CMOS

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) (pronounced "see-moss", IPA: /siːmɔːs, ˈsiːmɒs/), is a major class of integrated circuits. CMOS technology is used in microprocessors, microcontrollers, static RAM, and other digital logic circuits. CMOS technology is also used for a wide variety of analog circuits such as image sensors, data converters, and highly integrated transceivers for many types of communication. Frank Wanlass successfully patented CMOS in 1967 (US Patent 3,356,858).

CMOS was also sometimes referred to as complementary-symmetry metal–oxide–semiconductor (or COS-MOS). The words "complementary-symmetry" refer to the fact that the typical digital design style with CMOS uses complementary and symmetrical pairs of p-type and n-type metal oxide semiconductor field effect transistors (MOSFETs) for logic functions.

Two important characteristics of CMOS devices are high noise immunity and low static power consumption. Significant power is only drawn when the transistors in the CMOS device are switching between on and off states. Consequently, CMOS devices do not produce as much waste heat as other forms of logic, for example transistor-transistor logic (TTL) or NMOS logic, which uses all n-channel devices without p-channel devices. CMOS also allows a high density of logic functions on a chip.

The phrase "metal–oxide–semiconductor" is a reference to the physical structure of certain field-effect transistors, having a metal gate electrode placed on top of an oxide insulator, which in turn is on top of a semiconductor material. Aluminum was once used but now the material is polysilicon. Other metal gates have made a comeback with the advent of high-k dielectric materials in the CMOS process, as announced by IBM and Intel for the 45 nanometer node and beyond [1].

Contents |

[edit] Technical details

"CMOS" refers to both a particular style of digital circuitry design, and the family of processes used to implement that circuitry on integrated circuits (chips). CMOS circuitry dissipates less power when static, and is denser than other implementations having the same functionality. As this advantage has grown and become more important, CMOS processes and variants have come to dominate, so that the vast majority of modern integrated circuit manufacturing is on CMOS processes.[citation needed]

CMOS circuits use a combination of p-type and n-type metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistors (MOSFETs) to implement logic gates and other digital circuits found in computers, telecommunications equipment, and signal processing equipment. Although CMOS logic can be implemented with discrete devices (for instance, in an introductory circuits class), typical commercial CMOS products are integrated circuits composed of millions (or hundreds of millions) of transistors of both types on a rectangular piece of silicon of between 0.1 and 4 square centimeters.[citation needed] These devices are commonly called "chips", although within the industry they are also referred to as "die" (singular) or "dice", "dies", or "die" (plural).

[edit] Composition

The main principle behind CMOS circuits that allows them to implement logic gates is the use of p-type and n-type metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistors to create paths to the output from either the voltage source or ground. When a path to output is created from the voltage source, the circuit is said to be pulled up. On the other hand, the circuit is said to be pulled down when a path to output is created from ground.

[edit] Inversion

CMOS circuits are constructed so that all PMOS transistors must have either an input from the voltage source or from another PMOS transistor. Similarly, all NMOS transistors must have either an input from ground or from another NMOS transistor. The composition of a PMOS transistor creates low resistance when a low voltage is applied to it and high resistance when a high voltage is applied to it. On the other hand, the composition of an NMOS transistor creates high resistance when a low voltage is applied to it and low resistance when a high voltage is applied to it.

The image on the right shows what happens when an input is connected to both a PMOS transistor and an NMOS transistor. When the voltage of input A is low, the NMOS transistor has high resistance so it stops voltage from leaking into ground, while the PMOS transistor has low resistance so it allows the voltage source to transfer voltage through the PMOS transistor to the output. The output would therefore register a high voltage.

On the other hand, when the voltage of input A is high, the PMOS transistor would have high resistance so it would block voltage source from the output, while the NMOS transistor would have low resistance allowing the output to drain to ground. This would result in the output registering a low voltage. In short, the outputs of the PMOS and NMOS transistors are complementary such that when the input is low, the output would be high, and when the input is high, the output would be low. Because of this, the CMOS circuits' output is by default the inversion of the input.

[edit] Duality

An important characteristic of a CMOS circuit is the duality that exists between its PMOS transistors and NMOS transistors. A CMOS circuit is created so that a path would always exist from the output to either the power source or ground. To accomplish this, the set of all paths to the voltage source must be the complement of the set of all paths to ground. This can be easily accomplished by defining one in terms of the NOT of the other. The logic works out through De Morgan's laws such that the PMOS transistors in parallel have corresponding NMOS transistors in series while the PMOS transistors in series have corresponding NMOS transistors in parallel.

[edit] Logic

More complex logic functions such as those involving AND and OR gates require manipulating the paths between gates to represent the logic. When a path consists of two transistors in series, then both transistors must have low resistance for voltage to pass, modeling an AND. When a path consists of two transistors in parallel, then either one or both of the transistors must have low resistance for voltage to pass, modeling an OR.

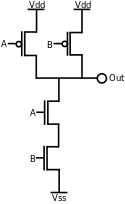

Shown on the right is a circuit diagram of a NAND gate in CMOS logic. If both of the A and B inputs are high, then both the NMOS transistors (bottom half of the diagram) will conduct, neither of the PMOS transistors (top half) will conduct, and a conductive path will be established between the output and Vss (ground), bringing the output low. If either of the A or B inputs is low, one of the NMOS transistors will not conduct, one of the PMOS transistors will, and a conductive path will be established between the output and Vdd (voltage source), bringing the output high.

An advantage of CMOS over NMOS is that both low-to-high and high-to-low output transitions are fast since the pull-up transistors have low resistance when switched on, unlike the load resistors in NMOS logic. In addition, the output signal swings the full voltage between the low and high rails. This strong, more nearly symmetric response also makes CMOS more resistant to noise.

See Logical effort for a method of calculating delay in a CMOS circuit.

[edit] Example: NAND gate in physical layout

This example shows a NAND logic device drawn as a physical representation as it would be manufactured. The physical layout perspective is a "bird's eye view" of a stack of layers. The circuit is constructed on a P-type substrate. The polysilicon, diffusion, and n-well are referred to as "base layers" and are actually inserted into trenches of the P-type substrate. The contacts penetrate an insulating layer between the base layers and the first layer of metal (metal1) making a connection.

The inputs to the NAND (illustrated in green coloring) are in polysilicon. The CMOS transistors (devices) are formed by the intersection of the polysilicon and diffusion: N diffusion for the N device; P diffusion for the P device (illustrated in salmon and yellow coloring respectively). The output ("out") is connected together in metal (illustrated in cyan coloring). Connections between metal and polysilicon or diffusion are made through contacts (illustrated as black squares). The physical layout example matches the NAND logic circuit given in the previous example.

The N device is manufactured on a P-type substrate. The P devices is manufactured in an N-type well (n-well). A P-type substrate "tap" is connected to VSS and an N-type n-well tap is connected to VDD to prevent latchup.

[edit] Complexity measure

For digital standard cell designs, for instance in CMOS, a common technology-independent metric for complexity measure is gate equivalents (GE).

[edit] Power: switching and leakage

CMOS logic dissipates less power than NMOS logic circuits because CMOS dissipates power only when switching ("dynamic power"). On a typical ASIC in a modern 90 nanometer process, switching the output might take 120 picoseconds, and happen once every ten nanoseconds. NMOS logic dissipates power whenever the output is low ("static power"), because there is a current path from Vdd to Vss through the load resistor and the n-type network.

CMOS circuits dissipate power by charging the various load capacitances (mostly gate and wire capacitance, but also drain and some source capacitances) whenever they are switched. The charge moved is the capacitance multiplied by the voltage change. Multiply by the switching frequency on the load capacitances to get the current used, and multiply by voltage again to get the characteristic switching power dissipated by a CMOS device: P = CV2f.

A different form of power consumption became noticeable in the 1990s as wires on chip became narrower and the long wires became more resistive. CMOS gates at the end of those resistive wires see slow input transitions. During the middle of these transitions, both the NMOS and PMOS networks are partially conductive, and current flows directly from Vdd to Vss. The power thus used is called crowbar power. Careful design which avoids weakly driven long skinny wires has ameliorated this effect, and crowbar power is nearly always substantially smaller than switching power.

Both NMOS and PMOS transistors have a gate–source threshold voltage, below which the current through the device drops exponentially. Historically, CMOS designs operated at supply voltages much larger than their threshold voltages (Vdd might have been 5 V, and Vth for both NMOS and PMOS might have been 700 mV). A special type of the CMOS transistor with near zero threshold voltage is the native transistor.

To speed up designs, manufacturers have switched to gate materials that lead to lower voltage thresholds;[citation needed] a modern NMOS transistor with a Vth of 200 mV has a significant subthreshold leakage current. Designs (e.g. desktop processors) which try to optimize their fabrication processes for minimum power dissipation during operation have been lowering Vth so that leakage power begins to approximate switching power. As a result, these devices dissipate considerable power even when not switching. Leakage power reduction using new material and system design is critical to sustaining scaling of CMOS. The industry is contemplating the introduction of high-k dielectrics to combat the increasing gate leakage current by replacing the silicon dioxidea that are the conventional gate dielectrics with materials having a higher dielectric constant. A good overview of leakage and reduction methods are explained in the book Leakage in Nanometer CMOS Technologies ISBN 0-387-25737-3.

[edit] Analog CMOS

Besides digital applications, CMOS technology is also used for analog applications. For example, there are CMOS operational amplifier ICs available in the market. CMOS technology is also widely used for RF applications all the way to microwave frequencies. Indeed, CMOS technology is used for mixed-signal (analog+digital) applications.

[edit] Temperature range

Conventional CMOS devices work over a range of -55 °C to +125 °C. There are indications that silicon CMOS will work down to 40 kelvin.[2]

[edit] See also

- MOSFET

- Gate equivalent (GE)

- Electric and Magic are open-source software often used to lay out CMOS circuits.

[edit] Further reading

- Baker, R. Jacob (2008). CMOS: Circuit Design, Layout, and Simulation, Revised Second Edition. Wiley-IEEE. ISBN 978-0-470-22941-5. http://CMOSedu.com/

- Weste, Neil H. E., Harris, David M. (2005). CMOS VLSI Design: A Circuits and Systems Perspective, Third Edition. Boston: Pearson/Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-321-26977-2. http://CMOSvlsi.com/

- Mead, Carver A. and Conway, Lynn (1980). Introduction to VLSI systems. Boston: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-04358-0.

- Veendrick, Harry J. M. (2008). Nanometer CMOS ICs, from Basics to ASICs. New York: Springer. pp. 770. ISBN 978-1-4020-8332-7.

[edit] References

- ^ Intel 45nm Hi-k Silicon Technology

- ^ Edwards C, "Temperature control", Engineering & Technology Magazine 26 July - 8 August 2008, IET

[edit] External links

- CMOS gate description and interactive illustrations

- LASI is a "general purpose" IC layout CAD tool. It is a free download and can be used as a layout tool for CMOS circuits.