Facial expression

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2009) |

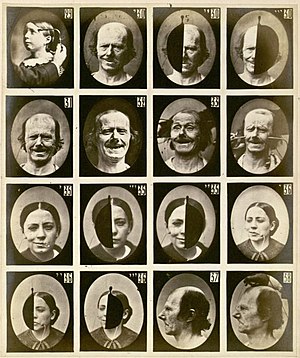

A facial expression results from one or more motions or positions of the muscles of the face. These movements convey the emotional state of the individual to observers. Facial expressions are a form of nonverbal communication. They are a primary means of conveying social information among humans, but also occur in most other mammals and some other animal species.

Humans can adopt a facial expression as a voluntary action. However, because expressions are closely tied to emotion, they are more often involuntary. It can be nearly impossible to avoid expressions for certain emotions, even when it would be strongly desirable to do so; a person who is trying to avoid insult to an individual he or she finds highly unattractive might nevertheless show a brief expression of disgust before being able to reassume a neutral expression. The close link between emotion and expression can also work in the other direction; it has been observed that voluntarily assuming an expression can actually cause the associated emotion.[citation needed]

Some expressions can be accurately interpreted even between members of different species- anger and extreme contentment being the primary examples. Others, however, are difficult to interpret even in familiar individuals. For instance, disgust and fear can be tough to tell apart.[citation needed]

Because faces have only a limited range of movement, expressions rely upon fairly minuscule differences in the proportion and relative position of facial features, and reading them requires considerable sensitivity to same. Some faces are often falsely read as expressing some emotion, even when they are neutral, because their proportions naturally resemble those another face would temporarily assume when emoting.[citation needed]

Contents |

[edit] Universality

| This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2009) |

Charles Darwin noted in his book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals:

- ...the young and the old of widely different races, both with man and animals, express the same state of mind by the same movements.[citation needed]

Still, up to the mid-20th century most anthropologists believed that facial expressions were entirely learned and could therefore differ among cultures. Studies eventually supported Darwin's belief to a large degree, particularly for expressions of anger, sadness, fear, surprise, disgust, contempt, happiness and caring.[citation needed]

The people of New Guinea called South Fore were chosen as subjects for one such survey. The study consisted of 189 adults and 130 children from among a very isolated population, as well as twenty three members of the culture who lived a less isolated lifestyle as a control group. Participants were told a story that described one particular emotion; they were then shown three pictures (two for children) of facial expressions and asked to match the picture which expressed the story's emotion.

While the isolated South Fore people could identify emotions with the same accuracy as the non-isolated control group, problems associated with the study include the fact that both fear and surprise were constantly misidentified. The study concluded that certain facial expressions correspond to particular emotions, regardless of cultural background, and regardless of whether or not the culture has been isolated or exposed to the mainstream.

[edit] Communication

A person's face, especially their eyes, creates the most obvious and immediate cues that lead to the formation of impressions.[1] This article discusses eyes and facial expressions and the effect they have on interpersonal communication.

A person's eyes reveal much about how they are feeling, or what they are thinking. Blink rate can reveal how nervous or at ease a person may be. Research by Boston College professor Joe Tecce suggests that stress levels are revealed by blink rates. He supports his data with statistics on the relation between the blink rates of presidential candidates and their success in their races. Tecce claims that the faster blinker in the presidential debates has lost every election since 1980.[2] Though Tecce's data is interesting, it is important to recognize that non-verbal communication is multi-channeled, and focusing on only one aspect is reckless. Nervousness can also be measured by examining each candidates' perspiration, eye contact and stiffness.[3]

Eye contact is another major aspect of facial communication. Some have hypothesized that this is due to infancy, as humans are one of the few mammals who maintain regular eye contact with their mother while nursing.[4] Eye contact serves a variety of purposes. It regulates conversations, shows interest or involvement, and establishes a connection with others.

- Eye contact regulates conversational turn taking, communicates involvement and interest, manifests warmth, and establishes connections with others…[and it can command attention, be flirtatious, or seem cold and intimidating… [it] invites conversation. Lack of eye contact is usually perceived to be rude or inattentive.[3]

But different cultures have different rules for eye contact. Certain Asian cultures can perceive direct eye contact as a way to signal competitiveness, which in many situations may prove to be inappropriate. Others lower their eyes to signal respect, but in western cultures this could be misinterpretted as lacking self-confidence.

Even beyond the idea of eye contact, eyes communicate more data than a person even consciously expresses. Pupil dilation is a significant cue to a level of excitement, pleasure, or attraction. Dilated pupils indicate greater affection or attraction, while constricted pupils send a colder signal.

The face as a whole indicates much about human moods as well. Specific emotional states, such as happiness or sadness, are expressed through a smile or a frown, respectively. There are seven universally recognized emotions shown through facial expressions: fear, anger, surprise, contempt, disgust, happiness, and sadness. Regardless of culture, these expressions are the same. However, the same emotion from a specific facial expression may be recognized by a culture, but the same intensity of emotion may not be perceived. For example, studies have shown that Asian cultures tend to rate images of facial emotions as less intense than non-Asian cultures surveyed. This difference can be explained by display rules, which are culture-specific guidelines for behavior appropriateness. In some countries, it may be more rude to display an emotion than in another. Showing anger toward another member in a group may create problems and disharmony, but if displayed towards a competitive rival, it could create in-group cohesion.[citation needed]

[edit] Facial expressions

Some examples of feelings that can be expressed are:

- Anger

- Concentration

- Confusion

- Contempt

- Desire

- Disgust

- Excitement

- Fear

- Happiness

- Sadness

- Surprise

- Glare

- Snarl, mainly involving the levator labii superioris alaeque nasi muscle

[edit] The muscles of facial expression

See also: facial muscles.

- Auricularis anterior muscle

- Buccinator muscle

- Corrugator supercilii muscle

- Depressor anguli oris muscle

- Depressor labii inferioris muscle

- Depressor septi nasi muscle

- Frontalis muscle

- Levator anguli oris muscle

- Levator labii superioris muscle

- Levator labii superioris alaeque nasi muscle

- Mentalis muscle

- modiolus

- Nasalis muscle

- Orbicularis oculi muscle

- Orbicularis oris muscle

- Platysma muscle

- Procerus muscle

- Risorius muscle

- Zygomaticus major muscle

- Zygomaticus minor muscle

[edit] References

- ^ Freitas-Magalhães, A. (2007). The Psychology of Emotions: The Allure of Human Face. Oporto: University Fernando Pessoa Press

- ^ “In the blink of an eye.” (1996, October 21). Newsweek.

- ^ a b Rothwell, J. Dan. In the Company of Others: An Introduction to Communication. United States: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

- ^ Spitz, Rene A., and Wolf, K. M. “The Smiling Response: A Contribution to the Ontogenesis of Social Relations.” Genetic Psychology Monographs. 34 (August 1946). P. 57-125.

[edit] See also

- Affect display

- Paul Ekman, Facial Action Coding System

- Metacommunicative competence

- Laughter, Gelotology, Freitas-Magalhães

- Gurn

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Facial expression |

- Facial Emotion Expression Lab

- Antithesis in factial expressions

- Facial Expression at Nonverbal World

- The Naked Face, August 5, 2002. Annals of Psychology

- Facial Expressions Resources Page contains links to research concerning facial expressions