Columbia University

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Columbia University in the City of New York | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| Motto: | In lumine Tuo videbimus lumen (Latin) |

| Motto in English: | In Thy light shall we see light (Psalm 36:9) |

| Established: | 1754 |

| Type: | Private |

| Endowment: | US $7.15 Billion[1] |

| President: | Lee C. Bollinger |

| Faculty: | 3,543[2] |

| Students: | 24,820[3] |

| Undergraduates: | 6,923[3] |

| Postgraduates: | 15,731[3] |

| Location: | |

| Campus: | Total, 299 acres (1.23 km²): Urban, 36 acres (0.15 km²) Morningside Heights Campus, 26 acres (0.1 km²), Baker Field athletic complex, 20 acres (0.09 km²), Medical Center, 157 acres (0.64 km²) Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, 60 acres (0.25 km²), Nevis Laboratories, Reid Hall (Paris) |

| Former names: | *King's College (1754-1784) *Columbia College (1784-1896) |

| Newspaper: | Columbia Daily Spectator |

| Colors: | Columbia blue and White |

| Nickname: | Columbia Lions |

| Athletics: | NCAA Division I FCS, Ivy League 29 sports teams |

| Affiliations: | MAISA; AAU |

| Website: | www.columbia.edu |

Columbia University in the City of New York (colloquially known as Columbia University), is a private university in the United States and a member of the Ivy League. Columbia's main campus lies in the Morningside Heights neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan, in New York City. The institution was established as King's College by the Church of England, receiving a Royal Charter in 1754 from George II of Great Britain. One of only two universities in the United States to have been founded by royal charter, it was the only college established in the Province of New York. It was the fifth college established in the Thirteen Colonies. After the American Revolutionary War, it was briefly chartered as a New York State entity from 1784-1787. The university now operates under a 1787 charter that places the institution under a private board of trustees.

Contents |

[edit] Campus

[edit] Morningside Heights

Most of Columbia's graduate and undergraduate studies are conducted in Morningside Heights on Seth Low's late-19th century vision of a university campus where all disciplines could be taught in one location. The campus was designed along Beaux-Arts principles by acclaimed architects McKim, Mead, and White and is considered one of their best works.

Columbia's main campus occupies more than six city blocks, or 32 acres (132,000 m²), in Morningside Heights, a neighborhood located between the Upper West Side and Harlem sections of Manhattan that contains a number of academic institutions. The university owns over 7,800 apartments in Morningside Heights, which house faculty, graduate students, and staff. Almost two dozen undergraduate dormitories (purpose-built or converted) are located on campus or in Morningside Heights.[4] Columbia University has an extensive underground tunnel system dating back more than a century, with the oldest portions existing even before the present campus was constructed. Some of these tunnels are open to students today, while others have been closed off to the public.

New buildings and structures on the campus, especially those built following the Second World War, have often only been constructed after a contentious process often involving open debate and community protest over the new structures. Often the complaints raised by protests during such periods of expansion have included issues beyond the debate over construction of design that diverged from the original McKim, Mead, and White plan. Protests often involved complaints against the administration of the university. This was the case with Uris Hall, which sits behind Low Library, built in the 1960s. It also applied to issues about the more recent Alfred Lerner Hall, a deconstructivist structure completed in 1998 and designed by Columbia's then-Dean of Architecture, Bernard Tschumi. These same issues have been reflected in the current debate over future expansion of the campus into Manhattanville, several blocks uptown from the current campus.[5]

Columbia's library system includes over 9.5 million volumes.[6]

One library of note on campus is the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, which is the largest library of architecture in the United States and among, if not the, largest in the world.[7] The library contains more than 400,000 volumes, of which most are non-circulating and must be read on site. One of the library's major undertakings is the "Avery Index to Architectural Periodicals", which is one of the foremost international resources for locating citations to architecture and related topics in periodical literature. The Avery Index covers periodicals thoroughly from prsent day back to the 1930s, with limited coverage dating to the nineteenth century.

Several buildings on the Morningside Heights campus are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Low Memorial Library, a National Historic Landmark and the centerpiece of the campus, is listed for its architectural significance. Philosophy Hall is listed as the site of the invention of FM radio. Also listed is Pupin Hall, another National Historic Landmark, which houses the physics and astronomy departments. Here the first experiments on the nuclear fission of uranium were conducted by Enrico Fermi. The uranium atom was split there ten days after the world's first atom-splitting in Copenhagen, Denmark.

[edit] Other campuses

Health-related schools are located at the Columbia University Medical Center, 20 acres (81,000 m2) located in the neighborhood of Washington Heights, fifty blocks uptown. Columbia also owns the 26-acre (110,000 m2) Baker Field, which includes the Lawrence A. Wien Stadium as well as facilities for field sports, outdoor track and tennis, at the northern tip of Manhattan island (in the neighborhood of Inwood). There is a third campus on the west bank of the Hudson River, the 157-acre (0.64 km2) Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, New York. A fourth is the 60-acre (240,000 m2) Nevis Laboratories in Irvington, New York. A satellite site in Paris holds classes at Reid Hall. The Arden House in Harriman, New York is primarily used for the Executive MBA Program.

[edit] University Hospital

New York-Presbyterian Hospital is affiliated with medical schools of both Columbia University and Cornell University. According to the US News and World Reports "Americas Best Hospitals 2007", it is ranked sixth overall and third among university hospitals. Columbia Medical School has a strategic partnership with New York State Psychiatric Institute. Columbia is also affiliated with nineteen hospitals in the US and four hospitals overseas.

[edit] Alma Mater

This name refers to a statue on the steps (see below) of Low Memorial Library by sculptor Daniel Chester French. There is a small owl "hidden" on the sculpture. Alma Mater is also the subject of many Columbia legends. The main legends include that the first student in the freshmen class to find the hidden owl on the statue will be valedictorian, and that any subsequent Barnard student who finds it will marry a Columbia man, seeing as how Barnard is a women's college.

[edit] Butler Library

The main library, packed during midterms and finals weeks, is composed of three main parts: the stacks, the study rooms, and the cafe. Students are known to leave their belongings as a placeholder for days on end, a few only leaving the library to sleep a few hours while others come and go as they please. During finals, to get a spot at Butler, students wake up early in the morning and compete with others for a seat. Some students are reported to have gone so far as to set up offices in disused sections of the library on the ninth floor. Butler houses 1.9 million of the university's 9.2 million volumes,[8] mostly in the humanities and history. Unlike the libraries of most other schools, Butler remains at least partially open 24 hours a day and acts as a center of late night studying. Butler also houses Columbia University's Rare Books and Manuscripts Library (including the Columbiana University Archives), the Philip L. Milstein Undergraduate Library, the Oral History collection, and the Butler Media Collection. Butler Library is one of two dozen libraries on campus, mostly distinguished by subject disciplines.[9]

[edit] Residence halls

First-year students usually live in one of the large residence halls situated around South Lawn: Hartley Hall, Wallach Hall (originally Livingston Hall), John Jay Hall, Furnald Hall or Carman Hall. The East Campus is another large on-campus residential complex. There are several dorms immediately off-campus, such as Hogan Hall, McBain Hall, Schapiro Hall, Broadway Hall, Wien Hall and a variety of smaller buildings. Barnard College also has dorms on its campus.

[edit] The Steps

"The Steps", alternatively known as "Low Steps" or the "Urban Beach", are a popular meeting area and hangout for Columbia students. The term refers to the long series of granite steps leading from the lower part of campus (South Field) to its upper terrace, atop which sits Low Memorial Library, as well as adjacent areas, including Low Plaza and small nearby lawns. On warm days, particularly in the spring, the steps become crowded with students conversing, reading, or sunbathing. Occasionally, they play host to film screenings and concerts. The King's Crown Shakespeare Troupe annually performs an outdoor play on the steps. The design of the steps is modeled after the architecture in Raphael's "The School of Athens," a fresco in the Vatican.

[edit] Sundial

This elevated stone pedestal at the center of the main campus quadrangle now serves as a podest for various speeches. Originally there was a large granite sphere located upon the pedestal, which would mark the time via its shadow. It sat upon the pedestal from approximately 1914 to 1946. It was removed in that year due to cracks that formed within it. The ball was assumed destroyed for 55 years until it was discovered intact in a Michigan field in 2001. As of 2006, it seems unlikely that the sundial will ever be restored to a working state.[10]

[edit] History

Columbia is the oldest institution of higher education in the state of New York. Founded and chartered as King's College in 1754, Columbia is the sixth-oldest such institution in the United States (by date of founding; fifth by date of chartering). After the American Revolutionary War, King's College was renamed Columbia College in 1784, and in 1896 it was further renamed Columbia University. Columbia has grown over time to encompass twenty schools and affiliated institutions.

[edit] King's College: 1754–1784

Discussions regarding the foundation of a college in the Province of New York began as early as 1704, but serious consideration of such proposals was not entertained until the early 1750s, when local graduates of Yale and members of the congregation of Trinity Church (then Church of England, now Episcopal) in New York City became alarmed by the establishment of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). Concerns arose both because it was founded by "new-light" Presbyterians influenced by the evangelical Great Awakening and, as it was located in the province just across the Hudson River, because it provoked fears of New York developing a cultural and intellectual inferiority. They established their own 'rival' institution, King's College, and elected as its first president Samuel Johnson. Classes began on July 17, 1754 in Trinity Church yard, with Johnson as the sole faculty member. A few months later, on October 31, 1754, Great Britain's King George II officially granted a royal charter for the college. In 1760, King's College moved to its own building at Park Place, near the present City Hall, and in 1767 it established the first American medical school to grant the M.D. degree.

Controversy surrounded the founding of the new college in New York, as it was a thoroughly Church of England institution dominated by the influence of Crown officials in its governing body, such as the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Crown Secretary for Plantations and Colonies. Fears of the establishment of a Church of England episcopacy and of Crown influence in America through King's College were underpinned by its vast wealth, far surpassing all other colonial colleges of the period.[11]

The American Revolution and the subsequent war were catastrophic for King's College. It suspended instruction in 1776, and remained so for eight years, beginning with the arrival of the Continental Army in the spring of that year and continuing with the military occupation of New York City by British troops until their departure in 1783. The college's library was looted and its sole building requisitioned for use as a military hospital first by American and then British forces.[12][13] Additionally, many of the college's alumni, primarily Loyalists, fled to Canada or Great Britain in the war's aftermath, leaving its future governance and financial status in question.

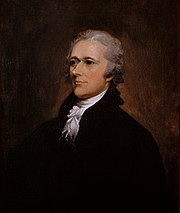

Although the college had been considered a bastion of Tory sentiment, it nevertheless produced many key leaders of the Revolutionary generation - individuals later instrumental in the college's revival. Among the earliest students and trustees of King's College were five "founding fathers" of the United States: John Jay, who negotiated the Treaty of Paris between the United States and Great Britain, ending the Revolutionary War, and who later became the first Chief Justice of the United States; Alexander Hamilton, military aide to General George Washington, author of most of the Federalist Papers, and the first Secretary of the Treasury; Gouverneur Morris, the author of the final draft of the United States Constitution; and Robert R. Livingston, a member of the Committee of Five that drafted the Declaration of Independence.

Hamilton's first experience with the military came while a student during the summer of 1775, after the outbreak of fighting at Boston. Along with Nicholas Fish, Robert Troup, and a group of other students from King's he joined a volunteer militia company called the "Hearts of Oak" – Hamilton achieving the rank of Lieutenant. They adopted distinctive uniforms, complete with the words "Liberty or Death" on their hatbands, and drilled under the watchful eye of a former British officer in the graveyard of the nearby St. Paul's Chapel. In August 1775, while under fire from the HMS Asia, the Hearts of Oak (a.k.a. the "Corsicans") participated in a successful raid to seize cannon from the Battery, becoming an artillery unit thereafter.[14] Ironically, in 1776 Captain Hamilton would engage in and survive the Battle of Harlem Heights, which took place on and around the site that would become home to his Alma Mater over a century later, only to be - after his dueling death twenty-eight years later - entombed on the site of the first home for King's College in the Trinity Church yard.

[edit] Early Columbia College: 1784–1857

After the war, the remaining members of the Board of Governors of King’s sought to resuscitate the college, petitioning the Legislature of New York to “make such alterations in the Charter as the changed condition of affairs might demand.” The Legislature agreed, and on May 1, 1784, it passed “an Act for granting certain privileges to the College heretofore called King’s College.” [15] The Act created a Board of Regents to oversee the resuscitation of King’s, giving them the power to hire a college president and appoint professors, but prohibiting the College from administering any “religious test-oath” to its faculty. Finally, in an effort to demonstrate its support for the new Republic, the Legislature stipulated that “the College within the City of New York heretofore called King’s College be forever hereafter called and known by the name of Columbia College.” [15]

On May 5, 1784, the Regents held their first meeting, instructing Treasurer Brockholst Livingston and Secretary Robert Harpur (who was Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy at King’s) to recover the books, records and any other assets that had been dispersed during the war, and appointing a committee to supervise the repairs of the college building. In addition, the Regents moved quickly to rebuild Columbia’s faculty, appointing William Cochran instructor of Greek and Latin. [15]

In the summer of 1784, after the legislature passed the act restoring the college, Major General James Clinton, a hero of the revolutionary war, brought his son DeWitt Clinton to New York on his way to enroll him as a student at the College of New Jersey. When James Duane, the Mayor of New York and a member of the Regents, heard that the younger Clinton was leaving the state for his education, he pleaded with Cochran to offer him admission to the reconstituted Columbia. Cochran agreed - in no small part due to the fact that DeWitt’s uncle, George Clinton, the Governor of New York, had recently been elected Chancellor of the College by the Regents - and DeWitt Clinton became one of nine students admitted to Columbia that year. [15]

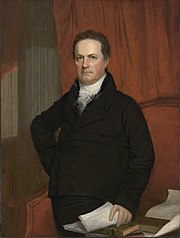

As the state proved negligent in its funding of the institution, this arrangement became increasingly unsatisfactory for both. An expansion of the Regents to 20 New York City residents had placed Hamilton and Jay at the helm, and they, along with Duane, argued for privatization of the college. In 1787 a new charter was adopted for the college, still in use today, granting power to a private board of Trustees. Samuel Johnson's son, William Samuel Johnson, became its president.

For a period in the 1790s, with New York City as the federal and state capital and the country under successive Federalist governments, a revived Columbia thrived under the auspices of Federalists such as Hamilton and Jay. George Washington, notably, attended the commencement of 1790, and nascent interest in legal education commenced under Professor James Kent. As the state and country transitioned to a considerably more Jeffersonian era, however, the college's good fortunes began to dry up. The primary difficulty was funding; the college, already receiving less from the state following its privatization, was beset with even more financial difficulties as hostile politicians took power and as new upstate colleges, particularly Hamilton and Union, lobbied effectively for subsidies. What Columbia did receive was Manhattan real estate, which would only later prove lucrative.

Columbia's performance flagged for the remainder of the 19th century's first half. The law faculty never managed to thrive during this period, and in 1807 the medical school, hoping to arrest its decline, broke off to merge with the independent College of Physicians and Surgeons. Contention between students and faculty were highlighted by the "Riotous Commencement" of 1811, in which students violently protested the faculty's decision not to confer a degree upon John Stevenson, who had inserted objectionable words into his commencement speech. Though the college was finally able to shake its embarrassing reputation for structural shabbiness by adding several wings to College Hall and refinishing it in the more fashionable Greek Revival style, the effort failed to halt Columbia's long-term downturn, and was soon overshadowed by the Gibbs Affair of 1854, in which famed chemistry professor Oliver Wolcott Gibbs was denied a professorship at the college, from which he had graduated, due to his Unitarian affiliation. The event demonstrated to many, including frustrated diarist and trustee George Templeton Strong, the narrow-mindedness of the institution. By July, 1854 the Christian Examiner of Boston, in an article entitled "The Recent Difficulties at Columbia College", noted that the school was "good in classics" yet "weak in sciences", and had "very few distinguished graduates".[16]

[edit] Expansion and the move to Madison Avenue

In 1857, the College moved from Park Place to a primarily Gothic Revival campus on 49th Street and Madison Avenue, where it remained for the next fifty years. The transition to the new campus coincided with a new outlook for the college; during the commencement of that year, College President Charles King proclaimed Columbia "a university". During the last half of the nineteenth century, under the leadership of President F.A.P. Barnard, the institution rapidly assumed the shape of a true modern university. Columbia Law School was founded in 1858, and in 1864 the School of Mines, the country's first such institution and the precursor to today's Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science, was established. Barnard College for women, established by the eponymous Columbia president, was established in 1889; the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons came under the aegis of the University in 1891, followed by Teachers College, Columbia University in 1893. The Graduate Faculties in Political Science, Philosophy, and Pure Science awarded its first PhD in 1875.[16][17] This period also witnessed the inauguration of Columbia's participation in intercollegiate sports, with the creation of the baseball team in 1867, the organization to the football team in 1870, and the creation of a crew team by 1873. The first intercollegiate Columbia football game was a 6-3 loss to Rutgers. The Columbia Daily Spectator began publication during this period as well, in 1877.[18]

[edit] Morningside Heights

In 1896, the trustees officially authorized the use of yet another new name, Columbia University, and today the institution is officially known as "Columbia University in the City of New York." Additionally, the engineering school was renamed the "School of Mines, Engineering and Chemistry." At the same time, University president Seth Low moved the campus again, from 49th Street to its present location, a more spacious (and, at the time, more rural) campus in the developing neighborhood of Morningside Heights. The site was formerly occupied by the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum. One of the asylum's buildings, the warden's cottage (later known as East Hall and Buell Hall), is still standing today.

The building often depicted as emblematic of Columbia is the centerpiece of the Morningside Heights campus, Low Memorial Library. Constructed in 1895, the building is still referred to as "Low Library" although it has not functioned as a library since 1934. It currently houses the offices of the President and Provost, the Visitor's Center, the Trustees' Room and Columbia Security. Patterned on several precursors, including the Parthenon and the Pantheon, it is surmounted by the largest all-granite dome in the United States.[19]

Under the leadership of Low's successor, Nicholas Murray Butler, Columbia rapidly became the nation's major institution for research, setting the "multiversity" model that later universities would adopt. On the Morningside Heights campus, Columbia centralized on a single campus the College, the School of Law, the Graduate Faculties, the School of Mines (predecessor of the Engineering School), and the College of Physicians & Surgeons. Butler went on to serve as president of Columbia for over four decades and became a giant in American public life (as one-time vice presidential candidate and a Nobel Laureate). His introduction of "downtown" business practices in university administration led to innovations in internal reforms such as the centralization of academic affairs, the direct appointment of registrars, deans, provosts, and secretaries, as well as the formation of a professionalized university bureaucracy, unprecedented among American universities at the time.

In 1893 the Columbia University Press was founded in order to "promote the study of economic, historical, literary, scientific and other subjects; and to promote and encourage the publication of literary works embodying original research in such subjects." Among its publications are The Columbia Encyclopedia, first published in 1935, and The Columbia Lippincott Gazetteer of the World, first published in 1952.

In 1902, New York newspaper magnate Joseph Pulitzer donated a substantial sum to the University for the founding of a school to teach journalism. The result was the 1912 opening of the Graduate School of Journalism — the only journalism school in the Ivy League. The school is the administrator of the Pulitzer Prize and the duPont-Columbia Award in broadcast journalism.

In 1904 Columbia organized adult education classes into a formal program called Extension Teaching (later renamed University Extension). Courses in Extension Teaching eventually give rise to the Columbia Writing Program, the Columbia Business School, and the School of Dentistry and Oral Surgery.

Columbia Business School was added in the early 20th century. During the first half of the 20th Century Columbia and Harvard had the largest endowments in the US.

By the late 1930s, a Columbia student could study with the likes of Jacques Barzun, Paul Lazarsfeld, Mark Van Doren, Lionel Trilling, and I. I. Rabi. The University's graduates during this time were equally accomplished — for example, two alumni of Columbia's Law School, Charles Evans Hughes and Harlan Fiske Stone (who also held the position of Law School dean), served successively as Chief Justices of the United States. Dwight Eisenhower served as Columbia's president from 1948 until he became the President of the United States in 1953.

Research into the atom by faculty members John R. Dunning, I. I. Rabi, Enrico Fermi and Polykarp Kusch placed Columbia's Physics Department in the international spotlight in the 1940s after the first nuclear pile was built to start what became the Manhattan Project.[20]

Following the end of World War II, the School of International Affairs was founded in 1946. Focusing on developing diplomats and foreign affairs specialists, the school began by offering the Master of International Affairs. To satisfy an increasing desire for skilled public service professionals at home and abroad, the School added the Master of Public Administration degree in 1977. In 1981 the School was renamed the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA). The School introduced an MPA in Environmental Science and Policy in 2001 and, in 2004, SIPA inaugurated its first doctoral program — the interdisciplinary Ph.D. in Sustainable Development.

In 1947, to meet the needs of GIs returning from World War II, University Extension was reorganized as an undergraduate college and designated the Columbia University School of General Studies. While the former university extension had granted the B.S. degree since 1921, the School of General Studies first granted the B.A. degree in 1968 and is now considered one of the four colleges of Columbia University (CC,BC,SEAS,GS).

Columbia College first admitted women in the fall of 1983, after a decade of failed negotiations with Barnard College, an all female institution affiliated with the University, to merge the two schools. Barnard College still remains affiliated with Columbia. All Barnard graduates are issued diplomas authorized by both Columbia and Barnard.

In 1990 the Faculty of Arts & Sciences was created, unifying the faculties of Columbia College, the School of General Studies, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and the School of International and Public Affairs.

In 1997, the Columbia Engineering School was renamed the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science, in honor of Chinese businessman Z. Y. Fu, who gave Columbia $26 million. The school is popularly referred to as "SEAS" or simply "the engineering school."

[edit] Manhattanville

As of April 2007, the university had purchased more than two-thirds of 17 acres (69,000 m2) desired for a new campus in Manhattanville, to the north of the Morningside Heights campus. Stretching from 125th Street to 133rd Street, the new campus would house buildings for Columbia's schools of business and the arts and allow the construction of the Jerome L. Greene Center for Mind, Brain, and Behavior, where research will occur on neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's. [21] The $7 billion expansion plan includes demolishing all buildings, except three that are historically significant, eliminating the existing light industry and storage warehouses, and relocating tenants in 132 apartments. Replacing these buildings will be 6,800,000 square feet (632,000 m2) of space for the University. The space will be used for additional teaching, critical research, and auxiliary services. Designed by Pritzker prize winning architect Renzo Piano, the 17 acres (69,000 m2) will include more accessible pedestrian streets and additional public open spaces.

According to the Environmental Impact Statement recently certified by the Department of City Planning, almost 300 people would be displaced from the project zone, and almost 3,300 would be displaced from areas surrounding it. Community activist groups in West Harlem are fighting the expansion for reasons ranging from property protection and fair exchange for land, to residents' rights and care of their collective voice.[22] Despite dissent at a series of public hearings, the City Council of New York approved Columbia's Manhattanville expansion plan on December 19, 2007, having received strong support from Councilman Robert Jackson (D-West Harlem) and Councilwoman Inez Dickens (D-Central Harlem). Critics accuse the University of having used its political muscle to silence dissent, though dissent was heard at public hearings. At least one landowner claims to have been "threatened" by university representatives. [2] Negotiations with other landowners have been successful, one example being the trade of land from Manhattanville to a block of land in Washington Heights. [3] Most recently, as of December 2008, the State of New York's Empire State Development Corporation approved use of Eminent Domain, which, through declaration of Manhattanville's "blighted" status, gives governmental bodies the right to appropriate private property for public use [4]. This makes certain the future of Columbia's campus expansion into Manhattanville.

[edit] Academics

[edit] Admissions and financial aid

In 2008, Columbia College admitted 8.7% of applicants for the Class of 2012, one of the lowest rates in the country.[23] The Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Sciences admitted 17.6%, a record for the School.[23]

Columbia is also a diverse school, with approximately 49% of all students identifying themselves as persons of color. Additionally, over 50% of all undergraduates in the Class of 2011 will be receiving financial aid. The average financial aid package for these students exceeds $27,000, with an average grant size of over $20,000.[23]

On April 11, 2007, Columbia University announced a $400m to $600m donation from media billionaire alumnus John Kluge[24] to be used exclusively for undergraduate financial aid. The donation is among the largest single gifts to higher education. Its exact value will depend on the eventual value of Kluge's estate at the time of his death; however, the generous donation has helped change financial aid policy at Columbia. The University was able to extend financial aid offerings to more students; Columbia now has one of the most comprehensive financial aid policies [5].

Undergraduate students in Columbia College and the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science with family income under $60,000 are not expected to pay tuition, room, board, and other fees. At the same time, all students who are eligible for financial aid (regardless of income), in lieu of loans, will be awarded University grants.

[edit] Organization

Columbia has three undergraduate institutions:

- Columbia College (CC): the liberal arts college, offering the Bachelor of Arts degree

- The Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science (SEAS): the engineering and applied science school, offering the Bachelor of Science degree

- The School of General Studies (GS): offers Bachelor of Arts degrees to students who have chosen non-traditional paths in their education

Columbia also has a number of graduate and professional schools, including:

- Columbia Law School (CLS): offers the LLM, JD, and JSD degrees

- Columbia Business School (CBS): offers the MBA and PhD degrees

- Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons (P&S): offers the MD degree

- Columbia University College of Dental Medicine: offers the DDS degree

- School of Nursing: offers the BS, MS, and PhD degrees

- Mailman School of Public Health: offers the MPH, DrPH, and Ph.D degrees

- Graduate School of Journalism (J-School or CJS): founded by Joseph Pulitzer, offers the MA, MS, and PhD degrees

- School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA): offers MIA, MPA, PEPM, EMPA, and PhD degrees

- The Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP): offers the MArch, MS, and PhD degrees

- Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS): offers the MA, MS, and PhD degrees

- The School of the Arts (SoA): offers the MfA degree in four disciplines (film, theater, visual arts, and writing)

- Columbia University School of Social Work: offers the MS and PhD degrees

- The Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science (SEAS): in addition to undergraduate studies, students may also pursue MS and PhD degree programs in engineering.

- Columbia University's School of Continuing Education offers classes for non-matriculated elective course students, Master of Science Degrees, Post-baccalaureate Certificates, English Language Programs, Overseas Programs, Summer Session, and High School Programs.

The university is affiliated with Barnard College, Teachers College, the Union Theological Seminary, and the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, all located nearby in Morningside Heights. A joint undergraduate program is available through the Jewish Theological Seminary of America as well as through the Juilliard School.[25]

[edit] Rankings

| ARWU World[26] | 7th |

|---|---|

| ARWU National[27] | 6th |

| ARWU Natural Science & Math[28] | 12th |

| ARWU Engineering & CS[29] | 43rd |

| ARWU Life Sciences[30] | 7th |

| ARWU Clinical Medicine[31] | 5th |

| ARWU Social Sciences[32] | 3rd |

| CMUP[33] | 1st |

| THES World[34] | 10th |

| USNWR National University[35] | 8th |

| USNWR Business[36] | 9th |

| USNWR Law[37] | 4th |

| USNWR Medical (research) [38] | 11th |

| USNWR Medical (primary care) [39] | 58th |

| USNWR Engineering[40] | 21st |

| USNWR Education[41] | 4th |

| Washington Monthly National University[42] | 41st |

| Forbes[43] | 9th |

The undergraduate school of Columbia University is ranked 8th (tied with University of Chicago and Duke University) among national universities by U.S. News and World Report (USNWR),[44] 7th among world universities and 6th among universities in the Americas by Shanghai Jiao Tong University,[45] 9th by Forbes, 10th in the top 50 for Social Sciences[46],10th among world universities and 6th in North America by the THES - QS World University Rankings,[47] 10th among "global universities" by Newsweek,[48] and 1st in the U.S. among both national research universities by the Center for Measuring University Performance.[49] According to the National Research Council, graduate programs are ranked 8th nationally.[citation needed]

According to the U.S. News & World Report,[50]The Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, home to the Pulitzer Prize, ranks #1. Teachers College (Columbia's Graduate School of Education) ranks #4. School of Social Work ranks #4. The Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP) ranks #3, according to Architect magazine's November 2007 issue. Columbia Law School ranks #4. The Mailman School of Public Health ranks #6. Columbia Business School ranks #9, #2 according to The Financial Times, and #6 according to Fortune Magazine). Columbia's medical school, called the College of Physicians and Surgeons, ranks #11. According to Foreign Policy magazine, the School of International & Public Affairs (SIPA) PhD program (overall) in international relations is ranked #2, and the Master's program (policy area) is ranked #5. Finally, Columbia's Institute of Human Nutrition ranks #1, according to The Chronicle for Higher Education.

[edit] High School Programs

Columbia University's Summer Program for High School Students offers highly motivated students the opportunity of classes in the summer. The Summer Programs for High School Students in New York City, Barcelona, and the Middle East are renowned for their academic rigor and instructional excellence.

Columbia also offers a program called the Columbia University Science Honors Program, which attracts high school students (sophomores, juniors, and seniors). The program is highly competitive, admitting about one-sixth of applicants who are selected based on their transcripts, student-written essays, a teacher recommendation, and a three-hour science and math test. It offers college-level courses in science and math every Saturday during the academic year.

[edit] Student life

[edit] Publications

Columbia University is home to a rich diversity of undergraduate, graduate, and professional publications.

The Columbia Daily Spectator is the nation's second-oldest student newspaper;[51] and The Blue and White,[52] a monthly literary magazine established in 1890, has recently begun to delve into campus life and local politics in print and on its daily blog, dubbed the Bwog.

Political publications include The Current ,[53] a journal of politics, culture and Jewish Affairs; the Columbia Political Review,[54] the multi-partisan political magazine of the Columbia Political Union; and AdHoc,[55] which denotes itself as the "progressive" campus magazine and deals largely with local political issues and arts events.

Arts and literary publications include the Columbia Review,[56] the nation's oldest college literary magazine; the Columbia Journal of Literary Criticism;[57] and The Mobius Strip, [58] an online arts and literary magazine.

Columbia is home to numerous undergraduate academic publications. The Journal of Politics & Society,[59] is a journal of undergraduate research in the social sciences, published and distributed nationally by the Helvidius Group; the Columbia East Asian Review allows undergraduates throughout the world to publish original work on China, Japan, Korea, Tibet, and Vietnam and is supported by the Weatherhead East Asian Institute; and The Birch,[60] is an undergraduate journal of Eastern European and Eurasian culture that is the first national student-run journal of its kind; and the Columbia Science Review is a science magazine that prints general interest articles, faculty profiles, and student research papers.

The Fed [61] a triweekly satire and investigative newspaper; and the Jester of Columbia, [62] the newly (and frequently) revived campus humor magazine both inject humor into local life.

Other publications include The Columbian, the second oldest collegiate yearbook in the nation; the Gadfly, a biannual journal of popular philosophy produced by undergraduates; and Rhapsody in Blue, an undergraduate urban studies magazine.

Professional journals published by academic departments at Columbia University include Current Musicology[63] and The Journal of Philosophy.[64] During the spring semester, graduate students in the Journalism School publish The Bronx Beat, a bi-weekly newspaper covering the South Bronx.

[edit] Broadcasting

Columbia is home to two pioneers in undergraduate student broadcasting, WKCR-FM and CTV.

WKCR, the student run radio station broadcasts to the Tri-State area and claims to be the oldest FM radio station in the world, owing to the University's affiliation with Major Edwin Armstrong. The station currently has its studios on the second floor of Alfred Lerner Hall on the Morningside campus with its main transmitter tower at 4 Times Square in Midtown Manhattan.

Columbia Television (CTV)[65] is the nation's second oldest student television station and home of CTV News,[66] a weekly live news program produced by undergraduate students. CTV transmits a cablecast and webcast from its studio in Alfred Lerner Hall.

[edit] Speech and debate

The Philolexian Society is a literary and debating club founded in 1802, making it the oldest student group at Columbia, as well as the third oldest collegiate literary society in the country. It has many famous alumni, and administers the Joyce Kilmer Bad Poetry Contest (see below).

The Columbia Parliamentary Debate Team,[67] competes in tournaments around the country as part of the American Parliamentary Debate Association, and hosts both high school and college tournaments on Columbia's campus, as well as public debates on issues affecting the university.

[edit] Greek life

Columbia University is home to many fraternities, sororities, and co-educational Greek organizations. Approximately 10–15% of undergraduate students are associated with Greek life.[68] There has been a Greek presence on campus since the establishment in 1842 of the Lambda Chapter of Psi Upsilon. Today, there are thirteen NIC fraternities on the campus, four NPC sororities five multicultural Greek organizations, and five historically Black Fraternity and Sororities.[citation needed]

[edit] Entrepreneurship at Columbia

The Columbia University Organization of Rising Entrepreneurs (CORE) was founded in 1999. The student-run group aims to foster entrepreneurship on campus. Each year CORE hosts dozens of events, including a business plan competition and a series of seminars. Recent seminar speakers include Mark Cuban, owner of the Dallas Mavericks and Chairman of HDNet, and Blake Ross, creator of Mozilla Firefox. As of 2006, CORE has awarded graduate and undergraduate students with over $100,000 in seed capital. Events are possible through the contributions of various private and corporate groups; previous sponsors include Deloitte & Touche, Citigroup, and i-Compass.

There are currently over 2,000 members in CORE. The organization is governed by its executive board, which comprises fifteen undergraduates.

[edit] Other

The Columbia University Orchestra was founded by composer Edward MacDowell in 1896, and is the oldest continually operating university orchestra in the United States.[69] Undergraduate student composers at Columbia may choose to become involved with Columbia New Music, which sponsors concerts of music written by undergraduate students from all of Columbia's schools.

There are a number of performing arts groups at Columbia dedicated to producing student theater, including the Columbia Players, King's Crown Shakespeare Troupe (KCST), Columbia Musical Theater Society (CMTS), New and Original Material Authored by Students (NOMADS), Columbia University Performing Arts League (CUPAL), Black Theatre Ensemble (BTE), sketch comedy group Chowdah, and improvisational troupes Fruit Paunch and Sweeps.

The Columbia Queer Alliance is the central Columbia student organization that represents the lesbian, gay, transgender, and questioning student population. It is the oldest gay student organization in the world, founded as the Student Homophile League in 1966 by students including lifelong activist Stephen Donaldson.[70]

Columbia University campus military groups include the U.S. Military Veterans of Columbia University and Advocates for Columbia ROTC. In the 2005-06 academic year, the Columbia Military Society, Columbia's student group for ROTC cadets and Marine officer candidates, was renamed the Hamilton Society for "students who aspire to serve their nation through the military in the tradition of Alexander Hamilton". (Hamilton served with George Washington during the American Revolution.)

[edit] Athletics

A member institution of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, Columbia fields varsity teams in 29 sports. The football Lions play home games at the 17,000-seat Lawrence A. Wien Stadium at Baker Field. One hundred blocks north of the main campus at Morningside Heights, the Baker Athletics Complex also includes facilities for baseball, softball, soccer, lacrosse, field hockey, tennis, track and rowing. The basketball, fencing, swimming & diving, volleyball and wrestling programs are based at the Dodge Physical Fitness Center on the main campus.

The Columbia mascot is a lion named Roar-ee. At football games, the Columbia University Marching Band plays "Roar, Lion, Roar" each time the team scores and "Who Owns New York?" with each first down. At halftime, alumni stand and sing the alma mater, "Sans Souci." Notable among a number of songs commonly played and sung at various events such as commencement and convocation, and athletic games are: Colossus Of Columbia the Columbia University fight song.

Columbia became the third school in the United States to play intercollegiate football when it sent a squad to New Brunswick, N.J., in 1870 to play a team from Rutgers. Three years later, Columbia students joined representatives from Princeton, Rutgers and Yale to ratify the first set of rules to govern intercollegiate play.

During the first half of the 20th century, the Lions had consistent success on the gridiron. Under Hall of Fame coach Lou Little, the 1934 squad shut out heavily favored Stanford in the Rose Bowl winning what was the precursor to the national championship. During World War II football players were recruited to move uranium in support of the school's participation in the Manhattan Project. [71] Little’s 1947 edition beat defending national champion Army, then riding a 32-game win streak, in one of the most stunning upsets of the century. Greats of the era included the All-American Sid Luckman, the quarterback who would lead the Chicago Bears to four NFL championships in the 1940s while ushering football into the modern era with the T formation.

Since sharing their only Ivy League title with Harvard in 1961, the football Lions have had only three winning seasons (6-3 in 1971, 5-4-1 in 1994 and 8-2 in 1996). Norries Wilson, a runner-up for national assistant coach of the year while at the University of Connecticut in 2004, is the latest head coach brought in to try to turn the program around. Several Lions players have gone on to success in the National Football league in the past few decades, including quarterback John Witkowski, offensive lineman George Starke, and linebacker Marcellus Wiley.

The Lions boast a rich athletic tradition. The wrestling team is the oldest in the nation, and the football team was the third to join intercollegiate play. A Columbia crew was the first from outside Britain to win at the Henley Royal Regatta. Former students include baseball Hall of Famers Lou Gehrig and Eddie Collins and football Hall of Famer Sid Luckman.

More recently, Columbia has excelled at archery, cross country, fencing and wrestling. In 2008, Olympic silver medal fencer James L. Williams along with three teammates, including Keeth Smart, Class of 2010 at Columbia Business School, earned the first American medal in men's fencing since 1984. In 2000, Olympic gold medal swimmer Cristina Teuscher became the first Ivy League student to win the Honda-Broderick Cup, awarded to the best collegiate woman athlete in the nation. In 2007, the Men's Track Team captured the 4x800 Penn Relay's victory. This was the first time an Ivy League school won this race since 1974.

The baseball team hosted the first sporting event ever televised in the United States. On May 17, 1939 fledgling NBC broadcast a doubleheader between the Columbia Lions vs. Princeton Tigers at Columbia's Baker Field.[72]

In basketball, perhaps the greatest player to wear Columbia Blue was All-American Chet Forte, the 1957 national college player of the year. George Gregory, Jr. became the first African-American All-American in 1931. The 1968 Ivy League championship team included future NBA player Jim McMillian.

[edit] Controversies and student demonstrations

| This article's Criticism or Controversy section(s) may mean the article does not present a neutral point of view of the subject. It may be better to integrate the material in such sections into the article as a whole. (January 2009) |

[edit] Protests of 1968

Students initiated a major demonstration in 1968 over two major issues. The first was Columbia's proposed gymnasium in neighboring Morningside Park; this was seen by the protesters to be an act of aggression aimed at the black residents of neighboring Harlem. A second issue was the Columbia administration's failure to resign its institutional membership in the Pentagon's weapons research think-tank, the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA). Students barricaded themselves inside Low Library, Hamilton Hall, and several other university buildings during the protests, and New York City police were called onto the campus to arrest or forcibly remove the students.[73][74]

[edit] Protests against racism and apartheid

Further student protests, including hunger strike and more barricades of Hamilton Hall and the Business School [75] during the late 1970s and early 1980s, were aimed at convincing the university trustees to divest all of the university's investments in companies that were seen as active or tacit supporters of the apartheid regime in South Africa. A notable upsurge in the protests occurred in 1978, when following a celebration of the tenth anniversary of the student uprising in 1968,students marched and rallied in protest of University investments in South Africa. The Committee Against Investment in South Africa (CAISA) and numerous student groups including the Socialist Action Committee, the Black Student Organization and the Gay Students group joined together and succeeded in pressing for the first partial divestment of a U.S. University.

The initial (and partial) Columbia divestment, [76] focused largely on bonds and financial institutions directly involved with the South African regime.[77] It followed a year long campaign first initiated by students who had worked together to block the appointment of former Seceratary of State Henry Kissinger to an endowed chair at the University in 1977.[78]

Broadly backed by a diverse array of student groups and many notable faculty members the Committee Against Investment in South Africa held numerous teach-ins and demonstrations through the year focused on the trustees ties to the corporations doing business with South Africa. Trustee meetings were picketed and interrupted by demonstrations culminating in May 1978 in the takeover of the Graduate School of Business.[79][80] These initial successes set a pattern which was later repeated at many more campuses across the country, resulting in the eventual divestment at hundreds of colleges and universities.[citation needed]

[edit] Mahmoud Ahmadinejad visit and speech controversy

| Wikinews has related news: Protests mark Ahmadinejad's visit to Columbia University |

The School of International and Public Affairs traditionally extends invitations to many heads of state and heads of government who come to New York City for the opening of the fall session of the United Nations General Assembly. In 2007, Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was one of those invited to speak on campus. Ahmadinejad accepted his invitation and spoke on September 24, 2007 as part of Columbia University's World Leaders Forum.[81] The invitation proved to be highly controversial. Thousands of demonstrators swarmed the campus on September 24 and the speech itself was televised worldwide. University President Lee Bollinger tried to triangulate the controversy by letting Ahmadenijad speak, but with a extraordinarily negative introduction (given personally by Bollinger.) This did not mollify those who were displeased with the fact that the Iranian leader had been invited onto the campus. [82]

During his speech, Ahmadinejad criticized Israel's policies towards the Palestinians; called for research on the historical accuracy of Holocaust; raised questions as to who initiated the 9/11 attacks; expressed the self-determination of Iran's nuclear power program, criticizing the United Nation's policy of sanctions on his country; and criticized U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East. In response to a question about Iran's treatment of women and homosexuals, he asserted that women are respected in Iran and that "In Iran, we don't have homosexuals like in your country... In Iran, we do not have this phenomenon. I don't know who's told you that we have it."[83] The latter statement drew laughter from the audience.

[edit] ROTC ban

Since 1969, during the Vietnam War, the university has not allowed the US military to have Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) programs on campus.[84] However, even after 1969, Columbia students could participate in ROTC programs at other nearby colleges and universities.[85] [86][87] A few undergraduate Military Science courses were taught at Columbia as late as the 1970s.

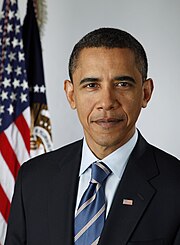

At a forum at the university during the 2008 presidential election campaign, both John McCain and Barack Obama said that the university should consider reinstating ROTC on campus. [87] [88] [89][90] After the debate, the President of the University, Lee Bollinger stated that he did not favor reinstating Columbia's ROTC program, because of the military's anti-gay policies. In November 2008, Columbia's undergraduate student body held a referendum on the question of whether or not to invite ROTC back to campus, and the students who voted were almost evenly divided on the issue. ROTC lost the vote (which would not have been binding on the administration) by a fraction of a percentage point.

[edit] Traditions

[edit] Orgo Night

On the day before the Organic Chemistry exam—which is often on the first day of finals—at precisely the stroke of midnight, the Columbia University Marching Band occupies Butler Library to distract diligent students from studying. After a half-hour of campus-interest jokes, the procession then moves out to the lawn in front of Hartley, Wallach and John Jay residence halls to entertain the residents there. The band then plays at various other locations around Morningside Heights, including the residential quadrangle of Barnard College, where students of the all-women's school, in mock-consternation, rain trash - including notes and course packets - and water balloons upon them from their dormitories above. The band tends to close their Orgo Night performances before Furnald Hall, known among students as the more studious and reportedly "anti-social" residence hall, where the underclassmen in the marching band serenade the seniors with an entertaining, though vulgar, mock-hymn to Columbia, composed of quips that poke fun at the various stereotypes about the Columbia student body.

[edit] Tree-Lighting and Yule Log ceremonies

The campus Tree-Lighting Ceremony is a relatively new tradition at Columbia, inaugurated in 1998. It celebrates the illumination of the medium-sized trees lining College Walk in front of Kent and Hamilton Halls on the east end and Dodge and Journalism Halls on the west, just before finals week in early December. The lights remain on until February 28. Students meet at the sun-dial for free hot chocolate, performances by various a cappella groups, and speeches by the university president and a guest.

Immediately following the College Walk festivities is one of Columbia's older holiday traditions, the lighting of the Yule Log. The ceremony dates to a period prior to the Revolutionary War, but lapsed before being revived by University President Nicholas Murray Butler in the early 20th century. A troop of students dressed as Continental Army soldiers carry the eponymous log from the sun-dial to the lounge of John Jay Hall, where it is lit amid the singing of seasonal carols.[91] The ceremony is accompanied by a reading of A Visit From St. Nicholas by Clement Clarke Moore (Columbia College class of 1798) and Yes, Virginia, There is a Santa Claus by Francis Pharcellus Church (Class of 1859).

[edit] The Varsity Show

An annual musical written by and for students and is one of Columbia's oldest traditions. Past writers and directors have included Columbians Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, Lorenz Hart, I.A.L. Diamond, and Herman Wouk. The show has one of the largest operating budgets of all university events.[92]

[edit] Faculty and research

Columbia was the first North American site where the Uranium atom was split. It was the birthplace of FM radio and the laser.[93] The MPEG-2 algorithm of transmitting high quality audio and video over limited bandwidth was developed by Dimitris Anastassiou, a Columbia professor of electrical engineering. Biologist Martin Chalfie was the first to introduce the use of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) in labelling cells in intact organisms.[94] Other inventions and products related to Columbia include Sequential Lateral Solidifcation (SLS) technology for making LCDs, System Management Arts (SMARTS), Session Initiation Protocol (SIP) (which is used for audio, video, chat, instant messaging and whiteboarding), pharmacopeia, Macromodel (software for computational chemistry), a new and better recipe for glass concrete, Blue LEDs, Beamprop (used in photonics), among others.[95]

Columbia scientists are credited with about about 175 new inventions in the health sciences each year.[95] More than 30 pharmaceutical products based on discoveries and inventions made at Columbia are on the market today. These include Remicade (for arthritis), Reopro (for blood clot complications), Xalatan (for glaucoma), Benefix, Latanoprost (a glaucoma treatment), shoulder prosthesis, homocysteine (testing for cardiovascular disease), and Zolinza (for cancer therapy).[96]

Columbia's Science and Technology Ventures currently manages some 600 patents and more than 250 active license agreements.[96] Patent-related deals earned Columbia more than $230 million in the 2006 fiscal year, according to the university.[97] In 2004, Columbia made $178 million (compared to $24 million made by Harvard).[97]

As of October 2008, 78 Columbia University affiliates have been honored with Nobel Prizes for their work in physics, chemistry, medicine, literature, peace, and economics.[98] In the last 12 years (1996-2008) 17 Columbia affiliates have won Nobel Prizes, of whom nine are current faculty members.

Columbia faculty awarded the Nobel Prize in the last 12 years (1996-2008) include Martin Chalfie (Chemistry, 2008), Orhan Pamuk (Literature, 2006), Edmund Phelps (Economics, 2006), Richard Axel (Physiology/Medicine, 2004), Joseph Stiglitz (Economics, 2001), Eric Kandel (Physiology/Medicine, 2000), Robert Mundell (Economics, 1999), Horst Ludwig Störmer (Physics, 1998), and William Vickrey (Economics, 1996). Columbia affiliates awarded the Nobel Prize in the last 12 years (1996-2008) include Al Gore (Peace, 2007), John Mather (Physics, 2006), Robert Grubbs (Chemistry, 2005), Linda Buck (Physiology/Medicine, 2004), William Standish Knowles (Chemistry, 2001), James Heckman (Economics, 2000), Louis Ignarro (Physiology/Medicine, 1998), and Robert Merton (Economics, 1997).

Other awards and honors won by current faculty include 28 MacArthur Foundation Award winners,[99] 4 National Medal of Science recipients,[99] 41 National Academy of Sciences Award winners,[99] 20 National Academy of Engineering Award winners,[100] 38 Institute of Medicine of the National Academies Award recipeints[101] and 143 American Academy of Arts and Sciences Award winners.[99]

[edit] Notable Columbians

[edit] Alumni and famous past students

The current President of the United States of America, Barack Obama, as well as two former Presidents of the United States, the Roosevelts, attended Columbia. Obama graduated in 1983. Neither of the Roosevelts earned a degree; it was common at the time for young men to enter the bar after completing only a year or two of legal education.[102] Nine Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States have studied at the University and 39 Nobel Prize winners have obtained degrees from Columbia. Alumni also have received more than 20 National Book Awards and more than 90 Pulitzer Prizes. Four United States Poet Laureates have received their degrees from Columbia. Today, three United States Senators and 16 current Chief Executives of Fortune 500 companies hold Columbia degrees, as do seven of the 25 richest Americans[103]. Alumni of the University have served (in more than 70 positions) as members of U.S. Presidential Cabinets or as U.S. Presidential advisers. More than 40 U.S. senators, 90 U.S. congresspersons, and 35 U.S. governors have received their education at Columbia. Alumni have founded or been the president of more than fifty-five universities and colleges in the nation and the world.

Attendees of King's College, Columbia's predecessor, included Founding Fathers Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Robert R. Livingston, and Gouverneur Morris.

U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justices Harlan Fiske Stone, Charles Evans Hughes and Associate Justices Benjamin Cardozo and William O. Douglas were graduates of the law school. Former U.S. Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin Delano Roosevelt attended the law school but did not graduate.[104]

Former U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower served as President of the University. Other significant figures in American history to attend the university were John L. O'Sullivan, the journalist who coined the phrase "manifest destiny," Alfred Thayer Mahan, the geostrategist who wrote on the significance of sea power, Jewish philanthropist Sampson Simson and progressive intellectual Randolph Bourne. Former Secretary of State Alexander Haig studied at Columbia Business School between 1954 and 1955. Wellington Koo, a Chinese diplomat who argued passionately against Japanese and Western imperialism in Asia at the Paris Peace Conference, is a

graduate, having honed his debating skills in Columbia's Philolexian Society, as is Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar, one of the founding fathers of India and chief architect of its constitution. Local politicians have been no less represented at Columbia, including Seth Low, who served as both President of the University and Mayor of the City of New York, and New York governors Thomas Dewey, also an unsuccessful US presidential candidate, DeWitt Clinton, who presided over the construction of the Erie Canal, Hamilton Fish, later to become US Secretary of State, and Daniel D. Tompkins, who also served as a Vice President of the United States.

Toomas Hendrik Ilves, the President of Estonia, received his BA in psychology at Columbia in 1976. Abdul Zahir (Afghan Prime Minister) received his MD from Columbia University. Philip Gunawardena, a Sri Lankan Revolutionary and Indian Freedom Fighter, who was later to be known as "The Father of Socialism in Sri Lanka", joined Columbia in 1925 for his post-graduate studies. He was later to become a Cabinet Minister, instituting far-reaching changes in Sri Lanka's agrarian structure. General, historian, and author John Watts de Peyster, who was influential in the modernization of the New York National Guard, New York Police Department, and the Fire Department of New York, attended Columbia College and later received a M.A. degree.

More recent political figures educated at Columbia include U.S. President Barack Obama, current U.S. Senators Mike Gravel of Alaska, Judd Gregg of New Hampshire and Frank Lautenberg of New Jersey, Governor of New York David Paterson and his Chief of Staff Charles J. O'Byrne, US Attorney General Eric Holder, former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, UN weapons inspector Hans Blix, former UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali, conservative commentators Patrick J. Buchanan and Norman Podhoretz, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, former chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank Alan Greenspan, George Stephanopoulos, Senior Advisor to former U.S. President Bill Clinton, George Pataki, the former governor of New York State, and Mikhail Saakashvili, the current President of the country of Georgia. Louisiana Lieutenant Governor (1956–1960) Lether Frazar, who was president of two universities in his state, obtained his Ph.D. from Columbia in 1942. Warlick Carr, a prominent attorney in Lubbock attended Columbia for a year before transferring to the University of Texas at Austin.

Scientists Stephen Jay Gould, Robert Millikan and Michael Pupin, cultural historian Jacques Barzun, literary critic Lionel Trilling, sociologists Immanuel Wallerstein and Seymour Martin Lipset, porn actress Sasha Gray[citation needed], behavioral psychologist Charles Ferster, poet-professor Mark Van Doren, philosophers Irwin Edman and Robert Nozick, and economists Milton Friedman, Former Afghan Finance Minister Ashraf Ghani, Nur Mohammed Taraki (Prime Minister and President of Afghanistan, 1978–1979), Daniel C. Kurtzer, and communications economist Harvey J. Levin all obtained degrees from Columbia.

In culture and the arts, Rodgers and Hammerstein, Lorenz Hart, screenwriters Sidney Buchman and I.A.L. Diamond, critic and biographer Tim Page, musician Art Garfunkel, and children's songwriter Bobby Susser, are all among Columbia's alumni. The poets Langston Hughes, Federico García Lorca, Joyce Kilmer and John Berryman; the writers Eudora Welty, Isaac Asimov, J. D. Salinger, Upton Sinclair, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Phyllis Haislip, Roger Zelazny, Herman Wouk, Hunter S. Thompson, Aravind Adiga and Paul Auster; playwrights Tony Kushner and Eulalie Spence; the architects Robert A. M. Stern, Ricardo Scofidio, Peter Eisenman and Christine Wang; the composer Béla Bartók; and film director and screenwriter Cetywa Powell also attended the university. Trappist monk, author, and humanist Thomas Merton is an alumnus both as an undergraduate and graduate student, and converted to Catholicism while attending. Silent Film actress Miriam Cooper attended writing courses at the school during her later years. Urban theorist and cultural critic Jane Jacobs spent time at the School of General Studies, and educator Elisabeth Irwin received her M.A. there in 1923. Vampire Weekend band members Ezra Koenig, Rostam Batmanglij, Chris Tomson, and Chris Baio graduated from the College in 2006 and 2007. Grammy Award-winning R&B singers Lauryn Hill and Alicia Keys attended Columbia, but both left after one year. Singer and songwriter Sean Lennon, son of John Lennon and Yoko Ono, as well as Japanese-American pop-star Hikaru Utada and Korean-American pop-star Lena Park briefly attended the College before leaving to pursue their singing careers. Allison Starling and Remy Zaken, both Broadway actresses, are currently attending the College. Young adult author Maureen Johnson graduated from Columbia with an M.F.A. in writing and theatrical dramaturgy.

Baseball legends Lou Gehrig, Mo Berg (of the biography The Catcher Was a Spy) and Sandy Koufax, along with football quarterback Sid Luckman and sportscaster Roone Arledge, are alumni.

Celebrities who graduated from Columbia include the actors Maggie Gyllenhaal, Casey Affleck, Julia Stiles, Amanda Peet, Matthew Fox, Famke Janssen, Brian Dennehy, Jesse Bradford, Ben Stein, George Segal, Rider Strong and Mario Van Peebles. Academy Award-winning actors James Cagney and Anna Paquin, and Academy Award-nominated actors Ed Harris and Jake Gyllenhaal attended Columbia for a time before leaving to pursue their acting careers. Radio personality Tom Griswold of the nationally syndicated morning radio show The Bob and Tom Show graduated from Columbia. Television talk show host Sally Jesse Raphael is a graduate and Claire-Aimee "Claire" Unabia from Cycle 10 of America's Next Top Model is a graduate of the School of General Studies. [105]

Amelia Earhart also enrolled at Columbia as a pre-med student in 1919.

[edit] Faculty and affiliates

Jacques Barzun, Lionel Trilling, and Mark Van Doren were legendary Columbia faculty members as well as graduates, teaching alongside such luminaries as the philosopher John Dewey, American historians Richard Hofstadter, John A. Garraty, Charles Beard and Reinhard H Luthin, educator George Counts, sociologists Daniel Bell, C. Wright Mills, Robert K. Merton, and Paul Lazarsfeld, and art historian Meyer Schapiro. The history of the discipline of anthropology practically begins at Columbia with Franz Boas. Margaret Mead, a Barnard College alumna, along with Columbia graduate Ruth Benedict, continued this tradition by bringing the discipline into the spotlight. Nuclear physicists Enrico Fermi, John R. Dunning, I. I. Rabi, and Polykarp Kusch helped develop the Manhattan Project at the university, and pioneering geophysicist Maurice Ewing made great strides in the understanding of plate tectonics. Thomas Hunt Morgan discovered the chromosomal basis for genetic inheritance at his famous "fly room" at the university, laying the foundation for modern genetics. Philosopher Hannah Arendt was a visiting professor in the 1960s. Noted Chinese author and illustrator, Chiang Yee taught Chinese from 1955 to 1977, and retired as Emeritus Professor of Chinese. In 1978 Frank Daniel began his Columbia teaching career; he is most notable for his development of the sequence paradigm of screenwriting.

Melvil Dewey, creator of the Dewey Decimal Classification, was librarian of the University and also founded the first library school in the U.S. at Columbia. More recently, architects Bernard Tschumi, Santiago Calatrava and Frank Gehry have taught at the school. The postcolonial scholar Edward Said taught at Columbia, where he spent virtually the entirety of his academic career, until his death in 2003.

Current faculty (2008-2009 Academic Year) includes 9 Nobel Laureates: R. Axel, M. Chalfie, E. Kandel, T.D. Lee, R. Mundell, O. Pamuk, E. Phelps, J. Stiglitz, and H. Stormer.

Also, celebrated faculty members include string-theory expert Brian Greene, Ricci flow inventor Richard Hamilton, American historian Eric Foner, Middle Eastern studies expert Richard Bulliet, Eric Kandel, a Nobel prize winner who conducted fundamental research in neuroscience, New York City historian Kenneth T. Jackson, Je Tsong Khapa Professor of Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Studies Robert Thurman, composers Tristan Murail, Fred Lerdahl and George Lewis, literary theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, philosopher Philip Kitcher, British historian Simon Schama, art historian Rosalind Krauss, director Mira Nair, East Asian studies expert William Theodore de Bary, scientist, critic, writer and physician Oliver Sacks, This American Life producer Alex Blumberg, Turkish author and Nobel prize winner Orhan Pamuk, and economists Jeffrey Sachs, Jagdish Bhagwati, Joseph Stiglitz, Edmund Phelps, Xavier Sala-i-Martin, and Robert Mundell.

Sunil Gulati, President of US Soccer, is a professor of Economics at the University. Dr. Michael Stone is a Professor of Psychiatry. He is the star of the I.D. show Most Evil, and a foreleading expert in forensic psychiatry.

[edit] Fictitious Columbians

For more information on this topic, see Columbia University in Films and Television.

[edit] Film and television

| Lists of miscellaneous information should be avoided. Please relocate any relevant information into appropriate sections or articles. (January 2009) |

Movies featuring scenes shot on the Morningside campus include:

[edit] In geography

The Columbia Glacier, one of the largest in Alaska's College Fjord, is named after the university, where it sits among other glaciers named for the Ivy League and Seven Sisters schools. Mount Columbia in the Collegiate Peaks Wilderness of Colorado also takes its name from the university and is situated among peaks named for Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Oxford.

[edit] See also

- 116th Street–Columbia University (IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line) a station in the New York City subway system

- Columbia/Barnard Hillel, a Jewish student organization at Columbia University

- Columbia Blue, a standardized color combination in the Pantone Matching System, used as a school color by Columbia University

- Columbia Center for New Media Teaching and Learning

- Columbia-Chicago School of Economics

- Columbia College of Columbia University, the main undergraduate college at Columbia University, New York

- Columbia Daily Spectator, a student newspaper at Columbia University, New York

- Columbia Glacier, a glacier in Alaska, USA, named for Columbia University

- Columbia Grammar & Preparatory School, New York City

- Columbia Institute for Tele-Information, New York City

- Columbia Journalism Review, a bimonthly journal published by the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism

- Columbia Law School

-

- Columbia Business Law Review, a monthly journal published by students at Columbia Law School

- Columbia Human Rights Law Review, a law review published by students at Columbia Law School

- Columbia Law Review, a monthly law review published by students at Columbia Law School

- Columbia Lions of Columbia University

- Columbia MM, a text-based mail client developed at Columbia University

- Columbia Non-neutral Torus, a small stellarator at the Columbia University Plasma Physics Laboratory

- Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center (album), an album of electronic music released in 1961

- Columbia Political Review, a journal published by the Columbia Political Union at Columbia University

- Columbia Queer Alliance at Columbia University, the oldest such student organization in the United States

- Columbia Scholastic Press Association

- Columbia Soccer Stadium at Columbia University

- Columbia Spelling Board a historic etymological organization

- Columbia Revolt, a black-and-white 1968 documentary film

- Columbia Undergraduate Science Journal published by students at Columbia University

- Columbia University Marching Band

- Columbia University Tunnels

- Columbia University Library System

- Columbia University Medical Center, New York

- Columbia University Press, publisher of the Columbia Encyclopedia

- Education in New York City

- Go Ask Alice!

- Goddard Institute for Space Studies

- Jester of Columbia

- John Bates Clark Medal

- List of Columbia University people

- Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize

- Medical School for International Health

- Nobel laureates by university affiliation

- Teachers College, Columbia University's Graduate School of Education

- The Bancroft Prize

- Biosphere2

- The Blue and White

- The Earth Institute

- The Fed

- The Philolexian Society

- The Pulitzer Prize

- The School at Columbia University, New York City

- The Varsity Show

- WKCR

[edit] References

- ^ Columbia Finance Division Clarifies Erroneous Endowment Report | Endowment

- ^ http://www.columbia.edu/cu/opir/abstract/full_time_faculty_gender2007.htm

- ^ a b c http://www.columbia.edu/cu/opir/abstract/enrollment_fte_level_2004-2007.htm

- ^ Columbia University Office of Undergraduate Admissions - Housing & Dining

- ^ Tan, Tao (2004). "The Evolution of Morningside". http://www.columbia.edu/~tt2124/CUHist/. Retrieved on 2006-08-10.

- ^ Sources vary; e.g. "FACTS 2005: Libraries". Planning and Institutional Research. Columbia University Office of the Provost. 14 September 2005. http://www.columbia.edu/cu/opir/facts.html?libraries. Retrieved on 2006-08-10.: "9.5 million printed volumes"; "The Nation's Largest Libraries: A Listing By Volumes Held, ALA Library Fact Sheet Number 22". American Library Association. December , 2006. http://www.ala.org/Template.cfm?Section=libraryfactsheet&Template=/ContentManagement/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=101295. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.: 9,277,042 "volumes held."

- ^ According to the Royal Institute of British Architects (R.I.B.A.)

- ^ Columbia’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library Acquires Early Thirteenth-Century Manuscript Bible

- ^ Columbia University Libraries [1]

- ^ Pulimood, Steven K. (May 7, 2002). "116th was Gnomon's Land". Columbia Spectator. http://www.columbiaspectator.com/media/storage/paper865/news/2002/05/07/ArtsEntertainment/116th.Was.Gnomons.Land-2038876.shtml?norewrite200608101408&sourcedomain=www.columbiaspectator.com. Retrieved on 2006-08-10.

- ^ McCaughey, Robert A. (September 15, 2004). "Farewell, Aristocracy - The World Turned Upside Down". Social History of Columbia University Fall 2004 Lectures. http://beatl.barnard.columbia.edu/cuhis3057/04Lectures/04Lecture3.htm. Retrieved on 2006-08-10.

- ^ Schecter, Barnet. The Battle for New York: The City at the Heart of the American Revolution. Walker & Company. New York. October 2002. ISBN 0-8027-1374-2

- ^ McCullough, David. 1776. Simon & Schuster. New York. May 24, 2005. ISBN 978-0743226714

- ^ Chernow, Ron. Alexander Hamilton. Penguin Books, (2004) (ISBN 1-59420-009-2)

- ^ a b c d A History of Columbia University, 1754-1904. New York: Macmillan. 1904. ISBN 1402137370.

- ^ a b McCaughey, Robert (December 10, 2003). "Appendix E: Institutional Comparisons". Stand, Columbia - A History of Columbia University. Columbia University Press. http://beatl.barnard.columbia.edu/stand_columbia/e.html. Retrieved on 2006-08-10.

- ^ McCaughey, Robert (December 10, 2003). "Leading American University Producers of PhDs, 1861–1900". Stand, Columbia - A History of Columbia University. Columbia University Press. http://beatl.barnard.columbia.edu/stand_columbia/phdleaders1861-1900.html. Retrieved on 2006-08-10.

- ^ Columbia College Student Life Timeline

- ^ "Low Memorial Library". 2002-07-30. http://www.gs.columbia.edu/kevinmap/lowmemorial.htm. Retrieved on 2006-08-10.

- ^ "Why They Called It the Manhattan Project". http://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/30/science/30manh.html. Retrieved on 2007-10-30.

- ^ "Manhattanville in West Harlem". http://neighbors.columbia.edu/pages/manplanning/index.html. Retrieved on 2007-04-01.

- ^ Williams, Timothy (November 20, 2006). "In West Harlem Land Dispute, It's Columbia vs. Residents". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/20/nyregion/20columbia.html?em&ex=1164171600&en=85fc31aebe9f875c&ei=5087%.