California English

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. Please improve this article if you can. (January 2009) |

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2009) |

California English is a dialect of the English language spoken in the U.S. state of California. The most populous state of the United States, California is home to a highly diverse populace, which is reflected in the historical and continuing development of California English. As is the case of English spoken in any particular state, not all features are used by all speakers in the state, and not all features are restricted in use only to the state. However, there are some linguistic features which can be identified as either originally or predominantly Californian, or both.

Contents |

[edit] History

English became spoken in the area now known as California on a wide scale beginning with a considerable influx of English-speaking European Americans during the California Gold Rush and after rapid growth from internal migration (from all parts of the United States, but particularly New England in earlier periods and later on, the Midwest) through the end of the 19th century and first half of the 20th century. The heavy internal migration from regions in the United States east of California laid the early groundwork for the varieties of English spoken in California today.

Before World War I, the variety of speech types reflected the differing origins of these early inhabitants. At the time a distinctly southwestern drawl could be heard in Southern California, although the San Francisco area sounded more Midwestern.[citation needed] When a collapse in commodity prices followed World War I, many bankrupted Midwestern farmers migrated to California, bringing speech characteristic of Nebraska, Ohio, Illinois, Minnesota, and Iowa; and this speech type has dominated to this day. Subsequently, incoming groups with differing speech, such as the speakers of Highland Southern during the 1930s, have been absorbed within a generation.

California's status as a relatively young state is significant in that it has not had centuries for regional patterns to emerge and grow (compared to, say, some East Coast or Southern dialects). Linguists who studied English as spoken in California before and in the period immediately after World War II tended to find few if any distinct patterns unique to the region[1]. However, several decades later, with a more settled population and continued immigration from all over the globe, a noteworthy set of emerging characteristics of California English had begun to attract notice by linguists of the late 20th century and on.

[edit] Phonology

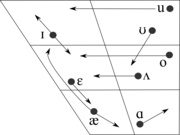

As a variety of American English, California English is similar to most other forms of American speech in being a rhotic accent, which is historically a significant marker in differentiating different English varieties. The following chart represents the relative positions of the stressed monophthongs of the accent, based on nine speakers from southern California.[2] Notable is the absence of /ɔ/, which has merged with /ɑ/ through the cot-caught merger, and the relatively open quality of /ɪ/ due to the California vowel shift discussed below.

Several phonological processes have been identified as being particular to California English. However, these shifts are by no means universal in Californian speech, and any single Californian's speech may only have some or none of the changes identified below. The shifts might also be found in the speech of people from areas outside of California.

- Front vowels are raised before velar nasal /ŋ/, so that the near-open front unrounded vowel /æ/ and the near-close near-front unrounded vowel /ɪ/ are raised to a close-mid front unrounded vowel [e] and a close front unrounded vowel [i] before /ŋ/. This change makes for minimal pairs such as king and keen, both having the same vowel [i], differing from king [kɪŋ] in other varieties of English. Similarly, a word like rang will often have the same vowel as rain in California English, not the same vowel as ran as in other varieties.

- The vowels in words such as Mary, marry, merry are merged to the open-mid front unrounded vowel [ɛ]

- Most speakers do not distinguish between the open-mid back rounded vowel /ɔ/ and open back unrounded vowel /ɑ/, characteristic of the cot-caught merger. A notable exception may be found within the San Francisco Bay Area, whose native inhabitants' speech somewhat reflects a historical East-Coast heritage which has probably influenced the maintenance of the distinction between words such as caught and cot.

- According to phoneticians studying California English, such as Penelope Eckert, traditionally diphthongal vowels such as /oʊ/ as in boat and /eɪ/, as in bait, have acquired qualities much closer to monophthongs in some speakers.

- The pin-pen merger is complete in Bakersfield, and speakers in Sacramento either perceive or produce the pairs /ɛn/ and /ɪn/ close to each other[3].

One topic that has begun to receive much attention among scholars in recent years has been the emergence of a vowel shift unique to California. Much like other vowel shifts occurring in North America, such as the Southern Shift, Northern Cities Shift, and the Canadian Shift, the California Vowel Shift is noted for a systematic chain shift of several vowels.

This image on the right illustrates the California vowel shift. The vowel space of the image is a cross-section (as if looking at the interior of a mouth from a side profile perspective); it is a rough approximation of the space in a human mouth where the tongue is located in articulating certain vowel sounds (the left is the front of the mouth closer to the teeth, the right side of the chart being the back of the mouth). As with other vowel shifts, several vowels may be seen moving in a chain shift around the mouth. As one vowel encroaches upon the space of another, the adjacent vowel in turn experiences a movement in order to maximize phonemic differentiation.

Two phonemes, /ɪ/ and /æ/, have allophones that are fairly widely spread apart from each other: before /ŋ/, /ɪ/ is raised to [i] and, as mentioned above, may even be identified with the phoneme /i/. In other contexts, /ɪ/ has a fairly open pronunciation, as indicated in the vowel chart above. /æ/ is raised and diphthongized to [eə] or [ɪə] before nasal consonants (a shift reminiscent of, but more restricted than, non-phonemic æ-tensing in the Inland North); before /ŋ/ it may be identified with the phoneme /e/. Elsewhere /æ/ is lowered in the direction of [a]. The other parts of the chain shift are apparently context-free: /ʊ/ is moving towards [ʌ], /ʌ/ towards [ɛ], /ɛ/ toward [æ], /ɑ/ toward [ɔ], and /u/ and /oʊ/ are diphthongs whose nuclei are moving toward [i] and [e] respectively.

Unlike some of the other vowel shifts, however, the California Shift is generally considered to be in earlier stages of development as compared to the more widespread Northern Cities and Southern Shifts, although the new vowel characteristics of the California Shift are increasingly found among younger speakers. As with many vowel shifts, these significant changes occurring in the spoken language are rarely noticed by average speakers; imitation of peers and other sociolinguistic phenomena play a large part in determining the extent of the vowel shift in a particular speaker. For example, while some characteristics such as the close central rounded vowel [ʉ] or close back unrounded vowel [ɯ] for /u/ are widespread in Californian speech, the same high degree of fronting for /oʊ/ is common only within certain social groups.

Older native Californians tend to pronounce the suffixes -ive (motive) and -age (message) as eve and eej, respectively.[citation needed]

[edit] Lexical characteristics

The popular image of a typical California speaker often conjures up images of the so-called Valley Girls popularized by the 1982 hit song by Frank Zappa and Moon Unit Zappa or "surfer-dude" speech made famous by movies such as Fast Times at Ridgemont High. While many phrases found in these extreme versions of California English of the 1980s may now be considered passé, certain words such as awesome, totally, fer sure, harsh and dude have remained popular in California and have spread to a national, even international, level. The use of the word like for numerous grammatical functions or as conversational "filler" has also remained popular in California English and is now found in many other varieties of English.

A common example of a Northern California[citation needed] colloquialism is "hella" (from "hell of a (lot of)", alternatively, "hecka") to mean "many," "much," or "very".[4] It can be used with both count and mass nouns. For example: "I haven't seen you for hella long"; "There were hella people there"; or "This guacamole is hella good." Pop culture references to "hella" are common, as in the song "Hella Good" by the band No Doubt, which hails from Southern California.

California, like other Southwestern states, has borrowed many words from Spanish, especially for place names, food, and other cultural items, reflecting the heritage of Mexican Californians. High concentrations of various ethnic groups throughout the state have contributed to general familiarity with words describing (especially cultural) phenomena. For example, a high concentration of Asian Americans from various cultural backgrounds, especially in urban and suburban metropolitan areas in California, has led to the adoption of words like hapa (itself originally a Hawaiian borrowing of English "half"[5]). A person who was hapa was either part European/Islander or part Asian/Islander. Today it refers to a person of mixed racial heritage—especially, but not limited to, half-Asian/half-European-Americans in common California usage) and FOB ("fresh off the boat", often a newly arrived Asian immigrant). Not surprisingly, the popularity of cultural food items such as Vietnamese phở and Taiwanese boba in many areas has led to the general adoption of such words amongst many speakers.

[edit] Freeway nomenclature

| This section may contain original research or unverified claims. Please improve the article by adding references. See the talk page for details. (September 2007) |

Since the 1950s and 1960s, California culture (and thus its variety of English) has been significantly affected by "car culture" – that is, dependence on private automobile transportation and the effects thereof.

One difference between California and most of the rest of the U.S. has been the way residents refer to highways, or freeways. The term freeway itself is not used in many areas outside California; for instance, in New England, the term highway is universally used. Where most Americans may refer to "I-80" for the east-west Interstate Highway leading from San Francisco to the suburbs of New York, or "I-15" for the north-south artery linking San Diego through Salt Lake City to the Canadian border, Californians are less likely to use the "I" or "interstate" designation in naming highways or freeways.

- Northern California

- Northern Californians will typically say "80", "101 (one oh one)" to refer to freeways. Some long-time San Francisco Bay Area residents and many traffic report broadcasts still refer to such highways by name and not number designation: "the Bayshore" for 101, or "the Nimitz" for I-880, which was named for Admiral Chester Nimitz, a prominent World War II hero with strong local ties. State Route 1 is called "Highway 1" or simply "One" (i.e., "take One down the coast").

- Southern California

- In Greater Los Angeles, Orange County and San Diego, Interstate Highways are referred to either by name or by route number (perhaps with a direction suffix), but with the addition of the article "the", such as "the 405 North" or "the 605". This is in contrast to typical Northern California usage, which omits the article.

There is no road named "Los Angeles Freeway"; instead, each freeway which radiates from downtown L.A. is named for its nominal terminus in some other city, such as Santa Monica, Santa Ana, or San Diego. News reports will occasionally refer to the Santa Monica and Santa Ana freeways as such; however, residents will very rarely refer to the 405 freeway as the San Diego Freeway (other than on street signs). The majority of natives stick to calling the freeways by their numerical name.[citation needed]

Conversely, the older state highways are generally called not by their numbers, but by their names, as used on signage and in postal addresses. For example, in southern California, State Route 1, is called Pacific Coast Highway, and is often referred to as "PCH", pronounced as three separate letters.

The numbering of freeway exits, common in most parts of the United States, has only recently been applied in California and initially appearing only in more populous areas. Thus, virtually all Californians refer to exits by signage name rather than by number, as in "Grand Avenue exit" rather than "Exit 21."

Southern Californians often refer to the lanes of a multi-lane divided highway by number, "The Number 1 Lane" (usually referred to as "The Fast Lane") is the lane furthest to the left, with the lane numbers going up sequentially to the right until the far right lane, which is usually referred to as "The Slow Lane."

[edit] Place names

[edit] Northern California

Another common Northern California expression is the way in which residents refer to San Francisco as simply "The City" if they live in nearby suburbs (such as San Mateo) or cities like Oakland or Danville, or even as far south as Santa Cruz. Some Mexican Spanish-speakers refer to it as "San Pancho" because Pancho is a nickname for the Spanish name Francisco[citation needed]. Similarly, the city of South San Francisco, technically not a part of the city and county of San Francisco, is sometimes referred to as "South City", especially in the pages of the San Francisco Examiner. The term "Frisco" is almost never used by residents, except in jest, much as "The Big Apple" is not typically used by native New Yorkers. However, although well-known newspaper columnist Herb Caen once harshly criticized the use of the term "Frisco", he later recanted, and the term continues to be used. Still, the term "Frisco" continues to be viewed by many northern Californians as either revealing ignorance, or as vaguely derogatory. When used by northern Californians, it is typically employed with a sense of irony.

| “ | Whoever after due and proper warning shall be heard to utter the abominable word "Frisco", which has no linguistic or other warrant, shall be deemed guilty of a High Misdemeanor, and shall pay into the Imperial Treasury as penalty the sum of twenty-five dollars.[6] | ” |

|

—Emperor Norton, nineteenth-century San Francisco figure |

||

Northern California and Southern California are sometimes abbreviated as "NorCal" and "SoCal", respectively. Some Southern Californians refer to Northern California as "NoCal" to emphasize perceived feelings of Southern California's superiority. Similarly, "SoCal" is often used derisively in some areas of Northern California, ("Oh, he's from SoCal, no wonder he's such an airhead."), especially in conversations about water usage or Los Angeles (sometimes referred to as "La La Land").

The metro region often referred to as the Bay Area includes San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Alameda, Marin, Contra Costa, Sonoma, Solano and Napa counties.

The San Francisco Bay Area is occasionally referred to as "the Bay" and more commonly "The Bay Area". The San Francisco Bay Area is sub-divided into regions such as:

- The "North Bay" (Marin County, the southern half of Napa County and the southern half of Sonoma County with the northern border of the North Bay ending just north of Santa Rosa). The northern portions of Sonoma and Napa counties are typically considered to be Wine Country, a separate region. Some cities in central areas of these counties are considered to be members of both communities.

- The "South Bay" (Santa Clara County—San Jose, Milpitas, and surrounding cities, sometimes extending as far south as Gilroy)

- The "East Bay" (Alameda and Contra Costa counties—Oakland, Berkeley, Walnut Creek, Fremont, Hayward, Martinez, Pittsburg, etc.)

- "The Peninsula" (San Mateo county, including San Mateo, Redwood City, Menlo Park, et cetera, but excluding San Francisco).

- "The City" (San Francisco).

A few Northern Californians refer to Sacramento, the state capital, as "Sac", "Sacto", "Sactown", "Sacra" (by the Chicano community), and various other nicknames.

Residents of the San Fernando Valley (the section of Los Angeles to the north of the Santa Monica mountains) often use the phrase "over the hill" to refer to Los Angeles, where the San Fernando Valley itself is generally called "the Valley". Similarly, Bay Area and Sacramento residents speak of going "up the hill" into the neighboring mountains to Lake Tahoe or Reno, Nevada, but "over the hill" for crossing the Santa Cruz Mountains. In the Sacramento area, "the Valley" refers to the Central Valley. Additionally, residents of the San Francisco Bay Area will sometimes refer to the area of the Santa Clara Valley and surrounding cities as "the Valley" and sometimes as the more famous term, "Silicon Valley". Residents of Santa Cruz use the phrase "over the hill" to refer to Silicon Valley, but for them "the Bay" refers to closer Monterey Bay, not San Francisco Bay.

[edit] Southern California

Southern Californians have a noticeable tendency to add the definite article when referring to placenames (i.e. "The Grapevine," "The Southland"), especially highway numbers and names (e.g. "The 101" rather than just "101", and "The Artesia Freeway" instead of just "Artesia Freeway"). Conversely, the typical San Francisco usage of the article with streets or intersections to denote districts and, by extension, their lifestyles and cultures is not found in Los Angeles, unless suffixed with a geographical term; one might hear "the Pico Union" district, but not The Pico Union.

Southern California has many distinctive accents and dialects; these often reflect the geographic origins of the people who came there. Bakersfield English and the "Valley Girl" dialect of the San Fernando Valley have their roots in the Ozark English of Arkansas and Missouri, and first developed when many people from the Ozarks migrated to California in the 1930s. East Los Angeles and the Gateway Cities house a distinctive form of Chicano English, notable for its use of the word "foo" for any person. These dialects can exist in very small areas, such as the traditionally New Orleanian Yat in northern Pasadena.

In Los Angeles County, the "South Bay" refers to the area between Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) and Los Angeles Harbor. This area is usually downwind from the southern part of Santa Monica Bay and includes the cities of Hawthorne, Torrance, El Segundo, Manhattan Beach, Redondo Beach and Gardena as well as several others.

In San Diego County, South Bay refers to the area adjacent to the southern portion of San Diego Bay. Suburbs in the northern half of the county near-universally identify as simply North County, and suburbs immediately east of the city proper, though geographically still located in the western half of the county, identify similarly as East County. It is also common to refer to the many beach communities by their initials, e.g. IB, OB, and PB, for Imperial Beach, Ocean Beach, and Pacific Beach respectively.

In Los Angeles, "Eastside" and "Westside" relate to their position to Downtown Los Angeles. The Westside, which includes areas like Beverly Hills and Crescent Heights, is often perceived to be more affluent. The border between the Westside and Downtown Los Angeles is fluid, with some defining the border as the 110 Freeway, Western Avenue, or another location. The Eastside's border with Downtown Los Angeles is the Los Angeles River. Everything east of the Los Angeles River is the Eastside.

The area south of downtown Los Angeles, including Watts, was called "South Central", after Central Avenue, which runs through it and was a major location for jazz and nightlife in the fifties and sixties. Today it is usually called South LA, perhaps because the previous term became associated with gang violence. Also, the Inland Empire is commonly referred to as The I.E. or simply I.E.

A common complaint from residents of Southern California's Orange County is the reference to the area as "the OC" instead of just as "Orange County".[citation needed] Attributed to the Fox television show The O.C., the inclusion of the article in the county's name is mainly perceived to be used by those from outside of the area, rather than natives. In fact, use of the term around Orange County natives will often elicit a disgusted or annoyed response. This was parodied in the Fox TV series Arrested Development, which takes place in Orange County, in which when someone would refer to the county they would call it "the O.C.", prompting someone to respond "Don't call it that."

[edit] California sociolects and Chicano English

As it is a very diverse state (there is no ethnic majority in California), several significant sociolects associated with particular cultural or ethnic groups are found within California. Current and historical Mexican immigration to California has resulted in a unique form of English spoken by Chicanos in the state, with Chicano English receiving the most attention in linguistic research into sociolects in California English. Chicano English is a native variety of English marked by a historical and current Spanish substratum (whether or not the speakers in question speak Spanish). Researchers have paid particular attention to the use of "barely," representing "had just recently" which may or may not be in analogy with Spanish apenas[1]. Recently, research has shown California speakers of Chicano English have been participating in some aspects of the California Vowel Shift typically found in the speech of younger whites, Hispanics, and Asian Americans (amongst other groups), but some of the characteristics of the shift are altered for speakers of Chicano English.[1] Some hold that some Chicano English influences may be found in the speech of non-Chicano English speakers in California, such as the /ɪŋ/ → /in/ process mentioned above[1], but such will probably not be settled without further research into the area. It should also be noted that Chicano English is by no means spoken by all Chicanos in California and the features noted as Chicano English form more of a continuum amongst speakers (some may have more Chicano English features than others) than a monolithic entity spoken the same by everyone. More work also remains to be done on various other English sociolects as spoken in California.

[edit] See also

- North American Regional Phonology

- Boontling

- Chain shift

- Chicano English

- Hyphy

- Sociolect

- Sociolinguistics

- Spanglish

- Valspeak

- Vowel Shift

- California slang

[edit] References

- ^ a b c d Walt Wolfram and Ben Ward, editors (2006). American Voices: How Dialects Differ from Coast to Coast. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 140, 234–236. ISBN 978-1-4051-2108-8.

- ^ Ladefoged, Peter (1999). "American English." In Handbook of the International Phonetic Association, 41–44, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63751-1.

- ^ Labov, William, Sharon Ash, and Charles Boberg (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton-de Gruyter. p. 68. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.

- ^ Jorge Hankamer WebFest

- ^ Mary Kawena Pukui, Samuel H. Elbert & Esther T. Mookini, The Pocket Hawaiian Dictionary (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1983)

- ^ Joel Gazis-Sax (1998). "He Bans the F-Word". http://www.notfrisco.com/nortoniana/notfrisco.html. Retrieved on 2007-04-24.

[edit] Further reading

- Vowels and Consonants: An Introduction to the Sounds of Languages. Peter Ladefoged, 2003. Blackwell Publishing.

- Language in Society: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. Suzanne Romaine, 2000. Oxford University Press.

- How We Talk: American Regional English Today. Allan Metcalf, 2000. Houghton Mifflin.

[edit] External links

- Do you speak American? PBS

- Penelope Eckert, Vowel Shifts

- Phonological Atlas of North America

- A hella new specifier Paper by Rachelle Waksler discussing usage of hella

- Word Up: Social Meanings of Slang in California Youth Culture by Mary Bucholtz Ph.D., UC Santa Barbara department of Linguistics Includes discussion of "hella"