Cantor's diagonal argument

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Cantor's diagonal argument, also called the diagonalisation argument, the diagonal slash argument or the diagonal method, was published in 1891 by Georg Cantor as a proof that there are infinite sets which cannot be put into one-to-one correspondence with the infinite set of natural numbers. Such sets are now known as uncountable sets, and the size of infinite sets is now treated by the theory of cardinal numbers which Cantor began.

The diagonal argument was not Cantor's first proof of the uncountability of the real numbers; it was actually published much later than his first proof, which appeared in 1874. However, it demonstrates a powerful and general technique that has since been used in a wide range of proofs, also known as diagonal arguments by analogy with the argument used in this proof. The most famous examples are perhaps Russell's paradox, the first of Gödel's incompleteness theorems, and Turing's answer to the Entscheidungsproblem.

Contents |

[edit] An uncountable set

Cantor's original proof considers an infinite sequence of the form (x1, x2, x3, ...) where each element xi is either 0 or 1.

Consider any infinite listing of some of these sequences. We might have for instance:

- s1 = (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...)

- s2 = (1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, ...)

- s3 = (0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, ...)

- s4 = (1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, ...)

- s5 = (1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, ...)

- s6 = (0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, ...)

- s7 = (1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, ...)

- ...

And in general we shall write

- sn = (sn,1, sn,2, sn,3, sn,4, ...)

that is to say, sn,m is the mth element of the nth sequence on the list.

It is possible to build a sequence of elements s0 in such a way that its first element is different from the first element of the first sequence in the list, its second element is different from the second element of the second sequence in the list, and, in general, its nth element is different from the nth element of the nth sequence in the list. That is to say, s0,m will be 0 if sm,m is 1, and s0,m will be 1 if sm,m is 0. For instance:

- s1 = (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...)

- s2 = (1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, ...)

- s3 = (0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, ...)

- s4 = (1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, ...)

- s5 = (1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, ...)

- s6 = (0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, ...)

- s7 = (1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, ...)

- ...

- s0 = (1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, ...)

(The elements s1,1, s2,2, s3,3, and so on, are here highlighted, showing the origin of the name "diagonal argument". Note that the highlighted elements in s0 are in every case different from the highlighted elements in the table above it.)

Therefore it may be seen that this new sequence s0 is distinct from all the sequences in the list. This follows from the fact that if it were identical to, say, the 10th sequence in the list, then we would have s0,10 = s10,10. In general, if it appeared as the nth sequence on the list, we would have s0,n = sn,n, which, due to the construction of s0, is impossible.

From this it follows that the set T, consisting of all infinite sequences of zeros and ones, cannot be put into a list s1, s2, s3, ... Otherwise, it would be possible by the above process to construct a sequence s0 which would both be in T (because it is a sequence of 0s and 1s which is by the definition of T in T) and at the same time not in T (because we can deliberately construct it not to be in the list). T, containing all such sequences, must contain s0, which is just such a sequence. But since s0 does not appear anywhere on the list, T cannot contain s0.

Therefore T cannot be placed in one-to-one correspondence with the natural numbers. In other words, it is uncountable.

The interpretation of Cantor's result will depend upon one's view of mathematics. To constructivists, the argument shows no more than that there is no bijection between the natural numbers and T. It does not rule out the possibility that the latter are subcountable. In the context of classical mathematics, this is impossible, and the diagonal argument establishes that, although both sets are infinite, there are actually more infinite sequences of ones and zeros than there are natural numbers.

[edit] Real numbers

The uncountability of the real numbers was already established by Cantor's first uncountability proof, but it also follows from this result.

Naively, one might consider infinite binary strings (sequences of 0s and 1s) as being binary expansions of a real number (between 0 and 1). However, non-uniqueness of decimal expansions (and likewise binary expansions) means that this argument does not work: two different binary strings may correspond to the same real number. Thus the new sequence produced by diagonalisation might equal one of the listed sequences as real numbers.

This technicality can be finessed: one can use ternary expansions of reals, never ending in  (instead ending in

(instead ending in  ), and only using 0 or 1 (not 2) in constructing the new sequence that isn't in the list.

), and only using 0 or 1 (not 2) in constructing the new sequence that isn't in the list.

More abstractly, the set T and the real numbers can be placed into one-to-one correspondence, and we say that they both have the cardinality of the continuum. As T is uncountable, it follows that the real numbers must also be uncountable. One way to show that they have the same cardinality is to produce injections  and

and  and applying the Cantor–Bernstein–Schroeder theorem.

and applying the Cantor–Bernstein–Schroeder theorem.

Further discussion in the cardinality of the continuum.

[edit] General sets

A generalized form of the diagonal argument was used by Cantor to prove Cantor's theorem: for every set S the power set of S, i.e., the set of all subsets of S (here written as P(S)), is larger than S itself. This proof proceeds as follows:

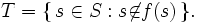

Let f be any function from S to P(S). It suffices to prove f cannot be surjective. That means that some member of P(S), i.e., some subset of S, is not in the image of f. Such a set is

T is not in the image of f: for all  , either s is in T or not, and in both cases,

, either s is in T or not, and in both cases,  .

.

If  , then by definition of T,

, then by definition of T,  , so

, so  since

since  but

but  .

.

If  , then by definition of T,

, then by definition of T,  , so

, so  , since

, since  but

but  .

.

For a more complete account of this proof, see Cantor's theorem.

[edit] Consequences

This result implies that the notion of the set of all sets is an inconsistent notion. If S were the set of all sets then P(S) would at the same time be bigger than S and a subset of S.

Russell's Paradox has shown us that naive set theory, based on an unrestricted comprehension scheme, is contradictory. Note that there is a similarity between the construction of T and the set in Russell's paradox. Therefore, depending on how we modify the axiom scheme of comprehension in order to avoid Russell's paradox, arguments such as the non-existence of a set of all sets may or may not remain valid.

The diagonal argument shows that the set of real numbers is "bigger" than the set of integers. Therefore, we can ask if there is a set whose cardinality is "between" that of the integers and that of the reals. This question leads to the famous continuum hypothesis. Similarly, the question of whether there exists a set whose cardinality is between |S| and |P(S)| for some infinite S leads to the generalized continuum hypothesis.

Analogues of the diagonal argument are widely used in mathematics to prove the existence or nonexistence of certain objects. For example, the conventional proof of the unsolvability of the halting problem is essentially a diagonal argument. Also, diagonalization was originally used to show the existence of arbitrarily hard complexity classes and played a key role in early attempts to prove P does not equal NP. In 2008, diagonalization was used to "slam the door" on Laplace's demon.[1]

[edit] Version for Quine's New Foundations

The above proof fails for W. V. Quine's "New Foundations" set theory (NF). In NF, the naive axiom scheme of comprehension is modified to avoid the paradoxes by introducing a kind of "local" type theory. In this axiom scheme,  is not a set — i.e., does not satisfy the axiom scheme. On the other hand, we might try to create a modified diagonal argument by noticing that

is not a set — i.e., does not satisfy the axiom scheme. On the other hand, we might try to create a modified diagonal argument by noticing that  is a set in NF. In which case, if P1(S) is the set of one-element subsets of S and f is a proposed bijection from P1(S) to P(S), one is able to use reductio to prove that |P1(S)| < |P(S)|.

is a set in NF. In which case, if P1(S) is the set of one-element subsets of S and f is a proposed bijection from P1(S) to P(S), one is able to use reductio to prove that |P1(S)| < |P(S)|.

The proof follows by the fact that if f were indeed a map onto P(S)), then we could find  coincides with the modified diagonal set, above. We would conclude that if

coincides with the modified diagonal set, above. We would conclude that if  , then

, then  and vice-versa.

and vice-versa.

It is not possible to put P1(S) in a one-to-one relation with S, as the two have different types, and so any function so defined would violate the typing rules for the comprehension scheme.

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ P. Binder, "Theories of almost everything", Nature, 455 (2008), 884-885.