Context-free grammar

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In formal language theory, a context-free grammar (CFG) is a grammar in which every production rule is of the form

- V → w

where V is a single nonterminal symbol, and w is a string of terminals and/or nonterminals (possibly empty).

Thus, the difference with arbitrary grammars is that the left hand side of a production rule is always a single nonterminal symbol rather than a string of terminal and/or nonterminal symbols. The term "context-free" expresses the fact that nonterminals are rewritten without regard to the context in which they occur.

A formal language is context-free if some context-free grammar generates it. These languages are exactly all languages that can be recognized by a non-deterministic pushdown automaton.

Context-free grammars play a central role in the description and design of programming languages and compilers. They are also used for analyzing the syntax of natural languages.

Contents |

[edit] Background

Since the time of Pāṇini, at least, linguists have described the grammars of languages in terms of their block structure, and described how sentences are recursively built up from smaller phrases, and eventually individual words or word elements.

The context-free grammar (or "phrase-structure grammar" [1] as Chomsky called it) formalism developed by Noam Chomsky[1] in the mid-1950s took the manner in which linguistics had described this grammatical structure and turned it into rigorous mathematics. A context-free grammar provides a simple and precise mechanism for describing the methods by which phrases in some natural language are built from smaller blocks, capturing the "block structure" of sentences in a natural way. Its simplicity makes the formalism amenable to rigorous mathematical study, but it comes at a price: important features of natural language syntax such as agreement and reference cannot be expressed in a natural way, or at all.

Block structure was introduced into computer programming languages by the Algol project, which, as a consequence, also featured a context-free grammar to describe the resulting Algol syntax. This became a standard feature of computer languages, and the notation for grammars used in concrete descriptions of computer languages came to be known as Backus-Naur Form, after two members of the Algol language design committee.

The "block structure" aspect that context-free grammars capture is so fundamental to grammar that the terms syntax and grammar are often identified with context-free grammar rules, especially in computer science. Formal constraints not captured by the grammar are then considered to be part of the "semantics" of the language.

Context-free grammars are simple enough to allow the construction of efficient parsing algorithms which, for a given string, determine whether and how it can be generated from the grammar. An Earley parser is an example of such an algorithm, while the widely used LR and LL parsers are more efficient algorithms that deal only with more restrictive subsets of context-free grammars.

[edit] Formal definitions

A context-free grammar G is a 4-tuple:

where

where

1.  is a finite set of non-terminal characters or variables. They represent different types of phrase or clause in the sentence.

is a finite set of non-terminal characters or variables. They represent different types of phrase or clause in the sentence.

2.  is a finite set of terminals, disjoint with

is a finite set of terminals, disjoint with  , which make up the actual content of the sentence.

, which make up the actual content of the sentence.

3.  is a relation from

is a relation from  to

to  such that

such that  .

.

4.  is the start variable, used to represent the whole sentence (or program). It must be an element of

is the start variable, used to represent the whole sentence (or program). It must be an element of  .

.

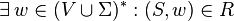

In addition,  is a finite set. The members of

is a finite set. The members of  are called the rules or productions of the grammar. The asterisk represents the Kleene star operation.

are called the rules or productions of the grammar. The asterisk represents the Kleene star operation.

Additional Definition 1

For any strings  , we say

, we say  yields

yields  , written as

, written as  , if

, if  such that

such that  and

and  . Thus,

. Thus,  is the result of applying the rule

is the result of applying the rule  to

to  .

.

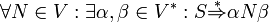

Additional Definition 2

For any  (or

(or  in some textbooks) if

in some textbooks) if  such that

such that

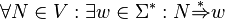

Additional Definition 3

The language of a grammar  is the set

is the set

Additional Definition 4

A language  is said to be a context-free language (CFL) if there exists a CFG,

is said to be a context-free language (CFL) if there exists a CFG,  such that

such that  .

.

Additional Definition 5

A context-free grammar is said to be proper if it has

- no inaccessible symbols:

- no improductive symbols:

- no ε-productions:

- no cycles:

[edit] Examples

[edit] Example 1

- S → a

- S → aS

- S → bS

The terminals here are a and b, while the only non-terminal is S. The language described is all nonempty strings of as and bs that end in a.

This grammar is regular: no rule has more than one nonterminal in its right-hand side, and each of these nonterminals is at the same end of the right-hand side.

Every regular grammar corresponds directly to a nondeterministic finite automaton, so we know that this is a regular language.

It is common to list all right-hand sides for the same left-hand side on the same line, using | to separate them, like this:

- S → a | aS | bS

Technically, this is the same grammar as above.

[edit] Example 2

In a context-free grammar, we can pair up characters the way we do with brackets. The simplest example:

- S → aSb

- S → ab

This grammar generates the language  , which is not regular.

, which is not regular.

The special character ε stands for the empty string. By changing the above grammar to

- S → aSb | ε

we obtain a grammar generating the language  instead. This differs only in that it contains the empty string while the original grammar did not.

instead. This differs only in that it contains the empty string while the original grammar did not.

[edit] Example 3

Here is a context-free grammar for syntactically correct infix algebraic expressions in the variables x, y and z:

- S → x | y | z | S + S | S - S | S * S | S/S | (S)

This grammar can, for example, generate the string "( x + y ) * x - z * y / ( x + x )" as follows: "S" is the initial string. "S - S" is the result of applying the fifth transformation [S → S - S] to the nonterminal S. "S * S - S / S" is the result of applying the sixth transform to the first S and the seventh one to the second S. "( S ) * S - S / ( S )" is the result of applying the final transform to certain of the nonterminals. "( S + S ) * S - S * S / ( S + S )" is the result of the fourth and fifth transforms to certain nonterminals. "( x + y ) * x - z * y / ( x + x )" is the final result, obtained by using the first three transformations to turn the S non terminals into the terminals x, y, and z.

This grammar is ambiguous, meaning that one can generate the same string with more than one parse tree. For example, "x + y * z" might have either the + or the * parsed first; presumably these will produce different results. However, the language being described is not itself ambiguous: a different, unambiguous grammar can be written for it.

[edit] Example 4

A context-free grammar for the language consisting of all strings over {a,b} for which the number of a's and b's are different is

- S → U | V

- U → TaU | TaT

- V → TbV | TbT

- T → aTbT | bTaT | ε

Here, the nonterminal T can generate all strings with the same number of a's as b's, the nonterminal U generates all strings with more a's than b's and the nonterminal V generates all strings with fewer a's than b's.

[edit] Example 5

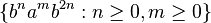

Another example of a non-regular language is  . It is context-free as it can be generated by the following context-free grammar:

. It is context-free as it can be generated by the following context-free grammar:

- S → bSbb | A

- A → aA | ε

[edit] Other examples

Context-free grammars are not limited in application to mathematical ("formal") languages. For example, it has been suggested that a class of Tamil poetry called Venpa is described by a context-free grammar.[2]

[edit] Derivations and syntax trees

There are two common ways to describe how a given string can be derived from the start symbol of a given grammar. The simplest way is to list the consecutive strings of symbols, beginning with the start symbol and ending with the string, and the rules that have been applied. If we introduce a strategy such as "always replace the left-most nonterminal first" then for context-free grammars the list of applied grammar rules is by itself sufficient. This is called the leftmost derivation of a string. For example, if we take the following grammar:

- (1) S → S + S

- (2) S → 1

- (3) S → a

and the string "1 + 1 + a" then a left derivation of this string is the list [ (1), (1), (2), (2), (3) ]. Analogously the rightmost derivation is defined as the list that we get if we always replace the rightmost nonterminal first. In this case this could be the list [ (1), (3), (1), (2), (2)].

The distinction between leftmost derivation and rightmost derivation is important because in most parsers the transformation of the input is defined by giving a piece of code for every grammar rule that is executed whenever the rule is applied. Therefore it is important to know whether the parser determines a leftmost or a rightmost derivation because this determines the order in which the pieces of code will be executed. See for an example LL parsers and LR parsers.

A derivation also imposes in some sense a hierarchical structure on the string that is derived. For example, if the string "1 + 1 + a" is derived according to the leftmost derivation:

- S → S + S (1)

- → S + S + S (1)

- → 1 + S + S (2)

- → 1 + 1 + S (2)

- → 1 + 1 + a (3)

the structure of the string would be:

- { { { 1 }S + { 1 }S }S + { a }S }S

where { ... }S indicates a substring recognized as belonging to S. This hierarchy can also be seen as a tree:

S

/|\

/ | \

/ | \

S '+' S

/|\ |

/ | \ |

S '+' S 'a'

| |

'1' '1'

This tree is called a concrete syntax tree (see also abstract syntax tree) of the string. In this case the presented leftmost and the rightmost derivations define the same syntax tree; however, there is another (leftmost) derivation of the same string

- S → S + S (1)

- → 1 + S (2)

- → 1 + S + S (1)

- → 1 + 1 + S (2)

- → 1 + 1 + a (3)

and this defines the following syntax tree:

S

/|\

/ | \

/ | \

S '+' S

| /|\

| / | \

'1' S '+' S

| |

'1' 'a'

If, for certain strings in the language of the grammar, there is more than one parsing tree, then the grammar is said to be an ambiguous grammar. Such grammars are usually hard to parse because the parser cannot always decide which grammar rule it has to apply. Usually, ambiguity is a feature of the grammar, not the language, and an unambiguous grammar can be found which generates the same context-free language. However, there are certain languages which can only be generated by ambiguous grammars; such languages are called inherently ambiguous.

[edit] Normal forms

Every context-free grammar that does not generate the empty string can be transformed into one in which no rule has the empty string as a product [a rule with ε as a product is called an ε-production]. If it does generate the empty string, it will be necessary to include the rule  , but there need be no other ε-rule. Every context-free grammar with no ε-production has an equivalent grammar in Chomsky normal form or Greibach normal form. "Equivalent" here means that the two grammars generate the same language.

, but there need be no other ε-rule. Every context-free grammar with no ε-production has an equivalent grammar in Chomsky normal form or Greibach normal form. "Equivalent" here means that the two grammars generate the same language.

Because of the especially simple form of production rules in Chomsky Normal Form grammars, this normal form has both theoretical and practical implications. For instance, given a context-free grammar, one can use the Chomsky Normal Form to construct a polynomial-time algorithm which decides whether a given string is in the language represented by that grammar or not (the CYK algorithm).

[edit] Undecidable problems

Some questions that are undecidable for wider classes of grammars become decidable for context-free grammars; e.g. the emptiness problem (whether the grammar generates any terminal strings at all), is undecidable for context-sensitive grammars, but decidable for context-free grammars.

Still, many problems remain undecidable. Examples:

[edit] Universality

Given a CFG, does it generate the language of all strings over the alphabet of terminal symbols used in its rules?

A reduction can be demonstrated to this problem from the well-known undecidable problem of determining whether a Turing machine accepts a particular input (the Halting problem). The reduction uses the concept of a computation history, a string describing an entire computation of a Turing machine. We can construct a CFG that generates all strings that are not accepting computation histories for a particular Turing machine on a particular input, and thus it will accept all strings only if the machine does not accept that input.

[edit] Language equality

Given two CFGs, do they generate the same language?

The undecidability of this problem is a direct consequence of the previous: we cannot even decide whether a CFG is equivalent to the trivial CFG deciding the language of all strings.

[edit] Language inclusion

Given two CFGs, can the first generate all strings that the second can generate?

[edit] Being in a lower level of the Chomsky hierarchy

Given a context-sensitive grammar, does it describe a context-free language? Given a context-free grammar, does it describe a regular language?

Each of these problems is undecidable.

[edit] Extensions

An obvious way to extend the context-free grammar formalism is to allow nonterminals to have arguments, the values of which are passed along within the rules. This allows natural language features such as agreement and reference, and programming language analogs such as the correct use and definition of identifiers, to be expressed in a natural way. E.g. we can now easily express that in English sentences, the subject and verb must agree in number.

In computer science, examples of this approach include affix grammars, attribute grammars, indexed grammars, and Van Wijngaarden two-level grammars.

Similar extensions exist in linguistics.

Another extension is to allow additional symbols to appear at the left hand side of rules, constraining their application. This produces the formalism of context-sensitive grammars.

[edit] Restrictions

Some important subclasses of the context free grammars are:

- Deterministic grammars

- LR(k) grammars, LALR(k) grammars

- LL(l) grammars

These classes are important in parsing: they allow string recognition to proceed deterministically, e.g. without backtracking.

This subclass of the LL(1) grammars is mostly interesting for its theoretical property that language equality of simple grammars is decidable, while language inclusion is not.

These have the property that the terminal symbols are divided into left and right bracket pairs that always match up in rules.

In linear grammars every right hand side of a rule has at most one nonterminal.

This subclass of the linear grammars describes the regular languages, i.e. they correspond to finite automata and regular expressions.

[edit] Linguistic applications

Chomsky initially hoped to overcome the limitations of context-free grammars by adding transformation rules.[1]

Such rules are another standard device in traditional linguistics; e.g. passivization in English. Much of generative grammar has been devoted to finding ways of refining the descriptive mechanisms of phrase-structure grammar and transformation rules such that exactly the kinds of things can be expressed that natural language actually allows. Allowing arbitrary transformations doesn't meet that goal: they are much too powerful (Turing complete).

Chomsky's general position regarding the non-context-freeness of natural language has held up since then[3], although his specific examples regarding the inadequacy of context free grammars (CFGs) in terms of their weak generative capacity were later disproved.[4] Gerald Gazdar and Geoffrey Pullum have argued that despite a few non-context-free constructions in natural language (such as cross-serial dependencies in Swiss German[3] and reduplication in Bambara[5]), the vast majority of forms in natural language are indeed context-free.[4]

[edit] See also

- Context-sensitive grammar

- Formal grammar

- Parsing

- Parsing expression grammar

- Stochastic context-free grammar

- Algorithms for context-free grammar generation

[edit] Notes

- ^ a b c Chomsky, Noam (Sep 1956). "Three models for the description of language". Information Theory, IEEE Transactions 2 (3): 113–124. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/iel5/18/22738/01056813.pdf?isnumber=22738&prod=STD&arnumber=1056813&arnumber=1056813&arSt=+113&ared=+124&arAuthor=+Chomsky%2C+N.. Retrieved on 2007-06-18.

- ^ L, BalaSundaraRaman; Ishwar.S, Sanjeeth Kumar Ravindranath (2003-08-22). "Context Free Grammar for Natural Language Constructs - An implementation for Venpa Class of Tamil Poetry". Proceedings of Tamil Internet, Chennai, 2003: 128-136, International Forum for Information Technology in Tamil. Retrieved on 2006-08-24.

- ^ a b Shieber, Stuart (1985). "Evidence against the context-freeness of natural language". Linguistics and Philosophy 8: 333–343. doi:. http://www.eecs.harvard.edu/~shieber/Biblio/Papers/shieber85.pdf.

- ^ a b Pullum, Geoffrey K.; Gerald Gazdar (1982). "Natural languages and context-free languages". Linguistics and Philosophy 4: 471–504. doi:.

- ^ Culy, Christopher (1985). "The Complexity of the Vocabulary of Bambara". Linguistics and Philosophy 8: 345–351. doi:.

[edit] References

- Chomsky, Noam (Sept. 1956). "Three models for the description of language". Information Theory, IEEE Transactions 2 (3).

[edit] Further reading

- Michael Sipser (1997). Introduction to the Theory of Computation. PWS Publishing. ISBN 0-534-94728-X. Section 2.1: Context-Free Grammars, pp.91–101. Section 4.1.2: Decidable problems concerning context-free languages, pp.156–159. Section 5.1.1: Reductions via computation histories: pp.176–183.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||