Scots language

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Scots | ||

|---|---|---|

| Spoken in: | Northern Isles, Caithness, Scottish Lowlands, Ulster, England adjacent to the border with Scotland. | |

| Total speakers: | est. 200,000 (ethnologue) to over 1.5 million (General Register Office for Scotland, 1996) | |

| Language family: | Indo-European Germanic West Germanic Anglo-Frisian Scots |

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in: | None. — Classified as a "traditional language" by the Scottish Government. — Classified as a "regional or minority language" under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, ratified by the United Kingdom in 2001. — Classified as a "traditional language" by The North/South Language Body. |

|

| Regulated by: | — Scotland: None, although the Dictionary of the Scots Language carries great authority (the Scottish Government's Partnership for a Better Scotland coalition agreement (2003) promises "support"). — Ireland: None, although the cross-border Ulster-Scots Agency, established by the Implementation Agreement following the Good Friday Agreement promotes usage. |

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1: | None | |

| ISO 639-2: | sco | |

| ISO 639-3: | sco | |

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Scots or Lowland Scots refers to the Germanic varieties derived from Middle English spoken in parts of Lowland Scotland, Northern Ireland and the border areas of the Republic of Ireland. It is not to be confused with Scottish Gaelic, the surviving Celtic language of Scotland. Native speakers in Scotland and Ireland usually[citation needed] refer to their vernacular as "braid Scots" (broad Scots in English) or use a dialect name such as "Teri", "the Doric" or "the Buchan Claik". The old-fashioned "Scotch" occurs occasionally, especially in Ireland. The term Lallans ("of the Lowlands") is used too, though this is more often taken to mean the specific Lallans literary form. Scots in Ireland is known in official circles as "Ulster Scots" or Ullans.

Since there are no universally accepted criteria for distinguishing languages from dialects, scholars and other interested parties often disagree about the linguistic, historical and social status of Scots. Although a number of paradigms for distinguishing between languages and dialects do exist, these often render contradictory results. Consequently, Scots is sometimes treated as a variety of English, but with its own distinct dialects. Although the exact difference between Scots and Standard Scottish English is unclear, Scots is often treated by others as a distinct Germanic language, in the way Norwegian is distinct from Danish, with Scottish English being thought of as the English dialect of Scotland.

Contents |

[edit] History

The word Scot was borrowed from Latin to refer to Scotland and dates from at least the first half of the 10th century. Up to the 15th century Scottis (modern form: Scots) referred to Gaelic (a Celtic language and tongue of the ancient Scots, introduced from Ireland perhaps from the 4th century onwards). Since the late 15th century,[1] Germanic speakers in Scotland also started occasionally referring to their vernacular as Scottis and increasingly called Gaelic Erse (from Erisch, or "Irish"), now often considered pejorative.

Northumbrian Old English had been established in southeastern Scotland as far as the River Forth by the 7th century. It remained largely confined to this area until the 13th century, continuing in common use while Gaelic was the court language. Early northern Middle English, also known as Early Scots, then spread further into Scotland via the burghs, proto-urban institutions which were first established by King David I. The growth in prestige of Early Scots in the 14th century, and the complementary decline of French in Scotland, made Scots the prestige language of most of eastern Scotland. By the 16th century Middle Scots had established orthographic and literary norms largely independent of those developing in England.

Modern Scots thus grew out of the early northern form of Middle English spoken by the people of southeastern Scotland and northern England. Northern Middle English, or Early Scots as it is also known, made its first literary appearance in Scotland in the mid-14th century, when its form differed little from northern English dialects, and so Scots shared many Northumbrian borrowings from Old Norse and Anglo-Norman French. Later influences include Dutch and Middle Low German through trade with and immigration from the low countries, as well as Romance via ecclesiastical and legal Latin and French owing to the Auld Alliance. Scots has loan words resulting from contact with Gaelic. Early medieval legal documents show a language peppered with Gaelic legal and administrative loans. Today Gaelic loans are mainly for geographical and cultural features, such as ceilidh, loch and clan.

[edit] Status

Before the Treaty of Union 1707, when Scotland and England joined to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, there is ample evidence that Scots was widely held to be an independent language[2] as part of a pluricentric diasystem.

The linguist Heinz Kloss considered Modern Scots a Halbsprache (half language) in terms of a Ausbausprache - Abstandsprache - Dachsprache framework although today, in Scotland, most people's speech is somewhere on a continuum ranging from traditional broad Scots to Scottish Standard English. Many speakers are either diglossic and/or able to code-switch along the continuum depending on the situation in which they find themselves. Where on this continuum English-influenced Scots becomes Scots-influenced English is difficult to determine. Since standard English now generally has the role of a Dachsprache, disputes often arise as to whether or not the varieties of Scots are dialects of Scottish English or constitute a separate language in their own right.

The UK government now accepts Scots as a regional language and has recognised it as such under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.

Notwithstanding the UK government’s and the Scottish Executive’s obligations under part II of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, the Scottish Executive recognises and respects Scots (in all its forms) as a distinct language, and does not consider the use of Scots to be an indication of poor competence in English.

—[3]

Evidence for its existence as a separate language lies in the extensive body of Scots literature, its independent — if somewhat fluid — orthographic conventions and in its former use as the language of the original Parliament of Scotland.[4] Since Scotland retained distinct political, legal and religious systems after the Union, many Scots terms passed into Scottish English. For instance, libel and slander, separate in English law, are bundled together as defamation in Scots law.

After the Union and the shift of political power to England, the use of Scots was discouraged by many in authority and education, as was the notion of Scottishness itself.[5] Many leading Scots of the period, such as David Hume, considered themselves Northern British rather than Scottish.[6] They attempted to rid themselves of their Scots in a bid to establish standard English as the official language of the newly formed Union. Enthusiasm for this new Britishness waned over time, and the use of Scots as a literary language was revived by several prominent Scotsmen such as Robert Burns. Such 18th and 19th century writers were well aware of cross-dialect standard literary norms, but during the first half of the 20th century, knowledge of such norms waned and currently there is no institutionalised standard literary form.[7] During the second half of the 20th century, enthusiasts developed regularised cross-dialect forms following historical orthographic conventions, but these have had a limited impact. In much contemporary written Scots language, local loyalties usually prevail, and the written form usually adopts standard English sound-to-letter correspondences to represent the local pronunciation.

No education takes place through the medium of Scots, though English lessons may cover it superficially, which usually entails reading some Scots literature and observing local dialect. Much of the material used is often Standard English disguised as Scots, which has upset both proponents of Standard English and proponents of Scots alike.[8] One example of the educational establishment's approach to Scots is "Write a poem in Scots. (It is important not to be worried about spelling in this – write as you hear the sounds in your head.)",[9] whereas guidelines for English require teaching pupils to be "writing fluently and legibly with accurate spelling and punctuation."[10] Scots can also be studied at university level.

The use of Scots in the media is scant and is usually reserved for niches where local dialect is deemed acceptable, e.g., comedy, Burns Night, or representations of traditions and times gone by. Serious use for news, encyclopaedias, documentaries, etc. rarely occurs in Scots, although the Scottish Parliament website offers some information on it.

It is often held that, had Scotland remained independent, Scots would have remained and been regarded as a separate language from English.[citation needed] On the other hand, a situation similar to that of Swiss German and standard German might have occurred. Equally, the present situation might have occurred, where the social elites and the upwardly mobile adopted Standard English, causing institutional language shift. A model of language revival to which many enthusiasts aspire is that of the Catalan language in areas spanning parts of Spain, France, Andorra and Italy, particularly as regards the situation of Catalan in Catalonia.

[edit] Number of speakers

It has been difficult to determine the number of speakers of Scots via census, because many respondents might interpret the question "Do you speak Scots?" in different ways. Campaigners for Scots pressed for this question to be included in the 2001 U.K. National Census. The results from a 1996 trial before the Census, by the General Register Office for Scotland[citation needed], suggested that there were around 1.5 million speakers of Scots, with 30% of Scots responding "Yes" to the question "Can you speak the Scots language?", but only 17% responding "Yes." to the question "Can you speak Scots?". (It was also found that older, working-class people were more likely to answer in the affirmative.) The University of Aberdeen Scots Leid Quorum performed its own research in 1995, suggesting that there were 2.7 million speakers.[citation needed] The GRO questions, as freely acknowledged by those who set them, were not as detailed and as systematic as the Aberdeen University ones, and only included reared speakers, not those who had learned the language. Part of the difference resulted from the central question posed by surveys: "Do you speak Scots?". In the Aberdeen University study, the question was augmented with the further clause "… or a dialect of Scots such as Border &c.?", which resulted in greater recognition from respondents. The GRO concluded that there simply wasn't enough linguistic self-awareness amongst the Scottish populace, with people still thinking of themselves as speaking badly pronounced, grammatically inferior English rather than Scots, for an accurate census to be taken. The GRO research concluded that "[a] more precise estimate of genuine Scots language ability would require a more in-depth interview survey and may involve asking various questions about the language used in different situations. Such an approach would be inappropriate for a Census." Thus, although it was acknowledged that the "inclusion of such a Census question would undoubtedly raise the profile of Scots", no question about Scots was, in the end, included in the 2001 Census.[11][12][13]

A practical snag with the attempts to institutionalise a single variety of Scots, especially for official use, is that it incorporates vocabulary from literary Scots (e.g. the use of "ken", meaning "know", which still occurs colloquially in many Eastern dialects but is entirely absent in others such as Glaswegian). An example is the Scots-language home page of the Scottish Parliament.[14]

[edit] Language change

After the Union of Scotland and England, the issue of language became topical, and foremost was the question of whether Scottish people should speak standard English or Scots[citation needed]. Gaelic was never considered an option; at the time, it was mostly relegated to the Highlands and Islands. Scots became considered to have a substratal relationship to English, as opposed to an adstratal relationship.

On one hand, well-off Scots took to learning English through such activities as those of the Thomas Sheridan who in 1761 gave a series of lectures on English elocution. Charging a guinea at a time (about £65 in today's money), they were attended by over 300 men, and he was made a freeman of the City of Edinburgh. Following this, some of the city's intellectuals formed the Select Society for Promoting the Reading and Speaking of the English Language in Scotland. Other people who scorned Scotticisms included intellectuals from the Scottish Enlightenment like David Hume and Adam Smith who went to great lengths to get rid of every Scotticism from their writings.[15] This was not universally welcomed, as was illustrated by the summary by F. Pottle, James Boswell's 20th century biographer, concerning James' view of speech habits of his father Alexander Boswell, a judge of the supreme courts of Scotland : He scorned modern literature, spoke broad Scots from the bench, and even in writing took no pains to avoid the Scotticisms which most of his colleagues were coming to regard as vulgar.

On the other hand, the education system also became increasingly geared to teaching English, though this was initially impaired by the teachers' and students' lack of knowledge of English pronunciation through lack of contact with English speakers. Aspects of English grammar and lexis could be accessed through printed texts. By the 1840s the Scottish Education Department's language policy was that Scots had no value "...it is not the language of 'educated' people anywhere, and could not be described as a suitable medium of education or culture". Students, of course, reverted to Scots outside the classroom, but the reversion was not complete. What occurred, and has been occurring ever since, is a process of language attrition, whereby successive generations have adopted more and more features from English. This process has accelerated rapidly since wide-spread access to mass media in English, and increased population mobility, became available after the Second World War. It has recently taken on the nature of wholesale language shift. These processes are often erroneously referred to as language change, convergence or merger.[weasel words][citation needed] Residual features of Scots are often regarded as slang.

[edit] Literature

Examples of the first English literature include the Lord's Prayer in Northumbrian Anglo-Saxon from c. 650, which begins "Faeder ure, Thu the eart on heofonum". Some Scottish and Northumbrian folk still say "oor faither" and "thoo art".[citation needed]

Among the earliest Scots literature is John Barbour's Brus (fourteenth century), Wyntoun's Cronykil and Blind Harry's Wallace (fifteenth century). From the fifteenth century, much literature based around the Royal Court in Edinburgh and the University of St Andrews was produced by writers such as Robert Henryson, William Dunbar, Douglas and David Lyndsay. The Complaynt of Scotland was an early printed work in Scots.

After the seventeenth century, anglicisation increased. At the time, many of the oral ballads from the borders and the North East were written down. Writers of the period were Robert Sempill, Robert Sempill the younger, Francis Sempill, Lady Wardlaw and Lady Grizel Baillie.

In the eighteenth century, writers such as Allan Ramsay, Robert Burns, Robert Fergusson and Walter Scott continued to use Scots. Scott introduced vernacular dialogue to his novels. Other well-known authors like Robert Louis Stevenson, William Alexander, George MacDonald, J. M. Barrie and other members of the Kailyard school like Ian Maclaren also wrote in Scots or used it in dialogue.

In the Victorian era popular Scottish newspapers regularly included articles and commentary in the vernacular, often of unprecedented proportions.[16] Ian Maclaren and others of the

In the early twentieth century, a renaissance in the use of Scots occurred, its most vocal figure being Hugh MacDiarmid whose benchmark poem A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle (1926) did much to demonstrate the power of Scots as a modern idiom. Other contemporaries were Douglas Young, John Buchan, Sidney Goodsir Smith, Robert Garioch and Robert McLellan. However, the revival was largely limited to verse and other literature.

In 1983 William Laughton Lorimer's translation of the New Testament from the original Greek was published.

Highly anglicised Scots is sometimes used in contemporary fiction, for example, the Edinburgh dialect of Scots in Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh (later made into a motion picture of the same name).

But'n'Ben A-Go-Go by Matthew Fitt is a cyberpunk novel written entirely in what Wir Ain Leid (Our Own Language) calls "General Scots". Like all cyberpunk work, it contains imaginative neologisms.

The strip cartoons Oor Wullie and The Broons in the Sunday Post use some Scots.

[edit] Dialects

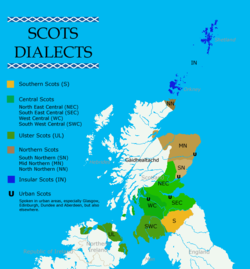

There are at least five Scots dialects:

- Insular Scots, spoken in Orkney and Shetland.

- Northern Scots, spoken north of Dundee, often split into North Northern, Mid Northern—also known as North East Scots and referred to as "the Doric"—and South Northern.

- Central Scots, spoken from Fife and Perthshire to the Lothians and Wigtownshire, often split into North East and South East Central, West Central and South West Central Scots.

- South Scots or simply the "Border Tongue" or "Borders' Dialect" spoken in the Border areas.

- Ulster Scots, spoken by the descendants of Scottish settlers (and also some with Irish and English descent) in littoral Northern Ireland and County Donegal in The Republic of Ireland, and sometimes described by the neologism "Ullans", a conflation of Ulster and Lallans. However, in a recent article, Caroline Macafee, editor of The Concise Ulster Dictionary, stated that Ulster Scots was "clearly a dialect of Central Scots".

The southern extent of Scots may be identified by the range of a number of pronunciation features which set Scots apart from neighbouring English dialects. The Scots pronunciation of come [kʌm] becomes [kum] in Northern English. The Scots realisation [kʌm] reaches as far south as the mouth of the north Esk in north Cumbria, crossing Cumbria and skirting the foot of the Cheviots before reaching the east coast at Bamburgh some 12 miles north of Alnwick. The Scots[x]-English[∅]/[f] cognate group (micht-might, eneuch-enough, etc) can be found in a small portion of north Cumbria with the southern limit stretching from Bewcastle to Longtown and Gretna. The Scots pronunciation of wh as /ʍ/ becomes English /w/ south of Carlisle but remains in Northumberland, but Northumberland realises “r” as /ʁ/, often called the burr, which is not a Scots realisation. Thus the greater part of the valley of the Esk and the whole of Liddesdale can be considered to be northern English dialects rather than Scots ones. From the 19th century onwards influence from the South through education and increased mobility have caused Scots features to retreat northwards so that for all practical purposes the political and linguistic boundaries may be considered to coincide.[17]

Northeast English, spoken throughout the traditional counties of Northumberland and County Durham, shares other features with Scots which have not been described above.

As well as the main dialects, Edinburgh, Dundee and Glasgow (see Glasgow patter) have local variations on an Anglicised form of Central Scots. In Aberdeen, Mid Northern Scots is spoken by a minority. Due to them being roughly near the border between the two dialects, places like Dundee and Perth can contain elements and influences of both Northern and Central Scots.

[edit] Spelling

By the middle of the 17th century contemporary southern English had replaced Middle Scots for normal transactional writing. The 18th century revival of written Scots was based largely on contemporary colloquial Scots generally using highly anglicised spellings although some conventions inherited from previous centuries remained in use. The orthographic conventions of this literary or ‘pan-dialectal’ Scots were diaphonemic rather than phonetic in nature, subsuming varying dialect realisations, although dialect spellings became more frequent later in the period. This tradition embodied by writers such as Allan Ramsay, Robert Fergusson, Robert Burns, Sir Walter Scott, Charles Murray, David Herbison, James Orr, James Hogg and William Laidlaw among others, is well described in Grant and Dixon’s 1921 Manual of Modern Scots.

During the 20th century a number of proposals for spelling reform were presented. Commenting on this, John Corbett (2003: 260) writes that "devising a normative orthography for Scots has been one of the greatest linguistic hobbies of the past century." Most proposals entailed regularising the use of established 18th and 19th century conventions, in particular the avoidance of apostrophes where they supposedly represent "missing" English letters. Such letters were never actually missing in Scots. For example, in the 14th century, Barbour spelt the Scots cognate of 'taken' as tane. Since there has been no k in the word for over 700 years, representing its omission with an apostrophe seems pointless. The current spelling is usually taen.

Through the 20th century, with the decline of spoken Scots and knowledge of the literary tradition, phonetic (often humorous) representations became more common.

[edit] Sounds

The following is a guide for readers. How the spellings are applied in practice is beyond the scope of such a short description. Phonetics are in IPA.

[edit] Consonants

Most consonants are usually pronounced much as in English but:

- c: /k/ or /s/, much as in English.

- ch: /x/, also gh. Medial 'cht' may be /ð/ in Northern dialects. loch (fjord or lake), nicht (night), dochter (daughter), dreich (dreary), etc. Similar to the German "Nacht".

- ch: word initial or where it follows 'r' /tʃ/. airch (arch), mairch (march), etc.

- gn: /n/. In Northern dialects /gn/ may occur.

- kn: /n/. In Northern dialects /kn/ or /tn/ may occur. knap (talk), knee, knowe (knoll), etc.

- ng: is always /ŋ/.

- nch: usually /nʃ/. brainch (branch), dunch (push), etc.

- r: /r/ or /ɹ/ is pronounced in all positions, i.e. rhotically.

- s or se: /s/ or /z/.

- t: may be a glottal stop between vowels or word final. In Ulster dentalised pronunciations may also occur, also for 'd'.

- th: /ð/ or /θ/ much as is English. Initial 'th' in thing, think and thank, etc. may be /h/.

- wh: usually /ʍ/, older /xʍ/. Northern dialects also have /f/.

- wr: /wr/ more often /r/ but may be /vr/ in Northern dialects. wrack (wreck), wrang (wrong), write, wrocht (worked), etc.

- z: /jɪ/ or /ŋ/, may occur in some words as a substitute for the older <ȝ> (yogh). For example: brulzie (broil), gaberlunzie (a beggar) and the names Menzies, Finzean, Culzean, MacKenzie etc. (As a result of the lack of education in Scots, MacKenzie is now generally pronounced with a /z/ following the perceived realisation of the written form, as more controversially is sometimes Menzies.)

[edit] Silent letters

- The word final 'd' in nd and ld: but often pronounced in derived forms. Sometimes simply 'n' and 'l' or 'n'' and 'l''. auld (old), haund (hand), etc.

- 't' in medial cht: ('ch' = /x/) and st and before final en. fochten (fought), thristle (thistle) also 't' in aften (often), etc.

- 't' in word final ct and pt but often pronounced in derived forms. respect, accept, etc.

[edit] Vowels

In Scots, vowel length is usually conditioned by the Scots vowel length rule. Words which differ only slightly in pronunciation from Scottish English are generally spelled as in English. Other words may be spelt the same but differ in pronunciation, for example: aunt, swap, want and wash with /a/, bull, full v. and pull with /ʌ/, bind, find and wind v., etc. with /ɪ/.

- The unstressed vowel /ə/ may be represented by any vowel letter.

- a: usually /a/ but in south west and Ulster dialects often /ɑ/. Note final a in awa (away), twa (two) and wha (who) may also be /ɑ/ or /ɔ/ or /e/ depending on dialect.

- au, aw and sometimes a, a' or aa: /ɑː/ or /ɔː/ in Southern, Central and Ulster dialects but /aː/ in Northern dialects. The cluster 'auld' may also be /ʌul/ in Ulster. aw (all), cauld (cold), braw (handsome), faw (fall), snaw (snow), etc.

- ae, ai, a(consonant)e: /e/. Often /ɛ/ before /r/. In Northern dialects the vowel in the cluster -'ane' is often /i/. brae (slope), saip (soap), hale (whole), ane (one), ance (once), bane (bone), etc.

- ea, ei, ie: /iː/ or /eː/ depending on dialect. /ɛ/ may occur before /r/. Root final this may be /əi/ in Southern dialects. In the far north /əi/ may occur. deid (dead), heid (head), meat (food), clear, speir (enquire), sea, etc.

- ee, e(Consonant)e: /iː/. Root final this may be /əi/ in Southern dialects. ee (eye), een (eyes), steek (shut), here, etc.

- e: /ɛ/. bed, het (heated), yett (gate), etc.

- eu: /(j)u/ or /(j)ʌ/ depending on dialect. Sometimes erroneously 'oo', 'u(consonant)e', 'u' or 'ui'. beuk (book), eneuch (enough), ceuk (cook), leuk (look), teuk (took), etc.

- ew: /ju/. In Northern dialects a root final 'ew' may be /jʌu/. few, new, etc.

- i: /ɪ/, but often varies between /ɪ/ and /ʌ/ especially after 'w' and 'wh'. /æ/ also occurs in Ulster before voiceless consonants. big, fit (foot), wid (wood), etc.

- i(consonant)e, y(consonant)e, ey: /əi/ or /aɪ/. 'ay' is usually /e/ but /əi/ in ay (yes) and aye (always). In Dundee it is noticeably /ɛ/.

- o: /ɔ/ but often /o/.

- oa: /o/.

- ow, owe (root final), seldom ou: /ʌu/. Before 'k' vocalisation to /o/ may occur especially in western and Ulster dialects. bowk (retch), bowe (bow), howe (hollow), knowe (knoll), cowp (overturn), yowe (ewe), etc.

- ou, oo, u(consonant)e: /u/. Root final /ʌu/ may occur in Southern dialects. cou (cow), broun (brown), hoose (house), moose (mouse) etc.

- u: /ʌ/. but, cut, etc.

- ui, also u(consonant)e, oo: /ø/ in conservative dialects. In parts of Fife, Dundee and north Antrim /e/. In Northern dialects usually /i/ but /wi/ after /g/ and /k/ and also /u/ before /r/ in some areas eg. fuird (ford). Mid Down and Donegal dialects have /i/. In central and north Down dialects /ɪ/ when short and /e/ when long. buird (board), buit (boot), cuit (ankle), fluir (floor), guid (good), schuil (school), etc. In central dialects uise v. and uiss n. (use) are [jeːz] and [jɪs].

[edit] Grammar

Not all of the following features are exclusive to Scots and may also occur in English.

[edit] Definite article

The is used before the names of seasons, days of the week, many nouns, diseases, trades and occupations, sciences and academic subjects. It is also often used in place of the indefinite article and instead of a possessive pronoun: the hairst (autumn), the Wadensday (Wednesday), awa ti the kirk (off to church), the nou (at the moment), the day (today), the haingles (influenza), the Laitin (Latin), The deuk ett the bit breid (The duck ate a piece of bread), the wife (my wife) etc.

[edit] Nouns

Nouns usually form their plural in -(e)s but some irregular plurals occur: ee/een (eye/eyes), cauf/caur (calf/calves), horse/horse (horse/horses), cou/kye (cow/cows), shae/shuin (shoe/shoes). Nouns of measure and quantity unchanged in the plural: fower fit (four feet), twa mile (two miles), five pund (five pounds), three hunderwecht (three hundredweight). Regular plurals include laifs (loaves), leafs (leaves), shelfs (shelves) and wifes (wives).

[edit] Diminutives

Diminutives in -ie, burnie small burn (stream), feardie/feartie (frightened person, coward), gamie (gamekeeper), kiltie (kilted soldier), postie (postman), wifie (woman), rhodie (rhododendron), and also in -ock, bittock (little bit), playock (toy, plaything), sourock (sorrel) and Northern –ag, bairnag (little), bairn (child), Cheordag (Geordie), -ockie, hooseockie (small house), wifeockie (little woman), both influenced by the Scottish Gaelic diminutive -ag (-óg in Irish Gaelic).

[edit] Modal verbs

The modal verbs mey (may), ocht tae (ought to), and sall (shall), are no longer used much in Scots but occurred historically and are still found in anglicised literary Scots. Can, shoud (should), and will are the preferred Scots forms. Scots employs double modal constructions He'll no can come the day (He won't be able to come today), A micht coud come the morn (I may be able to come tomorrow), A uised tae coud dae it, but no nou (I used to be able to do it, but not now).

[edit] Present tense of verbs

The present tense of verbs adhere to the Northern subject rule whereby verbs end in -s in all persons and numbers except when a single personal pronoun is next to the verb, Thay say he's ower wee, Thaim that says he's ower wee, Thir lassies says he's ower wee (They say he's too small), etc. Thay're comin an aw but Five o thaim's comin, The lassies? Thay've went but Ma brakes haes went. Thaim that comes first is serred first (Those who come first are served first). The trees growes green in the simmer (The trees grow green in summer).

Wis 'was' may replace war 'were', but not conversely: You war/wis thare.

[edit] Past tense and past participle of verbs

The regular past form of the verb is -it, -t or -ed, according to the preceding consonant or vowel:

- hurtit, skelpit (smacked), mendit;

- traivelt (travelled), raxt (reached), telt (told), kent (knew/known);

- cleaned, scrieved (scribbled), speired (asked), dee'd (died).

Many verbs have forms which are distinctive from English (two forms connected with ~ means that they are variants):

- bite/bate/bitten (bite/bit/bitten), drive/drave/driven~dreen (drive/drove/driven), ride/rade/ridden (ride/rode/ridden), rive/rave/riven (rive/rived/riven), rise/rase/risen (rise/rose/risen), slide/slade/slidden (slide/slid/slid), slite/slate/slitten (slit/slit/slit), write/wrate/written or vrit/vrat/vrutten (write/wrote/written);

- bind/band/bund (bind/bound/bound), clim/clam/clum (climb/climbed/climbed), find/fand/fund (find/found/found), fling/flang/flung (fling/flung/flung), hing/hang/hung (hang/hung/hung), rin/ran/run (run/ran/run), spin/span/spun (spin/spun/spun), stick/stack/stuck (stick/stuck/stuck), drink/drank/drukken~drunk (drink/drank/drunk);

- creep/crap/cruppen (creep/crept/crept), greet/grat/grutten (weep/wept/wept), sweit/swat/swutten (sweat/sweat/sweat), weet/wat/wutten (wet/wet/wet), pit/pat/putten~pitten (put/put/put), sit/sat/sutten~sitten (sit/sat/sat), spit/spat/sputten~spitten (spit/spat/spat);

- brek~brak/brak/brokken~brakken (break/broke/broken), get~git/gat/gotten (get/got/got[ten]), speak/spak/spoken (speak/spoke/spoken), fecht/focht/fochten (fight/fought/fought);

- beir/buir~bore/born(e) (bear/bore/borne), sweir/swuir~swore/sworn (swear/swore/sworne), teir/tuir~tore/torn (tear/tore/torn), weir/wuir~wore/worn (wear/wore/worn);

- cast/cuist/casten~cuisten (cast/cast/cast), lat/luit/latten~luitten (let/let/let), staund/stuid/stuiden (stand/stood/stood), fesh/fuish/feshen~fuishen (fetch/fetched), thrash/thruish/thrashen~thruishen (thresh/threshed/threshed), wash/wuish/washen~wuishen (wash/washed/washed);

- bake/bakit~beuk/bakken (bake/baked/baked), lauch/leuch/lauchen~leuchen (laugh/laughed/laughed), shak/sheuk/shakken~sheuken (shake/shook/shaken), tak/teuk/taen (take/took/taken);

- gae/gaed/gane (go/went/gone), gie/gied/gien (give/gave/given), hae/haed/haen (have/had/had);

- chuse/chusit/chusit (choose/chose/chosen), soom/soomed/soomed (swim/swam/swum), sell/selt~sauld/selt~sauld (sell/sold/sold), tell/telt~tauld/telt~tauld (tell/told/told), cut/cuttit/cuttit (cut/cut/cut), hurt/hurtit/hurtit (hurt/hurt/hurt), keep/keepit/keepit (keep/kept/kept), sleep/sleepit/sleepit (sleep/slept/slept).

[edit] Word order

Scots prefers the word order He turnt oot the licht to 'He turned the light out' and Gie me it to 'Give it to me'.

Certain verbs are often used progressively He wis thinkin he wad tell her, He wis wantin tae tell her.

Verbs of motion may be dropped before an adverb or adverbial phrase of motion A'm awa tae ma bed, That's me awa hame, A'll intae the hoose an see him.

[edit] Ordinal numbers

Ordinal numbers end mostly in t: seicont, fowert, fift, saxt— (second, fourth, fifth, sixth) etc., but note also first, thrid/third— (first, third).

[edit] Adverbs

Adverbs are usually of the same form as the verb root or adjective especially after verbs. Haein a real guid day (Having a really good day). She's awfu fauchelt (She's awfully tired).

Adverbs are also formed with -s, -lies, lins, gate(s)and wey(s) -wey, whiles (at times), mebbes (perhaps), brawlies (splendidly), geylies (pretty well), aiblins (perhaps), airselins (backwards), hauflins (partly), hidlins (secretly), maistlins (almost), awgates (always, everywhere), ilkagate (everywhere), onygate (anyhow), ilkawey (everywhere), onywey(s) (anyhow, anywhere), endweys (straight ahead), whit wey (how, why).

[edit] Subordinate clauses

Verbless subordinate clauses introduced by an (and) express surprise or indignation. She haed tae walk the hale lenth o the road an her sieven month pregnant (and she seven months pregnant). He telt me tae rin an me wi ma sair leg (and me with my sore leg).

[edit] Negation

Negation occurs by using the adverb no, in the North East nae, as in A'm no comin (I'm not coming), A'll no learn ye (I will not teach you), or by using the suffix -na (pronunciation depending on dialect), as in A dinna ken (I don't know), Thay canna come (They can't come), We coudna hae telt him (We couldn't have told him), and A hivna seen her (I haven't seen her). The usage with no is preferred to that with -na with contractable auxiliary verbs like -ll for will, or in yes no questions with any auxiliary He'll no come and Did he no come?

[edit] Relative pronoun

The relative pronoun is that ('at is an alternative form borrowed from Norse but can also be arrived at by contraction) for all persons and numbers, but may be left out Thare's no mony fowk (that) leeves in that glen (There aren't many people who live in that glen). The anglicised forms wha, wham, whase 'who, whom, whose', and the older whilk 'which' are literary affectations; whilk is only used after a statement He said he'd tint it, whilk wis no whit we wantit tae hear. The possessive is formed by adding 's or by using an appropriate pronoun The wifie that's hoose gat burnt (the woman whose house was burnt), the wumman that her dochter gat mairit (the woman whose daughter got married); the men that thair boat wis tint (the men whose boat was lost).

A third adjective/adverb yon/yonder, thon/thonder indicating something at some distance D'ye see yon/thon hoose ower yonder/thonder? Also thae (those) and thir (these), the plurals of that and this respectively.

In Northern Scots this and that are also used where "these" and "those" would be in Standard English.

[edit] Suffixes

- Negative na: /ɑ/, /ɪ/ or /e/ depending on dialect. Also 'nae' or 'y' eg. canna (can't), dinna (don't) and maunna (mustn't).

- fu (ful): /u/, /ɪ/, /ɑ/ or /e/ depending on dialect. Also 'fu'', 'fie', 'fy', 'fae' and 'fa'.

- The word ending ae: /ɑ/, /ɪ/ or /e/ depending on dialect. Also 'a', 'ow' or 'y', for example: arrae (arrow), barrae (barrow) and windae (window), etc.

[edit] See also

- Billy Kay

- Dictionary of the Scots Language

- Doric

- Lallans

- Languages in the United Kingdom

- Phonological history of the Scots language

- Scotticism

- Scottish Corpus of Texts and Speech

- Scottish English

- Scottish literature

[edit] Notes

- ^ A.J. Aitken in The Oxford Companion to the English Language, Oxford University Press 1992.

- ^ Nostra Vulgari Lingua: Scots as a European Language 1500 - 1700 By Dr. Dauvit Horsbroch

- ^ Second Report submitted by the United Kingdom pursuant to article 25, paragraph 1 of the framework convention for the protection of national minorities Available here

- ^ See for example Confession of Faith Ratification Act 1560, written in Scots and still part of British Law

- ^ Jones, Charles (1995) A Language Suppressed: The Pronunciation of the Scots Language in the 18th Century, Edinburgh, John Donald, p.vii

- ^ Jones, Charles (1995) A Language Suppressed: The Pronunciation of the Scots Language in the 18th Century, Edinburgh, John Donald, p.2

- ^ Eagle, Andy (2006) Aw Ae Wey - Written Scots in Scotland and Ulster. Available at http://www.scots-online.org/airticles/AwAeWey.pdf

- ^ Exposed to ridicule Scotsman 7 February 2004

- ^ Scots - Teaching approaches Learning and Teaching Scotland Online Service

- ^ National Guidelines 5-14: ENGLISH LANGUAGE Learning and Teaching Scotland Online Service

- ^ (PDF)The Scots Language in education in Scotland. Mercator-Education. 2002. ISSN 1570-1239. http://www1.fa.knaw.nl./mercator/regionale_dossiers/PDFs/scots_in_scotland.PDF.

- ^ T. G. K. Bryce and Walter M. Humes (2003). Scottish Education. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 263–264. ISBN 074861625X.

- ^ Jane Stuart-Smith (2004). "Scottish English: phonology". in Bernd Kortmann and Edgar W. Schneider. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 48–49. ISBN 3110175320.

- ^ The Scottish Parliament: - Languages - Scots

- ^ http://www.scuilwab.org.uk/14PlusNew/TheHistoryOScots.pdf Scuilwab

- ^ William Donaldson, The Language of the People: Scots Prose from the Victorian Revival, Aberdeen University Press 1989.

- ^ SND Introduction - Phonetic Description of Scottish Language and Dialects

[edit] References

- Corbett, John; McClure, Derrick; Stuart-Smith, Jane (Editors)(2003) The Edinburgh Companion to Scots. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1596-2

- Dieth, Eugen (1932) A Grammar of the Buchan Dialect (Aberdeenshire). Cambridge, W. Heffer & Sons Ltd.

- Eagle, Andy (2005) Wir Ain Leid. Scots-Online. Available in full at http://www.scots-online.org/airticles/WirAinLeid.pdf

- Gordon Jr., Raymond G.(2005), editor The Ethnologue Fifteenth Edition. SCI. ISBN 1-55671-159-X. Available in full at http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=sco

- Grant, William; Dixon, James Main (1921) Manual of Modern Scots. Cambridge, University Press.

- Jones, Charles (1997) The Edinburgh History of the Scots Language. Edinburgh, University of Edinburgh Press. ISBN 0-7486-0754-4

- Jones, Charles (1995) A Language Suppressed: The pronunciation of the Scots language in the 18th century. Edinburgh, John Donald. ISBN 0-85976-427-3

- Kay, Billy (1986) Scots, The Mither Tongue. London, Grafton Books. ISBN 0-586-20033-9

- Kingsmore, Rona K. (1995) Ulster Scots Speech: A Sociolinguistic Study. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-0711-7

- MacAfee, Caroline (1980/1992) Characteristics of Non-Standard Grammar in Scotland (University of Aberdeen: available at http://www.abdn.ac.uk/~enl038/grammar.htm)

- McClure, J. Derrick (1997) Why Scots Matters. Edinburgh, Saltire Society. ISBN 0-85411-071-2

- McKay, Girvan (2007) The Scots Tongue, Polyglot Publications, Tullamore, Ireland & Lulu Publications, N. Carolina.

- Murray, James A. H. (1873) The Dialect of the Southern Counties of Scotland, Transactions of the Philological Society, Part II, 1870-72. London-Berlin, Asher & Co.

- Niven, Liz; Jackson, Robin (Eds.) (1998) The Scots Language: its place in education. Watergaw Publications. ISBN 0-9529978-5-1

- Robertson, T. A.; Graham, John J. (1952, ²1991) Grammar and Use of the Shetland Dialect. Lerwick, The Shetland Times Ltd.

- Ross, David; Smith, Gavin D. (Editors)(1999) Scots-English, English-Scots Practical Dictionary. New York, Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-7818-0779-4

- Scottish National Dictionary Association (1929–1976) The Scottish National Dictionary. Designed partly on regional lines and partly on historical principles, and containing all the Scottish words known to be in use or to have been in use since c. 1700. Ed. by William Grant and David D. Murison, vol. I–X Edinburgh.

- Scottish National Dictionary Association (1999) Concise Scots Dictionary . Edinburgh, Polygon. ISBN 1-902930-01-0

- Scottish National Dictionary Association (1999) Scots Thesaurus. Edinburgh, Polygon. ISBN 1-902930-03-7

- Smith, the Rev. William Wye The four Gospels in braid Scots, Paisley 1924

- Warrack, Alexander (Editor)(1911) Chambers Scots Dictionary. Chambers.

- Wettstein, Paul (1942) The Phonology of a Berwickshire Dialect. Biel, Schüler S. A.

- Wilson, James (1915) Lowland Scotch as Spoken in the Lower Strathearn District of Perthshire. London, Oxford University Press.

- Wilson, James (1923) The Dialect of Robert Burns as Spoken in Central Ayrshire. London, Oxford University Press.

- Wilson, James (1926) The Dialects of Central Scotland [Fife and Lothian]. London, Oxford University Press.

- Yound, C.P.L. (2004) Scots Grammar. Scotsgate. Available in full at http://www.scotsgate.com/scotsgate01.pdf

- Zai, Rudolf (1942) The Phonology of the Morebattle Dialect, East Roxburghshire. Lucerne, Räber & Co.

[edit] External links

| This article's external links may not follow Wikipedia's content policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive or inappropriate external links. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Scots language |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of |

- Scots-online

- The Scots Language Society

- Scots Language Centre

- The Linguist List, Eastern Michigan University and Wayne State University

- Scots at Omniglot

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), 2005. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online

- Dictionary of the Scottish Language – Phonetic Description of Scottish Language and Dialects

- Words Without Borders Peter Constantine: Scots: The Auld an Nobill Tung

[edit] Dictionaries and linguistic information

- The Dictionary of the Scots Language

- Scottish Language Dictionaries Ltd.

- Dialect Map

- SAMPA for Scots

- Scottish words - illustrated

- Abstract: Vowel height harmony and blocking in Buchan Scots, Mary Paster, University of California, Phonology Vol. 21, Issue 3

- - Scots Language Recordings

[edit] Education

[edit] Collections of texts

- ScotsteXt - books, poems and texts in Scots

- A Tait Wanchancie - a collection of texts

- Scottish Corpus of Texts & Speech - Multimedia corpus of Scots and Scottish English

- BBC Voices, Scots section - The BBC Voices Project is a major though informal look at UK language and speech

|

|||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||