Long s

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

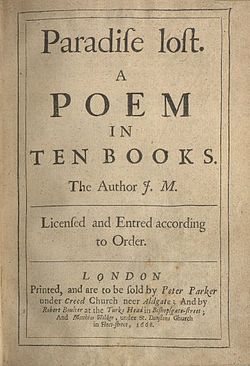

The long, medial or descending s (ſ) is a form of the minuscule letter 's' formerly used where 's' occurred in the middle or at the beginning of a word, for example ſinfulneſs ("sinfulness"). The modern letterform was called the terminal or short s.

Contents |

[edit] History

The long 's' is derived from the old Roman cursive medial s, which was very similar to an elongated check mark. When the distinction between upper case (capital) and lower case (small) letter-forms became established, towards the end of the eighth century, it developed a more vertical form.[1] At this period it was occasionally used at the end of a word, a practice which quickly died out but was occasionally revived in Italian printing between about 1465 and 1480. The short 's' was also normally used in the combination 'sf', for example in 'ſatisfaction'. In German written in fraktur, the rules are more complicated: short 's' also appears at the end of distinct elements within a word.

The long 's' is subject to confusion with the lower case or minuscule 'f', sometimes even having an 'f'-like nub at its middle, but on the left side only, in various kinds of Roman typeface and in blackletter. There was no nub in its italic typeform, which gave the stroke a descender curling to the left—not possible with the other typeforms mentioned without kerning.

The nub acquired its form in the blackletter style of writing. What looks like one stroke was actually a wedge pointing downward, whose widest part was at that height (x-height), and capped by a second stroke forming an ascender curling to the right. Those styles of writing and their derivatives in type design had a cross-bar at height of the nub for letters 'f' and 't', as well as 'k'. In Roman type, these disappeared except for the one on the medial 's'.

The long 's' was used in ligatures in various languages. Three examples were for 'si', 'ss', and 'st', besides the German 'double s' 'ß'.

Long 's' fell out of use in Roman and italic typography well before the middle of the 19th century; in French the change occurred from about 1780 onwards, in English in the decades before and after 1800, and in the United States around 1820. This may have been spurred by the fact that long 's' looks somewhat like 'f' (in both its Roman and italic forms), whereas short 's' did not have the disadvantage of looking like another letter, making it easier to read correctly, especially for people with vision problems.

Long 's' survives in German blackletter typefaces. The present-day German 'double s' 'ß' (das Eszett "the ess-zed" or scharfes-ess, the sharp S) is an atrophied ligature form representing either 'ſz' or 'ſs' (see ß for more). Greek also features a normal sigma 'σ' and a special terminal form 'ς', which may have supported the idea of specialized 's' forms. In Renaissance Europe a significant fraction of the literate class was familiar with Greek.

[edit] Modern usage

The long 's' is represented in Unicode by the sign U+017F in the Latin Extended-A range, and may be represented in HTML as ſ or ſ.

the integral of f |

The long 's' survives in elongated form, and with an italic-style curled descender, as the integral symbol ∫ used in calculus; Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz based the character on the Latin word summa (sum), which he wrote ſumma. This use first appeared publicly in his paper De Geometria, published in Acta Eruditorum of June, 1686,[2] but he had been using it in private manuscripts since at least 1675.[3]

In linguistics a similar glyph (ʃ) (called "esh") is used in the International Phonetic Alphabet, in which it represents the voiceless postalveolar fricative, the first sound in the English word shun.

In Scandinavian and German-speaking countries, relics of the long ſ continue to be seen in signs and logos that use various forms of fraktur typefaces. Examples include the logos of the Norwegian newspapers Aftenpoſten and Adresſeaviſen; the packaging logo for Finnish 'Siſu' pastilles; and the Jägermeiſter logo.

The similarity between the printed long 'ſ' and 'f', and modern-day unfamiliarity with the former letter has been the subject of much humour based on the intentional misreading of s as f, e.g. pronouncing Greensleeves as Greenfleeves and song as fong in a Flanders and Swann monologue[4].

Another survival of the long s was the abbreviation used in British English for shilling, as in 5/-, where the forward slash stood in for the long s which had been long forgotten by all but antiquarians.

[edit] See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Langes s |

- ß (Eszett)

- Esh (letter)

- Integral sign

- R rotunda

[edit] Notes

- ^ Lyn Davies. A Is for Ox, London: 2006. Folio Society.

- ^ Mathematics and its History, John Stillwell, Springer 1989, p. 110

- ^ Early Mathematical Manuscripts of Leibniz, J. M. Child, Open Court Publishing Co., 1920, pp. 73–74, 80.

- ^ "The Greensleeves Monologue Annotated". http://www.beachmedia.com/gorbuduc.html.

[edit] External links

- James Mosley on long s

- The Straight Dope on long s

- The Rules for Long S

- The Long and the Short of the Letter S

| The Basic modern Latin alphabet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aa | Bb | Cc | Dd | Ee | Ff | Gg | Hh | Ii | Jj | Kk | Ll | Mm | Nn | Oo | Pp | Rr | Ss | Tt | Uu | Vv | Ww | Xx | Yy | Zz | |

|

history • palaeography • derivations • diacritics • punctuation • numerals • Unicode • list of letters • ISO/IEC 646 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||