Calligraphy

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Calligraphy (from Greek κάλλος kallos "beauty" + γραφή graphẽ "writing") is the art of writing (Mediavilla 1996: 17). A contemporary definition of calligraphic practice is "the art of giving form to signs in an expressive, harmonious and skillful manner" (Mediavilla 1996: 18). The story of writing is one of aesthetic evolution framed within the technical skills, transmission speed(s) and materials limitations of a person, time and place (Diringer 1968: 441). A style of writing is described as a script, hand or alphabet (Fraser & Kwiatkowski 2006; Johnston 1909: Plate 6).

Modern calligraphy ranges from functional hand lettered inscriptions and designs to fine art pieces where the abstract expression of the handwritten mark may or may not supersede the legibility of the letters (Mediavilla 1996). Classical calligraphy differs from typography and non-classical hand-lettering, though a calligrapher may create all of these; characters are historically disciplined yet fluid and spontaneous, improvised at the moment of writing (Pott 2006 & 2005; Zapf 2007 & 2006). Calligraphy continues to flourish in the forms of wedding and event invitations, font design/ typography, original hand-lettered logo design, religious art, various announcements/ graphic design/ commissioned calligraphic art, cut stone inscriptions and memorial documents. Also props and moving images for film and television, testimonials, birth and death certificates/maps, and other works involving writing (see for example Letter Arts Review; Propfe 2005; Geddes & Dion 2004).

Contents |

[edit] Western calligraphy

[edit] Historical evolution

Western calligraphy is recognizable by the use of the Roman alphabet, which evolved from the Phoenician, Greek, and Etruscan alphabets. The first Roman alphabet appeared about 600 BC, in Rome, and by the first century developed into Roman imperial capitals carved on stones, Rustic capitals painted on walls, and Roman cursive for daily use. In the second and third centuries the Uncial lettering style developed. It was the monasteries which preserved the calligraphy traditions during the fourth and fifth centuries, when the Roman Empire fell and Europe entered the Dark Ages.[1]

At the height of the Roman Empire its power reached as far as Great Britain; when the empire fell, its literary influence remained. The Semi-uncial generated the Irish Semi-uncial, the small Anglo-Saxon. Each region seemed to have develop its own standards following the main monastery of the region (i.e. Merovingian script, Laon script, Luxeuil script, Visigothic script, Beneventan script) which are mostly cursive and hardly readable.

Raising of the Carolingian Empire encouraged to set a new standardized script, developed by several famous monasteries (including Corbie Abbey and Beauvais) around the eighth century. Finally the script from Saint Martin de Tours was set as the Imperial standard, named the Carolingian script (or "the Caroline"). From the powerful Carolingian Empire, this standard also became used in neighbouring kingdoms.

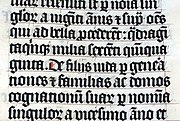

In the eleventh century, the Caroline evolved into the Gothic script, which was more compact and making it possible to fit more text on a page[2]. The Gothic calligraphy styles became dominant in northern Europe; and in 1454 AD, when Johannes Gutenberg developed the first printing press, in Mainz, Germany, he adopted the Gothic style, making it the first typeface[3].

In the sixteenth century, the rediscovery of old Carolingian texts encouraged the creation of the Antiqua script (about 1470). The seventeenth century saw the Batarde script from France, and the eighteenth century saw the English script spread across Europe and world by their books.

The contemporary typefaces found on every computer, whether in simple word processing programs like Microsoft Word or Apple Pages, through to a professional designer's software package like Adobe InDesign, owe a considerable debt to the past and to a small number of professional typeface designers today (Zapf 2007; Mediavilla 2006; Henning 2002).

[edit] Features of Western calligraphy

Sacred Western calligraphy has some special features, such as the illumination of the first letter of each book or chapter in medieval times. A decorative "carpet page" may precede, filled with geometrical, bestial and colourful depictions. The Lindisfarne Gospels (715-720 AD) is an early example (Brown 2004).

As for Chinese or Arabian calligraphies, Western calligraphic script had strict rules and shapes. Quality writing had a rhythm and regularity to the letters, with a "geometrical" good order of the lines on the pages. Each character had, and often still has, a precise stroke order.

Unlike a typeface, irregularity in the characters' size, style and colors adds meaning to the Greek translation "beautiful letters". The content may be completely illegible, but no less meaningful to a viewer with some empathy for the work on view. Many of the themes and variations of today's contemporary Western calligraphy are found in the pages of the Saint John's Bible.

[edit] Eastern Asian calligraphy

|

|

[edit] Names and features

Asian calligraphy typically uses ink brushes to write Chinese characters (called Hanzi in Chinese, Hanja in Korean, Kanji in Japanese, and Hán Tự in Vietnamese). Calligraphy (in Chinese, Shufa 書法, in Korean, Seoye 書藝, in Japanese Shodō 書道, all meaning "the way of writing") is considered an important art in East Asia and the most refined form of East Asian painting.

Calligraphy has also influenced ink and wash painting, which is accomplished using similar tools and techniques. Calligraphy has influenced most major art styles in East Asia, including sumi-e, a style of Chinese, Korean, and Japanese painting based entirely on calligraphy.

[edit] Historical evolution of Eastern calligraphy

- Ancient China

In ancient China, the oldest Chinese characters existing are Jiǎgǔwén characters carved on ox scapula and tortoise plastrons, because brush-written ones have decayed over time. During the divination ceremony, after the cracks were made, the characters were written with a brush on the shell or bone to be later carved.(Keightley, 1978).

With the development of Jīnwén (Bronzeware script) and Dàzhuàn (Large Seal Script) "cursive" signs continued. Moreover, each archaic kingdom of current China had its own set of characters.

- Imperial China

In Imperial China, the graphs on old steles — some dating from 200 BC, and in Xiaozhuan style — are still accessible.

About 220 BC, the emperor Qin Shi Huang, the first to conquer the entire Chinese basin, imposed several reforms, among them Li Si's character uniformisation, which created a set of 3300 standardized Xiǎozhuàn characters[4]. Despite the fact that the main writing implement of the time was already the brush, few papers survive from this period, and the main examples of this style are on steles.

The Lìshū style (clerical script) which is more regularized, and in some ways similar to modern text, was then developed.

Kǎishū style (traditional regular script) — still in use today — is even more regularized. The Kaishu shape of characters 1000 years ago was mostly similar to that at the end of Imperial China. But small changes have be made, for example in the shape of 广 which is not absolutely the same in the Kangxi dictionary of 1716 as in modern books. The Kangxi and current shapes have tiny differences, while stroke order is still the same, according to old style[5].

Kǎishū simplified Chinese script is in fact a selection of long-time pre-existing easiest variants, which were unconventional or localy used for centuries, and understood but always rejected in official texts. By selecting this easiest variants, the Chinese government created in 1956 a new set of official variants to use, simpler, to ease learning and increase literacy. It has only eight basic strokes and is used by most students and apprentinces today.

- Cursive styles and hand-written styles

Cursive styles such as Xíngshū (semi-cursive or running script) and Cǎoshū (cursive or grass script) are "high speed" calligraphic styles, where each move made by the writing tool is visible. These styles especially like to play with stroke order rules, creating new visual effects. They were invented as derivated work from Clerical script, in same time than Regular script (Han dynasty), but Xíngshū and Cǎoshū were use for personnal notes only, and were never use as standard. They quickly became artistical play, on the side of the official Regular style.

- Printed and computer styles

An example of the modern printed style is Songti (style of the Song Dynasty's book press), and the dozens of computer ones. These sets are other "styles", but not calligraphic ones, as they are not hand written.

[edit] Indian calligraphy

On the subject of Indian calligraphy, Anderson 2008 writes:

Aśoka's edicts (c. 265–238 BC) were committed to stone. These inscriptions are stiff and angular in form. Following the Aśoka style of Indic writing, two new calligraphic types appear: Kharoṣṭī and Brāhmī. Kharoṣṭī was used in the northwestern regions of India from the 3rd century BC to the 4th century of the Christian Era, and it was used in Central Asia until the 8th century.

Copper was a favoured material for Indic inscriptions. In the north of India, birch bark was used as a writing surface as early as the 2nd century AD. Many Indic manuscripts were written on palm leaves, even after the Indian languages were put on paper in the 13th century. Both sides of the leaves were used for writing. Long rectangular strips were gathered on top of one another, holes were drilled through all the leaves, and the book was held together by string. Books of this manufacture were common to Southeast Asia. The palm leaf was an excellent surface for penwriting, making possible the delicate lettering used in many of the scripts of southern Asia.

[edit] Nepalese calligraphy

Nepalese calligraphy has a huge impact on Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. Ranjana script is the primary form of this calligraphy. The script itself and its derivatives (like Lantsa, Phagpa, Kutila) are used in Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan, Leh, Mongolia, coastal China, Japan and Korea to write "Om mane pame om" and other sacred Buddhist texts, mainly those derived from Sanskrit and Pali.

[edit] Tibetan calligraphy

Calligraphy is central in Tibetan culture. The script is derived from Indic scripts. The nobles of Tibet, such as the High Lamas and inhabitants of the Potala Palace, were usually capable calligraphers. Tibet has been a center of Buddhism for several centuries, and that religion places a great deal of significance on written word. This does not provide for a large body of secular pieces, although they do exist (but are usually related in some way to Tibetan Buddhism). Almost all high religious writing involved calligraphy, including letters sent by the Dalai Lama and other religious and secular authority. Calligraphy is particularly evident on their prayer wheels, although this calligraphy was forged rather than scribed, much like Arab and Roman calligraphy is often found on buildings. Although originally done with a reed, Tibetan calligraphers now use chisel tipped pens and markers as well.

[edit] Iranian calligraphy

Persian calligraphy is the calligraphy of Persian writing system. The history of calligraphy in Persia dates back to the pre-Islam era. In Zoroastrianism beautiful and clear writings were always praised.

[edit] History and evolution

It is believed that ancient Persian script was invented by about 500-600 BC to provide monument inscriptions for the Achaemenid kings. These scripts consisted of horizontal, vertical, and diagonal nail-shape letters and that is the reason in Persian it is called "Script of Nails" (Khat-e-Mikhi). Centuries later, other scripts such as "Pahlavi" and "Avestaee" scripts became popular in ancient Persia. After initiation of Islam in the 7th century, Persians adapted Arabic alphabet to Persian language and developed contemporary Persian alphabet. Arabic alphabet has 28 characters and Iranians added another four letters in it to arrive at existing 32 Persian letters.

[edit] Major contemporary scripts

"Nasta'liq" is the most popular contemporary style among classical Persian calligraphy scripts and Persian calligraphers call it "Bride of the Calligraphy Scripts". This calligraphy style has been based on such a strong structure that it has changed very little since. Mir Ali Tabrizi had found the optimum composition of the letters and graphical rules so it has just been fine-tuned during the past seven centuries. It has very strict rules for graphical shape of the letters and for combination of the letters, words, and composition of the whole calligraphy piece.

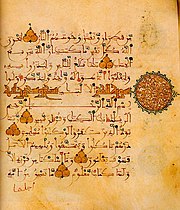

[edit] Islamic calligraphy

Islamic calligraphy (calligraphy in Arabic is Khatt ul-Yad خط اليد) is an aspect of Islamic art that has evolved alongside the religion of Islam and the Arabic language.

Arabic calligraphy is associated with geometric Islamic art (arabesque) on the walls and ceilings of mosques as well as on the page. Contemporary artists in the Islamic world draw on the heritage of calligraphy to use calligraphic inscriptions or abstractions.

Instead of recalling something related to the spoken word, calligraphy for Muslims is a visible expression of the highest art of all, the art of the spiritual world. Calligraphy has arguably become the most venerated form of Islamic art because it provides a link between the languages of the Muslims with the religion of Islam. The holy book of Islam, al-Qur'an, has played an important role in the development and evolution of the Arabic language, and by extension, calligraphy in the Arabic alphabet. Proverbs and passages from the Qur'an are still sources for Islamic calligraphy.

There was a strong parallel tradition to that of the Islamic, among Aramaic and Hebrew scholars, seen in such works as the Hebrew illuminated bibles of the 9th and 10th centuries.

[edit] Maya calligraphy

| This section requires expansion. |

Maya calligraphy was expressed as glyphs; modern Mayan calligraphy is mainly used on seals and monuments in the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. Glyphs are rarely used in government offices, however in Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo, Mayan calligraphy is written with Latin alphabet characters. Some commercial companies in Southern Mexico use glyphs as symbols of their business. Some community associations and modern Maya brotherhoods use glyphs as symbols of their groups.

Most of the archaeological sites in Mexico such as Chichen Itza, Labna, Uxmal, Edzna, Calakmul, etc. have glyphs in their structures. Stone carved monuments also known as stele are a common source of ancient Maya calligraphy.

[edit] Tools

The principal tools for a calligrapher are the pen, which may be flat- or round-nibbed, and the brush (Reaves & Schulte 2006; Child 1985; Lamb 1956). For some decorative purposes, multi-nibbed pens—steel brushes—can be used. However, works have also been made with felt-tip and ballpoint pens, although these works do not employ angled lines. Ink for writing is usually water-based and much less viscous than the oil based inks used in printing. High quality paper, which has good consistency of porosity, will enable cleaner lines,[citation needed] although parchment or vellum is often used, as a knife can be used to erase work on them and a light box is not needed to allow lines to pass through it. In addition, light boxes and templates are used to achieve straight lines without pencil markings detracting from the work. Lined paper, either for a light box or direct use, is most often lined every quarter or half inch, although inch spaces are occasionally used, such as with litterea unciales (hence the name), and college ruled paper acts as a guideline often as well.[6]

[edit] See also

- Asemic writing

- Chirography

- Typographic Emphasis

- Ink

- List of prominent calligraphers

- List of typographic features

- Paper

- Pen

- Penmanship

- Punchcutting

- Stylus

- Typography

- Typographic units

- Marc Drogin - Author of books Medieval Calligraphy: Its History and Technique, and Calligraphy of the Middle Ages and How to Do It

[edit] Notes

- ^ V. Sabard, V. Geneslay, L. Rébéna, Calligraphie latine, initiation, ed. Fleurus, Paris. 7th edition, 2004, pages 8 to 11

- ^ Patricia lovett. Calligraphy and Illumination Abrams 2000, p.72

- ^ Patricia lovett. Calligraphy and Illumination Abrams 2000, p.141

- ^ Fazzioli, Edoardo. Chinese calligraphy : from pictograph to ideogram : the history of 214 essential Chinese/Japanese characters. calligraphy by Rebecca Hon Ko. New York: Abbeville Press. pp. 13. ISBN 0896597741. "And so the first Chinese dictionary was born, the Sān Chāng, containing 3,300 characters"

- ^ 康熙字典 Kangxi Zidian, 1716. Scanned version available at www.kangxizidian.com. See by example the radicals 卩, 厂 or 广, p.41. The 2007 common shape for those characters doesn't allow guessing the stroke order, but old versions, visible on the Kangxi Zidian p.41 clearly allow the stroke order to be determined.

- ^ Calligraphy Islamic website

[edit] References

See respectives articles.

- Brown, M.P. (2004) Painted Labyrinth: The World of the Lindisfarne Gospel. Revised Ed. British Library.

- Child, H. ed. (1985) The Calligrapher's Handbook. Taplinger Publishing Co.

- Diringer, D. (1968) The Alphabet: A Key to the History of Mankind 3rd Ed. Volume 1 Hutchinson & Co. London

- Fraser, M., & Kwiatowski, W. (2006) Ink and Gold: Islamic Calligraphy. Sam Fogg Ltd. London

- Geddes, A., & Dion, C. (2004) Miracle: a celebration of new life. Photogenique Publishers Auckland.

- Henning, W.E. (2002) An elegant hand : the golden age of American penmanship and calligraphy ed. Melzer, P. Oak Knoll Press New Castle, Delaware

- Johnston, E. (1909) Manuscript & Inscription Letters: For schools and classes and for the use of craftsmen, plate 6. San Vito Press & Double Elephant Press 10th Impression

- Lamb, C.M. ed. (1956) Calligrapher's Handbook. Pentalic 1976 ed.

- Letter Arts Review

- Mediavilla, C. (2006) Histoire de la CALLIGRAPHIE Francaise. Albin Michel, France.

- Mediavilla, C. (1996) Calligraphy. Scirpus Publications

- Pott, G. (2006) Kalligrafie: Intensiv Training Verlag Hermann Schmidt Mainz

- Pott, G. (2005) Kalligrafie:Erste Hilfe und Schrift-Training mit Muster-Alphabeten Verlag Hermann Schmidt Mainz

- Propfe, J. (2005) SchreibKunstRaume: Kalligraphie im Raum Verlag George D.W. Callwey GmbH & Co.K.G. Munich

- Reaves, M., & Schulte, E. (2006) Brush Lettering: An instructional manual in Western brush calligraphy, Revised Edition, Design Books New York.

- Zapf, H. (2007) Alphabet Stories: A Chronicle of technical develoments, Cary Graphic Arts Press, Rochester, New York

- Zapf, H. (2006) The world of Alphabets: A kaleidoscope of drawings and letterforms, CD-ROM

- Anderson, D. M. (2008), Indic calligraphy, Encyclopedia Britannica 2008.

[edit] External links

| This article's external links may not follow Wikipedia's content policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive or inappropriate external links. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Calligraphy |

| Look up calligraphy in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

[edit] Chinese (brush) calligraphy

- Chinese Calligraphy at China Online Museum

- Famous Calligraphers and their Galleries in Chinese history

- Brush Calligraphy Gallery Art of Chinese Calligraphy

[edit] Western Calligraphy

- Contemporary Museum of Calligraphy Contemporary Museum of Calligraphy

- Letter Exchange An organization promoting lettering in all media

- Cynscribe World Wide Web Calligraphy Directory

- Society of Scribes, New York City, NY, US

- Society of Scribes and Illuminators, London, England

- International Association of Master Penmen, Engrossers and Teachers of Handwriting, Webster, NY, US

- Kaligrafos - The Dallas Calligraphy Society Promoting the calligraphic arts

- New Zealand Calligraphers A national network of affiliated calligraphy guilds

- The Edward Johnston Foundation - Research centre for calligraphy

- Alcuino - Association for the Recovery of Ancient Calligraphy Association ALCUINO, España

[edit] Islamic calligraphy

- Calligraphy Islamic - Islamic Calligraphy

- Gallery of Arabic calligraphy - National Institute for Technology and Liberal Education

- Samples of Islamic calligraphy

- Islamic Calligraphy in the Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

[edit] Calligraphy of other scripts

- Mongolian: Inkway Calligraphy

- Nepali: Nepali Calligraphy - Calligraphy

- Tibetan: History and reproductions of Tibetan Calligraphy

- Tibetan: Tibetan Calligraphy - How to write the script.

- Punjabi: [1]

[edit] Japanese calligraphy

[edit] Calligraphy museums

- Museum of calligraphy and miniature graphics in Pettenbach (Austria)

- Manuscript museum at the Library of Alexandria

- Naritasan Calligraphy museum

- The Modern Calligraphy Collection of the National Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum

- Ditchling Museum

- Klingspor Museum

- Sakip Sabanci Museum

[edit] International Competitions

- C.A.U.S. – Alphabets and Calligraphy [2]

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||