Cuneiform script

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article contains special characters. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols. |

| Cuneiform | |

|

|

| Type | Logographic and syllabic |

|---|---|

| Spoken languages | Akkadian, Eblaite, Elamite, Hattic, Hittite, Hurrian, Luwian, Sumerian, Urartian |

| Time period | ca. 30th century BC to 1st century AD |

| Parent systems |

→ Cuneiform

|

| Child systems | Old Persian, Ugaritic |

| Unicode range | U+12000 to U+1236E (Sumero-Akkadian Cuneiform) U+12400 to U+12473 (Numbers) |

| ISO 15924 | Xsux |

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | |

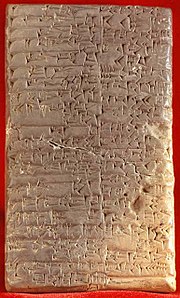

Cuneiform script (pronounced /kjuːˈniːɨfɔrm/ kew-NEE-i-form or KEWN-i-form) is one of the earliest known forms of written expression. Emerging in Sumer around the 30th century BC, with predecessors reaching into the late 4th millennium (the Uruk IV period), cuneiform writing began as a system of pictographs. In the course of the 3rd millennium BC the pictorial representations became simplified and more abstract. The number of characters in use also grew gradually smaller, from about 1,000 unique characters in the Early Bronze Age to about 400 unique characters in Late Bronze Age Hittite cuneiform. Cuneiform writing was gradually replaced by alphabetic writing in the Iron Age Neo-Assyrian Empire and was practically extinct by the beginning of the Common Era. It was deciphered from scratch in 19th century scholarship.

Cuneiform documents were written on clay tablets, by means of a blunt reed for a stylus. The impressions left by the stylus were wedge shaped, thus giving rise to the name cuneiform ("wedge shaped," from the Latin cuneus, meaning "wedge").

The Sumerian script was adapted for the writing of the Akkadian, Eblaite, Elamite, Hittite, Luwian, Hattic, Hurrian, and Urartian languages, and it inspired the Ugaritic and Old Persian national alphabets.

Contents |

[edit] History

The cuneiform writing system originated perhaps around 2900 BC[1] in Sumer; its latest surviving use is dated to 75 AD.[2]

The cuneiform script underwent considerable changes over a period of more than two millennia. The image below shows the development of the sign SAG "head" (Borger nr. 184, U+12295 𒊕).

Stage 1 shows the pictogram as it was drawn around 3000 BC. Stage 2 shows the rotated pictogram as written around 2800 BC. Stage 3 shows the abstracted glyph in archaic monumental inscriptions, from ca. 2600 BC, and stage 4 is the sign as written in clay, contemporary to stage 3. Stage 5 represents the late 3rd millennium, and stage 6 represents Old Assyrian ductus of the early 2nd millennium, as adopted into Hittite. Stage 7 is the simplified sign as written by Assyrian scribes in the early 1st millennium, and until the script's extinction.

[edit] Pictograms

Originally, pictograms were drawn on clay tablets in vertical columns with a pen made from a sharpened reed stylus, or incised in stone. This early style lacked the characteristic wedge-shape of the strokes.

Certain signs to indicate names of gods, countries, cities, vessels, birds, trees, etc., are known as determinants, and were the Sumerian signs of the terms in question, added as a guide for the reader. Proper names continued to be usually written in purely "ideographic" fashion.

The cuneiform script proper emerges out of pictographic proto-writing in the later 4th millennium. Mesopotamia's "proto-literate" period spans the 35th to 32nd centuries. The first documents unequivocally written in the Sumerian language date to the 31st century, found at Jemdet Nasr.

From about 2900 BC, many pictographs began to lose their original function, and a given sign could have various meanings depending on context. The sign inventory was reduced from some 1,500 signs to some 600 signs, and writing became increasingly phonological. Determinative signs were re-introduced to avoid ambiguity. This process is chronologically parallel to, and possibly not independent of[citation needed], the development of Egyptian hieroglyphic orthography.

[edit] Archaic cuneiform

In the mid-3rd millennium, writing direction was changed to left to right in horizontal rows (rotating all of the pictograms 90° counter-clockwise in the process), and a new wedge-tipped stylus was used which was pushed into the clay, producing wedge-shaped ("cuneiform") signs; these two developments made writing quicker and easier. By adjusting the relative position of the tablet to the stylus, the writer could use a single tool to make a variety of impressions.

Cuneiform tablets could be fired in kilns to provide a permanent record, or they could be recycled if permanence was not needed. Many of the clay tablets found by archaeologists were preserved because they were fired when attacking armies burned the building in which they were kept.

The script was also widely used on commemorative stelae and carved reliefs to record the achievements of the ruler in whose honour the monument had been erected.

[edit] Akkadian cuneiform

The archaic cuneiform script was adopted by the Akkadians from ca. 2500 BC, and by 2000 BC had evolved into Old Assyrian cuneiform, with many modifications to Sumerian orthography. The Semitic equivalents for many signs became distorted or abbreviated to form new "phonetic" values, because the syllabic nature of the script as refined by the Sumerians was unintuitive to Semitic speakers.

At this stage, the former pictograms were reduced to a high level of abstraction, and were composed of only five basic wedge shapes: horizontal, vertical, two diagonals and the Winkelhaken impressed vertically by the tip of the stylus. The signs exemplary of these basic wedges are

- AŠ (B001, U+12038) 𒀸: horizontal;

- DIŠ (B748, U+12079) 𒁹: vertical;

- GE23, DIŠ tenû (B575, U+12039) 𒀹: downward diagonal;

- GE22 (B647, U+1203A) 𒀺: upward diagonal;

- U (B661, U+1230B) 𒌋: the Winkelhaken.

Except for the Winkelhaken which is tail-less, the length of the wedges' tails could vary as required for sign composition.

Signs tilted by (ca.) 45 degrees are called tenû in Akkadian, thus DIŠ is a vertical wedge and DIŠ tenû a diagonal one. Signs modified with additional wedges are called gunû, and signs crosshatched with additional Winkelhaken are called šešig.

"Typical" signs have usually in the range of about five to ten wedges, while complex ligatures can consist of twenty or more (although it is not always clear if a ligature should be considered a single sign or two collated but still distinct signs); the ligature KAxGUR7 consists of 31 strokes.

Most later adaptations of Sumerian cuneiform preserved at least some aspects of the Sumerian script. Written Akkadian included phonetic symbols from the Sumerian syllabary, together with logograms that were read as whole words. Many signs in the script were polyvalent, having both a syllabic and logographic meaning. The complexity of the system bears a resemblance to old Japanese, written in a Chinese-derived script, where some of these Sinograms were used as logograms, and others as phonetic characters.

[edit] Assyrian cuneiform

This "mixed" method of writing continued through the end of the Babylonian and Assyrian empires, although there were periods when "purism" was in fashion and there was a more marked tendency to spell out the words laboriously, in preference to using signs with a phonetic complement. Yet even in those days, the Babylonian syllabary remained a mixture of ideographic and phonetic writing.

Hittite cuneiform is an adaptation of the Old Assyrian cuneiform of ca. 1800 BC to the Hittite language. When the cuneiform script was adapted to writing Hittite, a layer of Akkadian logographic spellings was added to the script, with the result that we no longer know the pronunciations of many Hittite words conventionally written by logograms.

In the Iron Age (ca. 10th to 6th c. BC), Assyrian cuneiform was further simplified. From the 6th century, the Assyrian language was marginalized by Aramaic, written in the Aramaean alphabet, but Neo-Assyrian cuneiform remained in use in literary tradition well into Parthian times ( 250 BC-226 AD ). The last known cuneiform inscription, an astronomical text, was written in 75 AD.[citation needed]

[edit] Derived scripts

The complexity of the system prompted the development of a number of simplified versions of the script. Old Persian was written in a subset of simplified cuneiform characters known today as Old Persian cuneiform. It formed a semi-alphabetic syllabary, using far fewer wedge strokes than Assyrian used, together with a handful of logograms for frequently occurring words like "god" and "king." The Ugaritic language was written using the Ugaritic alphabet, a standard Semitic style alphabet (an abjad) written using the cuneiform method.

[edit] Decipherment

Early European travellers to Persepolis (Iran) noticed carved cuneiform inscriptions and were intrigued. The Englishman Sir Thomas Herbert in the 1634 edition of his travel book “A relation of some yeares travaile” reported seeing at Persepolis carved on the wall “a dozen lines of strange characters…consisting of figures, obelisk, triangular, and pyramidal” and thought they resembled Greek. However by the 1664 edition he had guessed, correctly, that they represented not letters or hieroglyphics but words and syllables, and furthermore that they were to be read from left to right. He even reproduced some for his readers.[3] He was also correct in guessing that they were not merely decorative, but were ‘legible and intelligible’ and therefore decipherable. However, his insights never received the credit they perhaps deserved and he is never mentioned in standard histories of the decipherment of cuneiform.

Understanding of cuneiform therefore had to wait until Carsten Niebuhr brought the first reasonably complete and accurate copies of the inscriptions at Persepolis to Europe.[3] Bishop Frederic Munter of Copenhagen discovered that the words in the Persian inscriptions were divided from one another by an oblique wedge and that the monuments must belong to the age of Cyrus and his successors. One word, which occurs without any variation towards the beginning of each inscription, he correctly inferred to signify "king".[3] By 1802 Georg Friedrich Grotefend had determined that two king's names mentioned were Darius and Xerxes, and had been able to assign alphabetic values to the cuneiform characters which composed the two names.[4] [3]

In 1836, the eminent French scholar, Eugène Burnouf discovered that the first of the inscriptions published by Niebuhr contained a list of the satrapies of Darius. With this clue in his hand, he identified and published an alphabet of thirty letters, most of which he had correctly deciphered.[3][5][6]

A month earlier, Burnouf's friend and pupil, Professor Christian Lassen of Bonn, had also published a work on "The Old Persian Cuneiform Inscriptions of Persepolis".[7] [6] He and Burnouf had been in frequent correspondence, and his claim to have independently detected the names of the satrapies, and thereby to have fixed the values of the Persian characters, was in consequence fiercely attacked. According to Sayce, whatever his obligations to Burnouf may have been, Lassen's "contributions to the decipherment of the inscriptions were numerous and important. He succeeded in fixing the true values of nearly all the letters in the Persian alphabet, in translating the texts, and in proving that the language of them was not Zend, but stood to both Zend and Sanskrit in the relation of a sister."[3]

Meanwhile, in 1835 Henry Rawlinson, a British East India Company army officer, visited the Behistun inscriptions in Persia. Carved in the reign of King Darius of Persia (522 BC–486 BC), they consisted of identical texts in the three official languages of the empire: Old Persian, Babylonian, and Elamite. The Behistun inscription was to the decipherment of cuneiform what the Rosetta Stone was to the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Rawlinson correctly deduced that the Old Persian was a phonetic script and he successfully deciphered it. In 1837 he finished his copy of the Behistun inscription, and sent a translation of its opening paragraphs to the Royal Asiatic Society. Before, however, his Paper could be published, the works of Lassen and Burnouf reached him, necessitating a revision of his Paper and the postponement of its publication. Then came other causes of delay. In 1847 the first part of the Rawlinson's Memoir was published; the second part did not appear till 1849.[8] The task of deciphering the Persian cuneiform texts was virtually accomplished.[3]

After translating the Persian, Rawlinson and, working independently of him, the Anglo-Irish Egyptologist Edward Hincks, began to decipher the others. (The actual techniques used to decipher the Akkadian language have never been fully published; Hincks described how he sought the proper names already legible in the deciphered Persian while Rawlinson never said anything at all, leading some to speculate that he was secretly copying Hincks.[9]) They were greatly helped by Paul Émile Botta's discovery of the city of Nineveh in 1842. Among the treasures uncovered by Botta were the remains of the great library of Assurbanipal, a royal archive containing tens of thousands of baked clay tablets covered with cuneiform inscriptions.

By 1851, Hincks and Rawlinson could read 200 Babylonian signs. They were soon joined by two other decipherers: young German-born scholar Julius Oppert, and versatile British Orientalist William Henry Fox Talbot. In 1857 the four men met in London and took part in a famous experiment to test the accuracy of their decipherments. Edwin Norris, the secretary of the Royal Asiatic Society, gave each of them a copy of a recently discovered inscription from the reign of the Assyrian emperor Tiglath-Pileser I. A jury of experts was empanelled to examine the resulting translations and assess their accuracy. In all essential points the translations produced by the four scholars were found to be in close agreement with one another. There were of course some slight discrepancies. The inexperienced Talbot had made a number of mistakes, and Oppert's translation contained a few doubtful passages which the jury politely ascribed to his unfamiliarity with the English language. But Hincks' and Rawlinson's versions corresponded remarkably closely in many respects. The jury declared itself satisfied, and the decipherment of Akkadian cuneiform was adjudged a fait accompli.

In the early days of cuneiform decipherment, the reading of proper names presented the greatest difficulties. However, there is now a better understanding of the principles behind the formation and the pronunciation of the thousands of names found in historical records, business documents, votive inscriptions and literary productions. The primary challenge was posed by the characteristic use of old Sumerian non-phonetic ideograms in other languages that had different pronunciations for the same symbols. Until the exact phonetic reading of many names was determined through parallel passages or explanatory lists, scholars remained in doubt, or had recourse to conjectural or provisional readings. Fortunately, in many cases, there are variant readings, the same name being written phonetically (in whole or in part) in one instance, and ideographically in another.

[edit] Transliteration

Cuneiform has a specific format for transliteration. Because of the script's polyvalence, transliteration is not only lossless, but may actually contain more information than the original document. For example, the sign DINGIR in a Hittite text may represent either the Hittite syllable an or may be part of an Akkadian phrase, representing the syllable il, or it may be a Sumerogram, representing the original Sumerian meaning, 'god'. In transliteration, a different rendition of the same glyph is chosen depending on its role in the present context.

Therefore, a text containing DINGIR and MU in succession could be construed to represent the words "ana", "ila", god + "a" (the accusative ending), god + water, or a divine name "A" or Water. Someone transcribing the signs would make the decision how the signs should be read and assemble the signs as "ana", "ila", "Ila" ('god"+accusative case), etc. A transliteration of these signs, however, would separate the signs with dashes "il-a", "an-a", "DINGIR-a". This is still easier to read than the original cuneiform, but now the reader is able to trace the sounds back to the original signs and determine if the correct decision was made on how to read them.

There are differing conventions for transliterating Sumerian, Akkadian (Babylonian) and Hittite (and Luwian) cuneiform texts. One convention that sees wide use across the different fields is the use of acute and grave accents as an abbreviation for homophone disambiguation. Thus, u is equivalent to u1, the first glyph expressing phonetic u. An acute accent, ú, is equivalent to the second, u2, and a grave accent ù to the third, u3 glyph in the series (while the sequence of numbering is conventional but essentially arbitrary and subject to the history of decipherment). In Sumerian transliteration, a multiplication sign 'x' is used to indicate ligatures. As shown above, signs as such are represented in capital letters, while the specific reading selected in the transliteration is represented in small letters. Thus, capital letters can be used to indicate a so-called Diri compound - a sign sequence that has, in combination, a reading different from the sum of the individual constituent signs (for example, the compound IGI.A - "water" + "eye" - has the reading imhur, meaning "foam"). In a Diri compound, the individual signs are separated with dots in transliteration. Capital letters may also be used to indicate a Sumerogram (for example, KUG.BABBAR - Sumerian for "silver" - being used with the intended Akkadian reading kaspum, "silver"), an Akkadogram, or simply a sign sequence of whose reading the editor is uncertain. Naturally, the "real" reading, if it is clear, will be presented in small letters in the transliteration: IGI.A will be rendered as imhur4.

Since the Sumerian language has only been widely known and studied by scholars for approximately a century, changes in the accepted reading of Sumerian names have occurred from time to time. Thus the name of a king of Ur, read Ur-Bau at one time, was later read as Ur-Engur, and is now read as Ur-Nammu or Ur-Namma; for Lugal-zaggisi, a king of Uruk, some scholars continued to read Ungal-zaggisi; and so forth. Also, with some names of the older period, there was often uncertainty whether their bearers were Sumerians or Semites. If the former, then their names could be assumed to be read as Sumerian, while, if they were Semites, the signs for writing their names were probably to be read according to their Semitic equivalents, though occasionally Semites might be encountered bearing genuine Sumerian names. There was also doubt whether the signs composing a Semite's name represented a phonetic reading or an ideographic compound. Thus, e.g. when inscriptions of a Semitic ruler of Kish, whose name was written Uru-mu-ush, were first deciphered, that name was first taken to be ideographic because uru mu-ush could be read as "he founded a city" in Sumerian, and scholars accordingly "retranslated" it back to the "original" Semitic as Alu-usharshid. It was later recognized that the URU sign can also be read as rí and that the name is that of the Akkadian king Rimush.

[edit] Syllabary

The tables below show signs used for simple syllables of the form CV or VC. As used for the Sumerian language, the cuneiform script was in principle capable of distinguishing 14 consonants, transliterated as

- b, d, g, ḫ, k, l, m, n, p, r, s, š, t, z

as well as four vowel qualities, a, e, i, u. The Akkadian language needed to distinguish its emphatic series, q, ṣ, ṭ, adopting various "superfluous" Sumerian signs for the purpose (e.g. qe=KIN, qu=KUM, qi=KIN, ṣa=ZA, ṣe=ZÍ, ṭur=DUR etc.) Hittite as it adopted the Akkadian cuneiform further introduced signs for the glide w, e.g. wa=we=PIN, wi5=GEŠTIN) as well as a ligature I.A for ya.

| -a | -e | -i | -u | |

| a 𒀀, á 𒀉 |

e 𒂊, é 𒂍 |

i 𒄿, í=IÁ 𒐊 |

u 𒌋, ú 𒌑 |

|

| b- | ba 𒁀, bá=PA 𒉺, |

be=BAD 𒁁, bé=BI 𒁉, |

bi 𒁉, bí=NE 𒉈, |

bu 𒁍, bú=KASKAL 𒆜, |

| d- | da 𒁕, dá=TA 𒋫 |

de=DI 𒁲, dé , |

di 𒁲, dí=TÍ 𒄭 |

du 𒁺, dú=TU 𒌅, |

| g- | ga 𒂵, gá 𒂷 |

ge=GI 𒄀, gé=KID 𒆤, |

gi 𒄀, gí=KID 𒆤, |

gu 𒄖, gú 𒄘, |

| ḫ- | ḫa 𒄩, ḫá=ḪI.A 𒄭𒀀, |

ḫe=ḪI 𒄭, ḫé=GAN 𒃶 |

ḫi 𒄭, ḫí=GAN 𒃶 |

ḫu 𒄷 |

| k- | ka 𒅗, ká 𒆍, |

ke=KI 𒆠, ké=GI 𒄀 |

ki 𒆠, kí=GI 𒄀 |

ku 𒆪, kú=GU7 𒅥, |

| l- | la 𒆷, lá=LAL 𒇲, |

le=LI 𒇷, lé=NI 𒉌 |

li 𒇷, lí=NI 𒉌 |

lu 𒇻, lú 𒇽 |

| m- | ma 𒈠, má 𒈣 |

me 𒈨, mé=MI 𒈪, |

mi 𒈪, mí=MUNUS 𒊩, |

mu 𒈬, mú=SAR 𒊬 |

| n- | na 𒈾, ná 𒈿, |

ne 𒉈, né=NI 𒉌 |

ni 𒉌, ní=IM 𒉎 |

nu 𒉡, nú=NÁ 𒈿 |

| p- | pa 𒉺, pá=BA 𒐀 |

pe=PI 𒉿, pé=BI 𒁉 |

pi 𒉿, pí=BI 𒁉, |

pu=BU 𒁍, pú=TÚL 𒇥, |

| r- | ra 𒊏, rá=DU 𒁺 |

re=RI 𒊑, ré=URU 𒌷 |

ri 𒊑, rí=URU 𒌷 |

ru 𒊒, rú=GAG 𒆕, |

| s- | sa 𒊓, sá=DI 𒁲, |

se=SI 𒋛, sé=ZI 𒍣 |

si 𒋛, sí=ZI 𒍣 |

su 𒋢, sú=ZU 𒍪, |

| š- | ša 𒊭, šá=NÍG 𒐼, |

še 𒊺, šé , |

ši=IGI 𒅆, ší=SI 𒋛 |

šu 𒋗, šú 𒋙, |

| t- | ta 𒋫, tá=DA 𒁕 |

te 𒋼, té=TÍ 𒊹 |

ti 𒋾, tí 𒊹, |

tu 𒌅, tú=UD 𒌓, |

| z- | za 𒍝, zá=NA4 𒉌𒌓 |

ze=ZI 𒍣, zé=ZÌ 𒍢 |

zi 𒍣, zí 𒍢, |

zu 𒍪, zú=KA 𒅗 |

| a- | e- | i- | u- | |

| a 𒀀, á 𒀉 |

e 𒂊, é 𒂍 |

i 𒄿, í=IÁ 𒐊 |

u 𒌋, ú 𒌑 |

|

| -b | ab 𒀊, áb 𒀖 |

eb=IB 𒅁, éb=TUM 𒌈 |

ib 𒅁, íb=TUM 𒌈 |

ub 𒌒, úb=ŠÈ 𒂠 |

| -d | ad 𒀜, ád 𒄉 |

ed=Á 𒀉 | id=Á 𒀉, íd=A.ENGUR 𒀀𒇉 |

ud 𒌓, úd=ÁŠ 𒀾 |

| -g | ag 𒀝, ág 𒉘 |

eg=IG 𒅅, ég=E 𒂊 |

ig 𒅅, íg=E 𒂊 |

ug 𒊌 |

| -ḫ | aḫ 𒄴, áḫ=ŠEŠ 𒋀 |

eḫ=AḪ 𒄴 | iḫ=AḪ 𒄴 | uḫ=AḪ 𒄴, úḫ 𒌔 |

| -k | ak=AG 𒀝 | ek=IG 𒅅 | ik=IG 𒅅 | uk=UG 𒊌 |

| -l | al 𒀠, ál=ALAM 𒀩 |

el 𒂖, él=IL 𒅋 |

il 𒅋, íl 𒅍 |

ul úl=NU 𒉡 |

| -m | am 𒄠/𒂔, ám=ÁG 𒉘 |

em=IM 𒅎 | im 𒅎, ím=KAŠ4 𒁽 |

um 𒌝, úm=UD 𒌓 |

| -n | an 𒀭 | en 𒂗, én, |

in 𒅔, in4=EN 𒂗, |

un 𒌦, ún=U 𒌋 |

| -p | ap=AB 𒀊 | ep=IB , ép=TUM 𒌈 |

ip=IB 𒅁, íp=TUM 𒌈 |

up=UB 𒌒, úp=ŠÈ 𒂠 |

| -r | ar 𒅈, ár=UB 𒌒 |

er=IR 𒅕 | ir 𒅕, íp=A.IGI 𒀀𒅆 |

ur 𒌨, úr 𒌫 |

| -s | as=AZ 𒊍 | es=GIŠ 𒄑, és=EŠ 𒂠 |

is=GIŠ 𒄑, ís=EŠ 𒂠 |

us=UZ, ús=UŠ 𒍑 |

| -š | aš 𒀸, áš 𒀾 |

eš 𒌍/𒐁, éš=ŠÈ 𒂠 |

iš 𒅖, íš=KASKAL 𒆜 |

uš 𒍑, úš𒍗=BAD 𒁁 |

| -t | at=AD 𒀜, át=GÍR gunû 𒄉 |

et=Á 𒀉 | it=Á 𒀉 | ut=UD 𒌓, út=ÁŠ 𒀾 |

| -z | az 𒊍 | ez=GIŠ 𒄑, éz=EŠ 𒂠 |

iz= GIŠ 𒄑, íz=IŠ 𒅖 |

uz úz=UŠ 𒍑, |

[edit] Sign inventories

The Sumerian cuneiform script had of the order of 1,000 unique signs (or about 1,500 if variants are included). This number was reduced to about 600 by the 24th century BC and the beginning of Akkadian records. Not all Sumerian signs are used in Akkadian, and not all Akkadian signs are used in Hittite.

- Falkenstein (1936) lists 939 signs used in the earliest period (late Uruk, 34th to 31st centuries)

- Borger (2003) lists 907 signs.

- Deimel (1922) lists 870 signs used in the Early Dynastic IIIa period (26th century).

- Borger in 1981 lists 598 signs used in Assyrian/Babylonian writing, and 907 in 2003. His numbering is based on Deimel's Sumerisches Lexikon.

- Rosengarten (1967) lists 468 signs used in Sumerian (pre-Sargonian) Lagash.

- Signs used in Hittite cuneiform are listed by Forrer (1922), Friedrich (1960) and the HZL (Rüster and Neu 1989). The HZL lists a total of 375 signs, many with variants (for example, 12 variants are given for number 123 EGIR)

[edit] Unicode

Unicode (as of version 5.0) assigns to the Cuneiform script the following ranges:

- U+12000–U+1236E (879 characters) "Sumero-Akkadian Cuneiform"

- U+12400–U+12473 (103 characters) "Cuneiform Numbers"

The final proposal for Unicode encoding of the script was submitted by two cuneiform scholars working with an experienced Unicode proposal writer in June 2004.[1] The base character inventory is derived from the list of Ur III signs compiled by the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative of UCLA based on the inventories of Miguel Civil, Rykle Borger (2003), and Robert Englund. Rather than opting for a direct ordering by glyph shape and complexity, according to the numbering of an existing catalogue, the Unicode order of glyphs was based on the Latin alphabetic order of their 'main' Sumerian transliteration as a practical approximation.

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- R. Borger, Assyrisch-Babylonische Zeichenliste, 2nd ed., Neukirchen-Vluyn (1981)

- R. Borger, Mesopotamisches Zeichenlexikon, Münster (2003). [2]

- A. Deimel, Liste der archaischen Keilschriftzeichen (WVDOG 40; Berlin 1922) [3]

- F. Ellermeier, M. Studt, Sumerisches Glossar

- vol. 1: 1979-1980, ISBN 3-921747-08-2, ISBN 3-921747-10-4

- vol. 3.2: 1998-2005, A-B ISBN 3-921747-24-4, D-E ISBN 3-921747-25-2, G ISBN 3-921747-29-5

- vol. 3.3: ISBN 3-921747-22-8 (font CD ISBN 3-921747-23-6)

- vol. 3.5: ISBN 3-921747-26-0

- vol 3.6: 2003, Handbuch Assur ISBN 3-921747-28-7

- A. Falkenstein, Archaische Texte aus Uruk, Berlin-Leipzig (1936) [4]

- E. Forrer, Die Keilschrift von Boghazköi, Leipzig (1922)

- J. Friedrich, Hethitisches Keilschrift-Lesebuch, Heidelberg (1960)

- Jean-Jacques Glassner, The Invention of Cuneiform, English translation, Johns Hopkins University Press (2003), ISBN 0-8018-7389-4.

- René Labat, Manuel d'epigraphie Akkadienne, Geuthner, Paris (1959); 6th ed., extended by Florence Malbran-Labat (1999), ISBN 2-7053-3583-8.

- O. Neugebauer, A. Sachs (eds.), Mathematical Cuneiform Texts, New Haven (1945).

- Y. Rosengarten, Répertoire commenté des signes présargoniques sumériens de Lagash, Paris (1967) [5]

- Chr. Rüster, E. Neu, Hethitisches Zeichenlexikon (HZL), Wiesbaden (1989)

- Nikolaus Schneider, Die Keilschriftzeichen der Wirtschaftsurkunden von Ur III nebst ihren charakteristischsten Schreibvarianten, Keilschrift-Paläographie; Heft 2, Rom: Päpstliches Bibelinstitut (1935). [6]

- Wolfgang Schramm, Akkadische Logogramme, Goettinger Arbeitshefte zur Altorientalischen Literatur (GAAL) Heft 4, Goettingen (2003), ISBN 3-936297-01-0.

- F. Thureau-Dangin, Recherches sur l'origine de l'écriture cunéiforme, Paris (1898).

- Ronald Herbert Sack, Cuneiform Documents from the Chaldean and Persian Periods, (1994) ISBN 0945636679

[edit] Notes

- ^ The Origin and Development of the Cuneiform System of Writing, Samuel Noah Kramer, Thirty Nine Firsts In Recorded History, pp 381-383

- ^ Adkins, Lesley (2003). Empires of the Plain. HarperCollins. pp. 47. ISBN 0 00 712899 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sayce, Rev. A. H., Professor of Assyriology, Oxford, "The Archaeology of the Cuneiform Inscriptions", Second Edition-revised, 1908, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London, Brighton, New York; at pp 9-16 Not in copyright

- ^ Heeren: "Ideen iiber die Politik, den Verkehr und den Handel der vornehmsten Volker der alien Welt", vol. i. pp. 563 seq., 1815, translated into English in 1833. Although Grotefend's Memoir was presented to the Gottingen Academy on September 4, 1802, the Academy refused to publish it; it was subsequently published in this work in 1815.

- ^ Burnouf, E. "Memoire sur deux Inscriptions Cuneiformes trouvees pres d'Hamadan et qui font partie des papiers du Dr Schulz", 1836, Impr. Roy, Paris.

- ^ a b Prichard, James Cowles, "Researches Into the Physical History of Mankind", 3rd Ed., Vol IV, 1844, Sherwood, Gilbert and Piper, London, at pages 30-31

- ^ Lassen, Christian, "Die Altpersischen Keil-Inschriften von Persepolis"

- ^ Rawlinson Henry 1847 "The Persian Cuneiform Inscription at Behistun, decyphered and translated; with a Memoir on Persian Cuneiform Inscriptions in general, and on that of Behistun in Particular", The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol X. It seems that various parts of this paper formed Vol X of this journal. The final part III comprised of chapters IV (Analysis of the Persian Inscriptions of Behistunand) and V (Copies and Translations of the Persian Cuneiform Inscriptions of Persepolis, Hamadan, and Van), pp. 187-349.

- ^ Daniels, Peter; Bright, William (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. pp. 146. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Cuneiform |

- Akkadian (specifically, Neo-Assyrian) sign list (alain.be) - In French

- Analysis and reports to support an international standard for computer encoding of the Cuneiform writing system

- Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative. A Joint Project of the University of California at Los Angeles and the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science.

- Cuneiform Texts from Babylonian Tablets, &c. in the British Museum, Budge, E.A., London, Harrison and Sons, 1896.

- ETCSL (Sumerian) sign list

- Evolution of Cuneiform

- Neo-Assyrian sign list

- Digital encoding and rendering

- Online interactive cuneiform tablet from the State Library of Victoria collection.

- Online Translator - Translates English words, sentences, and phrases into ancient Assyrian, Babylonian, Sumerian cuneiform

- Fonts

- Unicode

- Akkadian (reproduces the archaic (Ur III) glyphs given in the Unicode reference chart, themselves based on a font by Steve Tinney)

- Cuneiform Composite (free Cuneiform font), also Ur III. Designed by Steve Tinney with input from Michael Everson.

- FreeIdgSerif (branched off FreeSerif), encodes some 390 Old Assyrian glyphs used in Hittite cuneiform.

- non-Unicode

- Cuneiform fonts for TeX/LaTeX/PDFLaTeX by Karel Piska (Type 1, GPL)

- Sumerian font by Carsten Peust (TrueType, freeware)

- Ullikummi (Hittite package) by Sylvie Vanséveren (TrueType, freeware)

- UR III font by Guillaume Malingue (TrueType, freeware)

|

|||||||||||