Federalist Papers

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Federalist Papers are a series of 85 articles advocating the ratification of the United States Constitution. Seventy-seven of the essays were published serially in The Independent Journal and The New York Packet between October 1787 and August 1788. A compilation of these and eight others, called The Federalist, was published in 1788 by J. and A. McLean.[1]

The Federalist Papers serve as a primary source for interpretation of the Constitution, as they outline the philosophy and motivation of the proposed system of government.[2] The authors of the Federalist Papers wanted both to influence the vote in favor of ratification and to shape future interpretations of the Constitution. According to historian Richard B. Morris, they are an "incomparable exposition of the Constitution, a classic in political science unsurpassed in both breadth and depth by the product of any later American writer."[3]

The articles were written by:

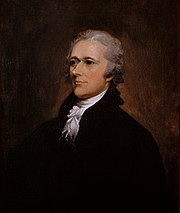

- Alexander Hamilton (51 articles: nos. 1, 6–9, 11–13, 15–17, 21–36, 59–61, and 65–85)

- James Madison (29 articles: nos. 10, 14, 18–20, 37–58, and 62–63), and

- John Jay (5 articles: 2–5 and 64).[1]

They appeared under the pseudonym "Publius," in honor of Roman consul Publius Valerius Publicola.[4] Madison is generally credited as the father of the Constitution and became the fourth President of the United States.[5] Hamilton was an active delegate at the Constitutional Convention, and became the first Secretary of the Treasury. John Jay became the first Chief Justice of the United States.

Federalist No. 10, which discusses the means of preventing faction and advocates for a large republic (and warns of the dangers of a democracy), is generally regarded as the most important of the 85 articles from a philosophical perspective.[6] Federalist No. 84 is also notable for its opposition to a Bill of Rights. Federalist No. 78 is another important one, laying down groundwork that would eventually become judicial review. Federalist No. 51 may be the clearest exposition of what has come to be called "Federalism."

Contents |

[edit] History

[edit] Origins

The states sent the Constitution for ratification in late September 1787. Immediately, the Constitution became the target of numerous articles and public letters written by Anti-Federalists and other opponents of the Constitution. For instance, the important Anti-Federalist authors "Cato" and "Brutus" debuted in New York papers on September 27 and October 18, respectively.[7] Hamilton began the Federalist Papers project as a response to the opponents of ratification, a response that would explain the new Constitution to the residents of New York and persuade them to ratify it. He wrote in Federalist No. 1 that the series would "endeavor to give a satisfactory answer to all the objections which shall have made their appearance, that may seem to have any claim to your attention."[8]

Hamilton recruited collaborators for the project. He enlisted Jay, who fell ill and was unable to contribute much to the series. Madison, present in New York as a delegate to the Congress, was recruited by Hamilton and Jay and became Hamilton's major collaborator. Gouverneur Morris and William Duer were also apparently considered; Morris turned down the invitation and Hamilton rejected three essays written by Duer.[9] Duer later wrote in support of the three Federalist authors under the name "Philo-Publius," or "Friend of Publius."

Hamilton also chose "Publius" as the pseudonym under which the series would be written. While many other pieces representing both sides of the constitutional debate were written under Roman names, Albert Furtwangler contends that "'Publius' was a cut above 'Caesar' or 'Brutus' or even 'Cato.' Publius Valerius was not a late defender of the republic but one of its founders. His more famous name, Publicola, meant 'friend of the people.'"[4] It was not the first time Hamilton had used this pseudonym: in 1778, he had applied it to three letters attacking Samuel Chase.

[edit] Publication

The Federalist Papers appeared in three New York newspapers: the Independent Journal, the New-York Packet, and the Daily Advertiser, beginning on October 27, 1787. Between them, Hamilton, Madison and Jay kept up a rapid pace, with at times three or four new essays by Publius appearing in the papers in a week. Garry Wills observes that the pace of production "overwhelmed" any possible response: "Who, given ample time could have answered such a battery of arguments? And no time was given."[10] Hamilton also encouraged the reprinting of the essay in newspapers outside New York state, and indeed they were published in several other states where the ratification debate was taking place. However, they were only irregularly published outside New York, and in other parts of the country they were often overshadowed by local writers.[11]

The high demand for the essays led to their publication in a more permanent form. On January 1, 1788, the New York publishing firm J. & A. McLean announced that they would publish the first thirty-six essays as a bound volume; that volume was released on March 2 and was titled The Federalist. New essays continued to appear in the newspapers; Federalist No. 77 was the last number to first appear in that form, on April 2. A second bound volume containing the last forty-nine essays was released on May 28. The remaining eight papers were later published in the newspapers as well.[12]

A number of later publications are worth noting. A 1792 French edition ended the collective anonymity of Publius, announcing that the work had been written by "MM Hamilton, Maddisson E Gay," citizens of the State of New York. In 1802 George Hopkins published an American edition that similarly named the authors. Hopkins wished as well that "the name of the writer should be prefixed to each number," but at this point Hamilton insisted that this was not to be, and the division of the essays between the three authors remained a secret.[13]

The first publication to divide the papers in such a way was an 1810 edition that used a list provided by Hamilton to associate the authors with their numbers; this edition appeared as two volumes of the compiled "Works of Hamilton." In 1818, Jacob Gideon published a new edition with a new listing of authors, based on a list provided by Madison. The difference between Hamilton's list and Madison's form the basis for a dispute over the authorship of a dozen of the essays.[14]

Both Hopkins's and Gideon's editions incorporated significant edits to the text of the papers themselves, generally with the approval of the authors. In 1863, Henry Dawson published an edition containing the original text of the papers, arguing that they should be preserved as they were written in that particular historical moment, not as edited by the authors years later.[15]

[edit] Disputed essays

The authorship of seventy-three of the Federalist essays is fairly certain. Twelve of these essays are disputed over by some scholars, though some newer evidence suggests James Madison as the author. The first open designation of which essay belonged to whom was provided by Hamilton, who in the days before his ultimately fatal gun duel with Aaron Burr provided his lawyer with a list detailing the author of each number. This list credited Hamilton with a full sixty-three of the essays (three of those being jointly written with Madison), almost three quarters of the whole, and was used as the basis for an 1810 printing that was the first to make specific attribution for the essays.[16]

Madison did not immediately dispute Hamilton's list, but provided his own list for the 1818 Gideon edition of The Federalist. Madison claimed twenty-nine numbers for himself, and he suggested that the difference between the two lists was "owing doubtless to the hurry in which [Hamilton's] memorandum was made out." A known error in Hamilton's list—Hamilton incorrectly ascribed No. 54 to John Jay, when in fact Jay wrote No. 64—has provided some evidence for Madison's suggestion.[17]

Statistical analysis has been undertaken on several occasions to try to decide the authorship question based on word frequencies and writing styles. Nearly all of the statistical studies show that all twelve disputed papers were written by Madison.[18][19]

[edit] Influence on the ratification debates

The Federalist Papers were written to support the ratification of the Constitution, specifically in New York. Whether they succeeded in this mission is questionable. Separate ratification proceedings took place in each state, and the essays were not reliably reprinted outside of New York; furthermore, by the time the series was well underway, a number of important states had already ratified it, for instance Pennsylvania on December 12. New York held out until July 26; certainly The Federalist was more important here than anywhere else, but Furtwangler argues that it "could hardly rival other major forces in the ratification contests"--specifically, these forces included the personal influence of well-known Federalists, for instance Hamilton and Jay, and Anti-Federalists, including Governor George Clinton.[20] Further, by the time New York came to a vote, ten states had already ratified the Constitution and it had thus already passed — only nine states had to ratify it for the new government to be established among them; the ratification by Virginia, the tenth state, placed pressure on New York to ratify. In light of that, Furtwangler observes, "New York's refusal would make that state an odd outsider."[21]

As for Virginia, which only ratified the Constitution at its convention on June 25, Hamilton writes in a letter to Madison that the collected edition of The Federalist had been sent to Virginia; Furtwangler presumes that it was to act as a "debater's handbook for the convention there," though he claims that this indirect influence would be a "dubious distinction."[22] Probably of greater importance to the Virginia debate, in any case, were George Washington's support for the proposed Constitution and the presence of Madison and Edmund Randolph, the governor, at the convention arguing for ratification.

[edit] Structure and content

In Federalist No. 1, which served as the introduction to the series, Hamilton listed six topics to be covered in the subsequent articles:

- "The utility of the UNION to your political prosperity" – covered in No. 2 through No. 14

- "The insufficiency of the present Confederation to preserve that Union"—covered in No. 15 through No. 22

- "The necessity of a government at least equally energetic with the one proposed to the attainment of this object"—covered in No. 23 through No. 36

- "The conformity of the proposed constitution to the true principles of republican government"—covered in No. 37 through No. 84

- "Its analogy to your own state constitution"—covered in No. 85

- "The additional security which its adoption will afford to the preservation of that species of government, to liberty and to prosperity"—covered in No. 85.[23]

Furtwangler notes that as the series grew, this plan was somewhat changed. The fourth topic expanded into detailed coverage of the individual articles of the Constitution and the institutions it mandated, while the two last topics were merely touched on in the last essay.

The papers can be broken down by author as well as by topic. At the start of the series, all three authors were contributing; the first twenty papers are broken down as eleven by Hamilton, five by Madison and four by Jay. The rest of the series, however, is dominated by three long segments by a single writer: No. 21 through No. 36 by Hamilton, No. 36 through 58 by Madison, written while Hamilton was in Albany, and No. 65 through the end by Hamilton, published after Madison had left for Virginia.[24]

[edit] Opposition to the Bill of Rights

The Federalist Papers (specifically Federalist No. 84) are notable for their opposition to what later became the United States Bill of Rights. The idea of adding a bill of rights to the constitution was originally controversial because the constitution, as written, did not specifically enumerate or protect the rights of the people, rather it listed the powers of the government and left all that remained to the states and the people. Alexander Hamilton, the author of Federalist No. 84, feared that such an enumeration, once written down explicitly, would later be interpreted as a list of the only rights that people had.

However, Hamilton's opposition to the Bill of Rights was far from universal. Robert Yates, writing under the pseudonym Brutus, articulated this view point in the so-called Anti-Federalist No. 84, asserting that a government unrestrained by such a bill could easily devolve into tyranny. Other supporters of the Bill argued that a list of rights would not and should not be interpreted as exhaustive; i.e., that these rights were examples of important rights that people had, but that people had other rights as well. People in this school of thought were confident that the judiciary would interpret these rights in an expansive fashion. The matter was further clarified by the Ninth Amendment.

[edit] Modern approaches and interpretations

[edit] Judicial use

Federal judges, when interpreting the Constitution, frequently use the Federalist Papers as a contemporary account of the intentions of the framers and ratifiers.[25] They have been applied on issues ranging from the power of the federal government in foreign affairs (in Hines v. Davidowitz) to the validity of ex post facto laws (in the 1798 decision Calder v. Bull, apparently the first decision to mention The Federalist).[26] As of the year 2000[update], The Federalist had been quoted 291 times in Supreme Court decisions.[27]

The amount of deference that should be given to the Federalist Papers in constitutional interpretation has always been somewhat controversial. As early as 1819, Chief Justice John Marshall noted in the famous case McCulloch v. Maryland, that "the opinions expressed by the authors of that work have been justly supposed to be entitled to great respect in expounding the Constitution. No tribute can be paid to them which exceeds their merit; but in applying their opinions to the cases which may arise in the progress of our government, a right to judge of their correctness must be retained."[28] Madison himself believed not only that The Federalist Papers were not a direct expression of the ideas of the Founders, but that those ideas themselves, and the "debates and incidental decisions of the Convention," should not be viewed as having any "authoritative character." In short, "the legitimate meaning of the Instrument must be derived from the text itself; or if a key is to be sought elsewhere, it must be not in the opinions or intentions of the Body which planned & proposed the Constitution, but in the sense attached to it by the people in their respective State Conventions where it recd. all the Authority which it possesses."[29][30]

[edit] References

- Adair, Douglass. Fame and the Founding Fathers. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1974. A collection of essays; that used here is "The Disputed Federalist Papers."

- Frederick Mosteller and David L. Wallace. Inference and Disputed Authorship: The Federalist. Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass., 1964.

- Furtwangler, Albert. The Authority of Publius: A Reading of the Federalist Papers. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1984.

- Wills, Gary. Explaining America: The Federalist, Garden City, NJ: 1981.

[edit] Notes

- ^ a b Jackson, Kenneth T. The Encyclopedia of New York City: The New York Historical Society; Yale University Press; 1995. p. 194.

- ^ Furtwangler, 17.

- ^ Richard B. Morris, The Forging of the Union: 1781-1789 (1987) p. 309

- ^ a b Furtwangler, 51.

- ^ See, e.g. Irving Brant, James Madison: Father of the Constitution, 1787-1800. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company (1950).

- ^ Wills, x.

- ^ Furtwangler, 48-49.

- ^ Gunn, Giles B. (1994). Early American Writing. Penguin Classics. pp. 540. ISBN 0140390871. http://books.google.com/books?id=OlphD37HAY4C&.

- ^ Furtwangler, 51-56.

- ^ Wills, xii.

- ^ Furtwangler, 20.

- ^ The Federalist timeline at www.sparknotes.com.

- ^ Adair, 40-41.

- ^ Adair, 44-46.

- ^ Henry Cabot Lodge, ed (1902). The Federalist, a Commentary on the Constitution of the United States. Putnam. pp. xxxviii–xliii. http://books.google.com/books?id=9S-HAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved on 2009-02-16.

- ^ Adair, 46-48.

- ^ Adair, 48.

- ^ Mosteller and Wallace.

- ^ Fung, Glenn, The disputed federalist papers: SVM feature selection via concave minimization, New York City, ACM Press, 2003. (9 pg pdf file)

- ^ Furtwangler, 21.

- ^ Furtwangler, 22.

- ^ Furtwangler, 23.

- ^ This scheme of division is adapted from Charles K. Kesler's introduction to The Federalist Papers (New York: Signet Classic, 1999) pp. 15-17. A similar division is indicated by Furtwangler, 57-58.

- ^ Wills, 274.

- ^ Lupu, Ira C.; "The Most-Cited Federalist Papers." Constitutional Commentary (1998) pp 403+; using Supreme Court citations, the five most cited were Federalist No. 42 (Madison) (33 decisions), Federalist No. 78 (Hamilton) (30 decisions), Federalist No. 81 (Hamilton) (27 decisions), Federalist No. 51 (Madison) (26 decisions), Federalist No. 32 (Hamilton) (25 decisions).

- ^ See, among others, a very early exploration of the judicial use of The Federalist in Charles W. Pierson, "The Federalist in the Supreme Court," The Yale Law Journal, Vol. 33, No. 7. (May, 1924), pp. 728-735.

- ^ Chernow, Ron. "Alexander Hamilton." Penguin Books, 2004. (p. 260)

- ^ Arthur, John (1995). Words That Bind: Judicial Review and the Grounds of Modern Constitutional Theory. Westview Press. pp. 41. ISBN 0813323495. http://books.google.com/books?id=UZu-fuHdnNwC.

- ^ Madison to Thomas Ritchie, September 15, 1821. Quoted in Furtwangler, 36.

- ^ Max Farrand, ed. (1911), The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, Yale University Press, pp. 446–447, http://books.google.com/books?id=4VQSAAAAYAAJ&dq=%22the+legitimate+meaning+of+the+Instrument+must+be+derived+from+the+text+itself%22&source=gbs_summary_s&cad=0

[edit] Further reading

- Dietze, Gottfried. The Federalist: A Classic on Federalism and Free Government, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1960.

- Epstein, David F. The Political Theory of the Federalist, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1984.

- Gray, Leslie, and Wynell Burroughs. "Teaching With Documents: Ratification of the Constitution," Social Education, 51 (1987): 322-324.

- Kesler, Charles R. Saving the Revolution: The Federalist Papers and the American Founding, New York: 1987.

- Patrick, John J., and Clair W. Keller. Lessons on the Federalist Papers: Supplements to High School Courses in American History, Government and Civics, Bloomington, IN: Organization of American Historians in association with ERIC/ChESS, 1987. ED 280 764.

- Schechter, Stephen L. Teaching about American Federal Democracy, Philadelphia: Center for the Study of Federalism at Temple University, 1984. ED 248 161.

- Sunstein, Cass R. The Enlarged Republic--Then and Now, New York Review of Books, (March 26, 2009): Volume LVI, Number 5, 45. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/22453

- Webster, Mary E. The Federalist Papers: In Modern Language Indexed for Today's Political Issues. Bellevue, WA.: Merril Press, 1999.

- White, Morton. Philosophy, The Federalist, and the Constitution, New York: 1987.

- Yarbrough, Jean. "The Federalist". This Constitution: A Bicentennial Chronicle, 16 (1987): 4-9. SO 018 489.

- Zebra Edition. The Federalist Papers: (Or, How Government is Supposed to Work), Edited for Readability. Oakesdale, WA: Lucky Zebra Press, 2007.

[edit] External links

[edit] Text of the Federalist Papers

- Fully Linkable version of The Federalist Papers

- The Avalon Project at Yale Law School: The Federalist Papers

- The Federalist Papers at the Library of Congress

- The Federalist Papers etext from Project Gutenberg

- The Federalist Papers in mp3 audio at Americana Phonic

|

||||||||||||||