Babylon

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Ancient Mesopotamia |

|---|

| Euphrates · Tigris |

|

Empires / Cities

|

| Sumer |

| Eridu · Kish · Uruk · Ur Lagash · Nippur · Ngirsu |

| Elam |

| Susa |

| Akkadian Empire |

| Akkad · Mari |

| Amorites |

| Isin · Larsa |

| Babylonia |

| Babylon · Chaldea |

| Assyria |

| Assur · Nimrud Dur-Sharrukin · Nineveh |

| Mesopotamia |

| Sumer (king list) |

| Kings of Assyria Kings of Babylon |

| Enûma Elish · Gilgamesh |

| Assyro-Babylonian religion |

| Sumerian · Elamite |

| Akkadian · Aramaic |

| Hurrian · Hittite |

Babylon was a city-state of ancient Mesopotamia, sometimes considered an empire, the remains of which can be found in present-day Al Hillah, Babil Province, Iraq, about 85 kilometers (55 mi) south of Baghdad. All that remains of the original ancient famed city of Babylon today is a mound, or tell, of broken mud-brick buildings and debris in the fertile Mesopotamian plain between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, in Iraq. Although it has been reconstructed. Historical resources inform us that Babylon was at first a small town, that had sprung up by the beginning of the third millennium BCE (the dawn of the dynasties). The town flourished and attained prominence and political repute with the rise of the first Babylonian dynasty. It was the "holy city" of Babylonia by approximately 2300 BCE, and the seat of the Neo-Babylonian Empire from 612 BCE. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

The form Babylon is the Greek variant of Akkadian Babilu (bāb-ilû, meaning "Gateway of the god(s)", translating Sumerian Ka.dingir.ra). In the Hebrew Bible, the name appears as בבל (Babel), interpreted by Book of Genesis 11:9 to mean "confusion" (of languages), from the verb balbal, "to confuse".

Contents |

[edit] History

The earliest source to mention Babylon may be a dated tablet of the reign of Sargon of Akkad (ca. 24th century BCE short chronology). The so-called "Weidner Chronicle" states that it was Sargon himself who built Babylon "in front of Akkad" (ABC 19:51). Another chronicle likewise states that Sargon "dug up the dirt of the pit of Babylon, and made a counterpart of Babylon next to Agade". (ABC 20:18-19).

Some scholars, including linguist I.J. Gelb, have suggested that the name Babil is an echo of an earlier city name. According to Ranajit Pal, this city was in the East[1]. Herzfeld wrote about Bawer in Iran, which was allegedly founded by Jamshid; the name Babil could be an echo of Bawer. David Rohl holds that the original Babylon is to be identified with Eridu. The Bible in Genesis 10 indicates that Nimrod was the original founder of Babel (Babylon). Joan Oates claims in her book Babylon that the rendering "Gateway of the gods" is no longer accepted by modern scholars.

Over the years, the power and population of Babylon waned. From around the 20th century BCE, it was occupied by Amorites, nomadic tribes from the west who were Semitic speakers like the Akkadians, but did not practice agriculture like them, preferring to herd sheep.

[edit] Old Babylonian period

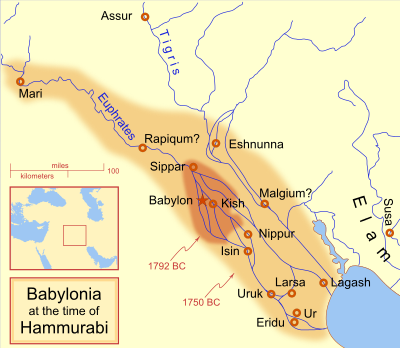

The First Babylonian Dynasty was established by Sumu-abum, but the city-state controlled little surrounding territory until it became the capital of Hammurabi's empire (ca. 18th century BCE). Subsequently, the city continued to be the capital of the region known as Babylonia — although during the almost 400 years of domination by the Kassites (1530–1155 BCE), the city was renamed Karanduniash.

Hammurabi is also known for codifying the laws of Babylonia into the Code of Hammurabi that has had a lasting influence on legal thought.

The city itself was built upon the Euphrates, and divided in equal parts along its left and right banks, with steep embankments to contain the river's seasonal floods. Babylon grew in extent and grandeur over time, but gradually became subject to the rule of Assyria.

It has been estimated that Babylon was the largest city in the world from ca. 1770 to 1670 BCE, and again between ca. 612 and 320 BCE. It was perhaps the first city to reach a population above 200,000.[2]

[edit] Assyrian period

During the reign of Sennacherib of Assyria, Babylonia was in a constant state of revolt, led by Mushezib-Marduk, and suppressed only by the complete destruction of the city of Babylon. In 689 BCE, its walls, temples and palaces were razed, and the rubble was thrown into the Arakhtu, the sea bordering the earlier Babylon on the south. This act shocked the religious conscience of Mesopotamia; the subsequent murder of Sennacherib was held to be in expiation of it, and his successor Esarhaddon hastened to rebuild the old city, to receive there his crown, and make it his residence during part of the year. On his death, Babylonia was left to be governed by his elder son Shamash-shum-ukin, who eventually headed a revolt in 652 BCE against his brother in Nineveh, Assurbanipal.

Once again, Babylon was besieged by the Assyrians and starved into surrender. Assurbanipal purified the city and celebrated a "service of reconciliation", but did not venture to "take the hands" of Bel. In the subsequent overthrow of the Assyrian Empire, the Babylonians saw another example of divine vengeance. (Albert Houtum-Schindler, "Babylon," Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th ed.)

[edit] Neo-Babylonian Chaldean Empire

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2008) |

This image is a candidate for speedy deletion. It may be deleted after seven days from the date of nomination.

Under Nabopolassar, Babylon threw off the Assyrian rule in 626 BC and became the capital of the Neo-Babylonian Chaldean Empire.[3][4][5]

With the recovery of Babylonian independence, a new era of architectural activity ensued, and his son Nebuchadnezzar II (604–561 BCE) made Babylon into one of the wonders of the ancient world.[6] Nebuchadnezzar ordered the complete reconstruction of the imperial grounds, including rebuilding the Etemenanki ziggurat and the construction of the Ishtar Gate — the most spectacular of eight gates that ringed the perimeter of Babylon. The Ishtar Gate survives today in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. Nebuchadnezzar is also credited with the construction of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon (one of the seven wonders of the ancient world), said to have been built for his homesick wife Amyitis. Whether the gardens did exist is a matter of dispute. Although excavations by German archaeologist Robert Koldewey are thought to reveal its foundations, many historians disagree about the location, and some believe it may have been confused with gardens in Nineveh.

[edit] Persia captures Babylon

In 539 BCE, the Neo-Babylonian Empire fell to Cyrus the Great, king of Persia, with an unprecedented military maneuver. The famed walls of Babylon were indeed impenetrable, with the only way into the city through one of its many gates or through the Euphrates, which ebbed beneath its thick walls. Metal gates at the river's in-flow and out-flow prevented underwater intruders, if one could hold one's breath to reach them. Cyrus (or his generals) devised a plan to use the Euphrates as the mode of entry to the city, ordering large camps of troops at each point and instructed them to wait for the signal. Awaiting an evening of a national feast among Babylonians (generally thought to refer to the feast of Belshazzar mentioned in Daniel V), Cyrus' troops diverted the Euphrates river upstream, causing the Euphrates to drop to about 'mid thigh level on a man' or to dry up altogether. The soldiers marched under the walls through thigh-level water or as dry as mud. The Persian Army conquered the outlying areas of the city's interior while a majority of Babylonians at the city center were oblivious to the breach. The account was elaborated upon by Herodotus,[7] and is also mentioned by passages in the Hebrew Bible.[8][9] Cyrus claimed the city by walking through the gates of Babylon with little or no resistance from the drunken Babylonians.

Cyrus later issued a decree permitting captive people, including the Jews, to return to their own land (as explained in the Old Testament), to allow their temple to be rebuilt back in Jerusalem.

Under Cyrus and the subsequent Persian king Darius the Great, Babylon became the capital city of the 9th Satrapy (Babylonia in the south and Athura in the north), as well as a centre of learning and scientific advancement. In Achaemenid Persia, the ancient Babylonian arts of astronomy and mathematics were revitalised and flourished, and Babylonian scholars completed maps of constellations. The city was the administrative capital of the Persian Empire, the preeminent power of the then known world, and it played a vital part in the history of that region for over two centuries. Many important archaeological discoveries have been made that can provide a better understanding of that era.[10][11]

The early Persian kings had attempted to maintain the religious ceremonies of Marduk, but by the reign of Darius III, over-taxation and the strains of numerous wars led to a deterioration of Babylon's main shrines and canals, and the disintegration of the surrounding region. Despite three attempts at rebellion in 522 BCE, 521 BCE and 482 BCE, the land and city of Babylon remained solidly under Persian rule for two centuries, until Alexander the Great's entry in 331 BCE.

[edit] Hellenistic period

In 331 BCE, Darius III was defeated by the forces of the Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great at the Battle of Gaugamela, and in October, Babylon fell to the young conqueror. A native account of this invasion notes a ruling by Alexander not to enter the homes of its inhabitants.[12]

Under Alexander, Babylon again flourished as a centre of learning and commerce. But following Alexander's death in 323 BCE in the palace of Nebuchadnezzar, his empire was divided amongst his generals, and decades of fighting soon began, with Babylon once again caught in the middle.

The constant turmoil virtually emptied the city of Babylon. A tablet dated 275 BCE states that the inhabitants of Babylon were transported to Seleucia, where a palace was built, as well as a temple given the ancient name of Esagila. With this deportation, the history of Babylon comes practically to an end,[citation needed] though more than a century later, it was found that sacrifices were still performed in its old sanctuary. By 141 BCE, when the Parthian Empire took over the region, Babylon was in complete desolation and obscurity.

[edit] Persian Empire period

Under the Parthian, and later, Sassanid Persians, Babylon remained a province of the Persian Empire for nine centuries, until about 650 CE. It continued to have its own culture and peoples, who spoke varieties of Aramaic, and who continued to refer to their homeland as Babylon. Some examples of their cultural products are often found in the Babylonian Talmud, the Mandaean religion, and the religion of the prophet Mani.

[edit] Archaeology of Babylon

Historical knowledge of Babylon's topography is derived from classical writers, the inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar, and several excavations, including those of the Deutsche Orientgesellschaft begun in 1899. The layout is that of the Babylon of Nebuchadnezzar; the older Babylon destroyed by Sennacherib having left few, if any, traces behind.

Most of the existing remains lie on the east bank of the Euphrates, the principal ones being three vast mounds: the Babil to the north, the Qasr or "Palace" (also known as the Mujelliba) in the centre, and the Ishgn "Amran ibn" All, with the outlying spur of the Jumjuma, to the south. East of these come the Ishgn el-Aswad or "Black Mound" and three lines of rampart, one of which encloses the Babil mound on the north and east sides, while a third forms a triangle with the southeast angle of the other two. West of the Euphrates are other ramparts, and the remains of the ancient Borsippa.

We learn from Herodotus and Ctesias that the city was built on both sides of the river in the form of a square, and was enclosed within a double row of lofty walls, or a triple row according to Ctesias. Ctesias describes the outermost wall as 360 stades (68 kilometers/42 mi) in circumference, while according to Herodotus it measured 480 stades (90 kilometers/56 mi), which would include an area of about 520 square kilometers (200 sq mi).

The estimate of Ctesias is essentially the same as that of Q. Curtius (v. I. 26) — 368 stades — and Cleitarchus (ap. Diod. Sic. ii. 7) — 365 stades; Strabo (xvi. 1. 5) makes it 385 stades. But even the estimate of Ctesias, assuming the stade to be its usual length, would imply an area of about 260 square kilometers (100 sq mi). According to Herodotus, the width of the walls was 24 m.

[edit] Reconstruction

In 1985, Saddam Hussein started rebuilding the city on top of the old ruins (because of this, artifacts and other finds may well be under the city by now), investing in both restoration and new construction. He inscribed his name on many of the bricks in imitation of Nebuchadnezzar. One frequent inscription reads: "This was built by Saddam Hussein, son of Nebuchadnezzar, to glorify Iraq". This recalls the ziggurat at Ur, where each individual brick was stamped with "Ur-Nammu, king of Ur, who built the temple of Nanna". These bricks became sought after as collectors' items after the downfall of Hussein, and the ruins are no longer being restored to their original state. He also installed a huge portrait of himself and Nebuchadnezzar at the entrance to the ruins, and shored up Processional Way, a large boulevard of ancient stones, and the Lion of Babylon, a black rock sculpture about 2,600 years old.

When the Gulf War ended, Saddam wanted to build a modern palace, also over some old ruins; it was made in the pyramidal style of a Sumerian ziggurat. He named it Saddam Hill. In 2003, he was ready to begin the construction of a cable car line over Babylon when the invasion began and halted the project.

An article published in April 2006 states that UN officials and Iraqi leaders have plans for restoring Babylon, making it into a cultural center. [13][14]

[edit] Effects of the U.S. military

US forces were criticised for building the military base "Camp Alpha", comprising among others a helipad on ancient Babylonian ruins following the 2003 invasion of Iraq, under the command of General James T. Conway of the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force.

US forces have occupied the site for some time and have caused damage to the archaeological record. In a report of the British Museum's Near East department, Dr. John Curtis describes how parts of the archaeological site were levelled to create a landing area for helicopters, and parking lots for heavy vehicles. Curtis wrote that the occupation forces

- "caused substantial damage to the [replica of the] Ishtar Gate, one of the most famous monuments from antiquity [...] US military vehicles crushed 2,600-year-old brick pavements, archaeological fragments were scattered across the site, more than 12 trenches were driven into ancient deposits and military earth-moving projects contaminated the site for future generations of scientists [...] Add to all that the damage caused to nine of the moulded brick figures of dragons in the Ishtar Gate by soldiers trying to remove the bricks from the wall."

A US Military spokesman claimed that engineering operations were discussed with the "head of the Babylon museum". [15]

The head of the Iraqi State Board for Heritage and Antiquities, Donny George, said that the "mess will take decades to sort out".[16] In April 2006, Colonel John Coleman, former chief of staff for the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force, offered to issue an apology for the damage done by military personnel under his command. However he claimed that the US presence had deterred far greater damage from other looters.[17] Some antiquities were removed since creation of Camp Alpha, without doubt to be sold on the antiquities market, which is booming since the beginning of the occupation of Iraq[18].

[edit] Further reading

- Joan Oates, Babylon, [Ancient Peoples and Places], Thames and Hudson, 1986. ISBN 0-500-02095-7 (hardback) ISBN 0-500-27384-7 (paperback)

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- [1] This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- [2] informationclearinghouse.info/article11389.htm What I heard about Iraq in 2005 by Eliot Weinberger,London Review of Books

- [3] The Ancient Middle Eastern Capital City — Reflection and Navel of the World by Stefan Maul ("Die altorientalische Hauptstadt — Abbild und Nabel der Welt," in Die Orientalische Stadt: Kontinuität. Wandel. Bruch. 1 Internationales Kolloquium der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft. 9.-1 0. Mai 1996 in Halle/Saale, Saarbrücker Druckerei und Verlag (1997), p.109-124.

- [4] A military history of Mesopotamia

[edit] Notes

- ^ A New Non-Jonesian History Of The World

- ^ Rosenberg, Matt T. Largest Cities Through History, About.com. Accessed April 19, 2008.

- ^ Bradford, Alfred S. (2001). With Arrow, Sword, and Spear: A History of Warfare in the Ancient World, pp. 47-48. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0275952592.

- ^ Curtis, Adrian; Herbert Gordon May (2007). Oxford Bible Atlas Oxford University Press ISBN 978-0191001581 p. 122 "chaldean+empire"&num=100

- ^ von Soden, Wilfred; Donald G. Schley (1996). William B. Eerdmanns ISBN 978-0802801425 p. 60 "chaldean+empire"&num=100#PPA60,M1 (

- ^ Saggs, H.W.F. (2000). Babylonians, p. 165. University of California Press. ISBN 0520202228.

- ^ Herodotus, Book 1, Section 191

- ^ Isaiah 44:27

- ^ Jeremiah 50-51

- ^ Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia The British Museum. Accessed April 19, 2008.

- ^ Mesopotamia: The Persians

- ^ Beck, Roger B.; Linda Black, Larry S. Krieger, Phillip C. Naylor, Dahia Ibo Shabaka, (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

- ^ Gettleman, Jeffrey. Unesco intends to put the magic back in Babylon, International Herald Tribune, April 21, 2006. Accessed April 19, 2008.

- ^ McBride, Edward. Monuments to Self: Baghdad's grands projects in the age of Saddam Hussein, MetropolisMag. Accessed April 19, 2008.

- ^ "Damage seen to ancient Babylon". The Boston Globe. January 16, 2005. http://www.boston.com/news/world/middleeast/articles/2005/01/16/damage_seen_to_ancient_babylon/.

- ^ Heritage News from around the world, World Heritage Alert!. Accessed April 19, 2008.

- ^ Cornwell, Rupert. US colonel offers Iraq an apology of sorts for devastation of Babylon, The Independent, April 15, 2006. Accessed April 19, 2008.

- ^ J. E. Curtis, « Report on Meeting at Babylon 11 – 13 December 2004 », British Museum, 2004 [1]

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Babylon |

- Babylon wrecked by war, The Guardian, January 15, 2005

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, Babylon

- History lost in dust of war-torn Iraq, BBC, April 25, 2005, mentions damage to Babylon.

- reggae babylon, Babylon's usage in Reggae music

- US marines offer Babylon damage apology, by Jonathan Charles BBC World Affairs correspondent, 14 April 2006

- Mirosław Olbryś, The Polish contribution to protection of the archaeological heritage in central south Iraq, November 2003 to April 2005, Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, Volume 8, Number 2, 2007 , pp. 88-104(17)