Epic of Gilgamesh

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article includes a list of references or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations where appropriate. (January 2009) |

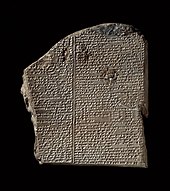

The Epic of Gilgamesh is an epic poem from Ancient Mesopotamia and is among the earliest known works of literary fiction. Scholars believe that it originated as a series of Sumerian legends and poems about the mythological hero-king Gilgamesh, which were gathered into a longer Akkadian poem much later; the most complete version existing today is preserved on 12 clay tablets in the library collection of the 7th century BCE Assyrian king Ashurbanipal. It was originally titled He who Saw the Deep (Sha naqba īmuru) or Surpassing All Other Kings (Shūtur eli sharrī). Gilgamesh might have been a real ruler in the late Early Dynastic II period (ca. 27th century BCE).[1]

The essential story revolves around the relationship between Gilgamesh, who has become distracted and disheartened by his rule, and a friend, Enkidu, who is half-wild and who undertakes dangerous quests with Gilgamesh. Much of the epic focuses on Gilgamesh's thoughts of loss following Enkidu's death. It is about their becoming human together, and has a high emphasis on immortality. A large portion of the poem illustrates Gilgamesh's search for immortality after Enkidu's death.

The epic is widely read in translation, and the hero, Gilgamesh, has become an icon of popular culture.

Contents |

[edit] History

Many original and distinct sources exist over a 2,000 year timeframe, but only the oldest and those from a late period have yielded significant enough finds to enable a coherent intro-translation. Therefore, the old Sumerian version, and a later Akkadian version, which is now referred to as the standard edition, are the most frequently referenced. The standard edition is the basis of modern translations, and the old version only supplements the standard version when the lacunae—or gaps in the cuneiform tablet—are great. (Note that revised versions based on new information have been coming out periodically over the last decades, and the epic is not considered complete, even now.)

The earliest Sumerian versions of the epic date from as early as the Third Dynasty of Ur (2150-2000 BCE) (Dalley 1989: 41-42). The earliest Akkadian versions are dated to the early second millennium (Dalley 1989: 45). The "standard" Akkadian version, consisting of twelve tablets, was edited by Sin-liqe-unninni sometime between 1300 and 1000 BC and was found in the library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is widely known today. The first modern translation of the epic was in the 1880s by George Smith.[2] More recent translations into English include one undertaken with the assistance of the American novelist John Gardner, and John Maier, published in 1984. In 2001, Benjamin Foster produced a reading in the Norton Critical Edition Series that fills in many of the blanks of the standard edition with previous material. The most definitive standard edition is the carefully edited two volume critical work by Andrew George. This represents the fullest treatment of the standard edition material, and he discusses at length the archaeological state of the material, provides a tablet by tablet exegesis, and furnishes a dual language side by side translation. George's translation was also published in a general reader edition under the Penguin Classics imprint in 2003. In 2004, Stephen Mitchell released a controversial edition, which is his interpretation of previous scholarly translations into what he calls "a new English version".[citation needed]

The discovery of artifacts (ca. 2600 BC) associated with Enmebaragesi of Kish, who is mentioned in the legends as the father of one of Gilgamesh's adversaries, has lent credibility to the historical existence of Gilgamesh (Dalley 1989: 40-41).[3]

[edit] Standard version

The standard version was discovered by Austen Henry Layard in the library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh in 1849. It was written in standard Babylonian, a dialect of Akkadian that was only used for literary purposes. This version was compiled by Sin-liqe-unninni sometime between 1300 and 1000 BC out of older legends.

The standard Akkadian and earlier Sumerian versions are differentiated based on the opening words, or incipit. The older version begins with the words "Surpassing all other kings", while the standard version's incipit is "He who saw the deep" (ša nagbu amāru). The Akkadian word nagbu, "deep", is probably to be interpreted here as referring to "unknown mysteries".[citation needed] However, Andrew George believes that it refers to the specific knowledge that Gilgamesh brought back from his meeting with Uta-Napishti (Utnapishtim): he gains there knowledge of the realm of Ea, whose cosmic realm is seen as the fountain of wisdom (George 1999: L [pg. 50 of the introduction]). In general, interpreters feel that Gilgamesh was given knowledge of how to worship the gods, of why death was ordained for human beings, of what makes a good king, and of the true nature of how to live a good life. Utnapishtim, the hero of the Flood myth tells his story to Gilgamesh, which is related to the Babylonian Epic of Atrahasis.

The twelfth tablet is appended to the epic representing a sequel to the original eleven, and was most probably added at a later date. This tablet has commonly been omitted until recent years. It has the startling narrative inconsistency of introducing Enkidu alive, and bears seemingly little relation to the well-crafted and finished 11 tablet epic; indeed, the epic is framed around a ring structure in which the beginning lines of the epic are quoted at the end of the 11th tablet to give it at the same time circularity and finality. Tablet 12 is actually a near copy of an earlier tale, in which Gilgamesh sends Enkidu to retrieve some objects of his from the Underworld, but Enkidu dies and returns in the form of a spirit to relate the nature of the Underworld to Gilgamesh—an event which seems to many superfluous given Enkidu's dream of the underworld in Tablet VII.[4]

[edit] Content of the tablets

The story starts with an introduction of Gilgamesh of Uruk, the greatest king on earth, two-thirds god and one-third human, as the strongest King-God who ever existed. The introduction describes his glory and praises the brick city walls of Uruk. The people in the time of Gilgamesh, however, are not happy. They complain that he is too harsh and abuses his power by sleeping with women before their husbands do, so the goddess of creation Aruru creates the wild-man Enkidu. Enkidu starts bothering the shepherds. When one of them complains to Gilgamesh, the king sends the woman Shamhat who was a temple prostitute—a nadītu or hierodule in Greek. The body contact with Shamhat civilizes Enkidu, and after six days and seven nights, he is no longer a wild beast who lives with animals. Meanwhile, Gilgamesh has some strange dreams; his mother Rimat Ninsun explains them by telling him that a mighty friend will come to him.

Enkidu and Shamhat leave the wilderness for Uruk to attend a wedding. When Gilgamesh comes to the party to sleep with the bride, he finds his way blocked by Enkidu. Enkidu and Gilgamesh fight each other. After a mighty battle, Gilgamesh breaks off from the fight (or defeats Enkidu in other versions, this portion is missing from the Standard Babylonian version but is supplied from other versions).

Gilgamesh proposes to travel to the Cedar Forest to cut some great trees and kill the demon Humbaba for their glory. Enkidu objects but can not convince his friend. They seek the wisdom of the Elder Council, but Gilgamesh remains stubborn. Enkidu gives in and both prepare to journey to Cedar Forest. Gilgamesh tells his mother, who complains about it, but then asks the sun-god Shamash for support and gives Enkidu some advice. She also adopts Enkidu as her second son.

Gilgamesh and Enkidu journey to the Cedar Forest. On the way, Gilgamesh has five bad dreams, but due to the bad construction of the tablet, they are hard to reconstruct. Enkidu, each time, explains the dreams as a good omen. When they reach the forest Enkidu becomes afraid again and Gilgamesh has to encourage him.

When the heroes finally run into Humbaba, the demon-ogre guardian of the trees, the monster starts to offend them. This time, Gilgamesh is the one to become afraid. After some brave words of Enkidu, the battle commences. Their rage separates the Syria mountains from Lebanon. Finally, Shamash sends his 13 winds to help the two heroes, and Humbaba is defeated. The monster begs Gilgamesh for his life, and Gilgamesh pities the creature. Enkidu, however, gets mad with Gilgamesh and asks him to kill the beast. Humbaba then turns to Enkidu and begs him to persuade his friend to spare his life. When Enkidu repeats his request to Gilgamesh, Humbaba curses them both before Gilgamesh puts an end to it. When the two heroes cut a huge cedar tree, Enkidu makes a huge door of it for the gods and lets it float down the river.

Gilgamesh rejects the sexual advances of Anu (the sky-god)'s daughter, the goddess Ishtar (goddess of love and war), because of her mistreatment of her previous lovers like Dumuzi. Ishtar asks her father Anu to send the "Bull of Heaven" to avenge the rejected sexual advances. When Anu rejects her complaints, Ishtar threatens to raise the dead. Anu becomes scared and gives in. The bull of heaven is a plague for the lands. Apparently the creature has something to do with drought because, according to the epic, the water disappeared and the vegetation died. Whatever the case, Gilgamesh and Enkidu, this time without divine help, slay the beast and offer its heart to Shamash. When they hear Ishtar cry out in agony, Enkidu tears off the bull's hindquarter and throws it in her face and threatens her. The city of Uruk celebrates, but Enkidu has a bad dream detailed in the next tablet.

In the dream of Enkidu, the gods decide that somebody has to be punished for killing the Bull of Heaven and Humbaba, and in the end they decide to punish Enkidu. All of this is much against the will of Shamash. Enkidu tells Gilgamesh all about it, then curses the door he made for the gods. Gilgamesh is shocked and goes to temple to pray to Shamash for the health of his friend. Enkidu then starts to curse the trapper and Shamhat because now he regrets the day that he became human. Shamash speaks from heaven and points out how unfair Enkidu is; he also tells him that Gilgamesh will become a shadow of his former self because of his death. Enkidu regrets his curses and blesses Shamhat. He becomes more and more ill and describes the Netherworld as he is dying.

Gilgamesh delivers a lamentation for Enkidu, offering gifts to the many gods, in order that he might walk beside Enkidu in the netherworld.

Gilgamesh sets out to avoid Enkidu's fate and makes a perilous journey to visit Utnapishtim and his wife, the only humans to have survived the Great Flood and who were granted immortality by the gods, in the hope that he too can attain immortality. Along the way, Gilgamesh passes the two mountains from where the sun rises, which are guarded by two scorpion-beings. They allow him to proceed, and he travels through the dark where the sun travels every night. Just before the sun is about to catch up with him, he reaches the end. The land at the end of the tunnel is a wonderland full of trees with leaves of jewels.

Gilgamesh meets the alewife Siduri and tells her the purpose of his journey. Siduri attempts to dissuade him from his quest but sends him to Urshanabi the ferryman to help him cross the sea to Utnapishtim. Urshanabi is in the company of some stone-giants. Gilgamesh considers them hostile and kills them. When he tells Urshanabi his story and asks for help, he is told that he just killed the only creatures able to cross the Waters of Death. The waters of death are not to be touched, so Urshanabi commands him to cut 300 trees and fashion them into oars so that they can cross the waters by picking a new oar each time. Finally they reach the island of Utnapishtim. Utnapishtim sees that there is someone else in the boat, and asks Gilgamesh who he is. Gilgamesh tells him his story and asks for help, but Utnapishtim reprimands him because fighting the fate of humans is futile and ruins the joy in life.

Gilgamesh argues that Utnapishtim is not different from him and asks him his story, and why he has a different fate. Utnapishtim tells him about the great flood. His story is a summary of the story of Atrahasis (see also Gilgamesh flood myth) but skips the previous plagues sent by the gods. He reluctantly offers Gilgamesh a chance for immortality, but questions why the gods would give the same honour as himself, the flood hero, to Gilgamesh and challenges Gilgamesh to stay awake for six days and seven nights first. However, just when Utnapishtim finishes his words Gilgamesh falls asleep. Utnapishtim ridicules the sleeping Gilgamesh in the presence of his wife and tells her to bake a loaf of bread for every day he is asleep so that Gilgamesh cannot deny his failure. When Gilgamesh, after seven days, discovers his failure, Utnapishtim is furious with him and sends him back to Uruk with Urshanabi in exile. The moment that they leave, Utnapishtim's wife asks her husband to have mercy on Gilgamesh for his long journey. Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh of a plant at the bottom of the ocean that will make him young again. Gilgamesh obtains the plant by binding stones to his feet so he can walk the bottom of the sea. He does not trust the plant and plans to test it on an old man's back when he returns to Uruk. Unfortunately he places the plant on the shore of a lake while he bathes, and it is stolen by a serpent who loses his old skin and thus is reborn. Gilgamesh weeps in the presence of Urshanabi. Having failed at both opportunities, he returns to Uruk, where the sight of its massive walls prompts him to praise this enduring work to Urshanabi.

Note that the content of the last tablet is not connected with previous ones. Gilgamesh complains to Enkidu that his ball-game-toys fell in the underworld. Enkidu offers to bring them back. Delighted, Gilgamesh tells Enkidu what he must and must not do in the underworld in order to come back. Enkidu forgets the advice and does everything he was told not to do. The underworld keeps him. Gilgamesh prays to the gods to give him his friend back. Enlil and Suen don’t bother to reply but Ea and Shamash decide to help. Shamash cracks a hole in the earth and Enkidu jumps out of it. The tablet ends with Gilgamesh questioning Enkidu about what he has seen in the underworld. The story doesn’t make clear whether Enkidu reappears only as a ghost or really comes alive again.

[edit] Old-Babylonian version

All tablets except for the second and third are from different origins than the above, so this summary is made up out of different versions.

- Tablet missing

- Gilgamesh tells his mother Ninsun about two nightmares he had. His mother explains that they mean that a friend will come to Uruk. In the meanwhile Enkidu and his woman (here called Shamshatum) are making love. She civilizes him in company of the shepherds by offering him human food. Enkidu helps the shepherd by guarding the sheep. They go to Uruk to marry but Gilgamesh wants to use his privileges to sleep with Shamshatum first. Enkidu and Gilgamesh battle but Gilgamesh breaks off the fight. Enkidu praises Gilgamesh as a special person.

- The tablet is broken here but it seems that Gilgamesh has offered the plan to go the Pine Forest to cut trees and kill Humbaba. Enkidu protests, he knows Humbaba and is aware of his power. Gilgamesh talks Enkidu into it with some words of encouragement but Enkidu remains reluctant. They start preparation and call for the elders. The elders also protest but after Gilgamesh talks to them they wish him good luck.

- 1(?) tablet missing

- Fragments from the two different versions/tablets that tell how Enkidu encourages Gilgamesh to slay Humbaba. When Gilgamesh does so they cut some trees and find the dwellings of the Annunaki. Enkidu cuts a door of wood for Enlil and let it float down the Euphrates.

- Tablets missing

- Gilgamesh argues with Shamash the futility of his quest. The tablet is damaged. We then find Gilgamesh talking with Siduri about his quest and his travel to Ut-Napishtim (here called Uta-na’ishtim). Siduri also questions his goals. Another hole in the text. Gilgamesh has smashed the stone creatures and talks to the ferryman Urshanabi (here called Sur-sunabu). After a short discussion Sur-sunabu asks Gilgamesh to cut 300 oars so that they may cross the waters of dead without the stone creatures. The rest of the tablet is damaged.

- Tablet(s)

[edit] Sumerian version

There are five extant stories from the Sumerian version of the Gilgamesh epic cycle:

- Gilgamesh and Huwawa (version A translation, version B translation) (Corresponds to the Cedar Forest episode (tablets 3-5) in the Akkadian version.)

- Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven (translation) (Corresponds to the Bull of Heaven episode (tablet 6) in the Akkadian version. The Bull's voracious appetite causes drought and hardship in the land.)

- Gilgamesh and Aga (translation) (Gilgamesh vs. Aga of Kish, no correspondence with the Akkadian version.)

- Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld (translation) (Corresponds to tablet 12 in the Akkadian version.)

- The Death of Gilgamesh (translation) (This is the story of Gilgamesh's, rather than Enkidu's death. The Sumerian flood hero, Zi-ud-sura, is invoked, but only as a contrast between the flood hero who saved life and was giving eternal life in return, and the mortal Gilgamesh.

[edit] Influence on later epic literature

According to the Greek scholar Ioannis Kakridis, there are a large number of parallel verses as well as themes or episodes which indicate a substantial influence of the Epic of Gilgamesh on the Odyssey, the Greek epic poem ascribed to Homer.[5]

Some aspects of the Gilgamesh flood myth seem to be related to the story of Noah's ark in the Bible; see deluge (mythology).

The Alexander the Great myth in Islamic and Syrian cultures is also considered to be influenced by the Gilgamesh story[6] [7]. Alexander wanders through a region of darkness and terror in search of the water of life. He faces strange encounters, reaches the water but, like Gilgamesh, fails to become immortal.

[edit] See also

- List of artifacts significant to the Bible

- Sumerian literature

- Babylonian literature

- Atra-Hasis

- Sumerian creation myth

- Deluge (mythology)

- Gilgamesh in popular culture

- Gilgamesh flood myth

- Translation

- Poetry

[edit] In music

Czech composer Bohuslav Martinu composed an oratorio after this epic, completed in 1955.

[edit] In popular culture

| Lists of miscellaneous information should be avoided. Please relocate any relevant information into appropriate sections or articles. (December 2008) |

- In the "Star Trek: The Next Generation" episode "Darmok", Captain Picard gives Dathon a basic synopsis of this story.

- Gilgamesh and Enkidu are shown to have survived to the present day, and serve as adversaries to the similarly revived King Arthur, in the 2003 Peter David fantasy novel "One Knight Only", the second book of his "Knight" trilogy.

- In the Final Fantasy video game series, Gilgamesh appears as a recurring 8-armed character, first appearing in Final Fantasy V as a recurring villain, then in various later games and remakes of earlier games as an optional boss or summon spell. He is sometimes accompanied by a dog-like creature named Enkidu and wields various recognisable swords from other games in the series. Humbaba also appears as an enemy in Japanese Final Fantasy VI (Originally released as Final Fantasy III in the U.S.) as a large green monster with the powers of wind and great strength.

- In the popular eroge Fate/stay night, Gilgamesh appears as a powerful villain. He references many parts of the Epic, even at one point saying "Immortality? I gave that to the snake." as an aside.

- Robert Silverberg wrote a novel based upon the story that gave naturalistic explanations of all the supernatural elements of the original.

- In the Half Life video game series, one alien quotes "Our greatest poet once wrote: Gilga Gilgamesh gaga"

- Earlier than all the previous examples: Wilson Tucker's novel of 1953: Time Masters, on which Gilgamesh is presented as an alien with much longer life span than humans, living in the present times as a private investigator. The "water for life" is presented as water containing deuterium, or "heavy water".

[edit] Notes

- ^ Gilgamesh (translated from the Sin-Leq-Unninnt version) by John Gardner and John Maier w/ assistance from Robert Henshaw ISBN 0-394-74089-0(pbk) p.4

- ^ Smith, George (1872-12-03). "The Chaldean Account of the Deluge" (HTML). Sacred-Texts.com. http://www.sacred-texts.com/ane/chad/index.htm.

- ^ Dalley, Stephanie, Myths from Mesopotamia, Oxford University Press, 1989

- ^ MythHome: Gilgamesh the 12th Tablet

- ^ Ioannis Kakridis: "Eisagogi eis to Omiriko Zitima" (Introduction to the Homeric Question) In: Omiros: Odysseia. Edited with translation and comments by Zisimos Sideris, Daidalos Press, I. Zacharopoulos Athens.

- ^ Jastrow M.The religion of Babylonia and Assyria.GIN & COMPANY. Boston 1898

- ^ Sattari J. Astudy on the epic of Gilgamesh and the legend of Alexander. Markaz Publications 2001 (In Persian)

[edit] Bibliography

[edit] Editions

- Dalley, Stephanie, trans. (1991). Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192817892.

- George, Andrew R., trans. & edit. (2003). The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts. England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198149220.

- George, Andrew R., trans. & edit. (1999, reprinted with corrections 2003). The Epic of Gilgamesh. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-044919-1.

- Foster, Benjamin R., trans. & edit. (2001). The Epic of Gilgamesh. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-97516-9.

- Kovacs, Maureen Gallery, transl. with intro. (1985,1989). The Epic of Gilgamesh. Stanford University Press: Stanford, California. ISBN 0-8047-1711-7. Glossary, Appendices, Appendix (Chapter XII=Tablet XII). A line-by-line translation (Chapters I-XI).

- Jackson, Danny (1997). The Epic of Gilgamesh. Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 0-86516-352-9.

- Mason, Herbert (2003). Gilgamesh: A Verse Narrative. Boston: Mariner Books. ISBN 978-0618275649. First published in 1970 by Houghton Mifflin; Mentor Books paperback published 1972.

- Mitchell, Stephen (2004). Gilgamesh: A New English Version. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-7432-6164-X.

- Sandars, N. K. (2006). The Epic of Gilgamesh (Penguin Epics). ISBN 0141026286 - re-print of the Penguin Classic translation (in prose) by N. K. Sandars 1960 (ISBN 014044100X) without the introduction.

- Parpola, Simo, with Mikko Luuko, and Kalle Fabritius (1997). The Standard Babylonian, Epic of Gilgamesh. The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project. ISBN 951-45-7760-4 (Volume 1) in the original Akkadian cuneiform and transliteration; commentary and glossary are in English.

- Ferry, David (1993). Gilgamesh: A New Rendering in English Verse. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0374523835.

[edit] Other

- Damrosch, David (2007). The Buried Book: The Loss and Rediscovery of the Great Epic of Gilgamesh. United States of America: Henry Holt and Co.. pp. 315. ISBN 0-80508-029-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=6jJQLrJXrakC&pg=PP1&dq=%22The+Buried+Book:+The+Loss+and+Rediscovery+of+the+Great+Epic+of+Gilgamesh%22&num=100&client=opera&sig=ACfU3U19bQtV0FbzQHz00tu38-cpnaTj3g.

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (1976). The Treasures of Darkness, A History of Mesopotamian Religion. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-01844-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=pD17nsgWQBoC&dq=%22The+Treasures+of+Darkness,+A+History+of+Mesopotamian+Religion%22&pg=PP1&ots=xIB1vOkUgr&sig=48BSBQDrKwEWbD_1_tlIU7hkc0Y&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result.

- Tigay, Jeffrey H. (1982). The Evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812278054. http://books.google.com/books?id=HzYOAAAAYAAJ&q=%22The+Evolution+of+the+Gilgamesh+Epic%22&dq=%22The+Evolution+of+the+Gilgamesh+Epic%22&num=100&client=opera&pgis=1.

- West, Martin Litchfield (1997). The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth. New York, New York: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-815042-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=wuHeHQAACAAJ&dq=%22The+East+Face+of+Helicon%22&num=100&client=opera.

[edit] External links

- Translations of the legends of Gilgamesh in the Sumerian language can be found in Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Fluckiger-Hawker, E, Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998-.

- The Project Gutenberg eBook, An Old Babylonian Version of the Gilgamesh Epic, by Anonymous, Edited by Morris Jastrow, Translated by Albert T. Clay

- Epic of Gilgamesh, summary by M. McGoodwin

- Gilgamesh by Richard Hooker (wsu.edu)

- The Epic of Gilgamesh: A Spiritual Biography

- Lectures on the Gilgamesh epic by Clay Burell. A very personal but interesting approach.