Memento mori

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Memento mori is a Latin phrase meaning "Be mindful of death" and may be translated as "Remember that you are mortal," "Remember you will die," "Remember that you must die," or "Remember your death". It names a genre of artistic creations that vary widely from one another, but which all share the same purpose, which is to remind people of their own mortality.

Contents |

[edit] Ancient times

In ancient Rome, the phrase is said to have been used on the occasions when a Roman general was parading through the streets of Rome during the victory celebration known as a triumph. Standing behind the victorious general was a slave, and he had the task of reminding the general that, though he was up on the peak today, tomorrow was another day. The servant did this by telling the general that he should remember that he was mortal: "Memento mori." It is also possible that the servant said, rather, "Respice post te! Hominem te esse memento!": "Look behind you! Remember that you are but a man!", as noted in Tertullian in his Apologeticus.[1] Another phrase used in such a setting is Sic transit gloria mundi.

The concept, in the art of classical antiquity, was more frequently embodied in the phrase carpe diem, or "seize the day," a phrase most well-known from Horace's ode to Leuconoe[2]. This carries echoes of the admonishment to "eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die", the language of which originates in Isaiah 22:13: "But look! you feast and celebrate, you slaughter oxen and butcher sheep, You eat meat and drink wine: 'Eat and drink, for tomorrow we die!'"[3] The memento mori and carpe diem appear elsewhere in Roman literature most notably in Horace's Odes (e.g. Odes 1.4 to Lucius Sestius, 2.3 to Quintus Dellius, 2.14 to Postumus, and 4.7 to Torquatus). This theme is repeated in the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, stanza XXXV: '..."While you live, / Drink!—for, once dead, you never shall return.' and the popular theme of "Timor mortis conturbat me, quilla inferno nulla est redemptio": "the fear of death torments me because in Hell there is no redemption".

[edit] Postclassical Europe

The thought came into its own with Christianity, whose strong emphasis on Divine Judgment, Heaven, Hell, and the salvation of the soul brought death to the forefront of consciousness. Most memento mori works are products of Christian art, although there are equivalents in Buddhist art. In the Christian context, the memento mori acquires a moralizing purpose quite opposed to the Nunc est bibendum theme of Classical antiquity. To the Christian, the prospect of death serves to emphasize the emptiness and fleetingness of earthly pleasures, luxuries, and achievements, and thus also as an invitation to focus one's thoughts on the prospect of the afterlife. A Biblical injunction often associated with the memento mori in this context is In omnibus operibus tuis memorare novissima tua, et in aeternum non peccabis (the Vulgate's Latin rendering of Ecclesiasticus 7:40, "in all thy works be mindful of thy last end and thou wilt never sin.") This finds ritual expression in the Catholic rites of Ash Wednesday when ashes are placed upon the worshipers' heads with the words "Remember Man that you are dust and unto dust you shall return."

The most obvious places to look for memento mori meditations are in funereal art and architecture. Perhaps the most striking to contemporary minds is the transi, or cadaver tomb, a tomb which depicts the decayed corpse of the deceased. This became a fashion in the tombs of the wealthy in the fifteenth century, and surviving examples still create a stark reminder of the vanity of earthly riches. The famous danse macabre, with its dancing depiction of the Grim Reaper carrying off rich and poor alike, is another well known example of the memento mori theme. This and similar depictions of Death decorated many European churches. Later, Puritan tombstones in the colonial United States frequently depicted winged skulls, skeletons, or angels snuffing out candles. See the themes associated with skull imagery.

Timepieces were formerly an apt reminder that your time on earth grows shorter with each passing minute. Public clocks would be decorated with mottos such as ultima forsan ("perhaps the last" [hour]) or vulnerant omnes, ultima necat ("they all wound, and the last kills"). Even today, clocks often carry the motto tempus fugit, "time flies." Old striking clocks often sported automata who would appear and strike the hour; some of the celebrated automaton clocks from Augsburg, Germany had Death striking the hour. The several computerized "death clocks" revive this old idea. Private people carried smaller reminders of their own mortality. Mary Queen of Scots owned a large watch carved in the form of a silver skull, embellished with the lines of Horace.

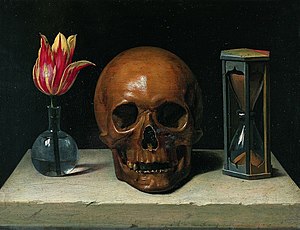

The artistic genre of still life was formerly called Vanitas, Latin for "vanity", because it was thought appropriate for each such painting to include some kind of symbol of mortality in each picture; these could be obvious ones like skulls, or more subtle ones, like a flower losing its petals. See the themes associated with the image of the skull.

After the invention of photography, many people had photographs taken of recently dead family members; given the technical limitations of daguerreotype photography, this was one way to get the portrait subject to sit still.

Memento mori was also an important literary theme. Well known literary meditations on death in English prose include Sir Thomas Browne's Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial and Jeremy Taylor's Holy Living and Holy Dying. These works were part of a Jacobean cult of melancholia that marked the end of the Elizabethan era. In the late eighteenth century, literary elegies were a common genre; Thomas Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard and Edward Young's Night Thoughts were typical members of the genre.

Apart from the genre of requiem and funeral music there is also a rich tradition of memento mori in the Early Music of Europe. Especially those facing the ever present death during the recurring bubonic plague pandemias from the 1340s onward (see Black Death) tried to toughen themselves by anticipating the inevitable in chants, from the simple Geisslerlieder of the Flagellant movement to the more refined cloistral or courtly songs. The lyrics often looked at life as a necessary and god-given vale of tears with death as a ransom and reminded people to lead sinless lives to stand a chance at Judgement Day. Two stanzas typical of memento mori in mediaeval music are from the virelai ad mortem festinamus of the Catalan Llibre Vermell de Montserrat from 1399:

- Vita brevis breviter in brevi finietur,

- Mors venit velociter quae neminem veretur,

- Omnia mors perimit et nulli miseretur.

- Ad mortem festinamus peccare desistamus.

- Life is short, and shortly it will end;

- Death comes quickly and respects no one,

- Death destroys everything and takes pity on no one.

- To death we are hastening, let us refrain from sinning.

- Ni conversus fueris et sicut puer factus

- Et vitam mutaveris in meliores actus,

- Intrare non poteris regnum Dei beatus.

- Ad mortem festinamus peccare desistamus.

- If you do not turn back and become like a child,

- And change your life for the better,

- You will not be able to enter, blessed, the Kingdom of God.

- To death we are hastening, let us refrain from sinning.

Much memento mori art is associated with the Mexican festival, Day of the Dead, including even skull-shaped candies, and bread loaves adorned with bread "bones". It was also famously expressed in the works of the Mexican engraver José Guadalupe Posada, in which various walks of life are depicted as skeletons.

The motto of the French village of Èze is the phrase: "Moriendo Renascor" (meaning "In death I am Reborn") and its emblem is a phoenix perched on a bone.

[edit] Puritan America

Colonial American art saw a large amount of "memento mori" images in their art because of their puritan influence. The Puritan community in 17th century America looked down upon art because they believed it drew the faithful away from God, and if away from God, then it could only lead to the devil. However, portraits were considered historical records, and as such they were allowed. Thomas Smith, a 17th century Puritan, fought in many naval battles, and also painted. In his painting Self-Portrait we see a typical puritan "memento mori" with a skull, suggesting his imminent death.

The poem under the skull is a common puritanical poem which emphasizes Smith's acceptance of death:

Why why should I the World be minding,Therein a World of Evils Finding. Then Farwell World: Farwell thy jarres, thy Joies thy Toies thy Wiles thy Warrs. Truth Sounds Retreat: I am not sorye. The Eternall Drawes to him my heart, By Faith (which can thy Force Subvert) To Crowne me (after Grace) with Glory.

[edit] See also

- Afterlife

- Ars moriendi

- Danse Macabre

- Death (personification)

- Death poem

- Elegy

- Epitaph

- Et in Arcadia ego

- List of Latin Phrases

- Lament

- Macabre

- Post-mortem photography

- Skull symbolism

- Symbols of death

- Terror management theory

- Ubi sunt

- Vanitas

[edit] References

| This article does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2008) |

- ^ Apologeticus, Chapter 33.

- ^ Odes 1.11.8

- ^ New American Bible translation

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Memento mori |

- Isaiah 22

- Apologeticus

- Memento Mori Gallery

- Mike Shinoda Memento Mori

- http://www.danemunro.com/arsmoriendi.html, an article on memento mori and ars moriendi appearing in the publication of Dane Munro, 'Memento Mori, a companion to the most beautiful floor in the world' (Malta, 2005) ISBN9993290115, 2 vols. The ars moriendi eulogies of the Knights of the Order of St John.