Viking

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article is part of the Scandinavia series |

|---|

| Geography |

| The Viking Age |

| Political entities |

| History |

| Other |

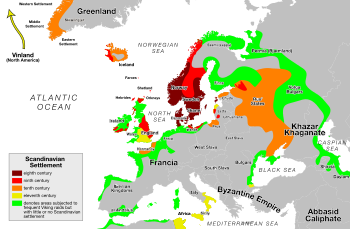

A Viking (pron. /ˈvaɪkɪŋ/) is one of the Norse (Scandinavian) explorers, warriors, merchants, and pirates who raided and colonized wide areas of Europe from the late eighth to the early eleventh century.[1] These Norsemen used their famed longships to travel as far east as Constantinople and the Volga River in Russia, and as far west as Iceland, Greenland, and Newfoundland. This period of Viking expansion is known as the Viking Age, and forms a major part of the medieval history of Scandinavia, the British Isles and Europe in general.

A romanticized picture of Vikings as Germanic noble savages emerged in the 17th century, and especially during the Victorian era Viking revival. In Britain it took the form of Septentrionalism, in Germany that of "Wagnerian" pathos or even Germanic mysticism, and in the Scandinavian countries that of Romantic nationalism or Scandinavism. In contemporary popular culture these clichéd depictions are often ironised with the effect of presenting Vikings as cartoonish characters.

Contents |

Etymology

In Old Norse, the word is spelled víkingr.[2] The word appears on several rune stones found in Scandinavia. In the Icelanders' sagas, víking refers to an overseas expedition (Old Norse fara í víking "to go on an expedition"), and víkingr, to a seaman or warrior taking part in such an expedition.

In Old English, the word wicing appears first in the Anglo-Saxon poem, "Widsith", which probably dates from the 9th century. In Old English, and in the writings of Adam von Bremen, the term refers to a pirate, and is not a name for a people or a culture in general. Regardless of its possible origins, the word was used more as a verb than as a noun, and connoted an activity and not a distinct group of individuals. To "go Viking" was distinctly different from Norse seaborne missions of trade and commerce.

The word disappeared in Middle English, and was reintroduced as Viking during 18th century Romanticism (the "Viking revival"), with heroic overtones of "barbarian warrior" or noble savage.

During the 20th century, the meaning of the term was expanded to refer not only to the raiders, but also to the entire period; it is now, somewhat confusingly, used as a noun both in the original meaning of raiders, warriors or navigators, and to refer to the Scandinavian population in general. As an adjective, the word is used in expressions like "Viking age", "Viking culture", "Viking colony", etc., generally referring to medieval Scandinavia. The pre-Christian Scandinavian population is also referred to as Norse, although that term is properly applied to the whole civilization of Old-Norse-speaking people. In current Scandinavian languages, the term Viking is applied to the people who went away on Viking expeditions, be it for raiding or trading.[3]

The term Varangians made its first appearance in Byzantium where it was introduced to designate a function. In Russia it was extended to apply to Scandinavian warriors journeying to and from Constantinople. In the Byzantine sources Varangians are first mentioned in 1034 as in garrison in the Thracian theme. The Arabic geographer Al Biruni has mentioned the Baltic Sea as the Varangian Sea and specifies the Varangians as a people dwelling on its coasts. The first datable use of the word in Norse literature appears by Einarr Skúlason in 1153. According to Icelandic Njalssaga from the 13th century, the institution of Varangian Guard was established by 1000. In the Russian Primary Chronicle the Varangian is used as a generic term for the Germanic nations on the coasts of the Baltic sea that likewise lived in the west as far as the land of the English and the French.[4]

The word Væringjar itself is regarded in Scandinavia as of Old Norse origin, cognate with the Old English Færgenga (literally, an expedition-goer).

The Viking Age

The period from the earliest recorded raids in the 790s until the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 is commonly known as the Viking Age of Scandinavian history. The Normans, however, were descended from Danish Vikings who were given feudal overlordship of areas in northern France — the Duchy of Normandy — in the 8th century. In that respect, descendants of the Vikings continued to have an influence in northern Europe. Likewise, King Harold Godwinson, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England who was killed during the Norman invasion in 1066, had Danish ancestors. Many of the medieval kings of Norway and Denmark married into English and Scottish royalty and occasionally got involved in dynastic disputes.[citation needed]

Geographically, a "Viking Age" may be assigned not only to Scandinavian lands (modern Denmark, Norway and Sweden), but also to territories under North Germanic dominance, mainly the Danelaw, formerly the Kingdom of Northumbria, parts of Mercia, and East Anglia.[citation needed] Viking navigators opened the road to new lands to the north, west and east, resulting in the foundation of independent settlements in the Shetland, Orkney, and Faroe Islands; Iceland; Greenland;[5] and L'Anse aux Meadows, a short-lived settlement in Newfoundland, circa 1000 A.D.[6] Many of these lands, specifically Greenland and Iceland, may have been originally discovered by sailors blown off course.[citation needed] They also may well have been deliberately sought out, perhaps on the basis of the accounts of sailors who had seen land in the distance. The Greenland settlement eventually died out, possibly due to climate change. Vikings also explored and settled in territories in Slavic-dominated areas of Eastern Europe. By 950 AD these settlements were largely Slavicized.

From 839, Varangian mercenaries in the service of the Byzantine Empire, notably Harald Hardrada, campaigned in North Africa, Jerusalem, and other places in the Middle East. Important trading ports during the period include Birka, Hedeby, Kaupang, Jorvik, Staraya Ladoga, Novgorod and Kiev.

There is archaeological evidence that Vikings reached the city of Baghdad, the center of the Islamic Empire.[7] The Norse regularly plied the Volga with their trade goods: furs, tusks, seal fat for boat sealant and slaves. However, they were far less successful in establishing settlements in the Middle East, due to the more centralized Islamic power.[citation needed]

Generally speaking, the Norwegians expanded to the north and west to places such as Ireland, Iceland and Greenland; the Danes to England and France, settling in the Danelaw (northern/eastern England) and Normandy; and the Swedes to the east. These nations, although distinct, were similar in culture and language. The names of Scandinavian kings are known only for the later part of the Viking Age. Only after the end of the Viking Age did the separate kingdoms acquire distinct identities as nations, which went hand in hand with their Christianization. Thus the end of the Viking Age for the Scandinavians also marks the start of their relatively brief Middle Ages.

Viking expansion

The Vikings sailed most of the North Atlantic, reaching south to North Africa and east to Russia, Constantinople and the middle east, as looters, traders, colonists, and mercenaries. Vikings under Leif Eriksson, heir to Erik the Red, reached North America, and set up a short-lived settlement in present-day L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada.

The motives driving the Viking expansion form a topic of much debate in Nordic history. One common theory posits that the Norse population had outgrown agricultural potential of their Scandinavian homeland.[citation needed] For a coastal population with superior naval technologies, it made sense to expand overseas in the face of a youth bulge effect. However, this theory does little to explain why the expansion went overseas rather than into the vast, uncultivated forest areas on the interior of the Scandinavian Peninsula. It should be noted that sea raiding was easier than clearing large areas of forest for farm and pasture in a region with a limited growing season. No such rise in population or decline in agricultural production has been definitively proven.

Another explanation is that the Vikings exploited a moment of weakness in the surrounding regions. For instance, the Danish Vikings were aware of the internal divisions within Charlemagne's empire that began in the 830s and resulted in schism.[citation needed] England suffered from internal divisions, and was relatively easy prey given the proximity of many towns to the sea or navigable rivers. Lack of organized naval opposition throughout Western Europe allowed Viking ships to travel freely, raiding or trading as opportunity permitted.

The decline in the profitability of old trade routes could also have played a role. Trade between western Europe and the rest of Eurasia suffered a severe blow when the Roman Empire fell in the 5th century.[citation needed] The expansion of Islam in the 7th century had also affected trade with western Europe.[citation needed] Trade on the Mediterranean Sea was historically at its lowest level when the Vikings initiated their expansion.[citation needed] By opening new trade routes in Arabic and Frankish lands, the Vikings profited from international trade by expanding beyond their traditional boundaries.[citation needed] Finally, the destruction of the Frisian fleet by the Franks afforded the Vikings an opportunity to take over their trade markets.[citation needed]

Decline

Following a period of thriving trade and Viking settlement, cultural impulses flowed from the rest of Europe to affect Viking dominance. Christianity had an early and growing presence in Scandinavia, and with the rise of centralized authority and the development of more robust coastal defense systems, Viking raids became more risky and less profitable.

Snorri Sturluson in the saga of St. Olafr chapter 73, describes the brutal process of Christianisation in Norway: “…those who did not give up paganism were banished, with others he (St. Olafr) cut off their hands or their feet or extirpated their eyes, others he ordered hanged or decapitated, but did not leave unpunished any of those who did not want to serve God (…) he afflicted them with great punishments (…) He gave them clerks and instituted some in the districts.”

As the new quasi-feudalistic system became entrenched in Scandinavian rule, organized opposition sealed the Vikings' fate. Eleventh-century chronicles note Scandinavian attempts to combat the Vikings from the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea, which eventually led to Danish and Swedish participation in the Baltic Crusades during the 12th and 13th centuries. It also contributed to the development of the Hanseatic League.[8]

One of the primary profit centers of Viking trade was slavery. The Church took a position that Christians should not own fellow Christians as slaves, so chattel slavery diminished as a practice throughout Northern Europe. Eventually, outright slavery was outlawed, replaced with serfdom at the bottom rung of Medieval society. This took much of the economic incentive out of raiding, though sporadic activity continued for a few decades beyond the Norman conquest of England.

Weapons and warfare

Our knowledge about arms and armor of the Viking age is based on relatively sparse archaeological finds, pictorial representation, and to some extent on the accounts in the Norse sagas and Norse laws recorded in the 13th century.

According to custom, all free Norse men were required to own weapons, as well as permitted to carry them at all times. These arms were also indicative of a Viking's social status: a wealthy Viking would have a complete ensemble of a helmet, shield, chainmail shirt, and sword. A typical bóndi (freeman) was more likely to fight with a spear and shield, and most also carried a seax as a utility knife and side-arm. Bows were used in the opening stages of land battles, and at sea, but tended to be considered less "honorable" than a hand weapon. Vikings were relatively unique for the time in their use of axes as a main battle weapon. The Húscarls, the elite guard of King Cnut (and later King Harold II) were armed with two-handed axes which could split shields or metal helmets with ease.

Archaeology

| It has been suggested that this section be split into a new article. (Discuss) |

With a distinct lack of totally reliable written sources on the topic, much of the historical investigation of the Viking period relies on archaeology.[9]

Runestones

The vast majority of runic inscriptions from the Viking period come from Sweden, especially from the tenth and eleventh century. Many runestones in Scandinavia record the names of participants in Viking expeditions, such as the Kjula Runestone which tells of extensive warfare in Western Europe and the Turinge Runestone which tells of a warband in Eastern Europe. Other runestones mention men who died on Viking expeditions, among them the around 25 Ingvar Runestones in the Mälardalen district of Sweden erected to commemorate members of a disastrous expedition into present-day Russia in the early 11th century. The runestones are important sources in the study of Norse society and early medieval Scandinavia, not only of the 'Viking' segment of the population (Sawyer, P H: 1997).

Runestones attest to voyages to locations, such as Bath,[10] Greece,[11] Khwaresm,[12] Jerusalem,[13] Italy (as Langobardland),[14] London,[15] Serkland (i.e. the Muslim world),[16] England,[17] and various locations in Eastern Europe.

The word Viking appears on several runestones found in Scandinavia.

Burial sites

There are numerous burial sites associated with Vikings. As well as providing information on Viking religion, burial sites also provide information on social structure. The items buried with the deceased give some indication as to what was considered important to possess in the afterlife.[18] Some examples of notable burial sites include:

- Gettlinge gravfält, Öland, Sweden, ship outline

- Jelling, Denmark, a World Heritage Site

- Oseberg, Norway.

- Gokstad, Norway.

- Borrehaugene, Horten, Norway

- Tuna, Sweden.

- Gamla Uppsala, Sweden.

- Hulterstad gravfält, near the villages of Alby and Hulterstad, Öland, Sweden, ship outline of standing stones

Ships

There were two distinct classes of Viking ships: the longship (sometimes erroneously called "drakkar", a corruption of "dragon" in Norse) and the knarr. The longship, intended for warfare and exploration, was designed for speed and agility, and were equipped with oars to complement the sail as well as making it able to navigate independently of the wind. The longship had a long and narrow hull, as well as a shallow draft, in order to facilitate landings and troop deployments in shallow water. The knarr was a dedicated merchant vessel designed to carry cargo. It was designed with a broader hull, deeper draft and limited number of oars (used primarily to maneuver in harbors and similar situations). One Viking innovation was the beitass, a spar mounted to the sail that allowed their ships to sail effectively against the wind.[19]

Longships were used extensively by the Leidang, the Scandinavian defense fleets. The term "Viking ships" has entered common usage, however, possibly because of its romantic associations (discussed below).

In Roskilde are the well-preserved remains of five ships, excavated from nearby Roskilde Fjord in the late 1960s. The ships were scuttled there in the 11th century to block a navigation channel, thus protecting the city, which was then the Danish capital, from seaborne assault. These five ships represent the two distinct classes of Viking ships, the longship and the knarr. The remains of these ships can be found on display at the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde.

Longships are not to be confused with later-period longboats. It was common for Viking ships to tow or carry a smaller boat to transfer crews and cargo from the ship to shore, however.

Genetic legacy

Studies of genetic diversity provide some indication of the origin and expansion of the Viking population. The Haplogroup I1 (defined by specific genetic markers on the Y-chomosome) is sometimes referred to as the "Viking haplogroup". This mutation occurs with the greatest frequency among Scandinavian males: 35 percent in Norway, Denmark and Sweden, and peaking at 40 percent within western Finland. [20] It is also common near the southern Baltic and North Sea coasts, and then successively decreases the further south geographically.

Genetic studies in England have demonstrated that the Vikings settled in the British Isles as well as raiding there. Both male and female descent studies show evidence of Norwegian descent in areas closest to Scandinavia, such as the Shetland and Orkney Islands. Inhabitants of lands further away show most Norse descent in the male Y chromosome lines.[21]

A specialized surname study in Liverpool demonstrated marked Norse heritage, up to 50 percent of males who belonged to original families, those who lived there before the years of industrialization and population expansion. High percentages of Norse inheritance were also found among males in Wirral and West Lancashire. This was similar to the percentage of Norse inheritance found among males in the Orkney Islands. [22]

Historical opinion and cultural legacy

In England the Viking Age began dramatically on 8 June 793 when Norsemen destroyed the abbey on the island of Lindisfarne. The devastation of Northumbria's Holy Island shocked and alerted the royal Courts of Europe to the Viking presence. "Never before has such an atrocity been seen," declared the Northumbrian scholar, Alcuin of York.[citation needed] More than any other single event, the attack on Lindisfarne demonized perception of the Vikings for the next twelve centuries. Not until the 1890s did scholars outside Scandinavia begin to seriously reassess the achievements of the Vikings, recognizing their artistry, technological skills and seamanship.[23]

The first challenges to anti-Viking sentiments in Britain emerged in the 17th century. Pioneering scholarly editions of the Viking Age began to reach a small readership in Britain, archaeologists began to dig up Britain's Viking past, and linguistic enthusiasts started to identify the Viking-Age origins for rural idioms and proverbs. The new dictionaries of the Old Norse language enabled the Victorians to grapple with the primary Icelandic sagas.[24]

In Scandinavia, the 17th century Danish scholars Thomas Bartholin and Ole Worm, and Olof Rudbeck of Sweden were the first to set the standard for using runic inscriptions and Icelandic Sagas as historical sources.[citation needed] During the Age of Enlightenment and the Nordic Renaissance, historical scholarship in Scandinavia became more rational and pragmatic, as witnessed by the works of a Danish historian Ludvig Holberg and Swedish historian Olof von Dalin.[citation needed] Until recently, the history of the Viking Age was largely based on Icelandic sagas, the history of the Danes written by Saxo Grammaticus, the Russian Primary Chronicle and the The War of the Irish with the Foreigners. Although few scholars still accept these texts as reliable sources, historians nowadays rely more on archeology and numismatics, disciplines that have made valuable contributions toward understanding the period.[25]

Until the 19th century reign of Queen Victoria, public perceptions in Britain continued to portray Vikings as violent and bloodthirsty.[citation needed] The chronicles of medieval England had always portrayed them as rapacious 'wolves among sheep'.[citation needed] In 1920, a winged-helmeted Viking was introduced as a radiator cap figure on the new Rover car, marking the start of the cultural rehabilitation of the Vikings in Britain.[citation needed]

Icelandic sagas and other texts

Norse mythology, sagas and literature tell of Scandinavian culture and religion through tales of heroic and mythological heroes. However, early transmission of this information was primarily oral, and later texts were reliant upon the writings and transcriptions of Christian scholars, including the Icelanders Snorri Sturluson and Sæmundur fróði. Many of these sagas were written in Iceland, and most of them, even if they had no Icelandic provenance, were preserved there after the Middle Ages due to the Icelanders' continued interest in Norse literature and law codes.

The 200-year Viking influence on European history is filled with tales of plunder and colonization, and the majority of these chronicles came from western witnesses and their descendants. Less common, though equally relevant, are the Viking chronicles that originated in the east, including the Nestor chronicles, Novgorod chronicles, Ibn Fadlan chronicles, Ibn Ruslan chronicles, and many brief mentions by the Fosio bishop from the first big attack on the Byzantine Empire.

Other chroniclers of Viking history include Adam of Bremen, who wrote "There is much gold here (in Zealand), accumulated by piracy. These pirates, which are called wichingi by their own people, and Ascomanni by our own people, pay tribute to the Danish king" in the fourth volume of his Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum.

In 991, the Battle of Maldon between Viking raiders and the inhabitants of the town of Maldon in Essex, England was commemorated with a poem of the same name.

Modern revivals

Early modern publications, dealing with what we now call Viking culture, appeared in the 16th century, e.g. Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (Olaus Magnus, 1555), and the first edition of the 13th century Gesta Danorum of Saxo Grammaticus in 1514. The pace of publication increased during the 17th century with Latin translations of the Edda (notably Peder Resen's Edda Islandorum of 1665).

The word Viking was popularized, with positive connotations, by Erik Gustaf Geijer in the poem, The Viking, written at the beginning of the 19th century. The word was taken to refer to romanticized, idealized naval warriors, who had very little to do with the historical Viking culture. This renewed interest of Romanticism in the Old North had political implications. A myth about a glorious and brave past was needed to give the Swedes the courage to retake Finland, which had been lost in 1809 during the war between Sweden and Russia. The Geatish Society, of which Geijer was a member, popularized this myth to a great extent. Another Swedish author who had great influence on the perception of the Vikings was Esaias Tegnér, member of the Geatish Society, who wrote a modern version of Friðþjófs saga ins frœkna, which became widely popular in the Nordic countries, the United Kingdom and Germany.

A focus for early British enthusiasts was George Hicke, who published a Linguarum vett. septentrionalium thesaurus in 1703 – 05. During the 18th century, British interest and enthusiasm for Iceland and Nordic culture grew dramatically, expressed in English translations as well as original poems, extolling Viking virtues and increased interest in anything Runic that could be found in the Danelaw, rising to a peak during Victorian times.

Nazi and fascist imagery

Political organizations of the same tradition, such as the former Norwegian nationalist/fascist party, Nasjonal Samling, used an amount of Viking symbolism combined with Roman symbolism and imagery widely in their propaganda and aesthetical approach.

Similar to Wagnerian mythology, the romanticism of the heroic Viking ideal appealed to the Germanic supremacist thinkers of Nazi Germany. Political organizations of the same tradition, such as the former Norwegian nationalist/fascist party, Nasjonal Samling, used Viking symbolism and imagery widely in its propaganda. The Viking legacy had an impact in parts of Europe, especially the Northern Baltic region, but in no way was the Viking experience particular to Germany. However, the Nazis did not claim themselves to be the descendants of any Viking settlers. Instead, they resorted to the historical and ethnic fact that the Vikings were descendants of other Germanic peoples; this fact is supported by the shared ethnic-genetic elements, and cultural and linguistic traits, of the Germans, Anglo-Saxons, and Viking Scandinavians. In particular, all these peoples also had traditions of Germanic paganism and practiced runelore. This common Germanic identity became - and still is - the foundation for much National Socialist iconography. For example, the runic emblem of the SS utilized the sig rune of the Elder Futhark and the youth organization Wiking-Jugend made extensive use of the odal rune. This trend still holds true today (see also fascist symbolism).

Reenactment

Since the 1960s, there has been rising enthusiasm for historical reenactment. While the earliest groups had little claim for historical accuracy, the seriousness and accuracy of re-enactors has increased. The largest such groups include The Vikings and Regia Anglorum, though many smaller groups exist in Europe, the UK, North America, New Zealand, and Australia. Many reenactor groups participate in live-steel combat, and a few have Viking-style ships or boats.

On 1 July 2007, the reconstructed Viking ship Skuldelev 2, renamed Sea Stallion,[26] began a journey from Roskilde, Denmark to Dublin, Ireland. The remains of that ship and four others were discovered during a 1962 excavation in the Roskilde Fjord. This multi-national experimental archeology project saw 70 crew members sail the ship back to its home in Ireland. Tests of the original wood show that it was made of Irish trees. The Sea Stallion arrived outside Dublin's Custom House on 14 August 2007.

The purpose of the voyage was to test and document the seaworthiness, speed and maneuverability of the ship on the rough open sea and in coastal waters with treacherous currents. The crew tested how the long, narrow, flexible hull withstood the tough ocean waves. The expedition also provided valuable new information on Viking longships and society. The ship was built using Viking tools, materials and much the same methods as the original ship.

In fiction

Led by the operas of German composer Richard Wagner, such as Der Ring des Nibelungen, Vikings and the Romanticist Viking Revival inspired many creative works.

These included novels directly based on historical events, such as Frans Gunnar Bengtsson's The Long Ships (which was also released as a 1963 film), and historical fantasies such as the film The Vikings, Michael Crichton's Eaters of the Dead (movie version called The 13th Warrior) and the comedy film Erik the Viking. Vikings appear in several books by the Danish American writer Poul Anderson.

The genre of Viking metal shows persisting modern influence of the Viking myths. It was a popular sub-genre of heavy metal music, originating in the early 1990s as an off-shoot of the black metal sub-genre.

This style is notable for its lyrical and theatrical emphasis on Norse mythology as well as Viking lifestyles and beliefs. Popular bands that contribute to this genre include Turisas, Amon Amarth, Einherjer, Valhalla, Týr, Ensiferum, Falkenbach, and Enslaved.

Common misconceptions

Horned helmets

Apart from two or three representations of (ritual) helmets – with protrusions that may be either stylized ravens, snakes or horns – no depiction of Viking Age warriors' helmets, and no preserved helmet, has horns. In fact, the formal close-quarters style of Viking combat (either in shield walls or aboard "ship islands") would have made horned helmets cumbersome and hazardous to the warrior's own side.

Therefore historians believe that Viking warriors did not use horned helmets, but whether or not such helmets were used in Scandinavian culture for other, ritual purposes remains unproven. The general misconception that Viking warriors wore horned helmets was partly promulgated by the 19th century enthusiasts of Götiska Förbundet, founded in 1811 in Stockholm, Sweden. They promoted the use of Norse mythology as the subject of high art and other ethnological and moral aims.

The Vikings were often depicted with winged helmets and in other clothing taken from Classical antiquity, especially in depictions of Norse gods. This was done in order to legitimize the Vikings and their mythology by associating it with the Classical world which had long been idealized in European culture.

The latter-day mythos created by national romantic ideas blended the Viking Age with aspects of the Nordic Bronze Age some 2,000 years earlier. Horned helmets from the Bronze Age were shown in petroglyphs and appeared in archaeological finds (see Bohuslän and Vikso helmets). They were probably used for ceremonial purposes. [27]).

Cartoons like Hägar the Horrible and Vicky the Viking, and sports uniforms such as those of the Minnesota Vikings and Canberra Raiders football teams have perpetuated the mythic cliché of the horned helmet.

Viking helmets were conical, made from hard leather with wood and metallic reinforcement for regular troops. The iron helmet with mask and chain mail was for the chieftains, based on the previous Vendel-age helmets from central Sweden. The only true Viking helmet found is that from Gjermundbu in Norway. This helmet is made of iron and has been dated to the 10th century.

Skull cups

The use of human skulls as drinking vessels is also ahistorical. The rise of this legend can be traced to Ole Worm's Runer seu Danica literatura antiquissima (1636), in which Danish warriors drinking ór bjúgviðum hausa [from the curved branches of skulls, i.e. from horns] were rendered as drinking ex craniis eorum quos ceciderunt [from the skulls of those whom they had slain]. The skull-cup allegation may also have some history in relation with other Germanic tribes and Eurasian nomads, such as the Scythians and Pechenegs, and the vivid example of the Lombard Alboin, made notorious by Paul the Deacon's History.

Uncleanliness

The image of wild-haired, dirty savages sometimes associated with the Vikings in popular culture[who?] is a distorted picture of reality.[1] Non-Scandinavian Christians are responsible for most surviving accounts of the Vikings and, consequently, a strong possibility for bias exists. This attitude is likely attributed to Christian misunderstandings regarding paganism. Viking tendencies were often misreported and the work of Adam of Bremen, among others, told largely disputable tales of Viking savagery and uncleanliness.[28]

However, it is now known that the Vikings used a variety of tools for personal grooming such as combs, tweezers, razors or specialized "ear spoons". In particular, combs are among the most frequent artifacts from Viking Age excavations. The Vikings also made soap, which they used to bleach their hair as well as for cleaning, as blonde hair was ideal in the Viking culture.

The Vikings in England even had a particular reputation for excessive cleanliness, due to their custom of bathing once a week, on Saturdays (unlike the local Anglo-Saxons). To this day, Saturday is referred to as laugardagur / laurdag / lørdag / lördag, "washing day" in the Scandinavian languages, though the original meaning is lost in modern speech in most of the Scandinavian languages ("laug" still means "bath" or "pool" in Icelandic).

As for the Vikings in the east, Ibn Rustah explicitly notes their cleanliness, while Ibn Fadlan is disgusted by all of the men sharing the same, used vessel to wash their faces and blow their noses in the morning. Ibn Fadlan's disgust is probably motivated by his ideas of personal hygiene particular to the Muslim world, such as running water and clean vessels. While the example intended to convey his disgust about the customs of the Rus', at the same time it recorded that they did wash every morning.

Vikings of renown

- Askold and Dir, legendary Varangian conquerors of Kiev.

- Björn Ironside, son of Ragnar Lodbrok, pillaged in Italy.

- Brodir of Man, a Danish Viking who killed the High King of Ireland, Brian Boru.

- Canute the Great, king of England and Denmark, Norway, and of some of Sweden, was possibly the greatest Viking king. A son of Sweyn Forkbeard, and grandson of Harold Bluetooth, he was a member of the dynasty that was key to the unification and Christianisation of Denmark. Some modern historians have dubbed him the ‘Emperor of the North’ because of his position as one of the magnates of medieval Europe and as a reflection of the Holy Roman Empire to the south.

- Egill Skallagrímsson, Icelandic warrior and skald. (See also Egils saga).

- Eric the Victorious, a king of Sweden whose dynasty is the first known to have ruled as kings of the nation. It is possible he was king of Denmark for a time.

- Erik the Red, colonizer of Greenland.

- Freydís Eiríksdóttir, a Viking woman who sailed to Vínland.

- Gardar Svavarsson, originally from Sweden, the discoverer of Iceland. There is another contender for the discoverer of Iceland: Naddoddr, a Norwegian/Faeroese Viking explorer.

- Godfrid, Duke of Frisia, a pillager of the Low Countries and the Rhine area and briefly a lord of Frisia.

- Godfrid Haraldsson, son of Harald Klak and pillager of the Low Countries and northern France.

- Grímur Kamban, a Norwegian or Norwegian/Irish Viking who around 825 was, according to the Færeyinga Saga, the first Nordic settler in the Faeroes.

- Guthrum, colonizer of Danelaw.

- Harald Klak (Harald Halfdansson), a 9th c. king in Jutland who made peace with Louis the Pious and was possibly the first Viking to be granted Frankish land in exchange for protection.

- Harald Bluetooth (Harald Gormson), who according to the Jelling Stones that he had erected, "won the whole of Denmark and Norway and turned the Danes to Christianity". Father of Sweyn Forkbeard; grandfather of Canute the Great.

- Harald Hardrada, a Norwegian king who died, along with his men, at Stamford Bridge in an unsuccessful attempt to conquer England in 1066. Only a fraction of the invasion force is thought to have made their escape.

- Hastein, a chieftain who raided in the Mediterranean.

- Ingólfur Arnarson, colonizer of Iceland.

- Ingvar the Far-Travelled, the leader of the last great Swedish Viking expedition to pillage the shores of the Caspian Sea.

- Ivar the Boneless, the disabled Viking who conquered York, despite having to be carried on a shield. Son of Ragnar Lodbrok.

- Leif Ericsson, discoverer of Vínland, son of Erik the Red.

- Naddoddr, a Norwegian/Faeroese Viking explorer.

- Olaf Tryggvason, king of Norway from 995 to 1000. He forced thousands to convert to Christianity. He once burned London Bridge down out of anger because people were disobeying his orders (and this is conjectured to be origin of the children's rhyme "London Bridge is Falling Down").

- St Olaf (Olav Haraldsson), patron saint of Norway, and king of Norway from 1015 to approx. 1030.

- Oleg of Kiev, led an offensive against Constantinople.

- Ragnar Lodbrok, captured Paris.

- Rollo of Normandy, founder of Normandy.

- Rorik of Dorestad, a Viking lord of Frisia and nephew of Harald Klak.

- Rurik, founder of the Rus' rule in Eastern Europe.

- Sigmundur Brestisson, Faeroese, a Viking chieftain who, according to the Færeyinga Saga, introduced Christianity and Norwegian supremacy to the Faeroes in 999.

- Sweyn Forkbeard, king of Denmark, Norway, and England, as well as founder of Swansea ("Sweyn's island"). In 1013, the Danes under Sweyn led a Viking offensive against the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of England. The English king was forced into exile, and in late 1013 Sweyn became King of England, though he died early in 1014, and the former king was brought out of exile to challenge his son.

- Thorgils (Thorgest), founder of Dublin.

- Tróndur í Gøtu, a Faeroese Viking chieftain who, according to the Færeyinga Saga, was opposed to the introduction of Christianity to, and the Norwegian supremacy of, the Faeroes.

- William the Conqueror, ruler of Normandy and the victor at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. His kingship of England saw the end of the Anglo-Saxon era and the encroachment of continental magnates and the ideals of Christendom. His great great uncle was Canute the Great.

Notes

- ^ a b Roesdahl, p. 9-22.

- ^ The Syntax of Old Norse By Jan Terje Faarlund; p 25 ISBN 0199271100; The Principles of English Etymology By Walter W. Skeat, published in 1892, defined Viking: better Wiking, Icel. Viking-r, O. Icel. *Viking-r, a creek-dweller; from Icel. vik, O. Icel. *wik, a creek, bay, with suffix -uig-r, belonging to Principles of English Etymology By Walter W. Skeat; Clarendon press; Page 479

- ^ See Gunnar Karlsson, "Er rökrétt að fullyrða að landnámsmenn á Íslandi hafi verið víkingar?", The University of Iceland Science web April 30, 2007; Gunnar Karlsson, "Hver voru helstu vopn víkinga og hvernig voru þau gerð? Voru þeir mjög bardagaglaðir?", The University of Iceland Science web December 20, 2006; and Sverrir Jakobsson "Hvaðan komu víkingarnir og hvaða áhrif höfðu þeir í öðrum löndum?", The University of Iceland Science web July 13, 2001 (in Icelandic).

- ^ The Russian Primary Chronicle: Laurentian Text Translated by O. P

- ^ The Fate of Greenland's Vikings, by Dale Mackenzie Brown, Archaeological Institute of America, February 28, 2000

- ^ The Norse discovery of America

- ^ Vikings' Barbaric Bad Rap Beginning to Fade

- ^ The Northern Crusades: Second Edition by Eric Christiansen; p.93; ISBN 0140266534

- ^ Roesdahl, p. 16-22.

- ^ baþum (Sm101), see Nordiskt runnamnslexikon PDF

- ^ In the nominative: krikiaR (G216). In the genitive: girkha (U922$), k--ika (U104). In the dative: girkium (U1087†), kirikium (SöFv1954;20, U73, U140), ki(r)k(i)(u)(m) (Ög94$), kirkum (U136), krikium (Sö163, U431), krikum (Ög81A, Ög81B, Sö85, Sö165, Vg178, U201, U518), kri(k)um (U792), krikum (Sm46†, U446†), krkum (U358), kr... (Sö345$A), kRkum (Sö82). In the accusative: kriki (Sö170). Uncertain case krik (U1016$Q). Greece also appears as griklanti (U112B), kriklati (U540), kriklontr (U374$), see Nordiskt runnamnslexikon PDF

- ^ Karusm (Vs1), see Nordiskt runnamnslexikon PDF

- ^ iaursaliR (G216), iursala (U605†), iursalir (U136G216, U605, U136), see Nordiskt runnamnslexikon PDF

- ^ lakbarþilanti (SöFv1954;22), see Nordiskt runnamnslexikon PDF

- ^ luntunum (DR337$B), see Nordiskt runnamnslexikon PDF

- ^ serklat (G216), se(r)kl... (Sö279), sirklanti (Sö131), sirk:lan:ti (Sö179), sirk*la(t)... (Sö281), srklant- (U785), skalat- (U439), see Nordiskt runnamnslexikon PDF

- ^ eklans (Vs18$), eklans (Sö83†), ekla-s (Vs5), enklans (Sö55), iklans (Sö207), iklanþs (U539C), ailati (Ög104), aklati (Sö166), akla-- (U616$), anklanti (U194), eg×loti (U812), eklanti (Sö46, Sm27), eklati (ÖgFv1950;341, Sm5C, Vs9), enklanti (DR6C), haklati (Sm101), iklanti (Vg20), iklati (Sm77), ikla-ti (Gs8), i...-ti (Sm104), ok*lanti (Vg187), oklati (Sö160), onklanti (U241), onklati (U344), -klanti (Sm29$), iklot (N184), see Nordiskt runnamnslexikon PDF

- ^ Roesdahl, p. 20.

- ^ Block, Leo, To Harness the Wind: A Short History of the Development of Sails, Naval Institute Press, 2002, ISBN 1557502099

- ^ Map of I1a

- ^ Roger Highfield, "Vikings who chose a home in Shetland before a life of pillage", Telegraph, 7 Apr 2005, accessed 16 Nov 2008

- ^ James Randerson, "Proof of Liverpool's Viking past", The Guardian, 3 Dec 2007, accessed 16 Nov 2008

- ^ Northern Shores by Alan Palmer; p.21; ISBN 0719562996

- ^ The Viking Revival By Professor Andrew Wawn at bbc

- ^ The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings By Peter Hayes SawyerISBN 0198205260

- ^ Return of Dublin's Viking Warship. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ Did Vikings really wear horns on their helmets?, The Straight Dope, 7 December 2004. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ Williams, G. (2001) How do we know about the Vikings? BBC.co.uk. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

References

- Downham, Clare, Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland: The Dynasty of Ívarr to AD 1014. Dunedin Academic Press, 2007. ISBN 1903765890

- Hadley, D.M., The Vikings in England: Settlement, Society and Culture. Manchester University Press, 2006. ISBN 0719059828

- Hall, Richard, Exploring the World of the Vikings. Thames and Hudson, 2007. ISBN 9780500051443

- Roesdahl, Else. The Vikings. Penguin, 1998. ISBN 0140252827

- Sawyer, Peter, The Age of the Vikings (second edition) Palgrave Macmillan, 1972. ISBN 0312013655

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Viking Age |

External links

- BBC: History of Vikings

- Encyclopedia Britannica: Viking, or Norseman, or Northman, or Varangian (people)

- Borg Viking museum, Norway

- Ibn Fadlan and the Rusiyyah, by James E. Montgomery, with full translation of Ibn Fadlan

- Reassessing what we collect website – Viking and Danish London History of Viking and Danish London with objects and images

- The Viking Answer Lady Webpage

- The Viking Rune: All Things Norse and Germanic