Telecine

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Telecine (pronounced /ˈtɛləˌsɪni/, /ˌtɛləˈsɪni/, ˌtɛləˈsɪnə/, also /ˌtɛləˈsiːn/ — "tel-e-Sin-ee"; "tel-e-Sin-a" as 'cine' is the same root as in 'cinema'; also "tele-seen") is the process of transferring motion picture film into video form. The term is also used to refer to the equipment used in the process.

Telecine enables a motion picture, captured originally on film, to be viewed with standard video equipment, such as televisions, video cassette decks or computers. This allows producers and distributors working in film to release their products on video and allows producers to use video production equipment to complete their film projects. The word “Telecine” is a combination of “television” and “cinema.” Within the film industry, it is also referred to as a TK, as TC is already used to designate time code.

Contents |

[edit] History of telecine

With the advent of popular television, broadcasters realized they needed more than live programming. By turning to film-originated material, they would have access to the wealth of films made for the cinema in addition to recorded television programming on film that could be aired at different times. However, the difference in frame rates between film (generally 24 frame/s) and television (30 or 25 frame/s) meant that simply playing a film into a television camera would result in flickering when the film frame was changed in mid-field of the TV frame.

Originally the kinescope was used to record the image off a television display to film, synchronized to the TV scan rate. This could then be re-played directly into a video camera for re-display.[1] Non-live programming could also be filmed using the same cameras, edited mechanically as normal, and then played back for TV. As the film was run at the same speed as the television, the flickering was eliminated. Various displays, including projectors for these "video rate films", slide projectors and movie cameras were often combined into a "film chain", allowing the broadcaster to cue up various forms of media and switch between them by moving a mirror or prism. Color was supported by using a multi-tube video camera and prisms to separate the original color signal and feeding the red, green and blue to separate tubes.

However, this still left film shot at cinema rates as a problem. The obvious solution is to simply speed up the film to match the television frame rates, but this, at least in the case of NTSC, is rather obvious to the eye and ear. This problem is not difficult to fix, however; the solution being to periodically play a selected frame twice. For NTSC, the difference in frame rates can be corrected by showing every fourth frame of film twice, although this does require the sound to be handled separately to avoid "skipping" effects. A more convincing technique is to use "2:3 pulldown", which turns every other frame of the film into three fields of video, which results in a much smoother display. PAL uses a similar system, "2:2 pulldown". These projectors could be included into existing film chain systems, allowing cinematic films to be played directly to television. With the introduction of videotape into television processing in the 1950s, it became practical to record telecined movies to videotape for later playback. This eliminated the need for the special projectors and cameras in the broadcast studio.

Since that time, telecine has primarily been a film-to-videotape process, as opposed to film-to-air. Changes since the 1950s have primarily been in terms of equipment and physical formats, the basic concept remains the same. Home videotapes of movies used this technique, and it is not uncommon to find telecined DVDs when the source was originally recorded to videotape. The same is not true for modern DVDs of cinematic movies, which are generally recorded in their original frame rate — in these cases the DVD player itself applies telecining as required to match the capabilities of the television.

[edit] Frame rate differences

The most complex part of telecine is the synchronization of the mechanical film motion and the electronic video signal. Every time the video part of the telecine samples the light electronically, the film part of the telecine must have a frame in perfect registration and ready to photograph. This is relatively easy when the film is photographed at the same frame rate as the video camera will sample, but when this is not true, a sophisticated procedure is required to change frame rate.

To avoid the synchronisation issues, higher end establishments now use a scanning system rather than just a telecine system. This allows them to scan a distinct frame of digital video for each frame of film, providing higher quality than a telecine system would be able to achieve. Normally, best results are then achieved by using a smoothing (interpolating algorithm) rather than a frame duplication algorithm (such as 3:2 pulldown, etc) to adjust for speed differences between the film and video frame rate.

[edit] 2:2 pulldown

In countries that use the PAL or SECAM video standards, film destined for television is photographed at 25 frames per second. The PAL video standard broadcasts at 25 frames per second, so the transfer from film to video is simple; for every film frame, one video frame is captured.

Theatrical features originally photographed at 24 frame/s are simply sped up by 4% to 25 frame/s. While this is usually not noticed in the picture it causes a slightly noticeable increase in audio pitch by about one semitone, which is sometimes corrected using a pitch shifter, though pitch shifting is a recent innovation and supersedes an alternative method of telecine for 25 frame/s formats. However, a difference between the two is rarely noticed unless the original audio is compared side by side with the pitched audio.

2:2 pulldown is also used to transfer shows and movies, photographed at 30 frames per second, like "Friends" and "Oklahoma!",[2] to NTSC video, which has 60 Hz scanning rate.

Although the 4% speed increase has been standard since the early days of PAL and SECAM television, recently a new technique has gained popularity, and the resulting speed and pitch of the telecined presentation are identical to that of the original film.

This pulldown method[3] is sometimes used in order to convert 24 frame/s material to 25 frame/s. Usually, this involves a film to PAL transfer without the aforementioned 4% speedup. For film at 24 frame/s, there are 24 frames of film for every 25 frames of PAL video. In order to accommodate this mismatch in frame rate, 24 frames of film have to be distributed over 50 PAL fields. This can be accomplished by inserting a pulldown field every 12 frames, thus effectively spreading 12 frames of film over 25 fields (or “12.5 frames”) of PAL video. The method used is 2:2:2:2:2:2:2:2:2:2:2:3 (Euro) pulldown (see below).

This method was born out of a frustration with the faster, higher pitched soundtracks that traditionally accompanied films transferred for PAL and SECAM audiences. More motion pictures are beginning to be telecined this way[citation needed]. It is particularly suited for films where the soundtrack is of special importance.

[edit] 2:3 pulldown

In the United States and other countries with television using 60Hz vertical scanning frequency, video is broadcast at 29.97 frame/s. For the film's motion to be accurately rendered on the video signal, a telecine must use a technique called the 2:3 pulldown (sometimes also called 3:2 pulldown) to convert from 24 to 29.97 frame/s.

The term “pulldown” comes from the mechanical process of “pulling” the film down to advance it from one frame to the next at a repetitive rate (nominally 24 frame/s). This is accomplished in two steps. The first step is to slow down the film motion by 1/1000. This speed change is unnoticeable to the viewer, and makes the film travel at 23.976 frame/s (or 7.2 seconds longer in a 2-hour movie).

The second step of the 2:3 pulldown is distributing cinema frames into video fields. At 23.976 frame/s, there are four frames of film for every five frames of 60Hz video:

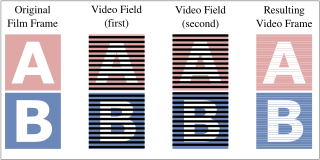

These four frames are “stretched” into five by exploiting the interlaced nature of 60Hz video. For every frame, there are actually two incomplete images or fields, one for the odd-numbered lines of the image, and one for the even-numbered lines. There are, therefore, eight fields for every four film frames, and the telecine alternately places one film frame across two fields, the next across three, the next across two, and so on. The cycle repeats itself completely after four film frames have been exposed, and in the telecine cycle these are called the A, B, C, and D frames, thus:

A 3:2 pattern is identical to this except that it is shifted by one frame. For instance, starting with film frame B, followed by frame C, yields a 3:2 pattern (B-B-B-C-C). In other words, there is no difference between the two — it is only a matter of reference. In fact, the "3:2 pulldown" notation is misleading because according to SMPTE standards the first frame of every four-frame film sequence (the A-frame) is associated with the first and second fields of one video frame, and is scanned twice, not three times.[4]

The above method is a "classic" 2:3, which was used before frame buffers allowed for holding more than one frame. The preferred method for doing a 2:3 creates only one dirty frame in every five (i.e. 3:3:2:2 or 2:3:3:2 or 2:2:3:3); while this method has a slight bit more judder, it allows for easier upconversion (the dirty frame can be dropped without losing information) and a better overall compression when encoding. The 2:3:3:2 pattern is supported by the Panasonic DVX-100B video camera under the name "Advanced Pulldown".

[edit] Other pulldown patterns

Similar techniques must be used for films shot at “silent speeds” of less than 24 frame/s (about 18frame/s), which include most silent movies themselves as well as many home movies. Sixteen frame/s (actually 15.985) to NTSC 30 frame/s (actually 29.97), pulldown should be 3:4:4:4; 16 frame/s to PAL, pulldown should be 3:3:3:3:3:3:3:4; 18 frame/s (actually 17.982) to NTSC, pulldown should be 3:3:4; 20 frame/s (actually 19.980) to NTSC, pulldown should be 3:3.

[edit] Telecine judder

The “2:3 pulldown” telecine process creates a slight error in the video signal compared to the original film frames that can be seen in the above image. This is one reason why films viewed on typical NTSC home equipment may not appear as smooth as when viewed in a cinema. The phenomenon is particularly apparent during slow, steady camera movements which appear slightly jerky when telecined. This process is commonly referred to as telecine judder. Reversing the 2-3 pulldown telecine is discussed below.

PAL material in which 2:2:2:2:2:2:2:2:2:2:2:3 pulldown has been applied, suffers from a similar lack of smoothness, though this effect is not usually called “telecine judder”. Effectively, every 12th film frame is displayed for the duration of three PAL fields (60 milliseconds), whereas the other 11 frames are all displayed for the duration of two PAL fields (40 milliseconds). This causes a slight “hiccup” in the video about twice a second. Increasingly being referred to as Euro pulldown as it largely affects European territories.

[edit] Reverse telecine (a.k.a. inverse telecine (IVTC), reverse pulldown)

Some DVD players, line doublers, and personal video recorders are designed to detect and remove 2-3 pulldown from interlaced video sources, thereby reconstructing the original 24 frame/s film frames. This technique is known as “reverse” or “inverse” telecine. Benefits of reverse telecine include high-quality non-interlaced display on compatible display devices and the elimination of redundant data for compression purposes.

Reverse telecine is crucial when acquiring film material into a digital non-linear editing system such as Sony Vegas Pro, Avid or Final Cut Pro, since these machines produce negative cut lists which refer to specific frames in the original film material. When video from a telecine is ingested into these systems, the operator usually has available a “telecine trace,” in the form of a text file, which gives the correspondence between the video material and film original. Alternatively, the video transfer may include telecine sequence markers “burned in” to the video image along with other identifying information such as time code.

It is also possible, but more difficult, to perform reverse telecine without prior knowledge of where each field of video lies in the 2-3 pulldown pattern. This is the task faced by most consumer equipment such as line doublers and personal video recorders. Ideally, only a single field needs to be identified, the rest following the pattern in lock-step. However, the 2-3 pulldown pattern does not necessarily remain consistent throughout an entire program. Edits performed on film material after it undergoes 2-3 pulldown can introduce “jumps” in the pattern if care is not taken to preserve the original frame sequence (this often happens during the editing of television shows and commercials in NTSC format). Most reverse telecine algorithms attempt to follow the 2-3 pattern using image analysis techniques, e.g. by searching for repeated fields.

Algorithms that perform 2-3 pulldown removal also usually perform the task of deinterlacing. It is possible to algorithmically determine whether video contains a 2-3 pulldown pattern or not, and selectively do either reverse telecine (in the case of film-sourced video) or deinterlacing (in the case of native video sources).

[edit] Telecine hardware

[edit] Flying spot scanner

In the United Kingdom, Rank Precision Industries was experimenting with the flying-spot scanner (FSS), which inverted the cathode ray tube (CRT) concept of scanning using a television screen. The CRT emits a pixel-sized electron beam which is converted to a photon beam through the phosphors coating the envelope. This dot of light is then focused by a lens onto the film's emulsion, and finally collected by a pickup device. In 1950 the first Rank flying spot monochrome telecine was installed at the BBC's Lime Grove Studios.[5] The advantage of the FSS is that colour analysis is done after scanning, so there can be no registration errors as can be produced by vidicon tubes where scanning is done after colour separation — it also allows simpler dichroics to be used.

In a flying spot scanner (FSS) or cathode-ray tube (CRT) telecine, a pixel-sized light beam is projected through exposed and developed motion picture film (either negative or positive) at a phosphor-coated envelope. This beam of light “scans” across the film image from left to right to record the vertical frame information. Horizontal scanning of the frame was then accomplished by moving the film past the CRT beam. This beam passes through the film image, projecting it pixel-by-pixel onto the pickup (phosphor-coated envelope). The light from the CRT passes through the film and is separated by dichroic mirrors and filters into red, green and blue bands. Photomultiplier tubes or avalanche photodiodes convert the light into separate red, green and blue electrical signals for further electronic processing. This can be accomplished in “real time”, 24 frames a second (or in some cases faster). Rank Precision-Cintel introduced the “Mark” series of FSS telecines. During this time advances were also made in CRTs, with increased light output producing a better signal-to-noise ratio and so allowing negative film to be used.

The problem with flying-spot scanners was the difference in frequencies between television field rates and film frame rates. This was solved first by the Mk. I Polygonal Prism system, which was optically sychronised to the television frame rate by the rotating prism and could be run at any frame rate. This was replaced by the Mk. II Twin Lens, and then around 1975, by the Mk. III Hopping Patch (jump scan). The Mk. III series progressed from the original “jump scan” interlace scan to the Mk. IIIB which used a progressive scan and included a digital scan converter (Digiscan) to output interlaced video. The Mk. IIIC was the most popular of the series and used a next generation Digiscan plus other improvements.

The "Mark" series was then replaced by the Ursa (1989), the first in their line of telecines capable of producing digital data in 4:2:2 color space. The Ursa Gold (1993) stepped this up to 4:4:4 and then the Ursa Diamond (1997), which incorporated many third-party improvements on the Ursa system.[6] Cintel's C-Reality and ITK's Millennium flying-spot scanner are able to do both HD and Data.

[edit] Line Array CCD

The Robert Bosch GmbH, Fernseh Div., which later became BTS inc. - Philips Digital Video Systems and is now part of Thomson's Grass Valley, introduced the world's first CCD telecine (1979), the FDL-60. The FDL-60 designed and made in Darmstadt West Germany, was the first all solid state Telecine.

Rank Cintel (ADS telecine 1982) and Marconi Company (1985) both made CCD Telecines for a short time. The Marconi B3410 sold 84 units over a three year period, and a former Marconi technician still maintains them.

In a charge-coupled device Line Array CCD telecine, a “white” light is shone through the exposed film image into a prism, which separates out the image into the three primary colors, red, green and blue. Each beam of colored light is then projected at a different CCD, one for each color. The CCD converts the light into electrical impulses which the telecine electronics modulate into a video signal which can then be recorded onto video tape or broadcast.

Philips-BTS eventually evolved the FDL 60 into the FDL 90 (1989)/ Quadra (1993). In 1996 Philips, working with Kodak, introduced the Spirit DataCine (SDC 2000), which was capable of scanning the film image at HDTV resolutions and approaching 2K (1920 Luminance and 960 Chrominace RGB) x 1556 RGB. With the data option the Spirit DataCine can be used as a motion picture film scanner outputting 2K DPX data files as 2048 x 1556 RGB. In 2000 Philips introduced the Shadow Telecine (STE), a low cost version of the Spirit with no Kodak parts. The Spirit DataCine, Cintel's C-Reality and ITK's Millennium opened the door to the technology of digital intermediates, wherein telecine tools were not just used for video outputs, but could now be used for high-resolution data that would later be recorded back out to film.[6] The Grass Valley Spirit 4k\2k\HD (2004) replaced the Spirit 1 Datacine and uses both 2K and 4k line array CCDs. (Note: the SDC-2000 did not use a color prisms and/or dichroic mirrors.)

[edit] Pulsed LED/Triggered Three CCD Camera system

In 2004, MWA Nova, Berlin introduced flashscan a new concept in film transfer systems.

Using continuous film motion, an array of multiple red, green and blue LEDs is pulsed at just the moment a frame of film is precisely positioned in front of the optics of a high-resolution, three-CCD, triggerable industrial process control camera. The LED array pulse triggers the camera and sends the single, non-interlaced image of the film frame to a digital frame store, where the electronic picture is clocked out at the applicable TV frame rate for PAL (or NTSC.) This approach enables the film speed to be varied—without flicker—in real time from three to twenty-five Frames Per Second (PAL) or six to thirty FPS for NTSC units, while introducing the appropriate pull-down for the television system involved. The output can be progressive (non-interlaced) or interlaced. The framestore also provides multiple digital and analog outputs.

The Pulsed LED/Triggered camera concept was extended to 16mm and 35mm in the company's flashtransfer system for 16 and 35mm film. A camera with larger CCD chips is used, and the company's well regarded servo driven MB51 magnetic film transport is the film handling platform. On both platforms, the color of the LED array can be varied to achieve accurate color balance, which can be further fine-tuned using the camera's black, white and gamma controls. "De-pinking" faded film and transfer of color negative film can be handled using the two color-correction systems. The SDI output enables high-end devices like digital noise reduction systems and DaVinci style color correctors to be connected.

The company introduced flashscan HD a high definition version of the 8mm/Super8 product at IBC 2008. The new unit can transfer film in HD at faster than real-time speeds. It uses a three-CMOS chip HD camera and hardware processing of the video to output all major HD formats. Software controls film motion and color correction, which can be tied to cues for real-time color correction.

[edit] Digital intermediate systems and virtual telecines

Telecine technology is increasingly merging with that of motion picture film scanners; high-resolution telecines, such as those mentioned above, can be regarded as film scanners that operate in real time.

As digital intermediate post-production becomes more common, the need to combine the traditional telecine functions of input devices, standards converters, and colour grading systems is becoming less important as the post-production chain changes to tapeless and filmless operation.

However, the parts of the workflow associated with telecines still remain, and are being pushed to the end, rather than the beginning, of the post-production chain, in the form of real-time digital grading systems and digital intermediate mastering systems, increasingly running in software on commodity computer systems. These are sometimes called virtual telecine systems.

[edit] Video cameras that produce telecined video, and "film look"

Some video cameras and consumer camcorders are able to record in progressive "24 frame/s" (actually 23.98 frame/s) or "30 frame/s" (actually 29.97 frame/s) in NTSC, or 25 frame/s (PAL) mode. Such a video has cinema-like motion characteristics and is the major component of so-called "film look" or "movie look".

For most "24 frame/s" cameras, the virtual 2:3 pulldown process is happening inside the camera. Although the camera is capturing a progressive frame at the CCD, just like a movie camera, it is then imposing an interlacing on the image to record it to tape so that it can be played back on any standard television. Not every camera handles "24 frame/s" this way, but the majority of them do.[7]

Cameras that record 25 frame/s (PAL) or 29.97 frame/s (NTSC) do not need to employ 2:3 pulldown, because every progressive frame occupies exactly two video fields. In video industry this type of encoding is called Progressive Segmented Frame (PsF). PsF is conceptually identical to 2:2 pulldown, only there is no film original to transfer from.

[edit] Digital television and high definition

Digital television and high definition standards provide several methods for encoding film material. Fifty field/s formats such as 576i50 and 1080i50 can accommodate film content using a 4% speed-up like PAL. 59.94 field/s interlaced formats such as 480i60 and 1080i60 use the same 2:3 pulldown technique as NTSC. In 59.94 frame/s progressive formats such as 480p60 and 720p60, entire frames (rather than fields) are repeated in a 2:3 pattern, accomplishing the frame rate conversion without interlacing and its associated artifacts. Other formats such as 1080p24 can decode film material at its native rate of 24 or 23.976 frame/s.

All of these coding methods are in use to some extent. In PAL countries, 25 frame/s formats remain the norm. In NTSC countries, most digital broadcasts of 24 frame/s material, both standard and high definition, continue to use interlaced formats with 2:3 pulldown. Native 24 and 23.976 frame/s formats offer the greatest image quality and coding efficiency, and are widely used in motion picture and high definition video production. However, most consumer video devices do not support these formats. Recently however, several vendors have begun selling LCD televisions in NTSC/ATSC countries that are capable of 120Hz refresh rates and plasma sets capable of 48, 72, or 96Hz refresh.[8] When combined with a 1080p24-capable source (such as most Blu-ray players), some of these sets are able to display film-based content using a pulldown scheme using whole multiples of 24, thereby avoiding the problems associated with 2:3 pulldown or the 4% speed-up used in PAL countries.

[edit] DVDs

On DVDs, telecined material may be either hard telecined, or soft telecined. In the hard-telecined case, video is stored on the DVD at the playback framerate (29.97 frame/s for NTSC, 25 frame/s for PAL), using the telecined frames as shown above. In the soft-telecined case, the material is stored on the DVD at the film rate (24 or 23.976 frame/s) in the original progressive format, with special flags inserted into the MPEG-2 video stream that instruct the DVD player to repeat certain fields so as to accomplish the required pulldown during playback.[9] Progressive scan DVD players additionally offer output at 480p by using these flags to duplicate frames rather than fields.

NTSC DVDs are often soft telecined, although lower-quality hard-telecined DVDs exist. In the case of PAL DVDs using 2:2 pulldown, the difference between soft and hard telecine vanishes, and the two may be regarded as equal. In the case of PAL DVDs using 2:3 pulldown, either soft or hard telecining may be applied.

[edit] See also

- Factors causing HDTV Blur.

- Telecine (piracy), a pirated copy of a film created with a telecine.

- Da Vinci Systems and Pandora Int.'s color grading and editing systems.

- Cintel telecine equipment.

- Color suite

- For means of putting video on film, see telerecording (UK) and kinescope (US).

[edit] References

- ^ Pincus, Edward and Ascher, Steven. (1984). The Filmmaker's Handbook. Plume. p. 368-9 ISBN 0-452-25526-0

- ^ "Home Theater and High Fidelity, Progressive Scan DVDs and deinterlacing"". http://www.hometheaterhifi.com/volume_7_4/dvd-benchmark-part-5-progressive-10-2000.html.

- ^ MPlayer FAQ

- ^ "Charles Poynton, Digital Video and HDTV: Algorithms and Interfaces". http://books.google.com/books?id=ra1lcAwgvq4C&pg=RA1-PA604&vq=illumination&dq=poynton&source=gbs_search_s&sig=xbuHZkXUegarB-2bHG52BNvZVdQ#PRA1-PA610,M1.

- ^ Some key dates in Cintel's history

- ^ a b Holben, Jay (May 1999). “From Film to Tape” American Cinematographer Magazine, pp. 108–122.

- ^ "Jay Holben, More Detail on 24p". http://www.dv.com/columns/columns_item.php?articleId=196603515.

- ^ List of displays that support pulldown at multiples of the original frame rate

- ^ DVDFILE.COM: What The Heck Is 3:2 Pulldown?

[edit] External links

- XYHD: How a 3:2 Pull Down Cadence works when converting Film to Video

- Photographs of cine film types and reels. Further information on telecine transfer

- TMTV: Technical information on HDDTT film transfers

- IVTC Explained (brief)

- Explanation of telecine methods

- EBU I42 2004: Telecines for broadcasters — Technical information

- The Big Picture — 3:2 Pulldown and Inverse Telecine — In-depth explanation of interlaced and progressive frames, and the telecine process

- Tutorial Regarding Methods of Inverse Telecining

- TIG: The Telecine Internet Group (mailinglist and wiki)

- A Memories3 Technology - A frame by frame process with a custom engineered telecine machine

- Frame rate test video files

Hardware Products:

- Cintel - Manufacturer of CRT and CCD based telecines and scanners

- Moviestuff - Manufacturer of 16 mm and 8 mm film telecine units for home transfers.

- MWA Nova - Manufacturer of SD and HD telecines

- flashscan8.us -US/Canadian Distributor of MWA SD and HD telecines and other products

- Lasergraphics - Film scanner manufacturer

- Digital Film Technology - Manufacturer of CCD based telecines and data scanners, formerly ThomsonGrassValley, previously Philips, BTS, Bosch

- Building a Telecine Machine

|

||||||||||||||