Ant colony optimization

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The ant colony optimization algorithm (ACO), is a probabilistic technique for solving computational problems which can be reduced to finding good paths through graphs.

This algorithm is a member of ant colony algorithms family, in swarm intelligence methods, and it constitutes some metaheuristic optimizations. Initially proposed by Marco Dorigo in 1992 in his PhD thesis [1] [2] , the first algorithm was aiming to search for an optimal path in a graph; based on the behavior of ants seeking a path between their colony and a source of food. The original idea has since diversified to solve a wider class of Numerical problems, and as a result, several problems have emerged, drawing on various aspects of the behavior of ants.

Contents |

[edit] Overview

[edit] Summary

In the real world, ants (initially) wander randomly, and upon finding food return to their colony while laying down pheromone trails. If other ants find such a path, they are likely not to keep travelling at random, but to instead follow the trail, returning and reinforcing it if they eventually find food (see Ant communication).

Over time, however, the pheromone trail starts to evaporate, thus reducing its attractive strength. The more time it takes for an ant to travel down the path and back again, the more time the pheromones have to evaporate. A short path, by comparison, gets marched over faster, and thus the pheromone density remains high as it is laid on the path as fast as it can evaporate. Pheromone evaporation has also the advantage of avoiding the convergence to a locally optimal solution. If there were no evaporation at all, the paths chosen by the first ants would tend to be excessively attractive to the following ones. In that case, the exploration of the solution space would be constrained.

Thus, when one ant finds a good (i.e., short) path from the colony to a food source, other ants are more likely to follow that path, and positive feedback eventually leads all the ants following a single path. The idea of the ant colony algorithm is to mimic this behavior with "simulated ants" walking around the graph representing the problem to solve.

[edit] Detailed

The original idea comes from observing the exploitation of food resources among ants, in which ants’ individually limited cognitive abilities have collectively been able to find the shortest path between a food source and the nest.

- The first ant finds the food source (F), via any way (a), then returns to the nest (N), leaving behind a trail pheromone (b)

- Ants indiscriminately follow four possible ways, but the strengthening of the runway makes it more attractive as the shortest route.

- Ants take the shortest route, long portions of other ways lose their trail pheromones.

In a series of experiments on a colony of ants with a choice between two unequal length paths leading to a source of food, biologists have observed that ants tended to use the shortest route. [3] [4] A model explaining this behaviour is as follows:

- An ant (called "blitz") runs more or less at random around the colony;

- If it discovers a food source, it returns more or less directly to the nest, leaving in its path a trail of pheromone;

- These pheromones are attractive, nearby ants will be inclined to follow, more or less directly, the track;

- Returning to the colony, these ants will strengthen the route;

- If two routes are possible to reach the same food source, the shorter one will be, in the same time, traveled by more ants than the long route will

- The short route will be increasingly enhanced, and therefore become more attractive;

- The long route will eventually disappear, pheromones are volatile;

- Eventually, all the ants have determined and therefore "chosen" the shortest route.

Ants use the environment as a medium of communication. They exchange information indirectly by depositing pheromones, all detailing the status of their "work". The information exchanged has a local scope, only an ant located where the pheromones were left has a notion of them. This system is called "Stigmergy" and occurs in many social animal societies (it has been studied in the case of the construction of pillars in the nests of termites). The mechanism to solve a problem too complex to be addressed by single ants is a good example of a self-organized system. This system is based on positive feedback (the deposit of pheromone attracts other ants that will strengthen it themselves) and negative (dissipation of the route by evaporation prevents the system from thrashing). Theoretically, if the quantity of pheromone remained the same over time on all edges, no route would be chosen. However, because of feedback, a slight variation on an edge will be amplified and thus allow the choice of an edge. The algorithm will move from an unstable state in which no edge is stronger than another, to a stable state where the route is composed of the strongest edges.

[edit] Application

Ant colony optimization algorithms have been applied to many combinatorial optimization problems, ranging from quadratic assignment to fold protein or routing vehicles and a lot of derived methods have been adapted to dynamic problems in real variables, stochastic problems, multi-targets and parallel implementations. It has also been used to produce near-optimal solutions to the travelling salesman problem. They have an advantage over simulated annealing and genetic algorithm approaches of similar problems when the graph may change dynamically; the ant colony algorithm can be run continuously and adapt to changes in real time. This is of interest in network routing and urban transportation systems.

As a very good example, ant colony optimization algorithms have been used to produce near-optimal solutions to the travelling salesman problem. The first ACO algorithm was called the Ant system [5] and it was aimed to solve the travelling salesman problem, in which the goal is to find the shortest round-trip to link a series of cities. The general algorithm is relatively simple and based on a set of ants, each making one of the possible round-trips along the cities. At each stage, the ant chooses to move from one city to another according to some rules:

- It must visit each city exactly once;

- A distant city has less chance of being chosen (the visibility);

- The more intense the pheromone trail laid out on an edge between two cities, the greater the probability that that edge will be chosen;

- Having completed its journey, the ant deposits more pheromones on all edges it traversed, if the journey is short;

- After each iteration, trails of pheromones evaporate.

[edit] "An example's Pseudo-code and formulas"

procedure ACO_MetaHeuristic

while(not_termination)

generateSolutions()

pheromoneUpdate()

daemonActions()

end while

end procedure

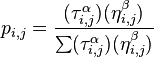

Edge Selection:

An ant will move from node i to node j with probability

where

τi,j is the amount of pheromone on edge i,j

α is a parameter to control the influence of τi,j

ηi,j is the desirability of edge i,j (a priori knowledge, typically 1 / di,j)

β is a parameter to control the influence of ηi,j

Pheromone Update

τi,j = (1 − ρ)τi,j + Δτi,j

where

τi,j is the amount of pheromone on a given edge i,j

ρ is the rate of pheromone evaporation

and Δτi,j is the amount of pheromone deposited, typically given by

where Lk is the cost of the kth ant's tour (typically length).

[edit] Common extensions

Here is some of most popular variations of ACO Algorithms

- Elitist Ant System

- The global best solution deposits pheromone on every iteration along with all the other ants

- Max-Min Ant System (MMAS)[6]

- Added Maximum and Minimum pheromone amounts [τmax,τmin]

- Only global best or iteration best tour deposited pheromone

- All edges are initialized to τmax and reinitialized to τmax when nearing stagnation.

- proportional pseudo-random rule. it has presented above [7]

- Rank-Based Ant System (ASrank)

- All solutions are ranked according to their fitness. The amount of pheromone deposited is then weighted for each solution, such that the more optimal solutions deposit more pheromone than the less optimal solutions

For some versions of the algorithm, it is possible to prove that it is convergent (ie. it is able to find the global optimum in a finite time). The first evidence of a convergence ant colony algorithm was made in 2000, the graph-based ant system algorithm, and then algorithms for ACS and MMAS. Like most metaheuristics, it is very difficult to estimate the theoretical speed of convergence. In 2004, Zlochin and his colleagues[8] have shown COA type algorithms could be assimilated methods of stochastic gradient descent, on the cross-entropy and Estimation of distribution algorithm. They proposed that these metaheuristics as a "research-based model".

[edit] other examples

The ant colony algorithm was originally used mainly to produce near-optimal solutions to the travelling salesman problem and, more generally, the problems of combinatorial optimization. It is observed that since it began its use has spread to the areas of classification and image processing.

[edit] A difficulty in definition

With an ACO algorithm, the shortest path in a graph, between two points A and B, is built from a combination of several paths. It is not easy to give a precise definition of what algorithm is or is not an ant colony, because the definition may vary according to the authors and uses. Broadly speaking, ant colony algorithms are regarded as populated metaheuristics with each solution represented by an ant moving in the search space. Ants mark the best solutions and take account of previous markings to optimize their search. They can be seen as probabilistic multi-agent algorithms using a probability distribution to make the transition between each iteration. In their versions for combinatorial problems, they use an iterative construction of solutions. According to some authors, the thing which distinguishes ACO algorithms from other relatives (such as algorithms to estimate the distribution or particle swarm optimization) is precisely their constructive aspect. In combinatorial problems, it is possible that the best solution eventually be found, even though no ant would prove effective. Thus, in the example of the Travelling salesman problem, it is not necessary that an ant actually travels the shortest route: the shortest route can be built from the strongest segments of the best solutions. However, this definition can be problematic in the case of problems in real variables, where no structure of 'neigbours' exists. The collective behaviour of social insects remains a source of inspiration for researchers. The wide variety of algorithms (for optimization or not) seeking self-organization in biological systems has led to the concept of "swarm intelligence", which is a very general framework in which ant colony algorithms fit.

[edit] Stigmergy algorithms

There is in practice a large number of algorithms claiming to be "ant colonies", without always sharing the general framework of optimization by canonical ant colonies (COA). In practice, the use of an exchange of information between ants via the environment (a principle called "Stigmergy") is deemed enough for an algorithm to belong to the class of ant colony algorithms. This principle has led some authors to create the term "value" to organize methods and behavior based on search of food, sorting larvae, division of labour and cooperative transportation. [9].

[edit] Related methods

- Genetic algorithms (GA) maintain a pool of solutions rather than just one. The process of finding superior solutions mimics that of evolution, with solutions being combined or mutated to alter the pool of solutions, with solutions of inferior quality being discarded.

- Simulated annealing (SA) is a related global optimization technique which traverses the search space by generating neighboring solutions of the current solution. A superior neighbor is always accepted. An inferior neighbor is accepted probabilistically based on the difference in quality and a temperature parameter. The temperature parameter is modified as the algorithm progresses to alter the nature of the search.

- Tabu search (TS) is similar to simulated annealing in that both traverse the solution space by testing mutations of an individual solution. While simulated annealing generates only one mutated solution, tabu search generates many mutated solutions and moves to the solution with the lowest fitness of those generated. To prevent cycling and encourage greater movement through the solution space, a tabu list is maintained of partial or complete solutions. It is forbidden to move to a solution that contains elements of the tabu list, which is updated as the solution traverses the solution space.

- Artificial immune system (AIS) algorithms are modeled on vertebrate immune systems.

- Particle swarm optimization (PSO) another very successful Swarm intelligence method

[edit] History

Chronology of COA Algorithms.

Chronology of Ant colony optimization algorithms.

- 1959, Pierre-Paul Grass invented the theory of Stigmergy to explain the behavior of nest building in termites[10];

- 1983, Deneubourg and his colleagues studied the collective behavior of ants[11];

- 1988, and Moyson Manderick have an article on self-organization among ants[12];

- 1989, the work of Goss, Aron, Deneubourg and Pasteels on the collective behavior of Argentine ants, which will give the idea of Ant colony optimization algorithms[3];

- 1989, implementation of a model of behavior for food by Ebling and his colleagues [13];

- 1991, M. Dorigo proposed the Ant System in his doctoral thesis (which was published in 1992[2] with V. Maniezzo and A. Colorni). a technical report[14] was published five years later[5];

- 1995, Bilchev and Parmee publish the first attempt to adapt ongoing problems [15];

- 1996, publication of the article on the Ant[5];

- 1996, Hoos and Stützle invent the MAX-MIN Ant Sytem [6];

- 1997, Gambardella Dorigo and publish the Ant Colony [7];

- 1997, Schoonderwoerd and his colleagues developed the first application to telecommunication networks [16];

- 1997, Martinoli and his colleagues used ACO Algorithms to control robots [17]

- 1998, Dorigo launches first conference dedicated to the ACO algorithms[18];

- 1998, Stützle proposes initial parallel implementations [19];

- 1999, Bonabeau and his colleagues have published a book dealing mainly artificial ants [20]

- 1999, first applications for vehicle routing, the quadratic assignment, the multi-dimensional Knapsack problem;

- 2000, special issue of a journal on the ACO algorithms[21]

- 2000, first applications to the scheduling, scheduling sequence and the satisfaction of constraints;

- 2000, Gutjahr provides the first evidence of convergence for an algorithm of ant colonies[22]

- 2001, the first use of COA Algorithms by companies (Eurobios and AntOptima);

- 2001, IREDA and his colleagues published the first multi-objective algorithm [23]

- 2002, first applications in the design of schedule, Bayesian networks;

- 2002, Bianchi and her colleagues suggested the first algorithm for stochastic problem[24];

- 2004, Zlochin and Dorigo show that some algorithms are equivalent to the stochastic gradient descent, the cross-entropy and algorithms to estimate distribution [8]

- 2005, first applications to folding proteins.

[edit] References

- ^ A. Colorni, M. Dorigo et V. Maniezzo, Distributed Optimization by Ant Colonies, actes de la première conférence européenne sur la vie artificielle, Paris, France, Elsevier Publishing, 134-142, 1991.

- ^ a b M. Dorigo, Optimization, Learning and Natural Algorithms, PhD thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Italie, 1992.

- ^ a b S. Goss, S. Aron, J.-L. Deneubourg et J.-M. Pasteels, The self-organized exploratory pattern of the Argentine ant, Naturwissenschaften, volume 76, pages 579-581, 1989

- ^ J.-L. Deneubourg, S. Aron, S. Goss et J.-M. Pasteels, The self-organizing exploratory pattern of the Argentine ant, Journal of Insect Behavior, volume 3, page 159, 1990

- ^ a b c M. Dorigo, V. Maniezzo, et A. Colorni, Ant system: optimization by a colony of cooperating agents, IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics--Part B , volume 26, numéro 1, pages 29-41, 1996.

- ^ a b T. Stützle et H.H. Hoos, MAX MIN Ant System, Future Generation Computer Systems, volume 16, pages 889-914, 2000

- ^ a b M. Dorigo et L.M. Gambardella, Ant Colony System : A Cooperative Learning Approach to the Traveling Salesman Problem, IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation, volume 1, numéro 1, pages 53-66, 1997.

- ^ a b M. Zlochin, M. Birattari, N. Meuleau, et M. Dorigo, Model-based search for combinatorial optimization: A critical survey, Annals of Operations Research, vol. 131, pp. 373-395, 2004.

- ^ A. Ajith; G. Crina; R. Vitorino (éditeurs), Stigmergic Optimization, Studies in Computational Intelligence , volume 31, 299 pages, 2006. ISBN 978-3-540-34689-0

- ^ P.-P. Grassé, La reconstruction du nid et les coordinations inter-individuelles chez Belicositermes natalensis et Cubitermes sp. La théorie de la Stigmergie : Essai d’interprétation du comportement des termites constructeurs, Insectes Sociaux, numéro 6, p. 41-80, 1959.

- ^ J.L. Denebourg, J.M. Pasteels et J.C. Verhaeghe, Probabilistic Behaviour in Ants : a Strategy of Errors?, Journal of Theoretical Biology, numéro 105, 1983.

- ^ F. Moyson, B. Manderick, The collective behaviour of Ants : an Example of Self-Organization in Massive Parallelism, Actes de AAAI Spring Symposium on Parallel Models of Intelligence, Stanford, Californie, 1988.

- ^ M. Ebling, M. Di Loreto, M. Presley, F. Wieland, et D. Jefferson,An Ant Foraging Model Implemented on the Time Warp Operating System, Proceedings of the SCS Multiconference on Distributed Simulation, 1989

- ^ Dorigo M., V. Maniezzo et A. Colorni, Positive feedback as a search strategy, rapport technique numéro 91-016, Dip. Elettronica, Politecnico di Milano, Italy, 1991

- ^ G. Bilchev et I. C. Parmee, The Ant Colony Metaphor for Searching Continuous Design Spaces, Proceedings of the AISB Workshop on Evolutionary Computation. Terence C. Fogarty (éditeurs), Evolutionary Computing Springer-Verlag, pages 25-39, avril 1995.

- ^ R. Schoonderwoerd, O. Holland, J. Bruten et L. Rothkrantz, Ant-based load balancing in telecommunication networks, Adaptive Behaviour, volume 5, numéro 2, pages 169-207, 1997

- ^ A. Martinoli, M. Yamamoto, et F. Mondada, On the modelling of bioinspired collective experiments with real robots, Fourth European Conference on Artificial Life ECAL-97, Brighton, UK, juillet 1997.

- ^ M. Dorigo, ANTS’ 98, From Ant Colonies to Artificial Ants : First International Workshop on Ant Colony Optimization, ANTS 98, Bruxelles, Belgique, octobre 1998.

- ^ T. Stützle, Parallelization Strategies for Ant Colony Optimization, Proceedings of PPSN-V, Fifth International Conference on Parallel Problem Solving from Nature, Springer-Verlag, volume 1498, pages 722-731, 1998.

- ^ É. Bonabeau, M. Dorigo et G. Theraulaz, Swarm intelligence, Oxford University Press, 1999.

- ^ M. Dorigo , G. Di Caro et T. Stützle, special issue on "Ant Algorithms", Future Generation Computer Systems, volume 16, numéro 8, 2000

- ^ W.J. Gutjahr, A graph-based Ant System and its convergence, Future Generation Computer Systems, volume 16, pages 873-888, 2000.

- ^ S. Iredi, D. Merkle et M. Middendorf, Bi-Criterion Optimization with Multi Colony Ant Algorithms, Evolutionary Multi-Criterion Optimization, First International Conference (EMO’01), Zurich, Springer Verlag, pages 359-372, 2001.

- ^ L. Bianchi, L.M. Gambardella et M.Dorigo, An ant colony optimization approach to the probabilistic traveling salesman problem, PPSN-VII, Seventh International Conference on Parallel Problem Solving from Nature, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Springer Verlag, Berlin, Allemagne, 2002.

Sunil

[edit] Publications (selected)

- M. Dorigo, 1992. Optimization, Learning and Natural Algorithms, PhD thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Italy.

- M. Dorigo, V. Maniezzo & A. Colorni, 1996. "Ant System: Optimization by a Colony of Cooperating Agents", IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics–Part B, 26 (1): 29–41.

- M. Dorigo & L. M. Gambardella, 1997. "Ant Colony System: A Cooperative Learning Approach to the Traveling Salesman Problem". IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation, 1 (1): 53–66.

- M. Dorigo, G. Di Caro & L. M. Gambardella, 1999. "Ant Algorithms for Discrete Optimization". Artificial Life, 5 (2): 137–172.

- E. Bonabeau, M. Dorigo et G. Theraulaz, 1999. Swarm Intelligence: From Natural to Artificial Systems, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513159-2

- M. Dorigo & T. Stützle, 2004. Ant Colony Optimization, MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-04219-3

- M. Dorigo, 2007. "Ant Colony Optimization". Scholarpedia.

- C. Blum, 2005 "ant colony optimization:introduction and recent trends" physics of life review(2) 353-373

[edit] External links

- Ant Colony Optimization Home Page

- VisualBots - Freeware multi-agent simulator in Microsoft Excel. Sample programs include genetic algorithm, ACO, and simulated annealing solutions to TSP.

- AntSim v1.0 A visual simulation of Ant Colony Optimization with artificial ants. (Windows Application)

- Myrmedrome A visual simulation of Ant Colony Optimization with artificial ants. (Windows and Linux Application)

- Ant Farm Simulator A simulation of ants food-gathering behaviour (Windows Application and source code available)

- ANT Colony Algorithm A Java Simulation of the Path Optimisation, on a changing ground. Presentation and source code available.

- Ant Colony Optimization A Java Applet demonstrating Ant Colony Optimization for the Traveling Salesman Problem.

- Antnet - Ant algorithm in C++ for Ns-2.33 A Ant algorithm in C++ for Ns-2.33 demonstrating Ant Colony Optimization .