Reductio ad absurdum

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Reductio ad absurdum (Latin for "reduction to the absurd"), also known as an apagogical argument, reductio ad impossibile, or proof by contradiction, is a type of logical argument where one assumes a claim for the sake of argument and derives an absurd or ridiculous outcome, and then concludes that the original claim must have been wrong as it led to an absurd result.

It makes use of the law of non-contradiction — a statement cannot be both true and false. In some cases it may also make use of the law of excluded middle — a statement must be either true or false. The phrase is traceable back to the Greek ἡ εἰς ἄτοπον ἀπαγωγή (hē eis átopon apagōgḗ), meaning "reduction to the absurd", often used by Aristotle.

In mathematics and formal logic, this refers specifically to an argument where a contradiction is derived from some assumption (thus showing that the assumption must be false). However, Reductio ad absurdum is also often used to describe any argument where a conclusion is derived in the belief that everyone (or at least those being argued against) will accept that it is false or absurd. This is a comparatively weak form of reductio, as the decision to reject the premise requires that the conclusion is accepted as being absurd. Although a formal contradiction is by definition absurd (unacceptable), a weak reductio ad absurdum argument can be rejected simply by accepting the purportedly absurd conclusion. Such arguments also risk degenerating into strawman arguments, an informal fallacy caused when an argument or theory is twisted by the opposing side to appear ridiculous.

Contents |

[edit] Explanation

In formal logic, reductio ad absurdum is used when a formal contradiction can be derived from a premise, allowing one to conclude that the premise is false. If a contradiction is derived from a set of premises, this shows that at least one of the premises is false; if there are several, other means must be used to determine which ones. Mathematical proofs are sometimes constructed using reductio ad absurdum, by first assuming the opposite of the theorem the presenter wishes to prove, then reasoning logically from that assumption until presented with a contradiction. Upon reaching the contradiction, the assumption is disproved and therefore its opposite, due to the law of excluded middle, must be true.

There is a fairly common misconception that reductio ad absurdum simply denotes "a silly argument" and is itself a formal fallacy. However, this is not correct; a properly constructed reductio constitutes a correct argument. When reductio ad absurdum is in error, it is because of a fallacy in the reasoning used to arrive at the contradiction, not the act of reduction itself.

[edit] Examples

A classic reductio proof from Greek mathematics is the proof that the square root of 2 is irrational. If it were rational, it could be expressed as a fraction a/b in lowest terms, where a and b are integers, at least one of which is odd. But if a/b = √2, then a2 = 2b2. That implies a2 is even. Because the square of an odd number is odd, that in turn implies that a is even. This means that b must be odd because a/b is in lowest terms.

On the other hand, if a is even, then a2 is a multiple of 4. If a2 is a multiple of 4 and a2 = 2b2, then 2b2 is a multiple of 4, and therefore b2 is even, and so is b.

So b is odd and even, a contradiction. Therefore the initial assumption—that √2 can be expressed as a fraction—must be false.

[edit] Cubing-the-cube puzzle

A more recent use of a reductio argument is the proof that a cube cannot be cut into a finite number of smaller cubes with no two the same size. Consider the smallest cube on the bottom face; on each of its four sides, either a neighbouring cube or the border of the main cube is rising above it. This means that any larger cube will not fit on top of it (the "footprint" of such a cube is too large). Since different cubes aren't permitted to have the same sizes, only smaller cubes can be placed directly on top of it. But then the smallest of these would likewise be surrounded by larger cubes, so could only have smaller cubes directly on top of it... and so on, in an infinite regress, requiring an infinite number of cubes, which violates our conditions. (This gives rise to a proof by induction that the cubing-the-cube puzzle is also unsolvable in dimensions higher than three.)

[edit] In mathematics

Say we wish to disprove proposition p. The procedure is to show that assuming p leads to a logical contradiction. Thus, according to the law of non-contradiction, p must be false.

Say instead we wish to prove proposition p. We can proceed by assuming "not p" (i.e. that p is false), and show that it leads to a logical contradiction. Thus, according to the law of non-contradiction, "not p" must be false, and so, according to the law of the excluded middle, p is true.

In symbols:

To disprove p: one uses the tautology (p → (R ∧ ¬R)) → ¬p, where R is any proposition and the ∧ symbol is taken to mean "and". Assuming p, one proves R and ¬R, and concludes from this that p → (R ∧ ¬R). This and the tautology together imply ¬p.

To prove p: one uses the tautology (¬p → (R ∧ ¬R)) → p where R is any proposition. Assuming ¬p, one proves R and ¬R, and concludes from this that ¬p → (R ∧ ¬R). This and the tautology together imply p.

For a simple example of the first kind, consider the proposition, ¬p: "there is no smallest rational number greater than 0". In a reductio ad absurdum argument, we would start by assuming the opposite, p: that there is a smallest rational number, say, r0.

Now let  . Then x is a rational number, and it's greater than 0; and x is smaller than r0. (In the above symbolic argument, "x is the smallest rational number" would be R and "r0 (which is different from x) is the smallest rational number" would be ¬R.) But that contradicts our initial assumption, p, that r0 was the smallest rational number. So we can conclude that the original proposition, ¬p, must be true — "there is no smallest rational number greater than 0".

. Then x is a rational number, and it's greater than 0; and x is smaller than r0. (In the above symbolic argument, "x is the smallest rational number" would be R and "r0 (which is different from x) is the smallest rational number" would be ¬R.) But that contradicts our initial assumption, p, that r0 was the smallest rational number. So we can conclude that the original proposition, ¬p, must be true — "there is no smallest rational number greater than 0".

[Note: the choice of which statement is R and which is ¬R is arbitrary.]

It is common to use this first type of argument with propositions such as the one above, concerning the non-existence of some mathematical object. One assumes that such an object exists, and then proves that this would lead to a contradiction; thus, such an object does not exist. For other examples, see proof that the square root of 2 is not rational and Cantor's diagonal argument.

On the other hand, it is also common to use arguments of the second type concerning the existence of some mathematical object. One assumes that the object doesn't exist, and then proves that this would lead to a contradiction; thus, such an object must exist. Although it is quite freely used in mathematical proofs, not every school of mathematical thought accepts this kind of argument as universally valid. See further Nonconstructive proof.

[edit] In mathematical logic

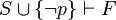

In mathematical logic, the reductio ad absurdum is represented as:

- if

- then

or

- if

- then

In the above, p is the proposition we wish to prove or disprove; and S is a set of statements which are given as true — these could be, for example, the axioms of the theory we are working in, or earlier theorems we can build upon. We consider p, or the negation of p, in addition to S; if this leads to a logical contradiction F, then we can conclude that the statements in S lead to the negation of p, or p itself, respectively.

Note that the set-theoretic union, in some contexts closely related to logical disjunction (or), is used here for sets of statements in such a way that it is more related to logical conjunction (and).

[edit] Humour

The often humorous outcome of extending the simplification of a flawed statement to ridiculous proportions with the aim of criticising the result is frequently utilised in forms of humour. In fiction, seemingly simple and innocuous actions that are extended beyond reasonable circumstance to chaotic outcomes, typically by use of stereotype and literal interpretation, can also be categorised as reductio ad absurdum[1]. See farce.

Example:

- Prove: All positive integers are interesting.

- Proof: Assume there exists an uninteresting positive integer. Then there must be a smallest uninteresting positive integer. However, being the smallest uninteresting positive integer is in itself interesting. Thus you have a contradiction and all positive integers are interesting.

[edit] Notation

Proofs by reductio ad absurdum often end "Contradiction!" or "What a contradiction!" Isaac Barrow and Baermann used the notation Q.E.A., for "quod est absurdum" ("which is absurd"), along the lines of Q.E.D., but this notation is rarely used today[2]. A graphical symbol sometimes used for contradictions is a downwards zigzag arrow "lightning" symbol (U+21AF: ↯), for example in Davey and Priestley[3]. Others sometimes used include a pair of opposing arrows (as  or

or  ), struck-out arrows (

), struck-out arrows ( ), a stylized form of hash (such as U+2A33: ⨳), or the "reference mark" (U+203B: ※).[4][5] The "up tack" symbol (U+22A5: ⊥) used by philosophers and logicians (see contradiction) also appears, but is often avoided due to its usage for orthogonality.

), a stylized form of hash (such as U+2A33: ⨳), or the "reference mark" (U+203B: ※).[4][5] The "up tack" symbol (U+22A5: ⊥) used by philosophers and logicians (see contradiction) also appears, but is often avoided due to its usage for orthogonality.

[edit] Quotations

In the words of G. H. Hardy (A Mathematician's Apology), "Reductio ad absurdum, which Euclid loved so much, is one of a mathematician's finest weapons. It is a far finer gambit than any chess gambit: a chess player may offer the sacrifice of a pawn or even a piece, but a mathematician offers the game."

In the first paragraph of the Quentin Section (Part 2: June Second, 1910) of William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury, Quentin's father, Mr. Compson, gives his son a watch that has been in the family for many generations. His father explains, "It [the watch] was Grandfather's and when Father gave it to me he said I give you the mausoleum of all hope and desire; it's rather excruciating-ly apt that you will use it to gain the reducto absurdum of all human experience which can fit your individual needs no better that it fitted his or his father's". This example represents a corruption of the Latin phrase Reductio ad absurdum.

[edit] References

- ^ N.A. Walker, What's So Funny: Humor in American Culture, Rowman & Littlefield, 1998.

- ^ Hartshorne on QED and related

- ^ B. Davey and H.A. Prisetley, Introduction to lattices and order, Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- ^ The Comprehensive LaTeX Symbol List, pg. 20. http://www.ctan.org/tex-archive/info/symbols/comprehensive/symbols-a4.pdf

- ^ Gary Hardegree, Introduction to Modal Logic, Chapter 2, pg. II-2. http://people.umass.edu/gmhwww/511/pdf/c02.pdf

[edit] Further reading

- J. Franklin and A. Daoud, Proof in Mathematics: An Introduction, Quakers Hill Press, 1996, ch. 6