineage called the Nim Ch'okoj.

Whoever the sixteenth century scribe was, the text was closely guarded and passed down among the natives. In 1694, R.P.F. Francisco Ximénez of the Order of Santo Domingo completed his novitiate and was dispatched to work with the natives in Santo Tomás Chichicastenango. Here he gained the trust of the natives and obtained the (or a copy of the) phonetic redaction of Popol Vuh. Ximénez copied and translated the manuscript in parallel columns before, it is believed, returning it to his lender. This transcription-translation was collated with other treatises. When Ximénez died c.1730, his manuscript, as did those of other priests, remained in the possession of the Dominican Order. However, when General Francisco Morazán expelled the clerics from Guatemala in 1829/1830, the Order's documents passed to the Universidad de San Carlos, where Carl Scherzer (also Karl von Scherzer)--one of many European Americanaphiles of his day--found it in 1854. Scherzer notes, "se halla otro volúmen [sic] de las obras del Padre Ximenez [sic] del mayor interes [sic]" and then provides a meticulous description of the contents of this "volumen" (Scherzer:1857, xii-xiv). The contents of his inventory coincide precisely with that of the Newberry Library's Ayer 1515 ms, which has four principal divisions: 1) Arte de las tres lengvas Kakchiqvel, Qvíche y Zvtvhil, 2) Tratado segvndo de todo lo qve deve saber vn mínístro para la buena admínístraçíon de estos natvrales, 3) Empiezan las historias del origen de los indíos de esta proviçia de Guatemala, 4) Escolíos a las hístorías de el orígen de los índíos [note: spelling is that of Ximénez, but capitalization is modified here for stylistic reasons]. With assistance from Juan Gavarete, Scherzer had a copy made of the final two sections. L'Abbé Charles Etienne Brasseur de Bourbourg also found this same manuscript in 1855. In 1857, Scherzer published his mono-lingual Spanish edition as Las Historias del Origen de Los Indios. in 1861, Brasseur published his in bicolumnar Quiché-French edition as Popol Vuh. Le Livre Sacré. This is the first attribution as "Popol Vuh."

Though Munro Edmonson and Jack Himelblau advance a tenuous theory of multiple manuscripts, Nestor Quiroa considers the Newberry Library's Ayer 1515 ms to be Ximénez' "original" as was found by Scherzer and Brasseur. Edmonson and Himelblau base their theory on a literal reading of Brasseur's bibliographic notes in his Histoire des nations civilisées du Mexique et de l'Amerique, in which he [Brasseur] states that he obtained his source material in Rabinal from Ignacio Coloche, a noble "cacique." He reasserts this position in his Bibliothèque Mexico-Guatémalienne. After Brasseur's death in 1874, the Mexico-Guatémalienne collection containing Popol Vuh passed to Alphonse Pinart through whom it was sold to Edward E. Ayer. Ayer donated some 50,000 pieces to The Newberry Library (Chicago, Illinois, USA) over a period from 1897 to 1911. Popol Vuh was among these items.

Since Brasseur de Bourbourg's and Scherzer's first editions, the Popol Vuh has been translated into English and other languages. The Popol Vuh is considered one of the literary treasures of the Americas.

[edit] Contents

[edit] Summary

- This is a very general summary; divisions depend on text version

Part 1

- Gods create world.

- Gods create first "wood" humans; they are imperfect and emotionless.

- Gods destroy first humans in a "resin" flood; they become monkeys.

- Twin diviners Hunahpu & Xbalanque destroy arrogant Vucub-Caquix, then Zipacna & Cabracan.

Part 2

- Diviners Xpiyacoc and Xmucane beget brothers.

- HunHunahpu & Xbaquiyalo beget "Monkey Twins" HunBatz & HunChouen.

- Cruel Xibalba lords kill the brothers HunHunahpu & VucubHunahpu.

- HunHunahpu & Xquic beget "Hero Twins" Hunahpu & Xbalanque.

- "Hero Twins" defeat the Xibalba houses of Gloom, Knives, Cold, Jaguars, Fire, and Bats.

Part 3

- The first four "real" people are made: Balam-Quitze, Jaguar Night, Naught, & Wind Jaguar.

- Tribes descend; they speak the same language and travel to TulanZuiva.

- The tribes language becomes confused, and they disperse.

- Tohil is recognized as a god and demands life sacrifices; later he must be hidden.

Part 4

- Tohil affects Earth Lords through priests, but his dominion destroys the Quiche.

- Priests try to abduct tribes for sacrifices; the tribes try to resist this.

- Quiche finds Gumarcah where Gucumatz (the feathered serpent lord) raises them to power.

- Gucumatz institutes elaborate rituals.

- Genealogies of the tribes

[edit] Creation myth

The book begins with the creation myth of the K'ichee' Maya, which credits the creation of humans to the three water-dwelling feathered serpents:

- There was only immobility and silence in the darkness, in the night. Only the Creator, the Maker, Tepeu, Gucumatz, the Forefathers, were in the water surrounded with light. They were hidden under green and blue feathers, and were therefore called Gucumatz...

and to the three other deities, collectively called "Heart of Heaven":

- Then while they meditated, it became clear to them that when dawn would break, man must appear. Then they planned the creation, and the growth of the trees and the thickets and the birth of life and the creation of man. Thus it was arranged in the darkness and in the night by the Heart of Heaven who is called Huracán. The first is called Caculhá Huracán. The second is ChipiCaculhá. The third is Raxa-Caculhá. And these three are the Heart of Heaven.

who together attempted to create human beings to keep him company.

Their first attempts proved unsuccessful. They attempted to make man of mud, but man could neither move nor speak. After destroying the mud men, they tried again by creating wooden creatures that could speak but had no soul or blood and quickly forgot him. Angered over the flaws in his creation, they destroyed them by tearing them apart. In their final attempt, the “True People” were constructed with maize. The following is an excerpt of this myth:

- They came together in darkness to think and reflect. This is how they came to decide on the right material for the creation of man. ... Then our Makers Tepew and Q'uk'umatz began discussing the creation of our first mother and father. Their flesh was made of white and yellow corn. The arms and legs of the four men were made of corn meal.

[edit] Today

The Popol Vuh continues to be an important part in the belief system of many Quiché. Although most are now Catholic, they continue to blend Christian and indigenous beliefs. The original text is seen as difficult to understand, and a simplified version, Popol Vuh: A Sacred Book of the Maya, has now been published in English, Hungarian, Estonian and Spanish, targeted towards adult and children who are unfamiliar with the Maya.

[edit] Other sources

Classic Maya pottery shows some of the main characters of the mythological part of the document, such as the Maya Hero Twins and the Howler Monkey Gods. Certain scenes have been interpreted as referring to the 16th-century version of the myth, in particular the shooting of Vucub-Caquix and the restoration of the Twins' dead father (see Maya maize god). This opens up the possibility that the accompanying sections of hieroglyphical text are ancestral to passages from the Popol Vuh. Some stories from the Popol Vuh continued to be told by modern Maya as folk legends; some stories recorded by anthropologists in the 20th century may preserve portions of the ancient tales in greater detail than the Ximénez manuscript.

[edit] Cultural References

The myths and legends contained within Louis L'Amour's novel "The Haunted Mesa" are largely based on the Popol Vuh. The text is used as extensive narration for the first chapter in Werner Herzog's film Fata Morgana (1971)

[edit] Excerpt

Here are the opening lines of the book, in modernized spelling and punctuation (from Sam Colop's edition):

- Are uxe‘ ojer tzij

- waral K‘iche‘ ub‘i‘.

- Waral

- xchiqatz‘ib‘aj wi

- xchiqatikib‘a‘ wi ojer tzij,

- utikarib‘al

- uxe‘nab‘al puch rnojel xb‘an pa

- tinamit K‘iche‘

- ramaq‘ K‘iche‘ winaq.

- "This is the root of the ancient word

- of this place called Quiché.

- Here

- we shall write,

- we shall plant the ancient word,

- the origin

- the beginning of all what has been done in the

- Quiché Nation

- country of the Quiché people."

Here is the opening of the creation story:

- Are utzijoxik wa‘e

- k‘a katz‘ininoq,

- k‘a kachamamoq,

- katz‘inonik,

- k‘a kasilanik,

- k‘a kalolinik,

- katolona puch upa kaj.

- "This is the account of how

- all was in suspense,

- all calm,

- in silence;

- all motionless,

- all pulsating,

- and empty was the expanse of the sky."

[edit] Notes

[edit] References

- Akkeren, Ruud van (2003). "Authors of the Popol Vuh". Ancient Mesoamerica 14: 237–256. ISSN 0956-5361.

- Tedlock, Dennis; (trans.) (1996). Popol Vuh: the Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings. with commentary based on the ancient knowledge of the modern Quiché Maya (revised and expanded edn. ed.). New York: Touchstone Books. ISBN 0-684-81845-0. OCLC 33439111.

[edit] Further reading

| This article includes a list of references or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please improve this article by introducing more precise citations where appropriate. |

- Brasseur de Bourbourg, Charles Étienne (1861). Popol Vuh. Le livre sacré et les mythes de l'antiquité américaine, avec les livres héroïques et historiques des Quichés. Ouvrage original des indigénes de Guatémala, texte quiché et traduction française en regard, accompagnée de notes philologiques et d’un commentaire sur la mythologie et les migrations des peuples anciens de l’Amérique, etc.. Collection de documents dans les langues indigènes, pour servir à l’étude de l’histoire et de la philologie de l’Amérique ancienne, Vol. 1. Paris: Arthus Bertrand. OCLC 7457119. (French) (K'iche')

- Chávez, Adrián Inés (ed.) (1981). Popol Wuj: Poema mito-histórico kí-chè (edición guatemalteca ed.). Quetzaltenango, Guatemala: Centro Editorial Vile. OCLC 69226261.

- Chinchilla Mazariegos, Oswaldo (2003). Los dioses del Popol Vuh en el arte maya clásico = Gods of the Popol Vuh in Classic Maya Art. Guatemala City: Museo Popol Vuh, Universidad Francisco Marroquín. ISBN 99922-775-1-3. OCLC 54755323. (Spanish) (English)

- Christenson, Allen J. (trans.) (2003). Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Maya.. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3839-8.

- Christenson, Allen J. (trans.) (2004). Popol Vuh: Literal Poetic Version: Translation and Transcription.. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3841-1.

- Colop, Sam; (ed.) (1999). Popol Wuj: versión poética K‘iche‘.. Quetzaltenango; Guatemala City: Proyecto de Educación Maya Bilingüe Intercultural; Editorial Cholsamaj. ISBN 99922-53-00-2. OCLC 43379466. (K'iche')

- Edmonson, Munro S.; (ed.) (1971). The Book of Counsel: The Popol-Vuh of the Quiche Maya of Guatemala. Publ. no. 35. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University. OCLC 658606.

- Estrada Monroy, Agustín; (ed.) (1973). Popol Vuh: empiezan las historias del origen de los índios de esta provincia de Guatemala (Facsimile reproduction of Ximénez's manuscript, with notes ed.). Guatemala City: Editorial "José de Piñeda Ibarra". OCLC 1926769.

- Low, Denise (Summer/Fall 1992). "A comparison of the English translations of a Mayan text, the Popol Vuh" (reproduced online). Studies in American Indian Literatures, Series 2 (New York: Association for Study of American Indian Literatures (ASAIL)) 4 (2–3): 15–34. ISSN 0730-3238. OCLC 54533161. http://oncampus.richmond.edu/faculty/ASAIL/SAIL2/42.html. Retrieved on 2008-05-26.

- Recinos, Adrián; (ed.) (1985). Popol Vuh: las antiguas historias del Quiché (6th edn ed.). San Salvador, El Salvador: Editorial Universitaria Centroamericana. OCLC 18385790.

- Sáenz de Santa María, Carmelo, Primera parte del tesoro de las lenguas cakchiquel, quiché y zutuhil, en que las dichal lenguas se trducen a la nuestra, española. Publ. esp. no. 30, Academia de Geografía e Historia de Guatemala; Tipografía Nacional, Guatemala (1985).

- Schultze Jena, Leonhard (trans.) (1944). Popol Vuh: das heilige Buch der Quiché-Indianer von Guatemala, nach einer wiedergefundenen alten Handschrift neu übers. und erlautert von Leonhard Schultze. Stuttgart, Germany: W. Kohlhammer. OCLC 2549190.

- Tedlock, Dennis; (trans.) (1985). Popol Vuh: the Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings. with commentary based on the ancient knowledge of the modern Quiché Maya. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-45241-X. OCLC 11467786.

- Ximénez, Francisco, Primera parte de el tesoro de las lengvas kakchiqvel, qviche y qutuhil Manuscript. Newberry Library, Chicago (ca. 1701).

- Low, Denise (Summer/Fall 1992). "A comparison of the English translations of a Mayan text, the Popol Vuh" (reproduced online). Studies in American Indian Literatures, Series 2 (New York: Association for Study of American Indian Literatures (ASAIL)) 4 (2–3): 15–34. ISSN 0730-3238. OCLC 54533161. http://oncampus.richmond.edu/faculty/ASAIL/SAIL2/42.html. Retrieved on 2008-05-26.

[edit] External links

- English translation of the Popol Vuh from Metareligion.

- Another one.

- And another.

- A facsimile of the earliest preserved manuscript, in Quiché and Spanish, hosted at The Ohio State University Libraries.

- The original Quiché text with line-by-line English translation by Allen J. Christenson

- (French) Le Popol Vuh est la « Bible » des Anciens Mayas-Quichés. Comme d'autres Bibles, il décrit la création, les catastrophes, et la renaissance du Monde.