Equation of time

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The equation of time is the difference over the course of a year between time as read from a sundial and time as read from a clock, measured in an ideal situation (ie. in a location at the centre of a time zone, and which does not use daylight saving time). The sundial can be ahead (fast) by as much as 16 min 33 s (around November 3) or fall behind by as much as 14 min 6 s (around February 12). It is caused by irregularity in the path of the Sun across the sky, due to a combination of the obliquity of the Earth's rotation axis and the eccentricity of its orbit. The equation of time is the east or west component of the analemma, a curve representing the angular offset of the Sun from its mean position on the celestial sphere as viewed from Earth.

The equation of time was used historically to set clocks. Between the invention of accurate clocks in 1656 and the advent of commercial time distribution services around 1900, the common way to set clocks was by observing the passage of the sun across the local meridian at noon. The moment the sun passed overhead, the clock was set to noon, offset by the number of minutes given by the equation of time for that date.[1] The equation of time values for each day of the year, compiled by astronomical observatories, were widely listed in almanacs and ephemerides.[2][3]

Naturally, other planets will have an equation of time too. On Mars the difference between sundial time and clock time can be as much as 50 minutes, due to the considerably greater eccentricity of its orbit.

Contents |

[edit] Apparent time versus mean time

The irregular daily movement of the Sun was known by the Babylonians, and Ptolemy has a whole chapter in the Almagest devoted to its calculation (Book III, chapter 9). However he did not consider the effect relevant for most calculations as the correction was negligible for the slow-moving luminaries. He only applied it for the fastest-moving luminary, the moon.

Until the invention of the pendulum and the development of reliable clocks towards the end of the 17th century, the equation of time as defined by Ptolemy remained a curiosity, of importance only to astronomers. However, when mechanical clocks started to take over timekeeping from sundials, which had served humanity for centuries, the difference between clock time and solar time became an issue. Apparent solar time (or true or real solar time) is the time indicated by the Sun on a sundial, while mean solar time is the average as indicated by clocks. The first accurate tables for the equation of time were published in 1665 by Christiaan Huygens.[4] Following the practice of earlier astronomers Huygens increased his values for the equaton of time by a constant to make all values positive throughout the year. Another set of tables published in 1672 by John Flamsteed, the first head of the new Greenwich Observatory, was the first to adopt the modern convention using positive and negative values for the equation of time.[5]

Until 1833, the equation of time was mean minus apparent solar time in the British Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris. Earlier, all times in the almanac were in apparent solar time because time aboard ship was determined by observing the Sun. In the unusual case that the mean solar time of an observation was needed, the extra step of adding the equation of time to apparent solar time was needed. Since 1834, all times have been in mean solar time because by then the time aboard most ships was determined by marine chronometers. In the unusual case that the apparent solar time of an observation was needed, the extra step of adding the equation of time to mean solar time was needed, requiring all differences in the equation of time to have the opposite sign.

As the daily movement of the Sun is one revolution per day, that is 360° every 24 hours, and the Sun itself appears as a disc of about 0.5° in the sky, simple sundials can be read to a maximum accuracy of about one minute. Since the equation of time has a range of about 30 minutes, the difference between sundial time and clock time cannot be ignored. In addition to the equation of time, one also has to apply corrections due to one's distance from the local time zone meridian and summer time, if any.

The tiny increase of the mean solar day itself due to the slowing down of the Earth's rotation, by about 2 ms per day per century, which currently accumulates up to about 1 second every year, is not taken into account in traditional definitions of the equation of time, as it is statistically insignificant at the accuracy level of sundials.

[edit] Eccentricity of the Earth's orbit

The Earth revolves around the Sun. As such it appears that the Sun makes one rotation around the Earth in one year. If the Earth orbited the Sun with a constant speed, in a circular orbit in a plane perpendicular to the Earth's axis, then the Sun would culminate every day at exactly the same time, and be a perfect time keeper (except for the very small effect of its slowing rotation). But the orbit of the Earth is an ellipse, and its speed varies between 30.287 and 29.291 km/s, according to Kepler's laws of planetary motion, and its angular speed also varies, and thus the Sun appears to move faster at perihelion (currently around 3 January) and slower at aphelion a half year later. At these extreme points, this effect increases (respectively, decreases) the real solar day by 7.9 seconds from its mean. This daily difference accumulates over a period. As a result, the eccentricity of the Earth's orbit contributes a sine wave variation with an amplitude of 7.66 minutes and a period of one year to the equation of time. The zero points are reached at perihelion (at the beginning of January) and aphelion (beginning of July) while the maximum values are in early April (negative) and early October (positive).

[edit] Obliquity of the ecliptic

However, even if the Earth's orbit were circular, the motion of the Sun along the celestial equator would still not be uniform. This is a consequence of the tilt of the Earth's rotation with respect to its orbit, or equivalently, the tilt of the ecliptic (the path of the sun against the celestial sphere) with respect to the celestial equator. The projection of this motion onto the celestial equator, along which "clock time" is measured, is a maximum at the solstices, when the yearly movement of the Sun is parallel to the equator and appears as a change in right ascension, and is a minimum at the equinoxes, when the Sun moves in a sloping direction and appears mainly as a change in declination, leaving less for the component in right ascension, which is the only component that affects the duration of the solar day. As a consequence of that, the daily shift of the shadow cast by the Sun in a sundial, due to obliquity, is smaller close to the equinoxes and greater close to the solstices. At the equinoxes, the Sun is seen slowing down by up to 20.3 seconds every day and at the solstices speeding up by the same amount.

In the figure on the right, we can see the monthly variation of the apparent slope of the plane of the ecliptic at solar midday as seen from Earth. This variation is due to the apparent precession of the rotating Earth through the year, as seen from the Sun at solar midday.

In terms of the equation of time, the inclination of the ecliptic results in the contribution of another sine wave variation with an amplitude of 9.87 minutes and a period of a half year to the equation of time. The zero points of this sine wave are reached at the equinoxes and solstices, while the maxima are at the beginning of February and August (negative) and the beginning of May and November (positive).

[edit] Secular effects

The two above mentioned factors have different wavelengths, amplitudes and phases, so their combined contribution is an irregular wave. At epoch 2000 these are the values (in minutes and seconds):

| minimum | −14:15 | 11 February |

| zero | 00:00 | 15 April |

| maximum | +03:41 | 14 May |

| zero | 00:00 | 13 June |

| minimum | −06:30 | 26 July |

| zero | 00:00 | 1 September |

| maximum | +16:25 | 3 November |

| zero | 00:00 | 25 December |

E.T. = apparent − mean. Positive means: Sun runs fast and culminates earlier, or the sundial is ahead of mean time. A slight yearly variation occurs due to presence of leap years, resetting itself every 4 years.

The exact shape of the equation of time curve and the associated analemma slowly changes over the centuries due to secular variations in both eccentricity and obliquity. At this moment both are slowly decreasing, but they increase and decrease over a timescale of hundreds of thousands of years. When the eccentricity, now 0.0167, reaches 0.047, the eccentricity effect may in some circumstances overshadow the obliquity effect, leaving the equation of time curve with only one maximum and minimum per year, as is the case on Mars[1].

On shorter timescales (thousands of years) the shifts in the dates of equinox and perihelion will be more important. The former is caused by precession, and shifts the equinox backwards compared to the stars. But it can be ignored in the current discussion as our Gregorian calendar is constructed in such a way as to keep the vernal equinox date at 21 March (at least at sufficient accuracy for our aim here). The shift of the perihelion is forwards, about 1.7 days every century. For example in 1246 the perihelion occurred on 22 December, the day of the solstice. At that time the two contributing waves had common zero points, and the resulting equation of time curve was symmetrical. Before that time the February minimum was larger than the November maximum, and the May maximum larger than the July minimum. The secular change is evident when one compares a current graph of the equation of time (see below) with one from about 2000 years ago, for example, one constructed from the data of Ptolemy.

[edit] Practical use

If the gnomon (the shadow-casting object) is not an edge but a point (e.g., a hole in a plate), the shadow (or spot of light) will trace out a curve during the course of a day. If the shadow is cast on a plane surface, this curve will (usually) be the conic section of the hyperbola, since the circle of the Sun's motion together with the gnomon point define a cone. At the spring and fall equinoxes, the cone degenerates into a plane and the hyperbola into a line. With a different hyperbola for each day, hour marks can be put on each hyperbola which include any necessary corrections. Unfortunately, each hyperbola corresponds to two different days, one in each half of the year, and these two days will require different corrections. A convenient compromise is to draw the line for the "mean time" and add a curve showing the exact position of the shadow points at noon during the course of the year. This curve will take the form of a figure eight and is known as an "analemma". By comparing the analemma to the mean noon line, the amount of correction to be applied generally on that day can be determined.

[edit] More details

In general, the equation of time is equal to

where α is the Sun's right ascension, M is the mean anomaly, and ψ is the angle from the periapsis to the vernal equinox. Using spherical trigonometry, the right ascension is given by

where  is the true anomaly and

is the true anomaly and  is the Sun's declination. The declination in turn is given by

is the Sun's declination. The declination in turn is given by

where  is the obliquity.

is the obliquity.

In practice, it may be easier and faster to use an approximation for the curve rather than the exact formula. For Earth, the equation of time resembles the sum of two offset sine curves, with periods of one year and six months respectively. It can be approximated using this formula:

where E is in minutes and

if sin and cos have arguments in degrees,

or

if sin and cos have arguments in radians.

Here, N is the so-called day number; i.e.,

- N = 1 for January 1,

- N = 2 for January 2,

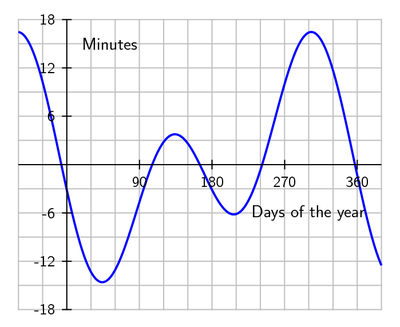

The following is a graph of the current equation of time.

Notice that the appearance of this graph can be directly deduced from the time evolution of the projection into the celestial equator of the Earth's Analemma loop trajectory.

From one year to the next, the equation of time can vary by as much as 20 seconds, mainly due to leap years. [2].

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- Meeus, Jean (1997). Mathematical Astronomy Morsels. Richmond: Willmann-Bell. pp. 337–346. ISBN 0-943396-51-4.

[edit] External links

- Graphical Visualisation of Equation of Time - Constantly updated

- Table giving the Equation of Time and the declination of the sun for every day of the year

- The equation of time described on the Royal Greenwich Observatory website

- An analemma site with many illustrations

- The Equation of Time and the Analemma, by Kieron Taylor

- An article by Brian Tung containing a link to a C program using a more accurate formula than most (particularly at high inclinations and eccentricities). The program can calculate solar declination, Equation of Time, or Analemma.

- Doing calculations using Ptolemy's geocentric planetary models with a discussion of his E.T. graph

- The equation of time correction-table A page describing how to correct a clock to a sundial.

- An example of an Audemars Piguet mechanical wristwatch containing this concept as a complication, including a description of the implementation in horology and several videos/animations.

- Two more examples of a mechanical wristwatch containing this complication, manufactured by Blancpain: Part 1 Part 2.

- Equation of Time Longcase Clock by John Topping C.1720

- Solar tempometer - Calculate your solar time including the equation of time.

[edit] Footnotes

- ^ Olmstead, Dennison (1866). A Compendium of Astronomy. New York: Collins & Brother. http://books.google.com/books?id=QUwAAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA57. pp. 57–58

- ^ Milham, Willis I. (1945). Time and Timekeepers. New York: MacMillan. ISBN 0780800087. pp. 11–15

- ^ See for example, British Commission on Longitude (1794). Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris for the year 1803. London, UK: C. Bucton. http://books.google.com/books?id=CPgNAAAAQAAJ&pg=PT2. p.14

- ^ Huygens, Christiaan (1665). Kort Onderwys aengaende het gebruyck der Horologien tot het vinden der Lenghten van Oost en West. The Hague: [publisher unknown]. http://www.xs4all.nl/~adcs/Huygens/17/kort.html.

- ^ Flamsteed, John (1672). De Inaequalitate Dierum Solarium. London: William Godbid.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||