Kraftwerk

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. Please improve this article if you can. (January 2009) |

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2009) |

| Kraftwerk | |

|---|---|

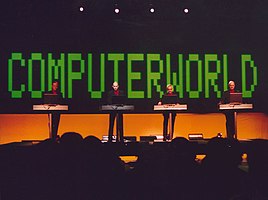

Kraftwerk live in Stockholm in 2004

|

|

| Background information | |

| Origin | Düsseldorf, Germany |

| Genre(s) | Electronic Synthpop Krautrock (early period) |

| Years active | 1970–present |

| Label(s) | Kling Klang EMI Astralwerks Elektra Warner Bros. Capitol Vertigo Philips |

| Associated acts | Organisation Neu! Karl Bartos Wolfgang Flür |

| Website | Official Web Site |

| Members | |

| Ralf Hütter Fritz Hilpert Henning Schmitz Stefan Pfaffe |

|

| Former members | |

| Karl Bartos Klaus Dinger Wolfgang Flür Andreas Hohmann Klaus Röder Michael Rother Florian Schneider |

|

Kraftwerk (pronounced [ˈkʁaftvɛɐk], German for "power plant" or "power station") is an influential electronic music band from Düsseldorf, Germany. The signature Kraftwerk sound combines driving, repetitive rhythms with catchy melodies, mainly following a Western classical style of harmony, with a minimalistic and strictly electronic instrumentation. The group's simplified lyrics are at times sung through a vocoder or generated by computer-speech software. In the early to late 1970s and the early 1980s, Kraftwerk's distinctive sound was revolutionary for its time, and it has had a lasting impact across many genres of modern popular music.[1][2][3][4][5]

Contents |

[edit] Biography

[edit] Band formation

Kraftwerk were formed in 1970 by Florian Schneider (flutes, synthesizers, electro-violin) and Ralf Hütter (electronic organ, synthesizers). The two had met as students at the Düsseldorf Conservatory in the late 1960s, participating in the German experimental music scene of the time, which the British music press dubbed "Krautrock".[6]

The duo had originally performed together in a quintet known as Organisation.[7] This ensemble released one album, titled Tone Float (issued on RCA Records in the UK)[8] but the unit split shortly thereafter. Early Kraftwerk line-ups from 1970–1974 fluctuated, as Hütter and Schneider worked with around a half-dozen other musicians over the course of recording three albums and sporadic live appearances; most notably guitarist Michael Rother and drummer Klaus Dinger, who left to form Neu!.[9]

The input, expertise, and influence of producer/engineer Konrad "Conny" Plank was highly significant in the early years of Kraftwerk and Plank also worked with many of the other leading German electronic acts of the period, including members of Can, Neu!, Cluster and Harmonia. As a result of his work with Kraftwerk, Plank's studio near Köln became one of the most sought-after studios in the late 1970s. Plank co-produced the first four Kraftwerk albums.[10]

[edit] 1974 - 1975

The release of Autobahn, in 1974[11] saw the band moving away from the sound of their earlier albums. They invested in newer technology such as a Minimoog, helping give them a newer, disciplined sound. [12] Autobahn would also be the last album that Conny Plank would engineer. [13] After the commercial success of Autobahn the band invested money into updating their studio. This meant they no longer had to rely on outside producers.[14] At this time the painter and graphic artist Emil Schult became a regular collaborator with the band, working alongside the band.[15] Schult designed artwork in addition to later writing lyrics and accompanying the group on tour.[16]

The now regarded classic line-up of Kraftwerk was formed in 1975 for Autobahn tour. During this time, the band were presented as a quartet, with Hütter and Schneider joined by Wolfgang Flür and Karl Bartos, hired as electronic percussionists.[17] This quartet would be the band's public persona for its renowned output of the latter 1970s and early 1980s. Flür had already joined the band in 1973, in preparation for a television appearance to promote Kraftwerk's third album.[18]

After the 1975 Autobahn tour Kraftwerk began work on a follow up album, Radio-Activity. [19] After further investment of new equipment, their Kling Klang studio was now a fully working recording studio. [20] It was decided that the new album would have a central theme. This theme came from their interest in radio communication, which had become enhanced on their last tour of America. [21] While Emil Schult began working on artwork and lyrics for the new album, the band began to work on the music. [22] Radio-Activity didn't live up to it's predecessor and was less successful in the UK and American markets. But it did open up the European market for the band, gaining them a gold disc in France.[23] Kraftwerk produced some promotional videos and performed several European live dates to promote the album. [24] With the release of Autobahn and Radio-Activity Kraftwerk had left behind their avant-garde experimentations and had moved forward toward electronic pop tunes. [25]

[edit] 1976 - 1982

In 1976 Kraftwerk began recording Trans-Europe Express at Kling Klang studio.[26] At this time a technical innovation was happening at Kling Klang studio. Hütter and Schneider had commisioned Matten & Wiechers, a Bonn based synthesiser studio, to design and build a sixteen track music sequencer.[27] The music sequencer controlled the band’s Minimoog creating the albums rhythmic sound.[28] Trans-Europe Express was mixed at the Record Plant Studios in Los Angeles and found the location to have a stimulating atmosphere. [29] It was around this time that Hütter and Schneider met David Bowie at Kling Klang studio. A music collaboration was also mentioned in an interview with Hütter, but it never materialised. [30] Kraftwerk had previously been offered a support slot on Bowie's Station to Station tour, but they turned it down.[31] The release of Trans-Europe Express was marked with an extravagant train journey used as a press conference by EMI France.[32] The album was released in 1977.[33] Trans-Europe Express marked the band's complete transformation into an electronic pop band.[34]

In May 1978 Kraftwerk released The Man-Machine.[35] The album was recorded at Kling Klang. During the recording of the album the band would sit behind the Kling Klang mixing console and let the sequencers and studio equipment play melodies. Florian Schneider would then stand up and move toward a sequencer and launch another musical sequence. This was Kraftwerk’s style of “jamming”. This process would be repeated until the tracks were built up into songs.[36] Due to the complexity of the recording the album was mixed at Studio Rudas in Düsseldorf. [37] Two mixing engineers Joschko Rudas and Leanard Jackson, from LA, were employed to mix the album.[38] The cover to the new album was produced in black, white and red, the artwork was inspired by Russian artist El Lissitzky.[39] The image of the band on the front cover was photographed by Gunther Frohling. This showed the band dressed in red shirts and black ties.[40] Following the release of The Man-Machine Kraftwerk would not release an album for another three years. [41]

In May 1981 Kraftwerk released the album Computer World on EMI records. [42] The album was recorded at Kling Klang Studio between 1978 and 1981. [43] A lot of this time was spent modifying the Kling Klang Studio so the band could take it on tour with them. [44] Some of the electronic vocals on Computer World were created using a Texas Instruments Language Translator[45] "Computer Love" was released as a single from the album backed with an earlier Kraftwerk track titled "The Model". [46] Radio DJs were more interested in the b-side so the single was repackaged by EMI and re-released with "The Model" as the a-side. [47] The single reached the number one position in the UK making "The Model" Kraftwerk’s most successful record in the UK. [48]

[edit] 1983 - 1989

In 1983 EMI released the single Tour de France.[49] The original 12” release was delayed by the record company until they had further news of a new album.[50] In the end EMI released the 12” with no news of a new album.[51] It was at this time that the band took up cycling.[52] Ralf Hütter had been looking for a new form of exercise.[53] Kraftwerk decided to take on the new image of the bicycle. Tour de France included sounds that followed this theme including bicycle chains, gear mechanisms and even the breathing of the cyclist.[54] At the time of the single’s release Ralf Hütter tried to persuade the rest of the band that they should record a whole album based around cycling.[55] The other members of the band were not so convinced. The theme was left to the single alone.[56] The most familiar version of the song was recorded using French vocals. These vocals were recorded on the Kling Klang Studio stairs to create the right atmosphere.[57] During the recording of Tour de France Ralf Hütter was involved in a serious cycling accident.[58] He suffered serious head injuries and was left in a coma for a few days.[59] Tour de France featured in the 1983 film Breakdance showing the influence that Kraftwerk had on black American dance music.[60] Following his recovery Ralf Hütter threw himself back into his obsession with cycling.[61] During 1983 Wolfgang Flür was beginning to spend less time in the studio. Since the band began using sequencers his role as a drummer was becoming less frequent.[62] He preferred to spend his time traveling with his girlfriend.[63] Flür was also experiencing artistic difficulties with the band.[64] After his final work on the 1986 album Electric Café he hardly returned to the Kling Klang Studio.[65]

[edit] 1990 - present

During the early nineties Kraftwerk's line up changed several times. In 1990 Fritz Hilpert replaced Wolfgang Flür on electronic percussion and sound effects,[66] and in early 1991 Fernando Abrantes replaced Karl Bartos on electronic percussion and sound effects. Later in 1991 Abrantes was again replaced by a more permanent member, Henning Schmitz.[67] In 1990, after years of withdrawal from live performance, Kraftwerk began to tour Europe again regularly, including a famous appearance at the 1997 dance festival Tribal Gathering held in England.[68] During the 1998 tour Kraftwerk appeared in the United States and Japan.[69]

In July 1999 the single "Tour de France" was reissued in Europe by EMI after it had been out of print for several years.[70] It was released for the first time on CD in addition to a repressing of the twelve inch vinyl single. Both versions feature slightly altered artwork that removed the faces of Flür and Bartos from the four man cycling paceline depicted on the original cover.[71]

The single "Expo 2000" was released in December 1999.[72]

The track was remixed and re-released as "Expo Remix" in November 2000.[73]

In 1999 ex-member Flür published his autobiography in Germany, Ich war ein Roboter.[74] Later English-language editions of the book were titled Kraftwerk: I Was a Robot.[75]

In August 2003 the band released Tour de France Soundtracks, its first album of new material since 1986's Electric Café.[76]

In 2004 a box set titled 12345678, subtitled The Catalogue, was planned for a full release. It was to feature remastered editions of the group's albums from Autobahn to Tour de France Soundtracks. The item was put on hold for a release schedule.[77] The item now only exists as a promotional copy.[78][79]. Ralf Hütter, however, said in an interview to the Brazilian television that Kraftwerk will resume their work on the box set once they finish their current 2008/2009 tour.[80]

In June 2005 the band's first-ever official live album, Minimum-Maximum, which was compiled from the shows during the band's tour of spring 2004, received extremely positive reviews.[81] The album contained reworked tracks from existing studio albums. There was also a new track titled Planet Of Visions.[82] The album was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Electronic/Dance Album.[83] In December 2005, the Minimum-Maximum two-DVD set was released to accompany the album, featuring live footage of the band performing the Minimum-Maximum tracks in various venues all over the world.[84]

April 2008 saw the band back on tour in the United States leading up to its previously announced show at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival.[85]

On 22 November Kraftwerk were scheduled to headline the Global Gathering Festival in Melbourne Australia but had to cancel at the last minute due to a heart problem of Fritz Hilpert.[86]

On March 17th 2009, it was announced that Kraftwerk would play their only (indoor) United Kingdom show at the Manchester Velodrome as part of the 2009 Manchester International Festival.[87]

[edit] Band Members

[edit] Current members

- Ralf Hütter – synthesizers, organ, lead vocals; bass guitar, drums, percussion (early period)

- Fritz Hilpert – sound engineering, electronic percussion

- Henning Schmitz – sound engineering, electronic percussion, live keyboards.

- Stefan Pfaffe – video technician

[edit] Past members

- Karl Bartos – electronic percussion (1975–1991), live vibraphone (1975), keyboards on Computer World tour (1981)

- Klaus Dinger – drums (1970-1971)

- Wolfgang Flür – electronic percussion (1973–1987)

- Andreas Hohmann – drums (1970)

- Klaus Röder – guitar, electro-violin (1974)

- Michael Rother – guitar (1971)

- Florian Schneider – synthesizers, background vocals, computer-generated vocals; flutes, guitar, percussion, violin (early period) (1970-2008)

Musicians who have played in live performances with the group include:

- Fernando Abrantes – electronic percussion

- Emil Schult – guitar, electro-violin (later employed as a painter/graphic designer and lyricist)

- Plato Kostic (a.k.a. Plato Riviera) – bass guitar.

- Peter Schmidt – drums

- Houschäng Néjadepour – guitar

- Charly Weiss – drums

- Thomas Lohmann - drums

- Eberhard Kranemann – bass guitar

[edit] Departure of Florian Schneider

Florian Schneider, one of the two original co-founders of the pioneering German electronic group Kraftwerk left on 21 November 2008.[citation needed]

Commenting shortly after Schneider left the band, the Independent newspaper had this to say about Schneider's departure:

"There is something brilliantly Kraftwerkian about the news that Florian Schneider, a founder member of the German electronic pioneers, is leaving the band to pursue a solo career. Many successful bands break up after just a few years. It has apparently taken Schneider and his musical partner, Ralf Hütter, four decades to discover musical differences." [88]

[edit] Music

Like many other Krautrock bands, Kraftwerk was heavily influenced by the pioneering compositions of Karlheinz Stockhausen[citation needed]; the minimalism and non-R&B rhythms of the Velvet Underground[citation needed], as well as other radicals of the time, such as Frank Zappa, Jimi Hendrix, and the hyper-adrenalized Stooges.[citation needed] Hütter has also listed The Beach Boys as a major influence,[89] which is apparent in its 1975 chart smash, Autobahn. Hütter stated that the Beach Boys made music that sounded like California, and that Kraftwerk wanted to make music that sounded like Germany.[citation needed] Their first three albums were more free-form experimental rock without the pop hooks or the more disciplined strong structure of its later work.[citation needed] Kraftwerk, released in 1970, and Kraftwerk 2, released in 1972, were mostly exploratory jam music, played on a variety of traditional instruments including guitar, bass, drums, electric organ, flute and violin.[citation needed] Post-production modifications to these recordings were then used to distort the sound of the instruments, particularly audio-tape manipulation and multiple dubbings of one instrument on the same track. Both albums are purely instrumental.

With Ralf und Florian, released in 1973, the band began to move closer to its classic sound, relying more heavily on synthesizers and drum machines.[citation needed] Although almost entirely instrumental, the album marks Kraftwerk's first use of the vocoder, which would, in time, become one of its musical signatures.

Kraftwerk's lyrics deal with post-war European urban life and technology—traveling by car on the Autobahn, traveling by train, using home computers, and the like. Usually, the lyrics are very minimal but reveal both an innocent celebration of, and a knowing caution about, the modern world, as well as playing an integral role in the rhythmic structure of the songs. Many of Kraftwerk's songs express the paradoxical nature of modern urban life—a strong sense of alienation existing side-by-side with a celebration of the joys of modern technology.[citation needed]

All of Kraftwerk's albums from Trans-Europe Express onward have been recorded in separate versions: one with German vocals for sale in Germany, Switzerland and Austria and one with English vocals for the rest of the world, with occasional variations in other languages when conceptually appropriate.

[edit] Live shows

Live performance has always played an important part in Kraftwerk's activities. Also, despite its live shows generally being based around formal songs and compositions, live improvisation often plays a noticeable role in its performances. This trait can be traced back to the group's roots in the experimental Krautrock scene of the late 1960s[citation needed], but, significantly, it has continued to be a part of its playing even as it makes ever greater use of digital and computer-controlled sequencing in its performances.[citation needed] Some of the band's familiar compositions have been observed to have developed from live improvisations at its concerts or sound-checks.[citation needed]

[edit] 1970–1974

Early in the group's career, between 1970 and 1974, the group made sporadic live appearances. These shows were mainly in its native Germany, with occasional shows in France[citation needed], featuring a variety of line-ups. A few of these performances were for television broadcasts.[citation needed] The only constant figure in these line-ups was Schneider, whose main instrument at the time was the flute; at times also playing violin and guitar, all processed through a varied array of electronic effects. Hütter, who left the band for six months in 1971 to pursue studies in architecture, played synthesizer keyboards (including Farfisa organ and electric piano). Various other musicians who appeared on stage as part of the group during these years included Klaus Dinger (acoustic drums), Andreas Hohmann (acoustic drums), Thomas Lohmann (acoustic drums), Michael Rother (electric guitar), Charly Weiss (drums), Eberhard Kranemann (bass-guitar), Plato Kostic (bass-guitar), Emil Schult (electro-violin, electric guitar) and Klaus Roeder (electric violin, electric guitar). Later performances from 1972–73 were made as a duo, using a simple beat-box-type electronic drum machine, with preset rhythms taken from an electric organ. Later in 1973, Wolfgang Flür joined the group for rehearsals, and the unit performed as a trio on the television show, Aspekte, for German television network ZDF.[citation needed]

Documentation of this period in the group's history is sparse, with Hütter and Schneider not keen to talk about it in later interviews. A few bootleg recordings are in circulation. The only officially released material is the band's 1971 performance on the German Beat Club TV show, which is available on DVD.[citation needed]

[edit] 1975–1981

The year 1975 saw a turning point in Kraftwerk's live shows. With financial support from Phonogram in the US, it was able to undertake a multi-date tour to promote the Autobahn album. This tour took them to the US, Canada and the UK for the first time. The tour also saw a new, stable, live line-up in the form of a quartet. Hütter and Schneider both mainly played keyboard parts on synthesizers such as the Minimoog and ARP Odyssey, with Schneider's use of flute diminishing. The pair also sang vocals on stage for the first time, with Schneider also using a vocoder live. Wolfgang Flür and new recruit Karl Bartos performed live electronic percussion using custom-made (and, at the time, unique) sensor pads hit with metal sticks to complete a circuit and trigger analog synthetic percussion circuits (initially cannibalized from the aforementioned organ beat box). Bartos also used a Deagan Vibraphone on stage. The Hütter-Schneider-Bartos-Flür line-up would remain in place until the late 1980s. Emil Schult generally fulfilled the role of tour manager.[citation needed]

By the late 1970s the band's live set focused increasingly on song-based material, with greater use of vocals, less acoustic instrumentation, and the use of sequencing equipment for percussion and musical lines. The approach taken by the group was to use the sequencing equipment interactively, thus allowing room for improvisation. In 1976, the group went out on tour in support of the Radio-Activity album.[citation needed]

This tour also tested out an experimental light-beam-activated drum cage allowing Flür to trigger electronic percussion through arm and hand movements. Unfortunately, the device did not work as planned, and it was quickly abandoned. Despite the new innovations in touring, the band took a break from live performances after the Radioactivity tour of 1976. The band did, however, appear on television shows to promote the albums Trans Europe Express and The Man-Machine.[citation needed]

The band returned to the live scene with the Computer World tour of 1981, where the band effectively packed up its entire Kling Klang studio and took it on the road with them. Around this time, Wolfgang Flür was heavily involved in designing customized modular housing and packaging for the group's touring equipment. The band also developed an increasing use of visual elements in the live shows during this period. This included back-projected slides and films, increasingly synchronized with the music as the technology developed, the use of hand-held miniaturized instruments during the set, and, perhaps most famously, the use of replica mannequins of themselves to perform onstage during the song "The Robots".[citation needed]

Several bootleg recordings of this period have been widely available, some even in major retail stores, particularly from the Autobahn and Computer World tours.[citation needed]

[edit] Post 1981

The completion of the Computer World tour in the winter of 1981 precipitated an almost decade-long hiatus in Kraftwerk's live activities. Wolfgang Flür left the band in 1987 and was replaced by Fritz Hilpert. The unit did not perform live again until February 1990, with a few secret shows in Italy. Karl Bartos left the band shortly afterwards. The next proper tour was in 1991, for the album The Mix. Hütter and Schneider wished to continue the synth-pop quartet style of presentation, and recruited Fernando Abrantes as a replacement for Bartos. Abrantes was dismissed shortly after. In late 1991 Henning Schmitz was brought in to finish the remainder of the tour and to complete a new version of the quartet that remained active until 2008.[citation needed]

In 1998, the group toured the US and Japan for the first time since 1981, along with shows in Brazil and Argentina. Three new songs were performed during this period, which remain unreleased. Following this trek, the group decided to take another break.[citation needed]

In 2002 the band was touring again in Europe and Japan, using four customized Sony VAIO laptop computers, effectively leaving the entire Kling Klang studio at home in Germany. The group also obtained a new set of transparent video panels to replace its four large projection screens. This greatly streamlined the running of all of the group's sequencing, sound-generating, and visual-display software. From this point, the band's equipment increasingly reduced manual playing, replacing it with interactive control of sequencing equipment. Hütter retains the most manual performance, still playing selected musical lines by hand on a controller keyboard and singing live vocals and having a repeating ostinato. Much of Schneider's live vocoding has been replaced by software-controlled speech-synthesis techniques.[citation needed]

In January and February 2003, prior to the release of the album Tour de France Soundtracks, the group performed in Australia and New Zealand at several dates on the Big Day Out festival. In November, the group made a surprising appearance at the MTV European Music Awards in Edinburgh, Scotland, featuring a visually stunning performance of Aerodynamik. In 2004 the band toured worldwide in support of Tour de France Soundtracks.[citation needed]

In 2005 the group released its first official live album, Minimum-Maximum, recorded on the aforementioned 2004 world tour. In support of this release, Kraftwerk made another quick sweep around the globe with dates in Serbia, Bulgaria, the Republic of Macedonia, Turkey, and Greece. In December, the DVD release of Minimum-Maximum was made available.[citation needed]

In 2006 a small number of festivals were played in Norway, the Czech Republic, Spain, Belgium and Germany.[citation needed]

In April 2008 the group played three shows in US cities Minneapolis, Milwaukee, and Denver, and was a co-headliner at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival. This was its second appearance at the festival since 2004.[citation needed]

The touring quartet consisted of Ralf Hütter, Henning Schmitz, Fritz Hilpert, and video technician Stefan Pfaffe. Original member Florian Schneider was absent from the lineup. Hütter stated that he was working on other projects.[90]

In Fall and Winter 2008, shows were performed in Ireland, Poland, Ukraine, Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong and Singapore.[citation needed]

Kraftwerk lost a lawsuit in Germany's high court on 20 November determining whether artists should have the right to sample other bands' music without infringing on copyright. Kraftwerk sued rap producer Moses Pelham for sampling two seconds of their 1977 song "Metal On Metal" in the track "Nur Mir" by Sabrina Setlur.[91]

Kraftwerk's headline set that was to be played at Global Gathering in Melbourne, Australia on November 22, 2008 was cancelled moments before it was scheduled to begin. There was a commotion on and around the stage at approximately 8:25. No gear was present on the stage and at the moment the show was to begin, Ralf Hütter appeared on the stage with an MC.[86] The MC explained that the band was unable to perform due to the ill health of Fritz Hilpert. Ralf then spoke to the crowd. He apologized and said the band would do all they could to try re-schedule the show(s). He also mentioned something about Fritz having a heart condition or mild heart attack but that he was ok. The MC then told the crowd that Kraftwerk's set would be replaced by the Gorillaz Sound System. On the next day, Future Entertainment released a statement[92], which says that Fritz Hilpert has been cleared to fly and Kraftwerk will not reschedule rest of Australian tour, because Fritz is now able to play.[citation needed]

They're booked to play UK festival, Bestival, in September 2009, [93] as well as playing a series of live shows with Radiohead in a series of Central/South American concerts happening in March[94]

A Romania concert was also confirmed, on 12 June 2009 in Bucharest at the Sala Palatului Hall, as well as Zagreb INmusic festival concert on 24th and 25th June 2009.

For the 2009 Manchester International Festival, the band will be performing at the Manchester Velodrome on the 2 July.

[edit] Influence on other musicians

Kraftwerk's music has directly influenced many popular artists from many diverse genres of music.[citation needed]

Kraftwerk were also a major influence on Chicago house Music.[citation needed] Keith Farley's (Farley "Jackmaster" Funk of the Hot Mix 5) recording "Funkin With the Drums Again" are influenced by Kraftwerk's "Home Computer" and "It's More Fun to Compute".[citation needed]

While touring after the release of Astronaut in 2005, Duran Duran would signify its arrival on stage by playing "The Robots".[citation needed] This track appeared on the album Nick Rhodes and John Taylor present Only after Dark (2006).[citation needed] When Duran Duran played Broadway in November 2007, and the Lyceum in London in December 2007, they performed "Showroom Dummies" as part of its electro set.[citation needed]

Kraftwerk have also influenced celtic fusion music, most notably in the use of electronic sounds to complement traditional instruments in the music of bands such as the Peatbog Faeries[citation needed]; their fourth album was called Croftwork and featured the track "Trans-Island Express".[citation needed]

[edit] Discography

- Main article: Kraftwerk discography.

[edit] Bibliography

- 1994 : "Kraftwerk: Man, Machine and Music" by Pascal Bussy

- 1998 : "Kraftwerk: From Düsseldorf to the Future" by Tim Barr

- 1999 : "Kraftwerk: I Was a Robot" by Wolfgang Flür

- 2000 : "A Short Introduction to Kraftwerk" by Vanni Neri & Giorgio Campani

- 2002 : "Kraftwerk: The Music Makers" by Albert Koch

- 2005 : "Kraftwerk Photobook" by Kraftwerk (included in the Minimum-Maximum Notebook set)

[edit] Sheet music

Printed and digital

- 1981 : "Computer World" double-page published in Electronics & Music Maker magazine, September 1981 issue

- 1983 : "Tour de France" folded sheet, sub-published by EMI Music Publishing Ltd

- 2003 : "The Model" digital download, published by Music Sales Ltd

- 2009 : "Kraftwerk Songbook", 88 page book, published by Bosworth Music GmbH

[edit] See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Category:Kraftwerk |

[edit] References

- Bussey, P (1993). Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music. SAF Publishing.

- Flür, Wolfgang (2001). I Was A Robot. Sanctuary Publishing.

[edit] Footnotes

- ^ The Guardian, Desperately Seeking Kraftwerk

- ^ NME, Kraftwerk: Minimum-Maximum Live

- ^ John McCready on Kraftwerk

- ^ Harrington, Richard (May 27, 2005). "These Days, Kraftwerk is Packing Light". Washington post. p. WE08. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/05/26/AR2005052600677.html. Retrieved on 2006-07-06.

- ^ Gill, Andy. "Kraftwerk:".

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 17

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 19

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 23

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 32

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 33

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 55

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 50

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 67

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 163

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 45

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 45

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 61

- ^ Flür, W, I Was A Robot, Sanctuary Publishing, 2001, page 48

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 67

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 67

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 68

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 69

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 74

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 76

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 78

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 79

- ^ Flür, W, I Was A Robot, Sanctuary Publishing, 2001, page 96

- ^ Flür, W, I Was A Robot, Sanctuary Publishing, 2001, page 96

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 79

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 81

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 79

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 88

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 89

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 94

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 95

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 97

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 95

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 95

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 100

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 45

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 107

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 109

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 109

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 109

- ^ http://www.datamath.org/Speech/LanguageTranslator.htm Datamath.org Retrieved on 06-02-07

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 115

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 115

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 115

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 127

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 127

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 127

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 128

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 128

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 129

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 131

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 131

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 132

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 133

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 133

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 134

- ^ Bussey, P, Kraftwerk - Man Machine & Music, SAF Publishing 1993, page 134

- ^ Flür, W, I Was A Robot, Sanctuary Publishing, 2001, page 159

- ^ Flür, W, I Was A Robot, Sanctuary Publishing, 2001, page 159

- ^ Flür, W, I Was A Robot, Sanctuary Publishing, 2001, page 159

- ^ Flür, W, I Was A Robot, Sanctuary Publishing, 2001, page 171

- ^ Discogs, Kraftwerk Technopop - "Formations" Retrieved on March 05, 2009

- ^ Discogs, Kraftwerk Technopop - "Formations" Retrieved on March 05, 2009

- ^ 2 Cents: Kraftwerk, Tribal Gathering (May 25, 1997). Retrieved on March 05, 2009

- ^ Kraftworld, Kraftwerk 1998 Tour Retrieved on March 05, 2009

- ^ Discogs, Kraftwerk - Tour de France 1999 Retrieved on March 05, 2009

- ^ Discogs, Kraftwerk - Tour de France 1999 Retrieved on March 05, 2009

- ^ Discogs, Kraftwerk - Expo 2000 Retrieved on March 05, 2009

- ^ Discogs, Kraftwerk - Expo Remix Retrieved on March 05, 2009

- ^ Yamomusic - News Retrieved on March 06, 2009

- ^ Yamomusic - News Retrieved on March 06, 2009

- ^ Discogs, Kraftwerk - Tour de France Soundtracks Retrieved on March 09, 2009

- ^ Discogs, Kraftwerk - 12345678 Retrieved on March 09, 2009

- ^ Discogs, Kraftwerk - 12345678 Retrieved on March 09, 2009

- ^ More and more remastered Kraftwerk eight-CD promo boxed sets auctioned via eBay

- ^ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JMi7WAyIIF0

- ^ Discogs, Kraftwerk - Minimum - Maximum Retrieved on March 09, 2009

- ^ Discogs, Kraftwerk - Minimum - Maximum Retrieved on March 09, 2009

- ^ Metro Weekly - Soundwaves Retrieved on March 09, 2009

- ^ Discogs, Kraftwerk - Minimum Maximum DVD Retrieved on March 09, 2009

- ^ Kraftwerk announce US tourdates

- ^ a b "Video". Youtube. 2008-11-22. http://au.youtube.com/watch?v=3hIzQU0rAXQ. Retrieved on 2008-11-22.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Editorial, "Nice werk" [sic] (2007, 7 January.) The Independent: 28.

- ^ [2] thing.de Retrieved on 10-10-07

- ^ "Interview". The New Zealand Herald. 2008-09-27. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/entertainment/news/article.cfm?c_id=1501119&objectid=10534357&pnum=0. Retrieved on 2008-09-27.

- ^ Court rules against Kraftwerk in sampling case

- ^ Illness forces Kraftwerk to miss Melbourne Global Gathering, inthemix.com.au (2008-11-23)

- ^ Kraftwerk to headline Bestival, ventnorblog.com (2009-02-26)

- ^ http:www.radiohead.com

[edit] External links

- Kraftwerk.com—The official Kraftwerk Web site.

- Technopop—Official Kraftwerk Fan Site.

- Kraftwerk FAQ.com—The Kraftwerk FAQ: Frequently asked questions and answers.

- Kraftwerk International Discography—Comprehensive list of official releases worldwide.

- BBC Radio 1 Kraftwerk documentary—2006 Kraftwerk documentary on BBC Radio 1, with Alex Kapranos

- - Kraftwerk Vinyl Site for Collectors

|

||||||||||||||||||||