Islamic architecture

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Islamic architecture encompasses a wide range of both secular and religious styles from the foundation of Islam to the present day, influencing the design and construction of buildings and structures in Islamic culture.

The principal Islamic architectural types are: the Mosque, the Tomb, the Palace and the Fort. From these four types, the vocabulary of Islamic architecture is derived and used for buildings of lesser importance such as public baths, fountains and domestic architecture.[1][2]

Contents |

[edit] History

In 630C.E. the Islamic prophet Muhammad's army reconquered the city of Mecca from the Banu Quraish tribe. The Kaaba sanctuary was rebuilt and re-dedicated to Islam, the reconstruction being carried out before the prophet Muhammad's death in 632C.E. by a shipwrecked Abyssinian carpenter in his native style. This sanctuary was amongst the first major works of Islamic architecture. Later doctrines of Islam dating from the eighth century and originating from the Hadith, forbade the use of humans and animals[1] in architectural design, in order to obey God's command (and thou shalt not make for thyself an image or idol of God) and also (thou shalt have no god before me) from the ten commandments and similar Islamic teachings. For Jews and Muslims veneration violates these commandments. They read these commandments as prohibiting the use of idols and images during worship in any way.

In the 7th century, Muslim armies conquered a huge expanse of land. Once the Muslims had taken control of a region, their first need was for somewhere to worship - a mosque. The simple layout provided elements that were to be incorporated into all mosques and the early Muslims put up simple buildings based on the model of the Prophet's house or adapted existing buildings for their own use.

Recently discoveries have shown that quasicrystal patterns were first employed in the girih tiles found in medieval Islamic architecture dating back over five centuries ago. In 1998, Professor Peter Lu of Harvard University and Professor Paul Steinhardt of Princeton University published a paper in the journal Science suggesting that girih tilings possessed properties consistent with self-similar fractal quasicrystalline tilings such as the Penrose tilings, predating them by five centuries.[3][4]

[edit] Influences and styles

A specifically recognisable Islamic architectural style emerged soon after the time of Muhammad, developing from localized adaptations of Egyptian, Byzantine, and Persian/Sassanid models. An early example may be identified as early as 691 AD with the completion of the Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhrah) in Jerusalem. It featured interior vaulted spaces, a circular dome, and the use of stylized repeating decorative patterns (arabesque).

The Great Mosque of Samarra in Iraq, completed in 847 AD, combined the hypostyle architecture of rows of columns supporting a flat base above which a huge spiraling minaret was constructed.

The Hagia Sophia in Istanbul also influenced Islamic architecture. When the Ottomans captured the city from the Byzantines, they converted the basilica to a mosque (now a museum) and incorporated Byzantine architectural elements into their own work (e.g. domes). The Hagia Sophia also served as a model for many Ottoman mosques such as the Shehzade Mosque, the Suleiman Mosque, and the Rüstem Pasha Mosque.

Distinguishing motifs of Islamic architecture have always been ordered repetition, radiating structures, and rhythmic, metric patterns. In this respect, fractal geometry has been a key utility, especially for mosques and palaces. Other significant features employed as motifs include columns, piers and arches, organized and interwoven with alternating sequences of niches and colonnettes.[5] The role of domes in Islamic architecture has been considerable. Its usage spans centuries, first appearing in 691 with the construction of the Dome of the Rock, and recurring even up until the 17th century with the Taj Mahal. As late as the 19th century, Islamic domes had been incorporated into Western architecture.[6][7]

[edit] Persian architecture

The Islamic conquest of Persia in the 7th century led early Islamic architects to borrow and adopt some traditions and ways of the fallen Persian empire. Islamic architecture thus borrows heavily from Persian architecture and in many ways can be called an extension and further evolution of Persian architecture.

Many cities, including Baghdad, were based on precedents such as Firouzabad in Persia. In fact, it is now known that the two designers hired by al-Mansur to plan the city's design were Naubakht (نوبخت), a former Persian Zoroastrian, and Mashallah (ماشاءالله), a former Jew from Khorasan, Iran.

Persian-style mosques are characterized by their tapered brick pillars, large arcades and arches each supported by several pillars. In South Asia, elements of Hindu architecture were employed, but were later superseded by Persian designs.[8]

[edit] Moorish architecture

Construction of the Great Mosque at Cordoba (now a cathedral) beginning in 785 CE marks the beginning of Islamic architecture in the Iberian peninsula and North Africa (see Moors). The mosque is noted for its striking interior arches. Moorish architecture reached its peak with the construction of the Alhambra, the magnificent palace/fortress of Granada, with its open and breezy interior spaces adorned in red, blue, and gold. The walls are decorated with stylize foliage motifs, Arabic inscriptions, and arabesque design work, with walls covered in glazed tile. Moorish architecture has its roots deeply established in the Arab tradition of architecture and design established during the era of the first Caliphate of the Umayyads in the Levant circa 660AD with its capital Damascus having very well preserved examples of fine Arab Islamic design and geometrics, including the carmen, which is the typical Damascene house, opening on the inside with a fountain as the house's centre piece.

Even after the completion of the Reconquista, Islamic influence had a lasting impact on the architecture of Spain. In particular, medieval Spaniards used the Mudéjar style, highly influenced by Islamic design. One of the best examples of the Moors' lasting impact on Spanish architecture is the Alcázar of Seville.

[edit] Turkistan (Timurid) architecture

Timurid architecture is the pinnacle of Islamic art in Central Asia. Spectacular and stately edifices erected by Timur and his successors in Samarkand and Herat helped to disseminate the influence of the Ilkhanid school of art in India, thus giving rise to the celebrated Mughal school of architecture. Timurid architecture started with the sanctuary of Ahmed Yasawi in present-day Kazakhstan and culminated in Timur's mausoleum Gur-e Amir in Samarkand. The style is largely derived from Persian architecture. Axial symmetry is a characteristic of all major Timurid structures, notably the Shah-e Zendah in Samarkand and the mosque of Gowhar Shad in Mashhad. Double domes of various shapes abound, and the outsides are perfused with brilliant colors.

[edit] Ottoman Turkish architecture

| This article may contain wording that promotes the subject in a subjective manner without imparting real information. Please remove or replace such wording or find sources which back the claims. |

The most numerous and largest of mosques exist in Turkey, which obtained influence from Byzantine, Persian and Syrian-Arab designs. Turkish architects implemented their own style of cupola domes.[8] The architecture of the Turkish Ottoman Empire forms a distinctive whole, especially the great mosques by and in the style of Sinan, like the mid-16th century Suleiman Mosque. For almost 500 years Byzantine architecture such as the church of Hagia Sophia served as models for many of the Ottoman mosques such as the Shehzade Mosque, the Suleiman Mosque, and the Rüstem Pasha Mosque.

The Ottomans mastered the technique of building vast inner spaces confined by seemingly weightless yet massive domes, and achieving perfect harmony between inner and outer spaces, as well as light and shadow. Islamic religious architecture which until then consisted of simple buildings with extensive decorations, was transformed by the Ottomans through a dynamic architectural vocabulary of vaults, domes, semidomes and columns. The mosque was transformed from being a cramped and dark chamber with arabesque-covered walls into a sanctuary of esthetic and technical balance, refined elegance and a hint of heavenly transcendence.

[edit] Fatimid architecture

In architecture, the Fatimids followed Tulunid techniques and used similar materials, but also developed those of their own. In Cairo, their first congregational mosque was al-Azhar mosque ("the splendid") founded along with the city (969–973), which, together with its adjacent institution of higher learning (al-Azhar University), became the spiritual center for Ismaili Shia. The Mosque of al-Hakim (r. 996–1013), an important example of Fatimid architecture and architectural decoration, played a critical role in Fatimid ceremonial and procession, which emphasized the religious and political role of the Fatimid caliph. Besides elaborate funerary monuments, other surviving Fatimid structures include the Mosque of al-Aqmar (1125) as well as the monumental gates for Cairo's city walls commissioned by the powerful Fatimid emir and vizier Badr al-Jamali (r. 1073–1094).

Al-Hakim Mosque (990-1012) was renovated by Dr. Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin (head of Dawoodi Bohra community) and Al-Jame-al-Aqmar built in 1125 in Cairo, Egypt features with its Fatimi philosophy and symbolism and bring its architecture vividly to life.

"The Fatemi rulers in North Africa and Egypt made the masjid the focal point of the uninterrupted flow of both the water of life and water of learning. They fostered noble traditions of thought and philosophy. They Produced and preserved an immense wealth of literature. They founded Cairo and Al-Azher university. They built Jame-Anwer, the second largest masjid in Egypt which was restored and renovated in 1982 by the 52nd Fatemi Dai His Holiness Dr. Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin(TUS). They initiated an efflorescence and resurgence of art, culture and thought which posterity remembers as the resplendent Fatemi civilization and which to this day nourishes human intellect and imparts strength and richness to life and living. Al-Jamea-tus-Saifiyah today is the continuing link in that long chain of centuries which inspired scholarship, valiant leadership and lofty thought." By: Dr. Y. Najmuddin, Rector, Al-Jamea-tus-Saifiyah.

[edit] Mamluk architecture

The reign of the Mamluks (1250-1517 AD) marked a breathtaking flowering of Islamic art which is most visible in old Cairo. Religious zeal made them generous patrons of architecture and art. Trade and agriculture flourished under Mamluk rule, and Cairo, their capital, became one of the wealthiest cities in the Near East and the center of artistic and intellectual activity. This made Cairo, in the words of Ibn Khaldun, "the center of the universe and the garden of the world", with majestic domes, courtyards, and soaring minarets spread across the city.

The architectural identity of Mamluk religious monuments stems from the major purpose that individuals erected their own memorials, therefore adding a high degree of individuality. Each building reflected the patron’s individual tastes, choices, and name. Mamluk architecture is oftentimes categorized more by the reigns of the major sultan, than a specific design. Interestingly, the mamluk elite were often more knowledgeable in the art of buildings than many historians.[9] Since the Mamluks had both wealth and power, the overall moderate proportions of Mamluk architecture -- compared to Timurid or classical Ottoman styles-- is due to the individual decisions of patrons who preferred to sponsor multiple projects. The sponsors of the mosques of Al-Zahir Baybars, al-Nasir Muhammad, Faraj, al-Mu’ayyad, Barsbay, Qaytbay and al-Ghawri all preferred to build several mosques in the capital rather than focusing on one colossal monument. Patrons used architecture to strengthen their religious and social roles within the community.

While the organization of Mamluk monuments varied, the funerary dome and minaret were constant leitmotifs. These attributes are prominent features in a Mamluk mosque’s profile and were significant in the beautification of the city skyline. In Cairo, the funerary dome and minaret were respected as symbols of commemoration and worship[10]. Patrons used these visual attributes to express their individuality by decorating each dome and minaret with distinct patterns. Patterns carved on domes ranged from ribs and zigzags to floral and geometric star designs. The funerary dome of Aytimish al-Bajasi and the mausoleum dome of Qaytbay’s sons reflect the diversity and detail of Mamluk architecture. Therefore the creativity of Mamluk builders was effectively emphasized with these leitmotifs.

Expanding on the Fatimids concept of street-adjusted mosque facades, the Mamluks developed their architecture to enhance street vistas. In addition, new aesthetic concepts and architectural solutions were created to reflect their assumed role in history. By 1285 the essential features of Mamluk architecture were already established in the complex of Sultan Qalawan. However, it took three decades for the Mamluks to create a new and distinct architecture. By 1517, the Ottoman conquest brought Mamluk architecture to an end without a term of decadence. [11]

The Mamluk utilized chiaroscuro and dappled light effects in their buildings. Mamluk history is divided into two periods based on different dynastic lines: the Bahri Mamluks (1250–1382) of Qipchaq Turkic origin from southern Russia, named after the location of their barracks on the Nile and the Burji Mamluks (1382–1517) of Caucasian Circassian origin, who were quartered in the citadel. The Bahri reign defined the art and architecture of the entire Mamluk period. Mamluk decorative arts—especially enameled and gilded glass, inlaid metalwork, woodwork, and textiles—were prized around the Mediterranean as well as in Europe, where they had a profound impact on local production. The influence of Mamluk glassware on the Venetian glass industry is only one such example.

The reign of Baybars's ally and successor, Qala’un (r. 1280–90), initiated the patronage of public and pious foundations that included madrasas, mausolea, minarets, and hospitals. Such endowed complexes not only ensured the survival of the patron's wealth but also perpetuated his name, both of which were endangered by legal problems relating to inheritance and confiscation of family fortunes. Besides Qala’un's complex, other important commissions by Bahri Mamluk sultans include those of al-Nasir Muhammad (1295–1304) as well as the immense and splendid complex of Hasan (begun 1356).

The Burji Mamluk sultans followed the artistic traditions established by their Bahri predecessors. Mamluk textiles and carpets were prized in international trade. In architecture, endowed public and pious foundations continued to be favored. Major commissions in the early Burji period in Egypt included the complexes built by Barquq (r. 1382–99), Faraj (r. 1399–1412), Mu’ayyad Shaykh (r. 1412–21), and Barsbay (r. 1422–38).

In the eastern Mediterranean provinces, the lucrative trade in textiles between Iran and Europe helped revive the economy. Also significant was the commercial activity of pilgrims en route to Mecca and Medina. Large warehouses, such as the Khan al-Qadi (1441), were erected to satisfy the surge in trade. Other public foundations in the region included the mosques of Aqbugha al-Utrush (Aleppo, 1399–1410) and Sabun (Damascus, 1464) as well as the Madrasa Jaqmaqiyya (Damascus, 1421).

In the second half of the fifteenth century, the arts thrived under the patronage of Qa’itbay (r. 1468–96), the greatest of the later Mamluk sultans. During his reign, the shrines of Mecca and Medina were extensively restored. Major cities were endowed with commercial buildings, religious foundations, and bridges. In Cairo, the complex of Qa’itbay in the Northern Cemetery (1472–74) is the best known and admired structure of this period. Building continued under the last Mamluk sultan, Qansuh al-Ghawri (r. 1501–17), who commissioned his own complex (1503–5); however, construction methods reflected the finances of the state. Though the Mamluk realm was soon incorporated into the Ottoman empire (1517), Mamluk visual culture continued to inspire Ottoman and other Islamic artistic traditions.

[edit] Indo-Islamic (Mughal) architecture

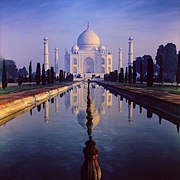

Another distinctive sub-style is the architecture of the Mughal Empire in India in the 16th century and a fusion of Arabic, Persian and Hindu elements. The Mughal emperor Akbar constructed the royal city of Fatehpur Sikri, located 26 miles west of Agra, in the late 1500s. The most famous example of Mughal architecture is the Taj Mahal, the "teardrop on eternity," completed in 1648 by emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his wife Mumtaz Mahal who died while giving birth to their 14th child. The extensive use of precious and semiprecious stones as inlay and the vast quantity of white marble required nearly bankrupted the empire. The Taj Mahal is completely symmetric except for Shah Jahan's sarcophagus, which is placed off center in the crypt room below the main floor. This symmetry extended to the building of an entire mirror mosque in red sandstone to complement the Mecca-facing mosque place to the west of the main structure. Another structure that showed great depth of Mughal influence was the Shalimar Gardens.

[edit] Sino-Islamic architecture

The first Chinese mosque was established in the 7th century during the Tang Dynasty in Xi'an. The Great Mosque of Xi'an, whose current buildings date from the Ming Dynasty, does not replicate many of the features often associated with traditional mosques. Instead, it follows traditional Chinese architecture. Some Chinese mosques in parts of western China were more likely to incorporate minarets and domes while eastern Chinese mosques were more likely to look like pagodas.[12]

An important feature in Chinese architecture is its emphasis on symmetry, which connotes a sense of grandeur; this applies to everything from palaces to mosques. One notable exception is in the design of gardens, which tends to be as asymmetrical as possible. Like Chinese scroll paintings, the principle underlying the garden's composition is to create enduring flow; to let the patron wander and enjoy the garden without prescription, as in nature herself.

Chinese buildings may be built with either red or grey bricks, but wooden structures are the most common; these are more capable of withstanding earthquakes, but are vulnerable to fire. The roof of a typical Chinese building is curved; there are strict classifications of gable types, comparable with the classical orders of European columns.

Most mosques have certain aspects in common with each other however as with other regions Chinese Islamic architecture reflects the local architecture in its style. China is renowned for its beautiful mosques, which resemble temples. However in western China the mosques resemble those of the Arab World, with tall, slender minarets, curvy arches and dome shaped roofs. In northwest China where the Chinese Hui have built their mosques, there is a combination of eastern and western styles. The mosques have flared Buddhist style roofs set in walled courtyards entered through archways with miniature domes and minarets (see Beytullah Mosque).[13]

[edit] Sub-Saharan African Islamic architecture

In West Africa, Islamic merchants played a vital role in the Western Sahel region since the Kingdom of Ghana. At Kumbi Saleh, locals lived in domed-shaped dwellings in the king's section of the city, surrounded by a great enclosure. Traders lived in stone houses in a section which possessed 12 beautiful mosques (as described by al-bakri), one centered on Friday prayer. [14] The king is said to have owned several mansions, one of which was sixty-six feet long, forty-two feet wide, contained seven rooms, was two stories high, and had a staircase; with the walls and chambers filled with sculpture and painting.[15] Sahelian architecture initially grew from the two cities of Djenné and Timbuktu. The Sankore Mosque in Timbuktu, constructed from mud on timber, was similar in style to the Great Mosque of Djenné.

[edit] Contemporary architecture

| Please help improve this article or section by expanding it. Further information might be found on the talk page. (November 2007) |

Modern Islamic architecture has recently been taken to a new level with such buildings being erected such as the Burj Dubai, which is soon to be the world's tallest building. The Burj Dubai's design is derived from the patterning systems embodied in Islamic architecture, with the triple-lobed footprint of the building based on an abstracted version of the desert flower hymenocallis which is native to the Dubai region. Nature and flowers have often been the focal point in most traditional Islamic designs. Many modern interpretations of Islamic architecture can be found in Dubai due to the architectural boom of the Arab World. Yet to be built is Madinat al-Hareer in Kuwait which also has modern versions of Islamic architecture in its epically tall tower.

Another example of modern Islamic architecture is the King Abdulaziz International Airport's Hajj Terminal, designed for pilgims on the Hajj in Saudi Arabia. The terminal's Bangladeshi architect Fazlur Khan received the Aga Khan Award for Architecture for "An Outstanding Contribution to Architecture for Muslims". Khan was also the inventor of the tube structure design used in all supertall skyscrapers since the 1960s.

[edit] Interpretation

Common interpretations of Islamic architecture include the following: The concept of Allah's infinite power is evoked by designs with repeating themes which suggest infinity. Human and animal forms are rarely depicted in decorative art as Allah's work is considered to be matchless. Foliage is a frequent motif but typically stylized or simplified for the same reason. Arabic Calligraphy is used to enhance the interior of a building by providing quotations from the Qur'an. Islamic architecture has been called the "architecture of the veil" because the beauty lies in the inner spaces (courtyards and rooms) which are not visible from the outside (street view). Furthermore, the use of grandiose forms such as large domes, towering minarets, and large courtyards are intended to convey power.

[edit] Architecture Forms and Styles of mosques and buildings in Muslim countries

[edit] Forms

Many forms of Islamic architecture have evolved in different regions of the Islamic world. Notable Islamic architectural types include the early Abbasid buildings, T-Type mosques, and the central-dome mosques of Anatolia. The oil-wealth of the 20th century drove a great deal of mosque construction using designs from leading modern architects.

Arab-plan or hypostyle mosques are the earliest type of mosques, pioneered under the Umayyad Dynasty. These mosques are square or rectangular in plan with an enclosed courtyard and a covered prayer hall. Historically, because of the warm Mediterranean and Middle Eastern climates, the courtyard served to accommodate the large number of worshipers during Friday prayers. Most early hypostyle mosques have flat roofs on top of prayer halls, necessitating the use of numerous columns and supports.[16] One of the most notable hypostyle mosques is the Mezquita in Córdoba, Spain, as the building is supported by over 850 columns.[17] Frequently, hypostyle mosques have outer arcades so that visitors can enjoy some shade. Arab-plan mosques were constructed mostly under the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties; subsequently, however, the simplicity of the Arab plan limited the opportunities for further development, and as a result, these mosques gradually fell out of popularity.[16]

The Ottomans introduced central dome mosques in the 15th century and have a large dome centered over the prayer hall. In addition to having one large dome at the center, there are often smaller domes that exist off-center over the prayer hall or throughout the rest of the mosque, where prayer is not performed.[18] This style was heavily influenced by the Byzantine religious architecture with its use of large central domes.[16]

[edit] Iwan

An iwan (Persian ايوان derived from Pahlavi word Bān meaning house) is defined as a vaulted hall or space, walled on three sides, with one end entirely open.

Iwans were a trademark of the Sassanid architecture of Persia, later finding their way into Islamic architecture. This transition reached its peak during the Seljuki era when iwans became established as a fundamental design unit in Islamic architecture. Typically, iwans open on to a central courtyard, and have been used in both public and residential architecture.

Iwan mosques are most notable for their domed chambers and iwans, which are vaulted spaces open out on one end. In iwan mosques, one or more iwans face a central courtyard that serves as the prayer hall. The style represents a borrowing from pre-Islamic Iranian architecture and has been used almost exclusively for mosques in Iran. Many iwan mosques are converted Zoroastrian fire temples where the courtyard was used to house the sacred fire.[16] Today, iwan mosques are seldom built.[18] A notable example of a more recent four iwan design is the King Saud Mosque in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, finished in 1987.

[edit] Sahn

Almost every mosque and traditionally all houses and buildings in areas of the Arab World contain a courtyard known as a sahn (Arabic صحن), which are surrounded on all sides by rooms and sometimes an arcade. Sahns usually feature a centrally positioned pool known as a howz.

If a sahn is in a mosque, it is used for performing ablutions. If a sahn is in a traditional house or private courtyard, it is used for aesthetics and to cool the summer heat.

[edit] Gardens

The Qur'an uses the garden as an analogy for paradise and Islam came to have a significant influence on garden design.

[edit] Arabesque

An element of Islamic art usually found decorating the walls of mosques and Muslim homes and buildings, the arabesque is an elaborate application of repeating geometric forms that often echo the forms of plants, shapes and sometimes animals (specifically birds). The choice of which geometric forms are to be used and how they are to be formatted is based upon the Islamic view of the world. To Muslims, these forms, taken together, constitute an infinite pattern that extends beyond the visible material world. To many in the Islamic world, they in fact symbolize the infinite, and therefore uncentralized, nature of the creation of the one God ("Allah" in Arabic). Furthermore, the Islamic Arabesque artist conveys a definite spirituality without the iconography of Christian art. Arabesque is used in mosques and building around the Muslim world, and it is a way of decorating using beautiful, embellishing and repetitive Islamic art instead of using pictures of humans and animals (which is forbidden Haram in Islam).

[edit] Calligraphy

Arabic calligraphy is associated with geometric Islamic art (the Arabesque) on the walls and ceilings of mosques as well as on the page. Contemporary artists in the Islamic world draw on the heritage of calligraphy to use calligraphic inscriptions or abstractions in their work.

Instead of recalling something related to the reality of the spoken word, calligraphy for the Muslim is a visible expression of spiritual concepts. Calligraphy has arguably become the most venerated form of Islamic art because it provides a link between the languages of the Muslims with the religion of Islam. The holy book of Islam, al-Qur'ān, has played a vital role in the development of the Arabic language, and by extension, calligraphy in the Arabic alphabet. Proverbs and complete passages from the Qur'an are still active sources for Islamic calligraphy.

[edit] Elements of Islamic style

Islamic architecture may be identified with the following design elements, which were inherited from the first mosque built byr hall (originally a feature of the Masjid al-Nabawi).

- Minarets or towers (these were originally used as torch-lit watchtowers, as seen in the Great Mosque of Damascus; hence the derivation of the word from the Arabic nur, meaning "light").

- A four-iwan plan, with three subordinate halls and one principal one that faces toward Mecca

- Mihrab or prayer niche on an inside wall indicating the direction to Mecca. This may have been derived from previous uses of niches for the setting of the torah scrolls in Jewish synagogues or the haikal of Coptic churches.

- Iwans to intermediate between different pavilions.

- The use of geometric shapes and repetitive art (arabesque).

- The use of muqarnas, a unique Arabic/Islamic space-enclosing system, for the decoration of domes, minarets and portals. Used at the Alhambra.(Compare mocárabe.) Modern muqarnas designs [2]

- The use of decorative Islamic calligraphy instead of pictures which were haram (forbidden) in mosque architecture. Note that in secular architecture, human and animal representation was indeed present.

- The use of bright color, if the style is Persian or Indian (Mughal); paler sandstone and grey stones are preferred among Arab buildings. Compare the Registan complex of Uzbekistan to the Al-Azhar University of Cairo.

- Focus both on the interior space of a building and the exterior[citation needed]

[edit] Differences between Islamic architecture and Persian architecture

Like this of other nations that became part of the Islamic realm, Persian Architecture is not to be confused with Islamic Architecture and refers broadly to architectural styles across the Islamic world. Islamic architecture, therefore, does not directly include reference to Persian styles prior to the rise of Islam. Persian architecture, like other nations', predates Islamic architecture and can be correctly understood as an important influence on overall Islamic architecture as well as a branch of Islamic architecture since the introduction of Islam in Persia. Islamic architecture can be classified according to chronology, geography, and building typology.

[edit] References

- ^ a b Copplestone, p.149

- ^ http://www.islamonline.net/servlet/Satellite?c=Article_C&cid=1158658332974&pagename=Zone-English-ArtCulture%2FACELayout A Tour of Architecture in Islamic Cities

- ^ Peter J. Lu and A. (2007). "Decagonal and Quasi-crystalline Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture" (PDF). Science 315: 1106–1110. doi:. PMID 17322056. http://www.physics.harvard.edu/~plu/publications/Science_315_1106_2007.pdf.

- ^ Supplemental figures [1]

- ^ Tonna (1990), pp.182-197

- ^ Grabar, O. (2006) p.87

- ^ Ettinghausen (2003), p.87

- ^ a b "Islam", The New Encyclopedia Britannica (2005)

- ^ Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. Cairo of the Mamluks : A History of Architecture and Its Culture. New York: Macmillan, 2008.

- ^ Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. Cairo of the Mamluks : A History of Architecture and Its Culture. New York: Macmillan, 2008.

- ^ Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. Cairo of the Mamluks : A History of Architecture and Its Culture. New York: Macmillan, 2008.

- ^ Cowen, Jill S. (July/August 1985). "Muslims in China: The Mosque". Saudi Aramco World. pp. 30-35. http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/198504/muslims.in.china-the.mosques.htm. Retrieved on 2006-04-08.

- ^ Saudi Aramco World, July/August 1985 , page 3035

- ^ Historical Society of Ghana. Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana, The Society, 1957, pp81

- ^ Davidson, Basil. The Lost Cities of Africa. Boston: Little Brown, 1959, pp86

- ^ a b c d Hillenbrand, R. "Masdjid. I. In the central Islamic lands". in P.J. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Encyclopaedia of Islam Online. Brill Academic Publishers. ISSN 1573-3912.

- ^ "Religious Architecture and Islamic Cultures". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. http://web.mit.edu/4.614/www/handout02.html. Retrieved on 2006-04-09.

- ^ a b "Vocabulary of Islamic Architecture". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. http://ocw.mit.edu/OcwWeb/Architecture/4-614Religious-Architecture-and-Islamic-CulturesFall2002/LectureNotes/detail/vocab-islam.htm#islam6. Retrieved on 2006-04-09.