Colossus of Rhodes

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Colossus of Rhodes was a statue of the Greek god Helios, erected on the Greek island of Rhodes by Chares of Lindos between 292 and 280 BC. It is considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Before its destruction, the Colossus of Rhodes stood over 30 meters (107 ft) high, making it one of the tallest statues of the ancient world.[1]

Contents |

Siege of Rhodes

Alexander the Great of Macedonia died at an early age in 323 BC without having had time to put into place any plans for his succession. Fighting broke out among his generals, the Diadochi, with four of them eventually dividing up much of his empire in the Mediterranean area. During the fighting, Rhodes had sided with Ptolemy, and when Ptolemy eventually took control of Egypt, Rhodes and Ptolemaic Egypt formed an alliance which controlled much of the trade in the eastern Mediterranean.

Antigonus I Monophthalmus was upset by this turn of events. In 305 BC he had his son Demetrius Poliorcetes, also a general, invade Rhodes with an army of 40,000; however, the city was well defended, and Demetrius—whose name "Poliorcetes" signifies the "besieger of cities"—had to start construction of a number of massive siege towers in order to gain access to the walls. The first was mounted on six ships, but these capsized in a storm before they could be used. He tried again with a larger, land-based tower named Helepolis, but the Rhodian defenders stopped this by flooding the land in front of the walls so that the rolling tower could not move.

In 304 BC a relief force of ships sent by Ptolemy arrived, and Demetrius's army abandoned the siege, leaving most of their siege equipment. To celebrate their victory, the Rhodians sold the equipment left behind for 300 talents[2] (roughly US$360 million in today's money) and decided to use the money to build a colossal statue of their patron god, Helios. Construction was left to the direction of Chares, a native of Lindos in Rhodes, who had been involved with large-scale statues before. His teacher, the sculptor Lysippos, had constructed a 22 meter (70 ft) high[3] bronze statue of Zeus at Tarentum.

Construction

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2007) |

Ancient accounts, which differ to some degree, describe the structure as being built with iron tie bars to which brass plates were fixed to form the skin. The interior of the structure, which stood on a 15 meters (50 ft) high white marble pedestal near the Mandraki harbor entrance, was then filled with stone blocks as construction progressed.[4] Other sources place the Colossus on a breakwater in the harbor. The statue itself was over 30 meters (107 ft) tall. Much of the iron and bronze was reforged from the various weapons Demetrius's army left behind, and the abandoned second siege tower was used for scaffolding around the lower levels during construction. Upper portions were built with the use of a large earthen ramp. During the building, workers would pile mounds of dirt on the sides of the colossus. Upon completion all of the dirt was removed and the colossus was left to stand alone. After twelve years, in 280 BC, the statue was completed. Preserved in Greek anthologies of poetry is what is believed to be the genuine dedication text for the Colossus.[5]

To you, o Sun, the people of Dorian Rhodes set up this bronze statue reaching to Olympus, when they had pacified the waves of war and crowned their city with the spoils taken from the enemy. Not only over the seas but also on land did they kindle the lovely torch of freedom and independence. For to the descendants of Herakles belongs dominion over sea and land.

Possible construction method

Modern engineers have put forward a plausible hypothesis for the statue construction, based on the technology of those days (which was not based on the modern principles of earthquake engineering), and the accounts of Philo and Pliny who both saw and described the remains .[6]

The base pedestal was at least 60 feet (18 m) in diameter and either circular or octagonal. The feet were carved in stone and covered with thin bronze plates riveted together. Eight forged iron bars set in a radiating horizontal position formed the ankles and turned up to follow the lines of the legs while becoming progressively smaller. Individually cast curved bronze plates 60 inches (1,500 mm) square with turned in edges were joined together by rivets through holes formed during casting to form a series of rings. The lower plates were 1-inch (25 mm) in thickness to the knee and 3/4 inch thick from knee to abdomen, while the upper plates were 1/4 to 1/2 inch thick except where additional strength was required at joints such as the shoulder, neck, etc. The legs would need to be filled at least to the knees with stones for stability. Accounts described earthen mounds used to aid construction; however, to reach the top of the statue would have required a mound 300 feet (91 m) in diameter, which exceeded the available land area, so modern engineers have proposed that the abandoned siege towers stripped down would have made efficient scaffolding.

A computer simulation of this construction indicated that an earthquake would have caused a cascading failure of the rivets, causing the statue to break up at the joints while still standing instead of breaking after falling to the ground, as described in second hand accounts. The arms would have been first to separate, followed by the legs. The knees were less likely to break and the ankles' survival would have depended on the quality of the workmanship.

Destruction

The statue stood for only 56 years until Rhodes was hit by an earthquake in 226 BC. The statue snapped at the knees and fell over on to the land. Ptolemy III offered to pay for the reconstruction of the statue, but the oracle of Delphi made the Rhodians afraid that they had offended Helios, and they declined to rebuild it. The remains lay on the ground as described by Strabo (xiv.2.5) for over 800 years, and even broken, they were so impressive that many traveled to see them. Pliny the Elder remarked that few people could wrap their arms around the fallen thumb and that each of its fingers was larger than most statues.[7]

In 654, an Arab force under Muslim caliph Muawiyah I captured Rhodes, and according to the chronicler Theophanes the Confessor,[8] the remains were sold to a "Jewish merchant of Edessa". The buyer had the statue broken down, and transported the bronze scrap on the backs of 900 camels to his home. There is compelling evidence, however, that all traces of the Colossus had actually disappeared long before the Arab invasion. Theophanes is the sole source of this story to which all other sources can be traced. The stereotypical Arab destruction and the purported sale to a Jew probably originated as a powerful metaphor for Nebuchadnezzar's dream of the destruction of a great and awesome statue, and would have been understood by any seventh century monk as evidence for the coming apocalypse.[9] The same story is recorded by Barhebraeus, writing in syriac in the 13th century in Edessa (see E.A. Wallis Budge, The Chronography of Gregory Abu'l-Faraj, vol I, p. 98, APA - Philo Press, Amsterdam, 1932): (After the Arab pillage of Rhodes) "And a great number of men hauled on strong ropes which were tied round the brass Colossus which was in the city and pulled it down. And they weighed from it three thousand loads of Corinthian brass, and they sold it to a certain Jew from Emesa" (that is the Syrian city of Homs).

Posture

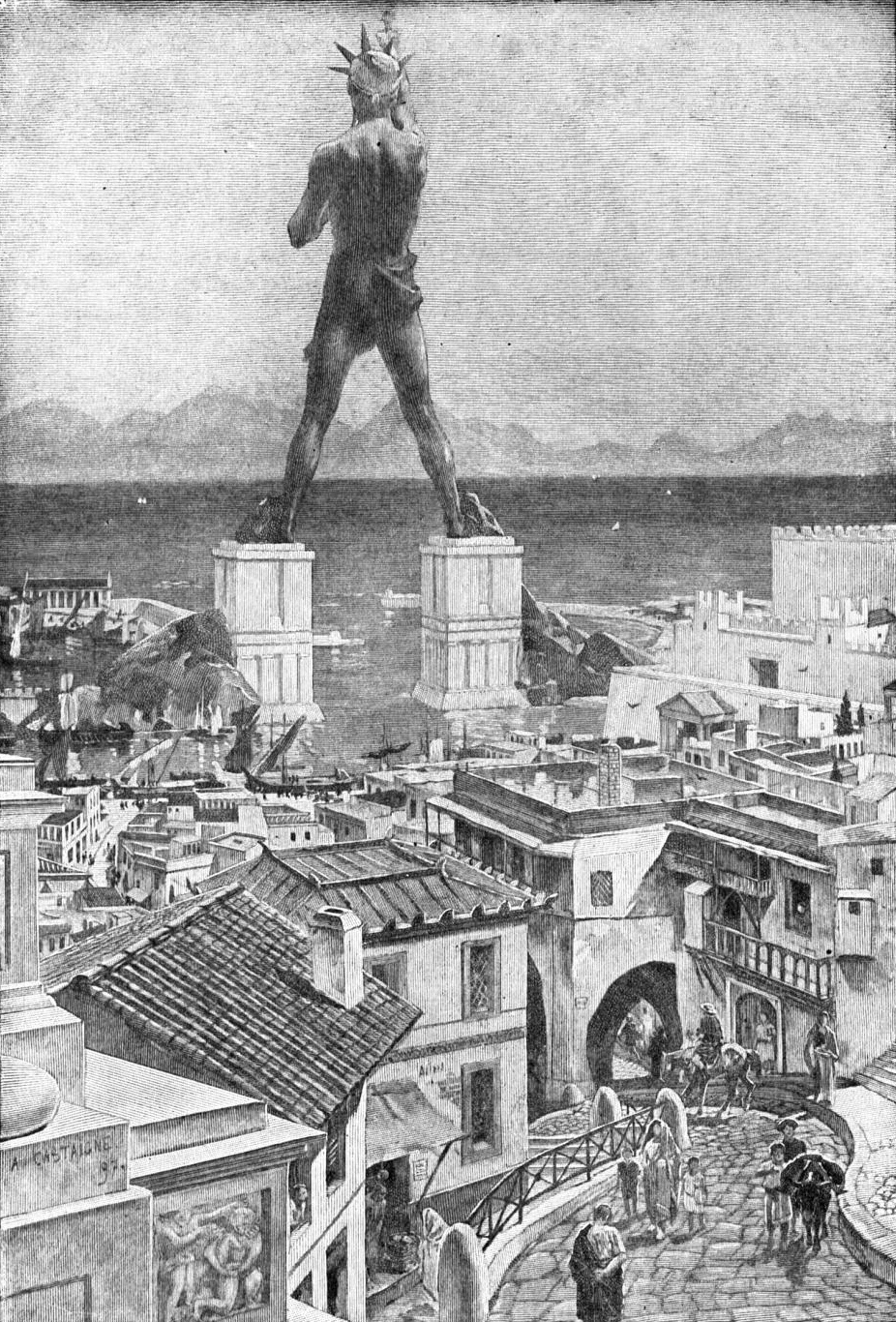

The harbor-straddling Colossus was a figment of medieval imaginations based on the dedication text's mention of "over land and sea" twice. Many older illustrations (above) show the statue with one foot on either side of the harbor mouth with ships passing under it: "...the brazen giant of Greek fame, with conquering limbs astride from land to land..." ("The New Colossus", a poem engraved on a bronze plaque and mounted inside the Statue of Liberty in 1903). Shakespeare's Cassius in Julius Caesar (I,ii,136–38) says of Caesar:

Why man, he doth bestride the narrow world

Like a Colossus, and we petty men

Walk under his huge legs and peep about

To find ourselves dishonorable graves

Shakespeare alludes to the Colossus also in Troilus and Cressida (V.5) and in Henry IV, Part 1 (V.1).

While these fanciful images feed the misconception, the mechanics of the situation reveal that the Colossus could not have straddled the harbor as described in Lemprière's Classical Dictionary. If the completed statue straddled the harbor, the entire mouth of the harbor would have been effectively closed during the entirety of the construction; nor would the ancient Rhodians have had the means to dredge and re-open the harbor after construction. The statue fell in 224 BC: if it straddled the harbor mouth, it would have entirely blocked the harbor. Also, since the ancients would not have had the ability to remove the entire statue from the harbor, it would not have remained visible on land for the next 800 years, as discussed above. Even neglecting these objections, the statue was made of bronze, and an engineering analysis proved[citation needed] that it could not have been built with its legs apart without collapsing from its own weight. Many researchers have considered alternate positions for the statue which would have made it more feasible for actual construction by the ancients.[citation needed] The design, posture and dimensions of the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor are based on what the Colossus was thought by engineers in the late 19th century to have looked like.

Location of the ruins

Media reports in 1989 initially suggested that large stones found on the seabed off the coast of Rhodes might have been the remains of the Colossus; however this theory was later shown to be without merit.

Another theory published in an article in 2008 by Ursula Vedder suggests that the Colossus was never in the port, but rather on a hill named Monte Smith, which overlooks the port area. The temple on top of Monte Smith has traditionally thought to have been devoted to Apollo, but according to Vedder, it would have been a Helios sanctuary. The enormous stone foundations at the temple site, the function of which is not definitively known by modern scholars, are proposed by Vedder to have been the supporting platform of the Colossus.[10]

Modern times

Americans will be aware of the reference to the Colossus in the poem "The New Colossus" by Emma Lazarus, written in 1883 and inscribed on a plaque located inside the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty, in New York Harbor:

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

"Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!" cries she

With silent lips. "Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!"

There has been much debate as to whether to rebuild the Colossus. Those in favor say it would boost tourism in Rhodes greatly, but those against construction say it would cost too large an amount (over 100 million euro). This idea has been revived many times since it was first proposed in 1970 but, due to lack of funding, work has not yet started.

Rebuilding

In November 2008, it was announced that the Colossus of Rhodes was to be rebuilt. According to Dr. Dimitris Koutoulas, who is heading the project in Greece, rather than reproducing the original Colossus, the new structure will be a, "highly, highly innovative light sculpture, one that will stand between 60 and 100 metres tall so that people can physically enter it." The project is expected to cost up to €200m which will be provided by international donors and the German artist Gert Hof. The new Colossus will adorn an outer pier in the harbour area of Rhodes, where it will be visible to passing ships. Koutoulas said, "Although we are still at the drawing board stage, Gert Hof's plan is to make it the world's largest light installation, a structure that has never before been seen in any place of the world."[11]

See also

References

- James R. Ashley (2004). Macedonian Empire. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-1918-0. page 75

Notes

- ^ The Colossus of Nero was either 100 or 120-foot (37 m) tall depending on the source. The Colossus of Rhodes was the same height as the Statue of Liberty (33 m). The pedestal it stood on is thought to have been smaller.

- ^ Pliny's Natural History xxxiv.18.

- ^ Forty cubits high, according to Pliny the Elder (Natural History xxxiv.18).

- ^ Accounts of Philo of Byzantium ca. 150 B.C. and Pliny (Plineus Caius Secundus) ca. 50 A.D. based on viewing the broken remains

- ^ Anthologia Graeca 4, 171 H. Beckby (Munich 1957)

- ^ International Symposium on History of Machines and Mechanisms: Engineering Aspects of the Collapse of the Colossus of Rhodes Statue. pages 69 - 85 ISBN 978-1-4020-2203-6

- ^ Natural History, book 34, xviii, 41.

- ^ See also Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos, De administrando imperio xx-xxi.

- ^ The Arabs and the Colossus. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 3rd ser. L.I. Conrad July 1996 Pg 165-187

- ^ P.M. HISTORY April 2008

- ^ Helena Smith, Colossus of Rhodes to be rebuilt as giant light sculpture, Guardian UK Online, 17 November 2008 (retrieved 19 November 2008).

External links

- Colossus

- Discover Rhodes

- Rhodes Guide

- Herbert Maryon, "The Colossus of Rhodes" The Journal of Hellenic Studies 76 (1956), pp. 68-86. A sculptor's speculations on the Colossus of Rhodes.

- D. E. L. Haynes, "Philo of Byzantium and the Colossus of Rhodes" The Journal of Hellenic Studies 77.2 (1957), pp. 311-312. A response to Maryon.

- M. H. Gabriel, BCH 16 (1932), pp 332-42.

|

|||||