Berlin Wall

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- For the chess position, see Ruy Lopez#Berlin Defence.

The Berlin Wall (German: Berliner Mauer) was a physical barrier separating West Berlin from the German Democratic Republic (GDR) (East Germany), including East Berlin. The longer inner German border demarcated the border between East and West Germany. Both borders came to symbolize the Iron Curtain between Western Europe and the Eastern Bloc.

The wall separated East Germany from West Germany for more than a quarter-century, from the day construction began on 13 August 1961 until the Wall was opened on 9 November 1989.[1] During this period, at least 98 people were confirmed killed trying to cross the Wall into West Berlin, according to official figures. However, a prominent victims' group claims that more than 200 people were killed trying to flee from East to West Berlin.[2] The East German government issued shooting orders to border guards dealing with defectors, though such orders are not the same as shoot to kill orders which GDR officials denied ever issuing.[3]

When the East German government announced on 9 November 1989, after several weeks of civil unrest, that all GDR citizens could visit West Germany and West Berlin, crowds of East Germans climbed onto and crossed the wall, joined by West Germans on the other side in a celebratory atmosphere. Over the next few weeks, parts of the wall were chipped away by a euphoric public and by souvenir hunters; industrial equipment was later used to remove almost all of the rest of it.

The fall of the Berlin Wall paved the way for German reunification, which was formally concluded on 3 October 1990.

Contents |

[edit] Background

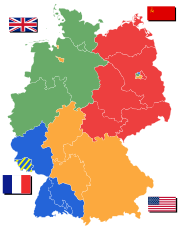

After the end of World War II in Europe, what remained of Nazi Germany west of the Oder-Neisse line was divided into four occupation zones (per the Potsdam Agreement), each one controlled by one of the four occupying Allied powers: the Americans, British, French and Soviets. The capital, Berlin, as the seat of the Allied Control Council, was similarly subdivided into four sectors despite the city lying deep inside the Soviet zone. Although the occupying powers originally intended to jointly govern Germany within its postwar borders, the advent of Cold War tensions caused the French, British and American zones to be formed into the Federal Republic of Germany (and West Berlin) in 1949, excluding the Soviet zone, which then formed the German Democratic Republic (including East Berlin).

[edit] Divergence of the two German states

West Germany, known in German as the Bundesrepublik Deutschlandor" FRG (Federal Republic of Germany), developed into a Western capitalist country with a social market economy ("Soziale Marktwirtschaft" in German) and a democratic parliamentary government. Continual economic growth starting in the 1950s fuelled a 20-year "economic miracle" ("Wirtschaftswunder"). Across the inner-German border, East Germany, known in Germany as the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (German Democratic Republic), established an authoritarian government with a Soviet-style planned economy. As West Germany's economy grew and its standard of living continually improved, many East Germans wanted to move to West Germany.

[edit] Emigration westward in the early 1950s

After Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe at the end of World War II, the majority of those living in the newly acquired areas of the Eastern Bloc aspired to independence and wanted the Soviets to leave.[4] Taking advantage of the zonal border between occupied zones in Germany, the number of GDR citizens moving to West Germany totaled 197,000 in 1950, 165,000 in 1951, 182,000 in 1952 and 331,000 in 1953.[5][6] One reason for the sharp 1953 increase was fear of potential further Sovietization with the increasingly paranoid actions of Joseph Stalin in late 1952 and early 1953.[7] 226,000 had fled in the just the first six months of 1953.[8]

[edit] Erection of the Inner-German Border

By the early 1950s, the Soviet approach to controlling national movement, restricting emigration was emulated by most of the rest of the Eastern Bloc, including East Germany.[9] The restrictions presented a quandary for some Eastern Bloc states that had been more economically advanced and open than the Soviet Union, such that crossing borders seemed more natural -- especially between where no prior border existed between East and West Germany.[10]

Up until 1952, the lines between East Germany and the western occupied zones could be easily crossed in most places.[11] On April 1, 1952, East German leaders met the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in Moscow; during the discussions Stalin's foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov proposed that the East Germans should "introduce a system of passes for visits of West Berlin residents to the territory of East Berlin [so as to stop] free movement of Western agents" in the GDR. Stalin agreed, calling the situation "intolerable". He advised the East Germans to build up their border defenses, telling them that "The demarcation line between East and West Germany should be considered a border – and not just any border, but a dangerous one ... The Germans will guard the line of defense with their lives." [12]

Consequently, the Inner German border between the two German states was closed, and a barbed-wire fence erected. The border between the Western and Eastern sectors of Berlin, however, remained open, although traffic between the Soviet and the Western sectors was somewhat restricted. This resulted in Berlin becoming a magnet for East Germans desperate to escape life in the GDR, and also a flashpoint for tension between the superpowers--the United States and the Soviet Union.

In 1955, the Soviets passed a law transferring control over civilian access in Berlin to East Germany, which officially abdicated them for direct responsibility of matters therein, while passing control to a regime not recognized in the west.[13] When large numbers of East Germans then defected under the guise of "visits", the new East German state essentially eliminated all travel to the west in 1956.[11] Soviet East German ambassador Mikhail Pervukhin observed that "the presence in Berlin of an open and essentially uncontrolled border between the socialist and capitalist worlds unwittingly prompts the population to make a comparison between both parts of the city, which unfortunately, does not always turn out in favor of the Democratic [East] Berlin."[14]

[edit] The Berlin emigration loophole

With the closing of the Inner German border officially in 1952,[14] the border in Berlin remained considerably more accessible than the rest of the border because it was administered by all four occupying powers.[11] Accordingly, Berlin became the main route by which East Germans left for the West.[15] East Germany introduced a new passport law on December 11, 1957 that reduced the overall number of refugees leaving Eastern Germany, while drastically increasing the percentage of those leaving through West Berlin from 60% to well over 90% by the end of 1958.[14] Those actually caught trying to leave East Berlin were subjected to heavy penalties, but with no physical barrier and even subway train access to West Berlin, such measures were ineffective.[16] The Berlin sector border was essentially a "loophole" through which East Bloc citizens could still escape.[14] The 3.5 million East Germans that had left by 1961 totaled approximately 20% of the entire East German population.[16]

[edit] "Brain drain"

The emigrants tended to be young and well educated, leading to the brain drain feared by officials in East Germany.[4] Yuri Andropov, then the CPSU Director on Relations with Communist and Workers Parties of Socialist Countries, wrote an urgent letter on August 28, 1958, to the Central Committee about the significant 50% increase in the number of East German intelligentsia among the refugees.[17] Andropov reported that, while the East German leadership stated that they were leaving for economic reasons, testimony from refugees indicated that the reasons were more political than material.[17] He stated "the flight of the intelligentsia has reached a particularly critical phase."[17]

By 1960, the combination of World War II and the massive emigration westward left East Germany with only 61% of its population of working age, compared to 70.5% before the war.[16] The loss was disproportionately heavy among professionals -- engineers, technicians, physicians, teachers, lawyers and skilled workers.[16] The direct cost of manpower losses has been estimated at $7 billion to $9 billion, with East German party leader Walter Ulbricht later claiming that West Germany owed him $17 billion in compensation, including reparations as well as manpower losses.[16] In addition, the drain of East Germany's young population potentially cost it over 22.5 billion marks in lost educational investment.[18] The brain drain of professionals had become so damaging to the political credibility and economic viability of East Germany that the re-securing of the Soviet imperial frontier was imperative.[19]

[edit] Construction begins, 1961

On 15 June 1961, two months before the construction of the Berlin Wall started, First Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party and GDR State Council chairman Walter Ulbricht stated in an international press conference, "Niemand hat die Absicht, eine Mauer zu errichten!" (No one has the intention of erecting a wall!). It was the first time the colloquial term Mauer (wall) had been used in this context.

On Saturday, 12 August 1961, the leaders of the GDR attended a garden party at a government guesthouse in Döllnsee, in a wooded area to the north of East Berlin, at which time Ulbricht signed the order to close the border and erect a wall.

At midnight, the police and units of the East German army began to close the border and by Sunday morning, 13 August 1961, the border with West Berlin was closed. East German troops and workers had begun to tear up streets running alongside the border to make them impassable to most vehicles, and to install barbed wire entanglements and fences along the 156 km (97 miles) around the three western sectors and the 43 km (27 miles) which actually divided West and East Berlin.

The barrier was built slightly inside East Berlin or East German territory to ensure that it did not encroach on West Berlin at any point, and was later built up into the Wall proper, the first concrete elements and large blocks being put in place on August 15. During the construction of the Wall, NVA and KdA soldiers stood in front of it with orders to shoot anyone who attempted to defect. Additionally, chain fences, walls, minefields, and other obstacles were installed along the length of the inner-German border between East and West Germany.

[edit] Immediate effects

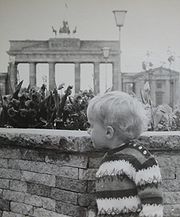

Due to the closure of the East-West sector boundary in Berlin, the vast majority of East Germans could no longer travel or emigrate to West Germany. Many families were split, while East Berliners employed in the West were cut off from their jobs; West Berlin became an isolated enclave in a hostile land. West Berliners demonstrated against the wall, led by their Mayor (Oberbürgermeister) Willy Brandt, who strongly criticized the United States for failing to respond. Allied intelligence agencies had hypothesized about a wall to stop the flood of refugees, but the main candidate for its location was around the perimeter of the city.

|

|||||

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. | |||||

John F. Kennedy had acknowledged in a speech on July 25, 1961, that the United States could hope to defend only West Berliners and West Germans; to attempt to stand up for East Germans would result only in an embarrassing downfall. Accordingly, the administration made polite protests at length via the usual channels, but without fervour, even though it was a violation of the postwar Potsdam Agreements, which gave the United Kingdom, France and the United States a say over the administration of the whole of Berlin. Indeed, a few months after the barbed wire was erected, the U.S. government informed the Soviet government that it accepted the Wall as "a fact of international life" and would not challenge it by force. U.S. and UK sources had expected the Soviet sector to be sealed off from West Berlin, which had appeared to be the best option the GDR and Soviet powers had at their disposal, but were surprised how long it had taken for a move of this kind. They also saw the wall as an end to concerns about a GDR/Soviet retaking or capture of the whole of Berlin; the wall would presumably have been an unnecessary project if such plans were afloat. Thus the possibility of a military conflict over Berlin decreased. [20]

The East German government claimed that the Wall was an "anti-Fascist protective rampart" ("antifaschistischer Schutzwall") intended to dissuade aggression from the West [21]. Another official justification was the activities of western agents in Eastern Europe [22]. A yet different explanation was that West Berliners were buying out state-subsidized goods in East Berlin. Most of these positions were, however, viewed with skepticism even in East Germany, even more so since most of the time, the border was only closed for citizens of East Germany travelling to the West, but not for residents of West Berlin travelling to the East[23]. The construction of the Wall had caused considerable hardship to families divided by it, and the view that the Wall was mainly a means of preventing the citizens of East Germany from entering West Berlin or fleeing was widely accepted.

An East German propaganda booklet published in 1955 outlined the seriousness of 'flight from the republic' to SED party agitators:

| “ | Both from the moral standpoint as well as in terms of the interests of the whole German nation, leaving the GDR is an act of political and moral backwardness and depravity.

Those who let themselves be recruited objectively serve West German Reaction and militarism, whether they know it or not. Is it not despicable when for the sake of a few alluring job offers or other false promises about a "guaranteed future" one leaves a country in which the seed for a new and more beautiful life is sprouting, and is already showing the first fruits, for the place that favors a new war and destruction? Is it not an act of political depravity when citizens, whether young people, workers, or members of the intelligentsia, leave and betray what our people have created through common labor in our republic to offer themselves to the American or British secret services or work for the West German factory owners, Junkers, or militarists? Does not leaving the land of progress for the morass of an historically outdated social order demonstrate political backwardness and blindness? ... [W]orkers throughout Germany will demand punishment for those who today leave the German Democratic Republic, the strong bastion of the fight for peace, to serve the deadly enemy of the German people, the imperialists and militarists.[24] |

” |

[edit] Secondary response

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2008) |

| This section has been nominated to be checked for its neutrality. Discussion of this nomination can be found on the talk page. (July 2008) |

It was clear both that West German morale needed lifting and that there was a serious potential threat to the viability of West Berlin. If West Berlin fell after all the efforts of the Berlin Airlift, how could any of America's other allies rely on it? On the other hand, in the face of any serious Soviet threat, an enclave like West Berlin could not be defended except with nuclear weapons.[25] As such, it was vitally important for the Americans to show the Soviets a display of strength and also placate West German and French pressure for a more serious response.

Accordingly, General Lucius D. Clay, an anti-communist who was known to have a firm attitude towards the Soviets, was sent to Berlin with ambassadorial rank as Kennedy's special advisor. He and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson arrived at Tempelhof Airport on the afternoon of Saturday August 19.

They arrived in a city defended by what would soon be known as the "Berlin Brigade", which then consisted of the 2nd and 3rd Battle Groups of the 6th Infantry, with Company F, 40th Armor. The battle groups were "pentatomic" (a flatter command structure with five battle groups instead of the old three regiments with three battalions, and also equipped with tactical nuclear weapons), with 1,362 officers and men each. On August 16, Kennedy had given the order for them to be reinforced. Early on August 19, the 1st Battle Group, 18th Infantry (commanded by Col. Glover S. Johns Jr.) was alerted.

On Sunday morning, lead elements arranged in a column of 491 vehicles and trailers carrying 1,500 men divided into five march units and left the Helmstedt-Marienborn checkpoint at 06:34. At Marienborn, the Soviet checkpoint next to Helmstedt on the West German/East German border, U.S. personnel were counted by guards. The column was 160 km (~100 miles) long, and covered 177 km (~110 miles) from Marienborn to Berlin in full battle gear, with VoPos (East German police) watching from beside trees next to the autobahn all the way along. The front of the convoy arrived at the outskirts of Berlin just before noon, to be met by Clay and Johnson, before parading through the streets of Berlin to an adoring crowd. At 04:00 on August 21, Lyndon Johnson left a visibly reassured West Berlin in the hands of Gen. Frederick O. Hartel and his brigade of 4,224 officers and men. Every three months for the next three and a half years, a new American battalion was rotated into West Berlin by autobahn to demonstrate Allied rights.

The creation of the Wall had important implications for both German states. By stemming the exodus of people from East Germany, the East German government was able to reassert its control over the country: in spite of discontent with the wall, economic problems caused by dual currency and the black market were largely eliminated, and the economy in the GDR began to grow. However, the Wall proved a public relations disaster for the communist bloc as a whole. Western powers used it in propaganda as a symbol of communist tyranny, particularly after the shootings of would-be defectors (which were later treated as acts of murder by the reunified Germany).

[edit] Layout and modifications

The Berlin Wall was more than 140 kilometres (87 mi) long. In June of 1962, a second, parallel fence some 100 metres (110 yd) farther into East German territory was built. The houses contained between the fences were razed and the inhabitants relocated, thus establishing the No Man's Land that later became known as The Death Strip. The No Man's Land was covered with raked gravel, rendering footprints easy to notice thus enabling officers to see which guards had neglected their task[26]; it offered no cover; most important, it offered clear fields of fire for the wall guards. Through the years, the Berlin Wall evolved through four versions:

- Wire fence (1961)

- Improved wire fence (1962–1965)

- Concrete wall (1965–1975)

- Grenzmauer 75 (Border Wall 75) (1975–1989)

The "fourth-generation wall", known officially as "Stützwandelement UL 12.11" (retaining wall element UL 12.11), was the final and most sophisticated version of the Wall. Begun in 1975[27] and completed about 1980,[28] it was constructed from 45,000 separate sections of reinforced concrete, each 3.6 metres (12 ft) high and 1.2 metres (3.9 ft) wide, and cost 16,155,000 East German Marks or about 3,638,000 United States Dollars.[29] The top of the wall was lined with a smooth pipe, intended to make it more difficult to scale. It was reinforced by mesh fencing, signal fencing, anti-vehicle trenches, barbed wire, dogs on long lines, "fakir beds" under balconies hanging over the "death strip", over 116 watchtowers,[30] and 20 bunkers. This version of the Wall is the one most commonly seen in photographs, and surviving fragments of the Wall in Berlin and elsewhere around the world are generally pieces of the fourth-generation Wall. The layout came to resemble the inner-German border in most technical aspects, except the Berlin Wall had no landmines and no Spring-guns[26].

[edit] Surrounding municipalities

Besides the sector-sector boundary within Berlin itself, the wall also separated West Berlin from the present-day state of Brandenburg. The following present-day municipalities, listed in counter-clockwise direction, share a border with former West Berlin:

- Oberhavel : Mühlenbecker Land (partially), Glienicke/Nordbahn, Hohen Neuendorf, Hennigsdorf

- Havelland : Schönwalde-Glien, Falkensee, Dallgow-Döberitz

- Potsdam (Urban district)

- Potsdam-Mittelmark : Stahnsdorf, Kleinmachnow, Teltow

- Teltow-Fläming : Großbeeren, Blankenfelde-Mahlow

- Dahme-Spreewald : Schönefeld (partially)

[edit] Official crossings and usage

There were eight border crossings between East and West Berlin, which allowed visits by West Berliners, West Germans, Western foreigners and Allied personnel into East Berlin, as well as visits by GDR citizens and citizens of other socialist countries into West Berlin, provided that they held the necessary permits. Those crossings were restricted according to which nationality was allowed to use it (East Germans, West Germans, West Berliners, other countries). The most famous was the vehicle and pedestrian checkpoint at the corner of Friedrichstraße and Zimmerstraße, also known as Checkpoint Charlie, which was restricted to Allied personnel and foreigners.

Several other border crossings existed between West Berlin and surrounding East Germany. These could be used for transit between West Germany and West Berlin, for visits by West Berliners into East Germany, for transit into countries neighbouring East Germany (Poland, Czechoslovakia, Denmark), and for visits by East Germans into West Berlin carrying a permit. After the 1972 agreements, new crossings were opened to allow West Berlin waste to be transported into East German dumps, as well as some crossings for access to West Berlin's exclaves (see Steinstücken).

Four autobahns connected West Berlin to West Germany, the most famous being the Berlin-Helmstedt autobahn, which entered East German territory between the towns of Helmstedt and Marienborn (Checkpoint Alpha), and which entered West Berlin at Dreilinden (Checkpoint Bravo) in southwestern Berlin. Access to West Berlin was also possible by railway (four routes) and by boat using canals and rivers.

Westerners could cross the border at Friedrichstraße station in East Berlin and at Checkpoint Charlie. When the Wall was erected, Berlin's complex public transit networks, the S-Bahn and U-Bahn, were divided with it.[28] Some lines were cut in half; many stations were shut down. Three Western lines traveled through brief sections of East Berlin territory, passing through eastern stations (called Geisterbahnhöfe, or ghost stations) without stopping. Both the eastern and western networks converged at Friedrichstraße, which became a major crossing point for those (mostly Westerners) with permission to cross.

[edit] Who could cross

West Germans and citizens of other Western countries could in general visit East Germany. Usually this involved application of a visa at an East German embassy several weeks in advance. Visas for day trips restricted to East Berlin were issued without previous application in a simplified procedure at the border crossing. However, East German authorities could refuse entry permits without stating a reason.

West Berliners initially could not visit East Berlin or East Germany at all. All crossing points were closed to them between 26 August 1961 and 17 December 1963. In 1963, negotiations between East and West resulted in a limited possibility for visits during the Christmas season that year ("Passierscheinregelung"). Similar very limited arrangements were made in 1964, 1965 and 1966.

In 1971, with the Four Power Agreement on Berlin, agreements were reached that allowed West Berliners to apply for visas to enter East Berlin and East Germany regularly, comparable to the regulations already in force for West Germans. However, East German authorities could still refuse entry permits.

East Berliners and East Germans could at first not travel to West Berlin or West Germany at all. This regulation remained in force essentially until the fall of the wall, but over the years several exceptions to these rules were introduced, the most significant being:

- Old age pensioners could travel to the West starting in 1964

- Visits of relatives for important family matters

- People who had to travel to the West for professional reasons (e.g. artists, truck drivers etc.)

However, each visit had to be applied for individually and approval was never guaranteed. In addition, even if travel was approved, GDR travellers could exchange only a very small amount of East German Marks into Deutsche Marks (DM), thus limiting the financial resources available for them to travel to the West. This led to the West German practice of granting a small amount of DM annually (Begrüßungsgeld, or "welcome money") to GDR citizens visiting West Germany and West Berlin, to help alleviate this situation.

Citizens of other East European countries were in general subject to the same prohibition on visiting Western countries as East Germans, though the applicable exception (if any) varied from country to country.

Allied military personnel and civilian officials of the Allied forces could enter and exit East Berlin without submitting to East German passport controls; likewise Soviet military patrols could enter and exit West Berlin. This was a requirement of the post-war Four Powers Agreements. A particular area of concern for the Western Allies involved official dealings with East German authorities when crossing the border, since Allied policy did not recognize the authority of the GDR to regulate Allied military traffic to and from West Berlin, as well as the Allied presence within Greater Berlin, including entry into, exit from, and presence within East Berlin; the Allies held that only the Soviet Union, and not the GDR, had authority to regulate Allied personnel in such cases. For this reason, elaborate procedures were established to prevent inadvertent recognition of East German authority when engaged in travel through the GDR and when in East Berlin. Special rules applied to travel by Western Allied military personnel assigned to the Military Liaison Missions accredited to the commander of Soviet forces in East Germany, located in Potsdam.

Allied personnel were restricted by policy when traveling by land to the following routes:

Transit between West Germany and West Berlin:

*Road: the Helmstedt-Berlin autobahn (A2) (Checkpoints Alpha and Bravo respectively). Soviet military personnel manned these checkpoints and processed Allied personnel for travel between the two points. Military personnel were required to be in uniform when travelling in this manner.

*Rail: Western Allied military personnel and civilian officials of the Allied forces were forbidden from using commercial train service between West Germany and West Berlin, due to the fact of GDR passport and customs controls when using them. Instead, the Allied forces operated a series of official ("duty") trains that travelled between their respective duty stations in West Germany and West Berlin. When transiting the GDR, the trains would follow the route between Helmstedt and Griebnitzsee, just outside of West Berlin. In addition to persons travelling on official business, authorized personnel could also use the duty trains for personal travel on a space-available basis. The trains travelled only at night, and as with transit by car, Soviet military personnel handled the processing of duty train travellers.

Entry into and exit from East Berlin: Checkpoint Charlie (as a pedestrian or riding in a vehicle)

As with military personnel, special procedures applied to travel by diplomatic personnel of the Western Allies accredited to their respective embassies in the GDR, again with the intent to prevent inadvertent recognition of East German authority when crossing between East and West Berlin, in order not to jeopardize the overall Allied position governing the freedom of movement by Allied forces personnel within all of Berlin.

Ordinary citizens of the Western Allied powers, not formally affiliated with the Allied forces, were authorized to use all designated transit routes through East Germany to and from West Berlin. Regarding travel to East Berlin, such persons could also use the Friedrichstraße train station to enter and exit the city, in addition to Checkpoint Charlie. In these instances, such travellers, unlike Allied personnel, had to submit to East German border controls.

[edit] Escape attempts

During the Wall's existence there were around 5,000 successful escapes to West Berlin. The number of people who died trying to cross the wall or as a result of the wall's existence has been disputed. The most vocal claims by Alexandra Hildebrandt, Director of the Checkpoint Charlie Museum and widow of the Museum's founder, estimated the death toll to be well above 200 [31], while an ongoing historic research group at the Center for Contemporary Historical Research (ZZF) in Potsdam has confirmed 136 deaths.[32] Guards were told by East German authorities that people attempting to cross the wall were criminals and needed to be shot: "Do not hesitate to use your firearm, not even when the border is breached in the company of women and children, which is a tactic the traitors have often used", they said. [3]

Early successful escapes involved people jumping the initial barbed wire or leaping out of apartment windows along the line but these ended as the wall was fortified. In order to solve these simple escape attempts, East German authorities no longer permitted apartments near the wall to be occupied and any building near the wall had to have their windows boarded up. On August 15, 1961, Conrad Schumann was the first East German border guard to escape by jumping the barbed wire to West Berlin. Later successful escape attempts included long tunnels, waiting for favorable winds and taking a hot air balloon, sliding along aerial wires, flying ultralights, and in one instance, simply driving a sports car at full speed through the basic, initial fortifications. When a metal beam was placed at checkpoints to prevent this kind of escape, up to four people (two in the front seats and possibly two in the boot) drove under the bar in a sports car that had been modified to allow the roof and wind screen to come away when it made contact with the beam. They simply lay flat and kept driving forward. This issue was rectified with zig-zagging roads at checkpoints.

Another airborne escape was by Thomas Krüger, who landed a Zlin Z 42M light aircraft of the Gesellschaft für Sport und Technik, an East German youth military training organization, at RAF Gatow. His aircraft, registration DDR-WOH, was dismantled and returned to the East Germans by road, complete with humorous slogans painted on by RAF airmen such as "Wish you were here" and "Come back soon". DDR-WOH is still flying today, but under the registration D-EWOH.

If an escapee was wounded in a crossing attempt and lay on the death strip, no matter how close they were to the Western wall, they could not be rescued for fear of triggering engaging fire from the 'Grepos', the East Berlin border guards. The guards often let fugitives bleed to death in the middle of this ground, like in the most notorious failed attempt, that of Peter Fechter (aged 18). He was shot and bled to death in full view of the Western media, on August 17, 1962. Fechter's death created negative publicity worldwide that led the leaders of East Berlin to place more restrictions on shooting in public places, and provide medical care for possible “would-be escapers”.[33]The last person to be shot while trying to cross the border was Chris Gueffroy on February 6, 1989.

[edit] "Mr. Gorbachev, Tear Down This Wall!"

An seminal moment in the years preceding the fall of the wall was Ronald Reagan's speech at the Brandenburg Gate on June 12, 1987. While commemorating the 750th anniversary of the founding of the city of Berlin, Reagan challenged Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev to liberate the Soviet bloc nations, saying

| “ | We welcome change and openness; for we believe that freedom and security go together, that the advance of human liberty can only strengthen the cause of world peace. There is one sign the Soviets can make that would be unmistakable, that would advance dramatically the cause of freedom and peace. General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization, come here to this gate. Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate. Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall![34] | ” |

[edit] The Fall, 1989

On August 23, 1989, Hungary removed its physical border defences with Austria, and in September more than 13,000 East German tourists in Hungary escaped to Austria. This set up a chain of events. The Hungarians prevented many more East Germans from crossing the border and returned them to Budapest. These East Germans flooded the West German embassy and refused to return to East Germany. The East German government responded by disallowing any further travel to Hungary, but allowed those already there to return. This triggered a similar incident in neighboring Czechoslovakia. On this occasion, the East German authorities allowed them to leave, providing that they used a train which transited East Germany on the way. This was followed by mass demonstrations within East Germany itself. (See Monday demonstrations in East Germany.) The longtime leader of East Germany, Erich Honecker, resigned on October 18, 1989, and was replaced by Egon Krenz a few days later. Honecker had predicted in January of that year that the wall would stand for a "hundred more years" if the conditions which had caused its construction did not change.

Protest demonstrations broke out all over East Germany in September 1989. Initially, they were of people wanting to leave to the West, chanting "Wir wollen raus!" ("We want out!"). Then protestors began to chant "Wir bleiben hier", ("We're staying here!"). This was the start of what East Germans generally call the "Peaceful Revolution" of late 1989. By November 4, the protests had swelled significantly, with a million people gathered that day in Alexanderplatz in East Berlin(Henslin, 07).

Meanwhile the wave of refugees leaving East Germany for the West had increased and had found its way through Czechoslovakia, tolerated by the new Krenz government and in agreement with the communist Czechoslovak government. In order to ease the complications, the politburo led by Krenz decided on November 9, to allow refugees to exit directly through crossing points between East Germany and West Germany, including West Berlin. On the same day, the ministerial administration modified the proposal to include private travel. The new regulations were to take effect on November 10. Günter Schabowski, the Party Secretary for Propaganda, had the task of announcing this; however he had been on vacation prior to this decision and had not been fully updated. Shortly before a press conference on November 9, he was handed a note that said that East Berliners would be allowed to cross the border with proper permission but given no further instructions on how to handle the information. These regulations had only been completed a few hours earlier and were to take effect the following day, so as to allow time to inform the border guards. However, nobody had informed Schabowski. He read the note out loud at the end of the conference and when asked when the regulations would come into effect, he assumed it would be the same day based on the wording of the note and replied "As far as I know effective immediately, without delay". After further questions from journalists he confirmed that the regulations included the border crossings towards West Berlin, which he had not mentioned until then.

Tens of thousands of East Berliners heard Schabowski's statement live on East German television and flooded the checkpoints in the Wall demanding entry into West Berlin. The surprised and overwhelmed border guards made many hectic telephone calls to their superiors, but it became clear that there was no one among the East German authorities who would dare to take personal responsibility for issuing orders to use lethal force, so there was no way for the vastly outnumbered soldiers to hold back the huge crowd of East German citizens. In face of the growing crowd, the guards finally yielded, opening the checkpoints and allowing people through with little or no identity checking. Ecstatic East Berliners were soon greeted by West Berliners on the other side in a celebratory atmosphere. November 9 is thus considered the date the Wall fell. In the days and weeks that followed, people came to the wall with sledgehammers in order to chip off souvenirs, demolishing lengthy parts of it in the process. These people were nicknamed "Mauerspechte" (wall woodpeckers).

The East German regime announced the opening of ten new border crossings the following weekend, including some in symbolic locations (Potsdamer Platz, Glienicker Brücke, Bernauer Straße). Crowds on both sides waited there for hours, cheering at the bulldozers who took parts of the Wall away to reinstate old roads. Photos and television footage of these events is sometimes mislabelled "dismantling of the Wall", even though it was merely the construction of new crossings. New border crossings continued to be opened through the middle of 1990, including the Brandenburg Gate on December 22, 1989.

West Germans and West Berliners were allowed visa-free travel starting December 23. Until then they could only visit East Germany and East Berlin under restrictive conditions that involved application for a visa several days or weeks in advance, and obligatory exchange of at least 25 DM per day of their planned stay, all of which hindered spontaneous visits. Thus, in the weeks between November 9 and December 23, East Germans could travel "more freely" than Westerners.

Technically the Wall remained guarded for some time after November 9, though at a decreasing intensity. In the first months, the East German military even tried to repair some of the damages done by the "wall peckers". Gradually these attempts ceased, and guards became more lax, tolerating the increasing demolitions and "unauthorized" border crossing through the holes. On June 13, 1990, the official dismantling of the Wall by the East German military began in Bernauer Straße. On July 1, the day East Germany adopted the West German currency, all border controls ceased, although the inter-German border had become meaningless for some time before that. The dismantling continued to be carried out by military units (after unification under the Bundeswehr) and lasted until November 1991. Only a few short sections and watchtowers were left standing as memorials.

The fall of the Wall was the first step toward German reunification, which was formally concluded on October 3, 1990.

[edit] Celebrations

On December 25, 1989, Leonard Bernstein gave a concert in Berlin celebrating the end of the Wall, including Beethoven's 9th symphony (Ode to Joy) with the word "Joy" (Freude) changed to "Freedom" (Freiheit) in the text sung. The orchestra and choir were drawn from both East and West Germany, as well as the United Kingdom, France, the Soviet Union, and the United States.[35]

Roger Waters performed the Pink Floyd album The Wall in Potsdamer Platz on 21 July 1990, with guests including Scorpions, Bryan Adams, Sinéad O'Connor, Thomas Dolby, Joni Mitchell, Marianne Faithfull, Levon Helm, Rick Danko and Van Morrison. David Hasselhoff performed his song "Looking for Freedom", which was very popular in Germany at that time, standing on the Berlin wall.

Over the years there has been repeatedly a controversial debate [36] whether November 9 would have made a suitable German national holiday, often initiated by former members of political opposition in East Germany like Werner Schulz[37]. Besides the emotional apogee of East Germany's peaceful revolution November 9 is also the date of the end of the Revolution of 1848 and the date of the declaration of the first German republic, the Weimar Republic, in 1918. However, November 9 is also the anniversary of the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch and the infamous Kristallnacht pogroms of 1938 and, therefore, October 3 was chosen instead. Part of this decision was that the East German government wanted to conclude reunification before East Germany could celebrate a 41st anniversary on October 7, 1990..[citation needed]

[edit] Legacy

|

A section of the Berlin Wall used as the center of "Liberty Plaza" on the campus of Chapman University in the United States |

Remaining stretch of the Wall near Ostbahnhof in Friedrichshain, August 2006 |

Remains of the Wall near Potsdamer Platz, August 2007 |

|

Little is left of the Wall at its original site, which was destroyed almost everywhere. Three long sections are still standing: an 80-meter (263 ft) piece of the "first (westernmost) wall" at the site of the former Gestapo headquarter half way between Checkpoint Charlie and Potsdamer Platz; a longer section of the "second (easternmost) wall" along the Spree River near the Oberbaumbrücke nicknamed East Side Gallery; and a third section with hints of the full installation, but partly reconstructed, in the north at Bernauer Straße, which was turned into a memorial in 1999. Some other isolated fragments and a few watchtowers also remain in various parts of the city. None still accurately represent the Wall's original appearance. They are badly damaged by souvenir seekers, as fragments of the Wall were taken and sold around the world. Appearing both with and without certificates of authenticity, these fragments are now a staple on the online auction service eBay as well as German souvenir shops. Today, the eastern side is covered in graffiti that did not exist while the Wall was guarded by the armed soldiers of East Germany. Previously, graffiti appeared only on the western side. Along the tourist areas of the city centre, the city government has marked the location of the former wall by a row of cobblestones in the street. In most places only the "first" wall is marked, except near Potsdamer Platz where the stretch of both walls is marked, giving visitors an impression of the dimension of the barrier system.

[edit] Museum

Fifteen years after the fall, a private museum rebuilt a 200-metre (656 ft) section close to Checkpoint Charlie, although not in the location of the original wall. They also raised more than 1,000 crosses in memory of those who died attempting to flee to the West. The memorial was installed in October 2004 and demolished in July 2005.[38]

[edit] Cultural differences

Even now, some years after reunification, there is still talk in Germany of cultural differences between East and West Germans (colloquially Ossis and Wessis), sometimes described as "Mauer im Kopf" ("The wall in the head"). A September 2004 poll found that 25% of West Germans and 12% of East Germans wished that East Germany and West Germany were again cut off by the Berlin Wall.[39]

[edit] Fulton, Missouri

A unique piece of the wall is in the small town of Fulton, Missouri at Westminster College. The college was the site of the famous 'Iron Curtain' speech given by Winston Churchill near the beginning of the cold war. A piece of artwork made out of a section of the wall was created by the granddaughter of Churchill and placed on the school grounds at the Winston Churchill Memorial and Library.

[edit] See also

- Berlin border crossings

- Brandenburg Gate

- Der Tunnel, a film about a mass evacuation to West Berlin through a tunnel

- Diplomatic incident of October 1961 – See Checkpoint Charlie

- Eastern Bloc

- List of Berlin Wall portions

- List of walls

- Operation Gold

- Ostalgie

- Panmunjeom, the Korean equivalent of the wall and the last standing front of the Cold War after the fall of the wall.

- Removal of Hungary's border fence

- Schießbefehl

- Solidarity Movement

- Tear down this wall

- The Berlin Wall (arcade game)

- The Wall - Live in Berlin, a rock opera/concert by Roger Waters after "The real wall" was torn down. A huge "new wall" made out of bricks was made, then demolished at the end.

[edit] Notes

- ^ Freedom! - TIME

- ^ Forschungsprojekt „Die Todesopfer an der Berliner Mauer, 1961-1989“: BILANZ (Stand: 7. August 2008) (in German)

- ^ a b "E German 'licence to kill' found". BBC. 2007-08-12. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/6943093.stm. Retrieved on 2007-08-12. "A newly discovered order is the firmest evidence yet that the communist regime gave explicit shoot-to-kill orders, says Germany's director of Stasi files."

- ^ a b Thackeray 2004, p. 188

- ^ Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Arbeit und Sozialordnung, Familie und Frauen, Statistik Spätaussiedler Dezember 2007, p.3 (in German)

- ^ Loescher 2001, p. 60

- ^ Loescher 2001, p. 68

- ^ Dale 2005, p. 17

- ^ Dowty 1989, p. 114

- ^ Dowty 1989, p. 116

- ^ a b c Dowty 1989, p. 121

- ^ Harrison 2003, p. 240-fn

- ^ Harrison 2003, p. 98

- ^ a b c d Harrison 2003, p. 99

- ^ Paul Maddrell, Spying on Science: Western Intelligence in Divided Germany 1945–1961, p. 56. Oxford University Press, 2006

- ^ a b c d e Dowty 1989, p. 122

- ^ a b c Harrison 2003, p. 100

- ^ Volker Rolf Berghahn, Modern Germany: Society, Economy and Politics in the Twentieth Century, p. 227. Cambridge University Press, 1987

- ^ Pearson 1998, p. 75

- ^ Taylor, Frederick. The Berlin Wall: 13 August 1961 - 9 November 1989. Bloomsbury 2006

- ^ Goethe-Institut - Topics - German-German History Goethe-Institut

- ^ "Die Regierungen der Warschauer Vertragsstaaten wenden sich an die Volkskammer und an die Regierung der DDR mit dem Vorschlag, an der Westberliner Grenze eine solche Ordnung einzuführen, durch die der Wühltätigkeit gegen die Länder des sozialistischen Lagers zuverlässig der Weg verlegt und ringsum das ganze Gebiet West-Berlins eine verlässliche Bewachung gewährleistet wird." Die Welt: Berlin wird geteilt

- ^ Neues Deutschland: Normales Leben in Berlin, Aug. 14th, 1961

- ^ English translation of "Wer die Deutsche Demokratische Republik verläßt, stellt sich auf die Seite der Kriegstreiber" ("He Who Leaves the German Democratic Republic Joins the Warmongers", Notizbuch des Agitators ("Agitator's Notebook"), published by the Socialist Unity Party's Agitation Department, Berlin District, November 1955.

- ^ First Strike Options and the Berlin Crisis, September 1961

- ^ a b According to Hagen Koch, former Stasi-officer, in Geert Mak's documentary In Europa, episode 1961 - DDR, January 25, 2009

- ^ Facts of Berlin Wall - History of Berlin Wall

- ^ a b http://www.wall-berlin.org/gb/mur.htm

- ^ Fourth Generation of Berlin Wall - History of Berlin Wall

- ^ " The Berlin wall : History of Berlin Wall : Facts "

- ^ Chronik der Mauer: Todesopfer an der Berliner Mauer (in German)

- ^ http://www.chronik-der-mauer.de/index.php/de/Start/Index/id/593792 Center for Contemporary Historical Research (Zentrum für Zeithistorische Forschung Potsdam e.V) in German

- ^ Taylor, Frederick . The Berlin Wall: A World Divided 1961-1989. London: Harper Perennial, 2006.

- ^ "Remarks at the Brandenberg Gate". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. http://www.reaganfoundation.org/reagan/speeches/wall.asp. Retrieved on 2008-02-09.

- ^ Naxos (2006). "Ode To Freedom - Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 (NTSC)". Naxos.com Classical Music Catalogue. http://www.naxos.com/catalogue/item.asp?item_code=2072038. Retrieved on 2006-11-26. This is the publisher's catalogue entry for a DVD of Bernstein's Christmas 1989 "Ode to Freedom" concert. David Hasselhoff sang during the fall of the Berlin wall.

- ^ Sven Felix Kellerhof, Alan Posener (2007). "Soll der 9. November Nationalfeiertag werden?". Welt Online. http://debatte.welt.de/kontroverse/48213/soll+der+9+november+nationalfeiertag+werden. Retrieved on 2009-02-22.

- ^ Jörg Aberger (2004-09-07). "Debatte: Thierse fordert neuen Nationalfeiertag". Spiegel Online. http://www.spiegel.de/kultur/gesellschaft/0,1518,316977,00.html. Retrieved on 2009-02-22.

- ^ Furlong, Ray (July 5, 2005). "Berlin Wall memorial is torn down". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4651823.stm. Retrieved on 2006-02-23.

- ^ Reuters (September 8, 2004). "One in 5 Germans wants Berlin Wall rebuilt". MSNBC. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/5942091/. Retrieved on 2006-02-23.

[edit] References

- Böcker, Anita (1998), Regulation of Migration: International Experiences, Het Spinhuis, ISBN 9055890952

- Buckley, William F., Jr. (2004). The Fall of the Berlin Wall. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-26736-8.

- Cate, Curtis (1978). The Ides of August: The Berlin Wall Crisis—1961. New York City: M. Evans.

- Dale, Gareth (2005), Popular Protest in East Germany, 1945-1989: Judgements on the Street, Routledge, ISBN 071465408

- Dowty, Alan (1989), Closed Borders: The Contemporary Assault on Freedom of Movement, Yale University Press, ISBN 0300044984

- Harrison, Hope Millard (2003), Driving the Soviets Up the Wall: Soviet-East German Relations, 1953-1961, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0691096783

- Catudal, Honoré M. (1980). Kennedy and the Berlin Wall Crisis. West Berlin: Berlin Verlag.

- Hertle, Hans-Hermann (2007). The Berlin Wall. Bonn: Federal Centre for Political Education.

- Kennedy, John F.. "July 25, 1961 speech". http://www.jfklibrary.org/Historical+Resources/Archives/Reference+Desk/Speeches/JFK/003POF03BerlinCrisis07251961.htm.

- Loescher, Gil (2001), The UNHCR and World Politics: A Perilous Path, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0198297165

- Maclean, Rory (1992). Stalin's Nose: Across the Face of Europe. London: HarperCollins.

- Mynz, Rainer (1995), Where Did They All Come From? Typology and Geography of European Mass Migration In the Twentieth Century; EUROPEAN POPULATION CONFERENCE CONGRESS EUROPEAN DE DEMOGRAPHE, United Nations Population Division

- Pearson, Raymond (1998), The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Empire, Macmillan, ISBN 0312174071

- Schneider, Peter (2005). The Wall Jumper. London: Penguin Classics.

- Friedrich, Thomas (writer),and Harry Hampel (photos) (1996). Wo die Mauer War/Where was the Wall?. Berlin: Nicolai. ISBN 3875846958.

- Taylor, Frederick. The Berlin Wall: 13 August 1961 - 9 November 1989. Bloomsbury 2006

- Thackeray, Frank W. (2004), Events that changed Germany, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0313328145

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Berlin Wall |

- Freedom Without Walls: German Missions in the United States Looking Back at the Fall of the Berlin Wall - official homepage in English

- Chronicle of the Wall Most comprehensive multi-media source of information on this topic

- The Berlin Wall Original reports and pictures from The Times

- Chronik der Mauer Chronicle of the Wall in German

- Information Berlin Wall and East-Berlin (in German)

- Retracing the Berlin Wall

- Bernauer Straße Memorial website

- Information on the East German border system (in German)

- Allied Forces in Berlin (FR, UK & US Berlin Brigade)

- Photographs of time of the Fall as well as updates on the current situation in Germany

- Reports on reinforcements to Berlin Brigade

- JFK speech clarifying limits of American protection

- "Berlin 1969" includes sections on Helmstedt-Berlin rail operations.

- Includes articles on rail transport for Berlin during the Cold War. (large files)

- Berlin 1983: Berlin and the Wall in the early 1980s

- Berlin Life: A concise but thorough history of the wall

- Berlin Wall: Past and Present

- The Lives of Others official website

- Important Berlin Wall Dates

- The Lost Border: Photographs of the Iron Curtain

- Dossier: The Fall of the Wall – New Perspectives on 1989

[edit] Images and personal accounts

- Comprehensive Gallery (1961 to 1990) from the website Chronicle of the Wall

- Gallery of annotated photographs of the Berlin Wall

- Virtual e-Tours "The Wall" Shockwave Player required

- Photos of the Berlin Wall by Georges Rosset

- Photos of the Berlin Wall 1989 to 1999

- (Italian) Borders: spotting the past along Berlin death strip. 2007 BW photo gallery.

- Berlin Wall Pieces for Sale

- Berlin Wall Panorama of the East Side Gallery

- One Day In Berlin: Tracing The Wall

- Berlin Wall Online, Chronicle of the Berlin Wall history includes an archive of photographs and texts

- Personal Account of the Fall of the Berlin Wall

- Berlin Wall, Past and Present, Descriptions, Videos, Images of Berlin Wall

- Berlin Wall - Personal Stories

- Photos of the Berlin Wall 1962-1990 (German text)

- A large number of collected images in the Flickr Berlin Wall group

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||