Central limit theorem

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2008) |

In probability theory, the central limit theorem (CLT) states conditions under which the sum of a sufficiently large number of independent random variables, each with finite mean and variance, will be approximately normally distributed (Rice 1995). More generally, a central limit theorem is any of a set of weak-convergence results in probability theory. They all express the fact that a sum of many independent random variables will tend to be distributed according to one of a small set of "attractor" (i.e. stable) distributions.

Since many real populations yield distributions with finite variance, this explains the prevalence of the normal probability distribution. For other generalizations for finite variance which do not require identical distribution, see Lindeberg's condition, Lyapunov's condition, Gnedenko and Kolmogorov states.

[edit] History

Tijms (2004, p.169) writes:

| “ | The central limit theorem has an interesting history. The first version of this theorem was postulated by the French-born mathematician Abraham de Moivre who, in a remarkable article published in 1733, used the normal distribution to approximate the distribution of the number of heads resulting from many tosses of a fair coin. This finding was far ahead of its time, and was nearly forgotten until the famous French mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace rescued it from obscurity in his monumental work Théorie Analytique des Probabilités, which was published in 1812. Laplace expanded De Moivre's finding by approximating the binomial distribution with the normal distribution. But as with De Moivre, Laplace's finding received little attention in his own time. It was not until the nineteenth century was at an end that the importance of the central limit theorem was discerned, when, in 1901, Russian mathematician Aleksandr Lyapunov defined it in general terms and proved precisely how it worked mathematically. Nowadays, the central limit theorem is considered to be the unofficial sovereign of probability theory. | ” |

Sir Francis Galton (Natural Inheritance, 1889) described the Central Limit Theorem as:

| “ | I know of scarcely anything so apt to impress the imagination as the wonderful form of cosmic order expressed by the "Law of Frequency of Error". The law would have been personified by the Greeks and deified, if they had known of it. It reigns with serenity and in complete self-effacement, amidst the wildest confusion. The huger the mob, and the greater the apparent anarchy, the more perfect is its sway. It is the supreme law of Unreason. Whenever a large sample of chaotic elements are taken in hand and marshaled in the order of their magnitude, an unsuspected and most beautiful form of regularity proves to have been latent all along. | ” |

A thorough account of the theorem's history, detailing Laplace's foundational work, as well as Cauchy's, Bessel's and Poisson's contributions, is provided by Hald.[1] Two historic accounts, one covering the development from Laplace to Cauchy, the second the contributions by von Mises, Pólya, Lindeberg, Lévy, and Cramér during the 1920s, are given by Hans Fischer.[2] A period around 1935 is described in (Le Cam 1986). See Bernstein (1945) for a historical discussion focusing on the work of Pafnuty Chebyshev and his students Andrey Markov and Aleksandr Lyapunov that led to the first proofs of the C.L.T. in a general setting.

[edit] Classical central limit theorem

The central limit theorem is also known as the second fundamental theorem of probability. (The Law of large numbers is the first.)

Let X1, X2, X3, ... Xn be a sequence of n independent and identically distributed (i.i.d) random variables each having finite values of expectation µ and variance σ2 > 0. The central limit theorem states that as the sample size n increases[3] [4] , the distribution of the sample average of these random variables approaches the normal distribution with a mean µ and variance σ2 / n irrespective of the shape of the original distribution.

Let the sum of n random variables be Sn, given by

Sn = X1 + ... + Xn. Then, defining a new random variable

the distribution of Zn converges towards the standard normal distribution N(0,1) as n approaches ∞ (this is convergence in distribution).[3] This is often written as

where

is the sample mean.

This means: if Φ(z) is the cumulative distribution function of N(0,1), then for every real number z, we have

or,

[edit] Proof of the central limit theorem

For a theorem of such fundamental importance to statistics and applied probability, the central limit theorem has a remarkably simple proof using characteristic functions. It is similar to the proof of a (weak) law of large numbers. For any random variable, Y, with zero mean and unit variance (var(Y) = 1), the characteristic function of Y is, by Taylor's theorem,

where o (t2 ) is "little o notation" for some function of t that goes to zero more rapidly than t2. Letting Yi be (Xi − μ)/σ, the standardized value of Xi, it is easy to see that the standardized mean of the observations X1, X2, ..., Xn is

By simple properties of characteristic functions, the characteristic function of Zn is

But, this limit is just the characteristic function of a standard normal distribution, N(0,1), and the central limit theorem follows from the Lévy continuity theorem, which confirms that the convergence of characteristic functions implies convergence in distribution.

[edit] Convergence to the limit

The central limit theorem gives only an asymptotic distribution. As an approximation for a finite number of observations, it provides a reasonable approximation only when close to the peak of the normal distribution; it requires a very large number of observations to stretch into the tails.

If the third central moment E((X1 − μ)3) exists and is finite, then the above convergence is uniform and the speed of convergence is at least on the order of 1/n½ (see Berry-Esséen theorem).

The convergence to the normal distribution is monotonic, in the sense that the entropy of Zn increases monotonically to that of the normal distribution, as proven in Artstein, Ball, Barthe and Naor (2004).

The central limit theorem applies in particular to sums of independent and identically distributed discrete random variables. A sum of discrete random variables is still a discrete random variable, so that we are confronted with a sequence of discrete random variables whose cumulative probability distribution function converges towards a cumulative probability distribution function corresponding to a continuous variable (namely that of the normal distribution). This means that if we build a histogram of the realisations of the sum of n independent identical discrete variables, the curve that joins the centers of the upper faces of the rectangles forming the histogram converges toward a Gaussian curve as n approaches infinity. The binomial distribution article details such an application of the central limit theorem in the simple case of a discrete variable taking only two possible values.

[edit] Relation to the law of large numbers

The law of large numbers as well as the central limit theorem are partial solutions to a general problem: "What is the limiting behavior of Sn as n approaches infinity?" In mathematical analysis, asymptotic series is one of the most popular tools employed to approach such questions.

Suppose we have an asymptotic expansion of ƒ(n):

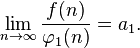

dividing both parts by  and taking the limit will produce a1 — the coefficient at the highest-order term in the expansion representing the rate at which ƒ(n) changes in its leading term.

and taking the limit will produce a1 — the coefficient at the highest-order term in the expansion representing the rate at which ƒ(n) changes in its leading term.

Informally, one can say: "ƒ(n) grows approximately as a1 φ(n)". Taking the difference between ƒ(n) and its approximation and then dividing by the next term in the expansion we arrive to a more refined statement about ƒ(n):

here one can say that: "the difference between the function and its approximation grows approximately as a2 φ2(n)" The idea is that dividing the function by appropriate normalizing functions and looking at the limiting behavior of the result can tell us much about the limiting behavior of the original function itself.

Informally, something along these lines is happening when Sn is being studied in classical probability theory. Under certain regularity conditions, by The Law of Large Numbers, Sn → μ and by The Central Limit Theorem,

where ξ is distributed as N(0, σ2), which provides values of first two constants in informal expansion:

It could be shown[citation needed] that if X1, X2, X3, ... are i.i.d. and  for some

for some  then

then  hence

hence  is the largest power of n which if serves as a normalizing function would provide a non-trivial (non-zero) limiting behavior. Interestingly enough, The Law of the Iterated Logarithm tells us what is happening "in between" The Law of Large Numbers and The Central Limit Theorem. Specifically it says that the normalizing function

is the largest power of n which if serves as a normalizing function would provide a non-trivial (non-zero) limiting behavior. Interestingly enough, The Law of the Iterated Logarithm tells us what is happening "in between" The Law of Large Numbers and The Central Limit Theorem. Specifically it says that the normalizing function  intermediate in size between n of The Law of Large Numbers and

intermediate in size between n of The Law of Large Numbers and  of the central limit theorem provides a non-trivial limiting behavior.

of the central limit theorem provides a non-trivial limiting behavior.

[edit] Alternative statements of the theorem

[edit] Density functions

The density of the sum of two or more independent variables is the convolution of their densities (if these densities exist). Thus the central limit theorem can be interpreted as a statement about the properties of density functions under convolution: the convolution of a number of density functions tends to the normal density as the number of density functions increases without bound, under the conditions stated above.

[edit] Characteristic functions

Since the characteristic function of a convolution is the product of the characteristic functions of the densities involved, the central limit theorem has yet another restatement: the product of the characteristic functions of a number of density functions becomes close to the characteristic function of the normal density as the number of density functions increases without bound, under the conditions stated above. However, to state this more precisely, an appropriate scaling factor needs to be applied to the argument of the characteristic function.

An equivalent statement can be made about Fourier transforms, since the characteristic function is essentially a Fourier transform.

[edit] Extensions to the theorem

[edit] Multidimensional central limit theorem

We can easily extend proofs using characteristic functions for cases where each individual Xi is an independent and identically distributed random vector, with mean vector μ and covariance matrix Σ (amongst the individual components of the vector). Now, if we take the summations of these vectors as being done componentwise, then the Multidimensional central limit theorem states that when scaled, these converge to a multivariate normal distribution.

[edit] Products of positive random variables

The logarithm of a product is simply the sum of the logarithms of the factors. Therefore when the logarithm of a product of random variables that take only positive values approaches a normal distribution, the product itself approaches a log-normal distribution. Many physical quantities (especially mass or length, which are a matter of scale and cannot be negative) are the products of different random factors, so they follow a log-normal distribution.

Whereas the central limit theorem for sums of random variables requires the condition of finite variance, the corresponding theorem for products requires the corresponding condition that the density function be square-integrable (see Rempala 2002).

[edit] Lack of identical distribution

The central limit theorem also applies in the case of sequences that are not identically distributed, provided one of a number of conditions apply.

[edit] Lyapunov condition

Let Xn be a sequence of independent random variables defined on the same probability space. Assume that Xn has finite expected value μn and finite standard deviation σn. We define

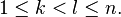

If for some δ > 0, the expected values ![\mathbb{E}[|X_{i}|^{2+\delta}]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/c/0/d/c0da4906d6a2f9bf105956579c58873f.png) are finite for every

are finite for every  and the Lyapunov's condition

and the Lyapunov's condition

is satisfied, then the distribution of the random variable

converges to the standard normal distribution N(0,1).

[edit] Lindeberg condition

In the same setting and with the same notation as above, we can replace the Lyapunov condition with the following weaker one (from Lindeberg in 1920). For every ε > 0

where E( U : V > c) is the expectation of the random variable U |{V > c} whose value is U if V > c and zero otherwise. Then the distribution of the standardized sum Zn converges towards the standard normal distribution N(0,1).

[edit] Beyond the classical framework

Asymptotic normality, that is, convergence to the normal distribution after appropriate shift and rescaling, is a phenomenon much more general than the classical framework treated above, namely, sums of independent random variables (or vectors). New frameworks are revealed from time to time; no single unifying framework is available for now.

[edit] Central limit theorem under weak dependence

A useful generalization of a sequence of independent, identically distributed random variables is a mixing random process in discrete time; "mixing" means, roughly, that random variables far apart from one another are nearly independent. Several kinds of mixing are used in ergodic theory and probability theory. See especially strong mixing (also called α-mixing) defined by  where α(n) is so-called strong mixing coefficient.

where α(n) is so-called strong mixing coefficient.

A simplified formulation of the central limit theorem under strong mixing is given in (Billingsley 1995, Theorem 27.4):

Theorem. Suppose that  is stationary and α-mixing with

is stationary and α-mixing with  and that

and that  and

and  . Denote

. Denote  then the limit

then the limit  exists, and if

exists, and if  then

then  converges in distribution to N(0,1).

converges in distribution to N(0,1).

In fact,  where the series converges absolutely.

where the series converges absolutely.

The assumption  cannot be omitted, since the asymptotic normality fails for

cannot be omitted, since the asymptotic normality fails for  where Yn are another stationary sequence.

where Yn are another stationary sequence.

For the theorem in full strength see (Durrett 1996, Sect. 7.7(c), Theorem (7.8)); the assumption  is replaced with

is replaced with  and the assumption αn = O(n − 5) is replaced with

and the assumption αn = O(n − 5) is replaced with  Existence of such δ > 0 ensures the conclusion.

Existence of such δ > 0 ensures the conclusion.

[edit] Martingale central limit theorem

Theorem. Let a martingale Mn satisfy

in probability as n tends to infinity,

in probability as n tends to infinity,- for every

as n tends to infinity,

as n tends to infinity,

then  converges in distribution to N(0,1) as n tends to infinity.

converges in distribution to N(0,1) as n tends to infinity.

See (Durrett 1996, Sect. 7.7, Theorem (7.4)) or (Billingsley 1995, Theorem 35.12).

Caution: The restricted expectation E(X;A) should not be confused with the conditional expectation

[edit] Central limit theorem for convex bodies

Theorem (Klartag 2007, Theorem 1.2). There exists a sequence  for which the following holds. Let

for which the following holds. Let  , and let random variables

, and let random variables  have a log-concave joint density f such that

have a log-concave joint density f such that  for all

for all  and

and  for all

for all  Then the distribution of

Then the distribution of  is

is  -close to N(0,1) in the total variation distance.

-close to N(0,1) in the total variation distance.

These two  -close distributions have densities (in fact, log-concave densities), thus, the total variance distance between them is the integral of the absolute value of the difference between the densities. Convergence in total variation is stronger than weak convergence.

-close distributions have densities (in fact, log-concave densities), thus, the total variance distance between them is the integral of the absolute value of the difference between the densities. Convergence in total variation is stronger than weak convergence.

An important example of a log-concave density is a function constant inside a given convex body and vanishing outside; it corresponds to the uniform distribution on the convex body, which explains the term "central limit theorem for convex bodies".

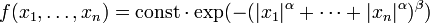

Another example:  where α > 1 and αβ > 1. If β = 1 then

where α > 1 and αβ > 1. If β = 1 then  factorizes into

factorizes into  which means independence of

which means independence of  In general, however, they are dependent.

In general, however, they are dependent.

The condition  ensures that

ensures that  are of zero mean and uncorrelated; still, they need not be independent, nor even pairwise independent. By the way, pairwise independence cannot replace independence in the classical central limit theorem (Durrett 1996, Section 2.4, Example 4.5).

are of zero mean and uncorrelated; still, they need not be independent, nor even pairwise independent. By the way, pairwise independence cannot replace independence in the classical central limit theorem (Durrett 1996, Section 2.4, Example 4.5).

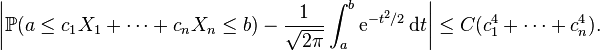

Here is a Berry-Esseen type result.

Theorem (Klartag 2008, Theorem 1). Let  satisfy the assumptions of the previous theorem, then

satisfy the assumptions of the previous theorem, then

for all  here

here  is a universal (absolute) constant. Moreover, for every

is a universal (absolute) constant. Moreover, for every  such that

such that

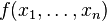

A more general case is treated in (Klartag 2007, Theorem 1.1). The condition  is replaced with much weaker conditions: E(Xk) = 0,

is replaced with much weaker conditions: E(Xk) = 0,  E(XkXl) = 0 for

E(XkXl) = 0 for  The distribution of

The distribution of  need not be approximately normal (in fact, it can be uniform). However, the distribution of

need not be approximately normal (in fact, it can be uniform). However, the distribution of  is close to N(0,1) (in the total variation distance) for most of vectors

is close to N(0,1) (in the total variation distance) for most of vectors  according to the uniform distribution on the sphere

according to the uniform distribution on the sphere

[edit] Central limit theorem for lacunary trigonometric series

Theorem (Salem - Zygmund). Let U be a random variable distributed uniformly on (0, 2π), and Xk = rk cos(nkU + ak), where

- nk satisfy the lacunarity condition: there exists q > 1 such that nk+1 ≥ qnk for all k,

- rk are such that

- 0 ≤ ak < 2π.

Then

converges in distribution to N(0, 1/2).

See (Zygmund 1959, Sect. XVI.5, Theorem (5-5)) or (Gaposhkin 1966, Theorem 2.1.13).

[edit] Central limit theorem for Gaussian polytopes

Theorem (Barany & Vu 2007, Theorem 1.1). Let A1, ..., An be independent random points on the plane R2 each having the two-dimensional standard normal distribution. Let Kn be the convex hull of these points, and Xn the area of Kn Then

converges in distribution to N(0,1) as n tends to infinity.

The same holds in all dimensions (2, 3, ...).

The polytope Kn is called Gaussian random polytope.

A similar result holds for the number of vertices (of the Gaussian polytope), the number of edges, and in fact, faces of all dimensions (Barany & Vu 2007, Theorem 1.2).

[edit] Central limit theorem for linear functions of orthogonal matrices

A linear function of a matrix M is a linear combination of its elements (with given coefficients),  where A is the matrix of the coefficients; see Trace_(linear_algebra)#Inner product.

where A is the matrix of the coefficients; see Trace_(linear_algebra)#Inner product.

A random orthogonal matrix is said to be distributed uniformly, if its distribution is the normalized Haar measure on the orthogonal group O(n,R); see Rotation matrix#Uniform random rotation matrices.

Theorem (Meckes 2008). Let M be a random orthogonal n×n matrix distributed uniformly, and A a fixed n×n matrix such that  and let

and let  Then the distribution of X is close to N(0,1) in the total variation metric up to

Then the distribution of X is close to N(0,1) in the total variation metric up to

[edit] Central limit theorem for subsequences

Theorem (Gaposhkin 1966, Sect. 1.5). Let random variables  be such that

be such that  weakly in L2(Ω) and

weakly in L2(Ω) and  weakly in L1(Ω). Then there exist integers

weakly in L1(Ω). Then there exist integers  such that

such that  converges in distribution to N(0, 1) as k tends to infinity.

converges in distribution to N(0, 1) as k tends to infinity.

[edit] Applications and examples

There are a number of useful and interesting examples and applications arising from the central limit theorem (Dinov, Christou & Sanchez 2008). See e.g. [1], presented as part of the SOCR CLT Activity.

- The probability distribution for total distance covered in a random walk (biased or unbiased) will tend toward a normal distribution.

- Flipping a large number of coins will result in a normal distribution for the total number of heads (or equivalently total number of tails).

From another viewpoint, the central limit theorem explains the common appearance of the 'Bell Curve' in density estimates applied to real world data. In cases like electronic noise, examination grades, and so on, we can often regard a single measured value as the weighted average of a large number of small effects. Using generalisations of the central limit theorem, we can then see that this would often (though not always) produce a final distribution that is approximately normal.

In general, the more like the sum of independent variables with equal influence on the result a measurement is, the more normality it exhibits. This justifies the common use of this distribution to stand in for the effects of unobserved variables in models like the linear model.

[edit] Signal processing

Signals can be smoothed by applying a Gaussian filter, which is just the convolution of a signal with an appropriately scaled Gaussian function. Due to the central limit theorem this smoothing can be approximated by several filter steps that can be computed much faster, like the simple moving average.

The central limit theorem implies that to achieve a Gaussian of variance σ2 n filters with windows of variances  with

with  must be applied.

must be applied.

[edit] See also

- Diversification (finance)

- Illustration of the central limit theorem

- Law of large numbers — weaker conclusion in the same context

- Log-normal distribution — what we get when we multiply random variables in a similar context to the Central limit theorem

- Berry–Esséen theorem –— error bounds on normal approximations based on the central limit theorem

[edit] Notes

- ^ Andreas Hald, History of Mathematical Statistics from 1750 to 1930, Ch.17.

- ^ Hans Fischer: (1) "The Central Limit Theorem from Laplace to Cauchy: Changes in Stochastic Objectives and in Analytical Methods"; (2) "The Central Limit Theorem in the Twenties".

- ^ a b For decades, large sample size was set as n > 29; however, research since 1990, has indicated larger samples, such as 100 or 250, might be needed if the population is skewed far from normal: the more skew, the larger the sample needed. The conditions might be rare, but critical when they occur: computer animations are used to illustrate the cases. The cutoff with n > 29 has allowed Student-t tables to format in limited pages; however, that sample size might be too small. See below "Using graphics and simulation.." by Marasinghe et al, and see "Identification of Misconceptions in the Central Limit Theorem and Related Concepts and Evaluation of Computer Media as a Remedial Tool" by Yu, Chong Ho and Dr. John T. Behrens, Arizona State University & Spencer Anthony, Univ. of Oklahoma, Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, presented April 19, 1995, paper revised in Feb 12, 1997, webpage (accessed 2007-10-25): CWisdom-rtf.

- ^ Marasinghe, M., Meeker, W., Cook, D. & Shin, T.S.(1994 August), "Using graphics and simulation to teach statistical concepts", Paper presented at the Annual meeting of the American Statistician Association, Toronto, Canada.

[edit] References

- Henk Tijms, Understanding Probability: Chance Rules in Everyday Life, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- S. Artstein, K. Ball, F. Barthe and A. Naor (2004), "Solution of Shannon's Problem on the Monotonicity of Entropy", Journal of the American Mathematical Society 17, 975–982. Also author's site.

- S.N.Bernstein, On the work of P.L.Chebyshev in Probability Theory, Nauchnoe Nasledie P.L.Chebysheva. Vypusk Pervyi: Matematika. (Russian) [The Scientific Legacy of P. L. Chebyshev. First Part: Mathematics] Edited by S. N. Bernstein.] Academiya Nauk SSSR, Moscow-Leningrad, 1945. 174 pp.

- G. Rempala and J. Wesolowski, "Asymptotics of products of sums and U-statistics", Electronic Communications in Probability, vol. 7, pp. 47–54, 2002.

- Dinov, Ivo; Christou, Nicolas; Sanchez, Juana (2008), "Central Limit Theorem: New SOCR Applet and Demonstration Activity", Journal of Statistics Education (ASA) 16 (2). Also at ASA/JSE.

- Billingsley, Patrick (1995), Probability and Measure (Third ed.), John Wiley & sons, ISBN 0-471-00710-2

- Rice, John (1995), Mathematical Statistics and Data Analysis (Second ed.), Duxbury Press, ISBN 0-534-20934-3

- Durrett, Richard (1996), Probability: theory and examples (Second ed.)

- Klartag, Bo'az (2007), "A central limit theorem for convex sets", Inventiones Mathematicae 168, 91–131. Also arXiv.

- Klartag, Bo'az (2008), "A Berry-Esseen type inequality for convex bodies with an unconditional basis", Probability Theory and Related Fields. Also arXiv.

- Le Cam, Lucien (1986), "The central limit theorem around 1935", Statistical Science 1:1, 78–91.

- Zygmund, Antoni (1959), Trigonometric series, II, Cambridge.

- Barany, Imre; Vu, Van (2007), "Central limit theorems for Gaussian polytopes", The Annals of Probability (Institute of Mathematical Statistics) 35 (4): 1593–1621, doi:. Also arXiv.

- Meckes, Elizabeth (2008), "Linear functions on the classical matrix groups", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 360: 5355–5366, doi:. Also arXiv.

- Gaposhkin, V.F. (1966), "Lacunary series and independent functions", Russian Math. Surveys 21 (6): 1–82, doi:.

[edit] External links

- Animated examples of the CLT

- Central Limit Theorem Java

- Central Limit Theorem interactive simulation to experiment with various parameters

- CLT in NetLogo (Connected Probability - ProbLab) interactive simulation w/ a variety of modifiable parameters

- General Central Limit Theorem Activity & corresponding SOCR CLT Applet (Select the Sampling Distribution CLT Experiment from the drop-down list of SOCR Experiments)

- Generate sampling distributions in Excel Specify arbitrary population, sample size, and sample statistic.

- [2] Another proof.

- CAUSEweb.org is a site with many resources for teaching statistics including the Central Limit Theorem

- The Central Limit Theorem by Chris Boucher, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Eric W. Weisstein, Central Limit Theorem at MathWorld.

- Animations for the Central Limit Theorem by Yihui Xie using the R package animation

- A visualization of the Central Limit Theorem from Portfolio Monkey.

![\left[\varphi_Y\left({t \over \sqrt{n}}\right)\right]^n = \left[ 1 - {t^2

\over 2n} + o\left({t^2 \over n}\right) \right]^n \, \rightarrow \, e^{-t^2/2}, \quad n \rightarrow \infty.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/5/1/4/5147da59182098ae4ee80d225aa23ed5.png)

![\lim_{n\to\infty} \frac{1}{s_{n}^{2+\delta}} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \mathbb{E}[|X_{i} - \mu_{i}|^{2+\delta}] = 0](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/1/e/5/1e5ca823f5b135d4ac860de3e171202e.png)