Alcubierre drive

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Alcubierre metric, also known as the Alcubierre drive or Warp Drive, is a speculative mathematical model of a spacetime exhibiting features reminiscent of the fictional "warp drive" from Star Trek, which can travel "Faster-than-light" (although not in a local sense - see below).

In 1994, the Mexican physicist Miguel Alcubierre proposed a method of stretching space in a wave which would in theory cause the fabric of space ahead of a spacecraft to contract and the space behind it to expand.[1] The ship would ride this wave inside a region known as a warp bubble of flat space. Since the ship is not moving within this bubble, but carried along as the region itself moves, conventional relativistic effects such as time dilation do not apply in the way they would in the case of a ship moving at high velocity through flat spacetime. Also, this method of travel does not actually involve moving faster than light in a local sense, since a light beam within the bubble would still always move faster than the ship; it is only "faster than light" in the sense that, thanks to the contraction of the space in front of it, the ship could reach its destination faster than a light beam restricted to travelling outside the warp bubble. Thus, the Alcubierre drive does not contradict the conventional claim that relativity forbids a slower-than-light object to accelerate to faster-than-light speeds. However, there are no known methods to create such a warp bubble in a region that does not already contain one, or to leave the bubble once inside it, so the Alcubierre drive remains a theoretical concept at this time.

Contents |

[edit] Alcubierre Metric

The Alcubierre Metric defines the so-called warp drive spacetime. This is a Lorentzian manifold which, if interpreted in the context of general relativity, exhibits features reminiscent of the warp drive from Star Trek: a warp bubble appears in previously flat spacetime and moves off at effectively superluminal speed. Inhabitants of the bubble feel no inertial effects. The object(s) within the bubble are not moving (locally) faster than light, instead, the space around them shifts so that the object(s) arrives at its destination faster than light would in normal space.[2]

Alcubierre chose a specific form for the function f, but other choices give a simpler spacetime exhibiting the desired "warp drive" effects more clearly and simply.

[edit] Mathematics of the Alcubierre drive

Using the 3+1 formalism of general relativity, the spacetime is described by a foliation of space-like hypersurfaces of constant coordinate time t. The general form of the Alcubierre metric is:

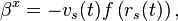

where α is the lapse function that gives the interval of proper time between nearby hypersurfaces, βi is the shift vector that relates the spatial coordinate systems on different hypersurfaces and γij is a positive definite metric on each of the hypersurfaces. The particular form that Alcubierre studied[1] is defined by:

where

and

with R > 0 and σ > 0 arbitrary parameters. Alcubierre's specific form of the metric can thus be written;

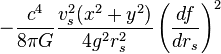

With this particular form of the metric, it can be shown that the energy density measured by observers whose 4-velocity is normal to the hypersurfaces is given by

where g is the determinant of the metric tensor. Thus, as the energy density is negative, one needs exotic matter to travel faster than the speed of light'.[1] The existence of exotic matter is not theoretically ruled out, the Casimir effect and the Accelerating Universe both lends support to the proposed existence of such matter. However, generating enough exotic matter and sustaining it to perform feats such as faster-than-light travel (and also to keep open the 'throat' of a wormhole) is thought to be impractical. Low has argued that within the context of general relativity, it is impossible to construct a warp drive in the absence of exotic matter.[3] It is generally believed that a consistent theory of quantum gravity will resolve such issues once and for all.

[edit] Physics of the Alcubierre drive

For those familiar with the effects of special relativity, such as Lorentz contraction and time dilation, the Alcubierre metric has some apparently peculiar aspects. In particular, Alcubierre has shown that even when the ship is accelerating, it travels on a free-fall geodesic. In other words, a ship using the warp to accelerate and decelerate is always in free fall, and the crew would experience no accelerational g-forces. Enormous tidal forces would be present near the edges of the flat-space volume because of the large space curvature there, but by suitable specification of the metric, these would be made very small within the volume occupied by the ship.[1]

The original warp drive metric, and simple variants of it, happen to have the ADM form which is often used in discussing the initial value formulation of general relativity. This may explain the widespread misconception that this spacetime is a solution of the field equation of general relativity. Metrics in ADM form are adapted to a certain family of inertial observers, but these observers are not really physically distinguished from other such families. Alcubierre interpreted his "warp bubble" in terms of a contraction of "space" ahead of the bubble and an expansion behind. But this interpretation might be misleading,[4] since the contraction and expansion actually refers to the relative motion of nearby members of the family of ADM observers.

In general relativity, one often first specifies a plausible distribution of matter and energy, and then finds the geometry of the spacetime associated with it; but it is also possible to run the Einstein field equations in the other direction, first specifying a metric and then finding the energy-momentum tensor associated with it, and this is what Alcubierre did in building his metric. This practice means that the solution can violate various energy conditions and require exotic matter. The need for exotic matter leads to questions about whether it is actually possible to find a way to distribute the matter in an initial spacetime which lacks a "warp bubble" in such a way that the bubble will be created at a later time. Yet another problem is that, according to Serguei Krasnikov,[5] it would be impossible to generate the bubble without being able to force the exotic matter to move at locally FTL speeds, which would require the existence of tachyons. Some methods have been suggested which would avoid the problem of tachyonic motion, but would probably generate a naked singularity at the front of the bubble.[6][7]

[edit] Difficulties

[edit] Building the road

Krasnikov proposed that, if tachyonic matter could not be found or used, then a solution might be to arrange for masses along the path of the vessel to be set in motion in such a way that the required field was produced. But in this case the Alcubierre Drive vessel is not able to go dashing around the galaxy at will. It is only able to travel routes which, like a railroad, have first been equipped with the necessary infrastructure.

The pilot inside the bubble is causally disconnected with its walls and cannot carry out any action outside the bubble. However, it is necessary to place devices along the route in advance and, since the pilot cannot do this while "in transit", the bubble cannot be used for the first trip to a distant star. In other words, to travel to Vega (which is 26 light-years from the Earth) one first has to arrange everything so that the bubble moving toward Vega with a superluminal velocity would appear and these arrangements will always take more than 26 years.[5]

[edit] It takes one to build one

Coule has argued that schemes such as the one proposed by Alcubierre are not feasible because the matter to be placed on the road beforehand has to be placed at superluminal speed. Thus, according to Coule, an Alcubierre Drive is required in order to build an Alcubierre Drive. Since none have been proven to exist already then the drive is impossible to construct, even if the metric is physically meaningful. Coule argues that an analogous objection will apply to any proposed method of constructing an Alcubierre Drive.[7]

[edit] Energy requirement

Significant problems with the metric of this form stem from the fact that all known warp drive spacetimes violate various energy conditions. It is true that certain experimentally verified quantum phenomena, such as the Casimir effect, when described in the context of the quantum field theories, lead to stress-energy tensors which also violate the energy conditions and so one might hope that Alcubierre type warp drives could perhaps be physically realized by clever engineering taking advantage of such quantum effects. However, if certain quantum inequalities conjectured by Ford and Roman hold,[8] then the energy requirements for some warp drives may be absurdly gigantic, e.g. the energy -1067gram equivalent might be required[9] to transport a small spaceship across the Milky Way galaxy. This is orders of magnitude greater than the mass of the universe. Counterarguments to these apparent problems have been offered,[2] but not everyone is convinced they can be overcome.

Chris Van Den Broeck, in 1999, has tried to address the potential issues.[10] By contracting the 3+1 dimensional surface area of the 'bubble' being transported by the drive, while at the same time expanding the 3 dimensional volume contained inside, Van Den Broeck was able to reduce the total energy needed to transport small atoms to less than 3 solar masses. Later, by slightly modifying the Van Den Broeck metric, Krasnikov reduced the necessary total amount of negative energy to a few milligrams.[2]

[edit] The Alcubierre drive and science fiction

Faster-than-light travel is often used in science fiction to denote a wide variety of imaginary propulsion methods, most of which have nothing to do with the Alcubierre drive or any other physical theory.

The physics of warp drive in Star Trek have never been defined specifically onscreen and none of the "technical manuals" based on the show has made any reference to Dr. Alcubierre's theory. However, in some peripheral Star Trek material, such as Aftermath by Christopher L. Bennett in the Starfleet Corps of Engineers Ebook series, there is an attempt to reconcile warp drive with the Alcubierre theory.[citation needed]

A more recent book called Warp Speed by Dr. Travis S. Taylor delves more into detail about the Alcubierre theory, as well as using it as the basis for the entire book.[citation needed]

Alcubierre drive theory is also mentioned in Orbiter, a graphic novel by Warren Ellis.

Stephen Baxter mentions Alcubierre drive theory in his short story collection Vacuum Diagrams.

Ian Douglas uses Alcubierre drive theory in his Inheritance Trilogy novels.

The hyperdrive on the starship Von Braun in System Shock 2 is based on Alcubierre drive theory and its ability to warp spacetime becomes a key plot point later in the game.[citation needed]

[edit] See also

- Exact solutions in general relativity (for more on the sense in which the Alcubierre spacetime is a solution).

- Spacecraft propulsion

- Faster-than-light

- Krasnikov Tube

[edit] References

- ^ a b c d Alcubierre, Miguel (1994). "The warp drive: hyper-fast travel within general relativity". Class. Quant. Grav. 11: L73–L77. doi:. See also the "eprint version". arXiv. http://www.arxiv.org/abs/gr-qc/0009013. Retrieved on 23 June 2005., and also at iop.org

- ^ a b c S. Krasnikov (2003). "The quantum inequalities do not forbid spacetime shortcuts". Physical Review D 67: 104013. doi:. See also the "eprint version". arXiv. http://www.arxiv.org/abs/gr-qc/0207057.

- ^ Low, Robert J. (1999). "Speed Limits in General Relativity". Class. Quant. Grav. 16: 543–549. doi:. See also the "eprint version". arXiv. http://www.arxiv.org/abs/gr-qc/9812067. Retrieved on 30 June 2005.

- ^ Natario, Jose (2002). "Warp drive with zero expansion". Class. Quant. Grav. 19: 1157–1166. doi:. See also the "eprint". arXiv. http://www.arxiv.org/abs/gr-qc/0110086. Retrieved on 23 June 2005.

- ^ a b S. Krasnikov (1998). "Hyper-fast travel in general relativity". Physical Review D 57: 4760. doi:. See also the "eprint version". arXiv. http://www.arxiv.org/abs/gr-qc/9511068.

- ^ Broeck, Chris Van Den, "On the (im)possibility of warpbubbles", 18 May 2000, See eprint,arXiv, retrieved 12 April 2008

- ^ a b Coule, D H, "No Warp Drive", Class Quantum Grav 15, 1998, pp2523-2537, retrieved[1] 12 April 2008

- ^ L. H. Ford and T. A. Roman (1996). "Quantum field theory constrains traversable wormhole geometries". Physical Review D 53: 5496. doi:. See also the "eprint". arXiv. http://www.arxiv.org/abs/gr-qc/9510071.

- ^ Pfenning, Michael J.; Ford, L. H. (1997). "The unphysical nature of 'Warp Drive'". Class. Quant. Grav. 14: 1743–1751. doi:. See also the "eprint". arXiv. http://www.arxiv.org/abs/gr-qc/9702026. Retrieved on 23 June 2005.

- ^ Broeck, Chris Van Den (1999). "A `warp drive' with more reasonable total energy requirements". Class. Quant. Grav. 16: 3973–3979. doi:. See also the "eprint". arXiv. http://www.arxiv.org/abs/gr-qc/9905084. Retrieved on 23 June 2005.

-

- Lobo, Francisco S. N.; & Visser, Matt (2004). "Fundamental limitations on 'warp drive' spacetimes". Class. Quant. Grav. 21: 5871–5892. doi:. See also the "eprint". arXiv. http://www.arxiv.org/abs/gr-qc/0406083. Retrieved on 23 June 2005.

- Hiscock, William A. (1997). "Quantum effects in the Alcubierre warp drive spacetime". Class. Quant. Grav. 14: L183–L188. doi:. See also the "eprint". arXiv. http://www.arxiv.org/abs/gr-qc/9707024. Retrieved on 23 June 2005.

- Berry, Adrian (1999). The Giant Leap: Mankind Heads for the Stars. Headline. ISBN 0-7472-7565-3. Apparently a popular book by a science writer, on space travel in general.

- T. S. Taylor, T. C. Powell, "Current Status of Metric Engineering with Implications for the Warp Drive," AIAA-2003-4991 39th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, Huntsville, Alabama, July 20-23, 2003

[edit] External links

- The Alcubierre Warp Drive by John G. Cramer

- The warp drive: hyper-fast travel within general relativity - Alcubierre's original paper (PDF File)

- Problems with Warp Drive Examined - (PDF File)

- Marcelo B. Ribeiro's Page on Warp Drive Theory

- A short video clip of the hypothetical effects of the warp drive.

- Doc Travis S. Taylor's website

- The (Im) Possibility of Warp Drive (Van Den Broeck)

- Reduced Energy Requirements for Warp Drive (Loup, Waite)

- Warp Drive Space-Time (González-Díaz)

- "Ideas Based On What We’d Like To Achieve". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/centers/glenn/technology/warp/ideachev_prt.htm. It describes the concept in laymans terms