History of science fiction

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Science Fiction |

|---|

| Books · Authors Films · Television Conventions |

The literary genre of science fiction is diverse and since there is little consensus of definition among scholars or devotees, its origin is an open question. Some offer works like the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh as the primal texts of science fiction. Others argue that science fiction began in the late Middle Ages,[1] or that science fiction became possible only with the Scientific Revolution, notably discoveries by Galileo and Newton in astronomy, physics and mathematics. Some place the origin with the gothic novel, particularly Mary Shelley's Frankenstein.

Science fiction developed and boomed in the 20th century, as the deep penetration of science and inventions into society created an interest in literature that explored technology's influence on people and society. Today, science fiction has significant influence on world culture and thought. It is represented in all varieties of ordinary and advanced media.

Contents |

[edit] Early science fiction

[edit] Early precursors

There have been attempts by various historians to claim an ancient history for the genre of science fiction. This claim is now a minority opinion, with the majority placing these works at best as examples of proto-science fiction.[citation needed] Lester del Rey has stated that the first work of science fiction was the first recorded work of literature, The Epic of Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh features a flood scene that in some ways resembles work of apocalyptic science fiction; however, it is probably better categorized as fantastic literature, as there is little of science or technology in it. Greek works with science fiction-like elements include - besides Lucian's True History - Aristophanes' The Clouds and The Birds, and Plato's descriptions of Atlantis. Early elements of science fiction are also found in ancient Indian epics such as the Ramayana, which had mythical Vimana flying machines that were able to fly within the Earth's atmosphere, and able to travel into space and travel submerged under water.

Works of fantastic literature from Ovid's Metamorphoses telling of Daedalus and Icarus to Beowulf and the Nibelungenlied to Dante's The Divine Comedy and Shakespeare's The Tempest have also been claimed to contain science fictional elements, with varying degrees of success. The Tempest contains one Renaissance prototype for the mad scientist story (the Faust legend is another), and it was adapted as the science fiction film Forbidden Planet.

L. Sprague de Camp and a number of other authors cite Lucian's 2nd century satirical True History about an interplanetary trip as an early, if not the earliest, example of science fiction or proto-science fiction.[2][3][4][5][6] The position of the English critic Kingsley Amis seems ambivalent. While he wrote that "It is hardly science-fiction, since it deliberately piles extravagance upon extravagance for comic effect",[citation needed] he implicitly acknowledged its SF character by comparing its plot to early 20th century space operas: "I will merely remark that the sprightliness and sophistication of True History make it read like a joke at the expense of nearly all early-modern science fiction, that written between, say, 1910 and 1940."[7] Typical science fiction themes and topoi in True History include:[3] travel to outer space, encounter with alien life-forms, including the experience of a first encounter event, interplanetary warfare and imperialism, colonization of planets, motif of giganticism, creatures as products of human technology (robot theme), worlds working by a set of alternate 'physical' laws and an explicit desire of the protagonist for exploration and adventure.

Several stories within the One Thousand and One Nights (Arabian Nights) also feature science fiction elements. One example is "The Adventures of Bulukiya", where the protagonist Bulukiya's quest for the herb of immortality leads him to explore the seas, journey to the Garden of Eden and to Jahannam, and travel across the cosmos to different worlds much larger than his own world, anticipating elements of galactic science fiction;[8] along the way, he encounters societies of jinns,[9] mermaids, talking serpents, talking trees, and other forms of life.[8] In "Abdullah the Fisherman and Abdullah the Merman", the protagonist gains the ability to breathe underwater and discovers an underwater submarine society that is portrayed as an inverted reflection of society on land, in that the underwater society follows a form of primitive communism where concepts like money and clothing do not exist. Other Arabian Nights tales deal with lost ancient technologies, advanced ancient civilizations that went astray, and catastrophes which overwhelmed them.[10] "The City of Brass" features a group of travellers on an archaeological expedition[11] across the Sahara to find an ancient lost city and attempt to recover a brass vessel that Solomon once used to trap a jinn,[12] and, along the way, encounter a mummified queen, petrified inhabitants,[13] life-like humanoid robots and automata, seductive marionettes dancing without strings,[14] and a brass horseman robot who directs the party towards the ancient city. "The Ebony Horse" features a robot[15] in the form of a flying mechanical horse controlled using keys that could fly into outer space and towards the Sun,[16] while the "Third Qalandar's Tale" also features a robot in the form of an uncanny boatman.[15] "The City of Brass" and "The Ebony Horse" can be considered early examples of proto-science fiction.[17][18] Other examples of early Arabic proto-science fiction include Al-Farabi's Opinions of the residents of a splendid city about a utopian society, Al-Qazwini's futuristic tale of Awaj bin Anfaq about a man who travelled to Earth from a distant planet, and certain Arabian Nights elements such as the flying carpet.[19]

The 10th century Japanese narrative, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, may also be considered proto-science fiction. The protagonist of the story, Kaguya-hime, is a princess from the Moon who is sent to Earth for safety during a celestial war, and is found and raised by a bamboo cutter in Japan. She is later taken back to the Moon by her real extraterrestrial family. A manuscript illustration depicts a round flying machine similar to to a flying saucer.[18]

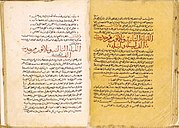

According to Roubi,[1] the final two chapters of the Arabic theological novel Fādil ibn Nātiq (known as Theologus Autodidactus in the West) by the Arabian polymath writer Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288) can be described as science fiction. The theological novel deals with various science fiction elements such as spontaneous generation, futurology, apocalyptic themes, eschatology, resurrection and the afterlife, but rather than giving supernatural or mythological explanations for these events, Ibn al-Nafis attempted to explain these plot elements using his own extensive scientific knowledge in anatomy, biology, physiology, astronomy, cosmology and geology. For example, it was through this novel that Ibn al-Nafis introduces his scientific theory of metabolism,[1] and he makes references to his own scientific discovery of the pulmonary circulation in order to explain bodily resurrection.[20] The novel was later translated into English as Theologus Autodidactus in the early 20th century.

[edit] European proto-science fiction

Literature that resembles modern science fiction emerged in Europe from the 16th century. The discoveries in the sciences and the dawning of the Enlightenment inspired literature informed by these advances. One of the earliest instances is the superior country imagined in Thomas More's 1516 novel Utopia. More's name for a perfect world would be borrowed by many later science fiction writers, and the Utopia motif is a common one in science fiction. It is notable that More and Francis Bacon, leading humanist and philosopher of science, wrote works of proto-science fiction. Bacon's fantasy The New Atlantis was published in 1627.

The Age of Reason followed scientific developments that gave speculative writers ideas for their stories. Imaginary voyages to the moon in the 17th century, first in Johannes Kepler's Somnium (The Dream, 1634), and then in Cyrano de Bergerac's Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon (1656).[21] Space travel also figures prominently in Voltaire's Micromégas (1752), which is also notable for the suggestion that people of other worlds may be in some ways more advanced than those of earth.

Other early works of significance include the alternate world found in the Arctic by a young noblewoman in Margaret Cavendish's 1666 novel, The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing-World, the account of life in the future in Louis-Sébastien Mercier's L'An 2440, and the descriptions of alien cultures in Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726) and in Ludvig Holberg's Niels Klim's Underground Travels, an early example of the Hollow Earth genre. In 1733, Samuel Madden wrote Memoirs Of the Twentieth Century, in which the narrator in 1728 is given a series of state documents from 1997–1998 by his guardian angel, a plot device which is reminiscent of later time travel novels although the story does not explain how the angel obtained these documents.

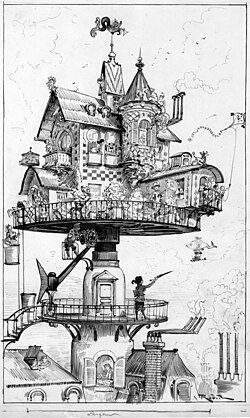

Also worthy of note are Simon Tyssot de Patot's Voyages et Aventures de Jacques Massé (1710), which features a Lost World, La Vie, Les Aventures et Le Voyage de Groenland du Révérend Père Cordelier Pierre de Mésange (1720), which features a Hollow Earth, and Nicolas-Edmé Restif de la Bretonne's La Découverte Australe par un Homme Volant (1781) notorious for his prophetic inventions.

Most notable of all is Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, first published in 1818.[22] In his book Billion Year Spree, Brian Aldiss claims Frankenstein represents "the first seminal work to which the label SF can be logically attached". It is also the first of the "mad scientist" subgenre. Although normally associated with the gothic horror genre, the novel introduces science fiction themes such as the use of technology for achievements beyond the scope of science at the time, and the alien as antagonist, furnishing a view of the human condition from an outside perspective. Aldiss argues that science fiction in general derives its conventions from the gothic novel. Mary Shelley's short story "Roger Dodsworth: The Reanimated Englishman" (1826) sees a man frozen in ice revived in the present day, incorporating the now common science fiction theme of cryonics whilst also exemplifying Shelley's use of science as a conceit to drive her stories. Another futuristic Shelley novel, The Last Man, is also often cited as the first true science fiction novel.[22]

In 1835 Edgar Allan Poe published a short story, "The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall" in which a flight to the moon in a balloon is described. It has an account of the launch, the construction of the cabin, descriptions of strata and many more science-like aspects.[23] In addition to Poe's account the story written in 1813 by the Dutch Willem Bilderdijk is remarkable. In his novel Kort verhaal van eene aanmerkelijke luchtreis en nieuwe planeetontdekking (Short account of a remarkable journey into the skies and discovery of a new planet) Bilderdijk tells of a European somewhat stranded in an Arabic country where he boasts he is able to build a balloon that can lift people and let them fly through the air. The gasses used turn out to be far more powerful than expected and after a while he lands on a planet positioned between earth and moon. The writer uses the story to portray an overview of scientific knowledge concerning the moon in all sorts of aspects the traveller to that place would encounter. Quite a few similarities can be found in the story Poe published some twenty years later.

Somehow influenced by the scientific theories of 19th century, but most certainly by the idea of human progress, Victor Hugo wrote in The Legend of the Centuries (1859) a long poem in two part that can be viewed like a dystopia/utopia fiction, called Twentieth century. It shows in a first scene the body of a broken huge ship, the greatest product of the prideful and foolish mankind that called it Leviathan, wandering in a desert world where the winds blow and the anger of the wounded Nature is; humanity, finally reunited and pacified, has gone toward the stars in a starship, to look for and to bring « liberty into the light ».

Other notable proto-science fiction authors and works of the early 19th century include:

- Jean-Baptiste Cousin de Grainville's Le Dernier Homme (1805) (The Last Man).

- Historian Félix Bodin's Le Roman de l'Avenir (1834) and Emile Souvestre's Le Monde Tel Qu'il Sera (1846), two novels which try to predict what the next century will be like.

- Jane C. Loudon's The Mummy!: A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century (1836), in which Cheops is revived by scientific means into a world in political crisis, where technology has advanced to gas-flame jewelry and houses that migrate on rails, &c.

- Louis Geoffroy's Napoleon et la Conquête du Monde (1836), an alternate history of a world conquered by Napoleon.

- C.I. Defontenay's Star ou Psi de Cassiopée (1854), an Olaf Stapledon-like chronicle of an alien world and civilization.

- Astronomer Camille Flammarion's La Pluralité des Mondes Habités (1862) which speculated on extraterrestrial life.

- Edward Bulwer-Lytton's The Coming Race (1871), a novel where the main character discovers a highly evolved subterranean civilization.

[edit] Verne and Wells

The European brand of science fiction proper began later in the 19th century with the scientific romances of Jules Verne and the science-oriented novels of social criticism of H. G. Wells.[24]

Verne's adventure stories, notably Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864), From the Earth to the Moon (1865), and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1869) mixed daring romantic adventure with technology that was either up to the minute or logically extrapolated into the future. They were tremendous commercial successes and established that an author could make a career out of such whimsical material. L. Sprague de Camp calls Verne "the world's first full-time science fiction novelist."

Wells's stories, on the other hand, use science fiction devices to make didactic points about his society. In The Time Machine (1895), for example, the technical details of the machine are glossed over quickly so that the Time Traveller can tell a story that criticizes the stratification of English society. On the other hand, Wells demonstrates an awareness of space-time relationships soon to become mainstream with Einstein. The story also uses Darwinian evolution (as would be expected in a former student of Darwin's champion, Huxley), and shows an awareness, and criticism, of Marxism. In The War of the Worlds (1898), the Martians' technology is not explained as it would have been in a Verne story, and the story is resolved by a deus ex machina.

The differences between Verne and Wells highlight a tension that would exist in science fiction throughout its history. The question of whether to present realistic technology or to focus on characters and ideas has been ever-present, as has the question of whether to tell an exciting story or make a didactic point.

Wells and Verne had quite a few rivals in early science fiction. Short stories and novelettes with themes of fantastic imagining appeared in journals throughout the late 19th century and many of these employed scientific ideas as the springboard to the imagination. Erewhon is a novel by Samuel Butler published in 1872 and dealing with the concept that machines could one day become sentient and supplant the human race. Although better known for Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle also wrote early science fiction, as did Rudyard Kipling, Jagadananda Roy and Begum Roquia Sakhawat Hussain (see Bangla science fiction). Utopian feminist science fiction also began at around this time, with Begum Roquia Sakhawat Hussain's Sultana's Dream and Charlotte Perkins Gilman' Herland being the earliest examples.

Wells and Verne both had an international readership and influenced writers in America, especially. Soon a home-grown American science fiction was thriving. European writers found more readers by selling to the American market and writing in an Americanised style.

[edit] American proto-science fiction

In the last decades of the 19th century, works of science fiction for adults and children were numerous in America, though it was not yet given the name "science fiction."

There were science-fiction elements in the stories of Nathaniel Hawthorne and Fitz-James O'Brien. Edgar Allan Poe is often mentioned with Verne and Wells as the founders of science fiction. A number of his short stories, and the novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket are science fictional. An 1827 satiric novel by philosopher George Tucker A Voyage to the Moon is sometimes cited as the first American science fiction novel.

One of the most successful works of early American science fiction was the second-best selling novel in the U.S. in the 19th century: Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward (1888), its effects extending far beyond the field of literature. Looking Backward extrapolates a future society based on observation of the current society.

Mark Twain explored themes of science in his novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court. By means of "transmigration of souls", "transposition of epochs -- and bodies" Twain's Yankee is transported back in time and his knowledge of 19th century technology with him. Written in 1889, A Connecticut Yankee seems to predict the events of World War I, when Europe's old ideas of chivalry in warfare were shattered by new weapons and tactics.

American author L. Frank Baum's series of 14 books (1900-1920) based in his outlandish Land of Oz setting, contained depictions of strange weapons (Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, Glinda of Oz), mechanical men (Tik-Tok of Oz) and a bevy of not-yet-realized technological inventions and devices including perhaps the first literary appearance of handheld wireless communicators (Tik-Tok of Oz).

Jack London wrote several science fiction stories, including The Red One (a story involving extraterrestrials), The Iron Heel (set in the future from London's point of view) and The Unparalleled Invasion (a story involving future germ warfare and ethnic cleansing). He also wrote a story about invisibility and a story about an irresistible energy weapon. These stories began to change the features of science fiction.

Edward Everett Hale wrote The Brick Moon, a Verne-inspired novel notable as the first work to describe an artificial satellite. Written in much the same style as his other work, it employs pseudojournalistic realism to tell an adventure story with little basis in reality.

Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875–1950) began writing science fiction for pulp magazines just before World War I, getting his first story Under the Moons of Mars published in 1912. He continued to publish adventure stories, many of them science fiction, throughout the rest of his life. The pulps published adventure stories of all kinds. Science fiction stories had to fit in alongside murder mysteries, horror, fantasy and Edgar Rice Burroughs' own Tarzan.

[edit] Early 20th century

The next great science fiction writers after H. G. Wells were Olaf Stapledon (1886 to 1950), whose four major works Last and First Men (1930), Odd John (1935), Star Maker (1937), and Sirius (1940), introduced a myriad of ideas that writers have since adopted, and J.-H. Rosny aîné, born in Belgium, the father of "modern" French science fiction, a writer also comparable to H. G. Wells, who wrote the classic Les Xipehuz (1887) and La Mort de la Terre (1910). However, the Twenties and Thirties would see the genre represented in a new format.

[edit] Birth of the pulps

The development of American science fiction as a self-conscious genre dates in part from 1926, when Hugo Gernsback founded Amazing Stories magazine, which was devoted exclusively to science fiction stories.[25] Though science fiction magazines had been published in Sweden and Germany before, Amazing Stories was the first English language magazine to solely publish science fiction. Since he is notable for having chosen the variant term scientifiction to describe this incipient genre, the stage in the genre's development, his name and the term "scientifiction" are often thought to be inextricably linked. Though Gernsback encouraged stories featuring scientific realism to educate his readers about scientific principles, such stories shared the pages with exciting stories with little basis in reality. Published in this and other pulp magazines with great and growing success, such scientifiction stories were not viewed as serious literature but as sensationalism. Nevertheless, a magazine devoted entirely to science fiction was a great boost to the public awareness of the scientific speculation story.

Amazing Stories competed with other pulp magazines, including Weird Tales, which primarily published fantasy stories, Astounding Stories, and Wonder throughout the 1930s.

Fritz Lang's movie Metropolis (1927), in which the first cinematic humanoid robot was seen, and the Italian Futurists' love of machines are indicative of both the hopes and fears of the world between the big European wars. Metropolis was an extremely successful film and its art-deco inspired aesthetic became the guiding aesthetic of the science fiction pulps for some time.

[edit] Modernist writing

Writers attempted to respond to the new world in the post-World War I era. In the 1920s and 30s writers entirely unconnected with science fiction were exploring new ways of telling a story and new ways of treating time, space and experience in the narrative form. The posthumously published works of Franz Kafka (who died in 1924) and the works of modernist writers such as James Joyce, T. S. Eliot, Virginia Woolf and others featured stories in which time and individual identity could be expanded, contracted, looped and otherwise distorted. While this work was unconnected to science fiction as a genre, it did deal with the impact of modernity (technology, science, and change) upon people's lives, and decades later, during the New Wave movement, some modernist literary techniques entered science fiction.

Czech playwright Karel Čapek's plays The Makropulos Affair, R.U.R., The Life of the Insects, and the novel War with the Newts were modernist literature which invented important science fiction motifs. R.U.R. in particular is noted for introducing the word robot to the world's vocabulary.

A strong theme in modernist writing was alienation, the making strange of familiar surroundings so that settings and behaviour usually regarded as "normal" are seen as though they were the seemingly bizarre practices of an alien culture. The audience of modernist plays or the readership of modern novels is often led to question everything.

At the same time, a tradition of more literary science fiction novels, treating with a dissonance between perceived Utopian conditions and the full expression of human desires, began to develop: the dystopian novel. For some time, the science fictional elements of these works were ignored by mainstream literary critics, though they owe a much greater debt to the science fiction genre than the modernists do. Sincerely Utopian writing, including much of Wells, has also deeply influenced science fiction, beginning with Hugo Gernsback's Ralph 124C 41+. Yevgeny Zamyatin's 1920 novel We depicts a totalitarian attempt to create a utopia that results in a dystopic state where free will is lost. Aldous Huxley bridged the gap between the literary establishment and the world of science fiction with Brave New World (1932), an ironic portrait of a stable and ostensibly happy society built by human mastery of genetic manipulation.

In the late 1930s, John W. Campbell became editor of Astounding Science Fiction, and a critical mass of new writers emerged in New York City in a group called the Futurians, including Isaac Asimov, Damon Knight, Donald A. Wollheim, Frederik Pohl, James Blish, Judith Merril, and others.[26] Other important writers during this period included Robert A. Heinlein, Arthur C. Clarke, and A. E. van Vogt. Campbell's tenure at Astounding is considered to be the beginning of the Golden Age of science fiction, characterized by hard science fiction stories celebrating scientific achievement and progress.[25] This lasted until postwar technological advances, new magazines like Galaxy under Pohl as editor, and a new generation of writers began writing stories outside the Campbell mode.

George Orwell wrote perhaps the most highly regarded of these literary dystopias, Nineteen Eighty-Four, in 1948. He envisions a technologically-governed totalitarian regime that dominates society through total information control. Zamyatin's We is recognized as an influence on both Huxley and Orwell; Orwell published a book review of the We shortly after it was first published in English, several years before writing 1984.

Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, Ursula LeGuin's The Dispossessed, much of Kurt Vonnegut's writing, and many other works of later science fiction continue this dialogue between utopia and dystopia.

[edit] Public mythology

Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre produced a radio version of The War of the Worlds which, famously, panicked large numbers of people who believed the program to be a real newscast.[27] The idea of visitors or invaders from outer space became firmly part of the public mythology.

During World War II pilots speculated on the possible origins of the Foo fighters they saw around them in the air. The German flying bombs, V1s and V2s added to the growing wonder about the future of space travel. Jet planes and the atom bomb were developed. When a story of a flying saucer crash was circulated from Roswell, New Mexico in 1947, science fiction had become folklore.

[edit] The Golden Age

The period of the 1940s and 1950s is often referred to as the Golden Age of Science Fiction.

[edit] Astounding Magazine

With the emergence in 1937 of a demanding editor, John W. Campbell, Jr., at Astounding Science Fiction, and with the publication of stories and novels by such writers as Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, and Robert A. Heinlein, science fiction began to gain status as serious fiction.

Campbell exercised an extraordinary influence over the work of his stable of writers, thus shaping the direction of science fiction. Asimov wrote, "We were extensions of himself; we were his literary clones." Under Campbell's direction, the years from 1938–1950 would become known as the "Golden Age of science fiction",[25] though Asimov points out that the term Golden Age has been used more loosely to refer to other periods in science fiction's history.

Campbell's guidance to his writers included his famous dictum, "Write me a creature that thinks as well as a man, or better than a man, but not like a man." He emphasized a higher quality of writing than editors before him, giving special attention to developing the group of young writers who attached themselves to him.

Ventures into the genre by writers who were not devoted exclusively to science fiction also added respectability. Magazine covers of bug-eyed monsters and scantily-clad women, however, preserved the image of a sensational genre appealing only to adolescents. There was naturally a public desire for sensation, a desire of people to be taken out of their dull lives to the worlds of space travel and adventure.

An interesting footnote to Campbell's regime is his contribution to the rise of L. Ron Hubbard's religion Scientology. Hubbard was considered a promising science fiction writer and a protege of Campbell, who published Hubbard's first articles about Dianetics and his new religion. As Campbell's reign as editor of Astounding progressed, Campbell gave more attention to ideas like Hubbard's, writing editorials in support of Dianetics. Though Astounding continued to have a loyal fanbase, readers started turning to other magazines to find science fiction stories.

[edit] The Golden Age in other media

With the new source material provided by the Golden Age writers, advances in special effects, and a public desire for material that treated with the advances in technology of the time, all the elements were in place to create significant works of science fiction film.

As a result, science fiction film came into its own in the 1950s, producing films like Destination Moon, Them!, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Forbidden Planet, and many others. Many of these movies were based on stories by Campbell's writers. The Thing was adapted from a Campbell story, Them and Invasion of the Body Snatchers were based on Jack Finney novels, Destination Moon on a Heinlein novel, and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms was derived from a Ray Bradbury short story. John Wyndham's cosy catastrophes, including The Day of the Triffids and The Kraken Wakes, provided important source material as well.

At the same time, science fiction began to appear on a new medium- the television. In the 1953 The Quatermass Experiment was shown on British television, the first significant science fiction show.[citation needed] In the United States, science fiction heroes like Captain Video, Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers were shown, programs that more closely resembled pre-Campbellian science fiction.

[edit] End of the Golden Age

Seeking greater freedom of expression, writers started to publish their articles in other magazines, including The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, If, a resurrected Amazing Stories, and most notably, Galaxy.

Under editors H.L. Gold and then Frederik Pohl, Galaxy stressed a more literary form of science fiction that took cues from more mainstream literature. It was less insistent on scientific plausibility than Campbell's Astounding. The rise of Galaxy signaled the end of Golden Age science fiction, though most of the Golden Age writers were able to adapt to the changes in the genre and keep writing. Some, however, moved to other fields. Isaac Asimov and several others began to write scientific fact almost exclusively.

[edit] The New Wave and its aftermath

[edit] The Beat Generation

Samuel Beckett's modernistic writings The Unnamable and Waiting for Godot were influential upon writing in the 1950s. In the former all sense of place and time are dispensed with and all that remains is a voice poised between the urge to continue existing and the urge to find silence and oblivion. In the latter, time and the meaning of cause and effect are played with to great effect. Beckett's influence could be felt on science fiction, which moved toward more serious reflection on being.

William S. Burroughs (1914–1997) was the writer who finally brought science fiction together with the modernist trend in literature. With the help of Jack Kerouac Burroughs published Naked Lunch, the first of a series of novels employing a semi-dadaistic technique called the Cut-up and modernistic deconstructions of conventional society, pulling away the mask of normality to reveal horrors beneath. Burroughs showed visions of society as a conspiracy of aliens, monsters, police states, drug dealers and alternate levels of reality. The linguistics of science fiction merged with the experiments of modernism in a beat generation nightmare.

[edit] The New Wave

In 1960, British novelist Kingsley Amis published New Maps of Hell, a literary history and examination of the field of science fiction. This serious attention from a mainstream, acceptable writer did a great deal of good, eventually, for the reputation of science fiction.

In 1962, Academy Award winning Indian writer and film-maker Satyajit Ray wrote a Bangla science fiction story entitled Bankubabur Bandhu (Banku Babu's Friend), also known as The Alien. What differentiated Bankubabur Bandhu from previous science fiction was the portrayal of an alien from outer space as a kind and playful being, invested with magical powers and capable of interacting with children, in contrast to earlier science fiction works which portrayed aliens as dangerous creatures.[28][29][30]

Another major milestone was the publication, in 1965, of Frank Herbert's Dune, a dense, complex, and detailed work of fiction featuring political intrigue in a future galaxy, strange and mystical religious beliefs, and the eco-system of the desert planet Arrakis. Another was the emergence of the work of Roger Zelazny, whose novels such as Lord of Light and his famous The Chronicles of Amber showed that the lines between science-fiction, fantasy, religion, and social commentary could be very fine.

Also in 1965 French director Jean-Luc Godard's film Alphaville used the medium of dystopian and apocalyptic science fiction to explore language and society.

In Britain, the 1960s generation of writers, dubbed "The New Wave", were experimenting with different forms of science fiction,[21] stretching the genre towards surrealism, psychological drama and mainstream currents. The 60s New Wave was centred around the writing in the magazine New Worlds after Michael Moorcock assumed editorial control in 1963. William Burroughs was a big influence. The writers of the New Wave also believed themselves to be building on the legacy of the French New Wave artistic movement. Though the New Wave was largely a British movement, there were parallel developments taking place in American science fiction at the same time. The relation of the British New Wave to American science fiction was made clear by Harlan Ellison's original anthology Dangerous Visions, which presented science fiction writers, both American and British, writing stories that pushed the boundaries of what was acceptable in a science fiction magazine. Isaac Asimov, writing an introduction to the anthology, labeled it the Second Revolution, after the first revolution that produced the Golden Age.

The New Wave and their contemporaries placed a greater emphasis on style and a more highbrow form of a storytelling. They also sought controversy in subjects older science fiction writers had avoided. For the first time sexuality, which Kingsley Amis had complained was nearly ignored in science fiction, was given serious consideration by writers like Samuel Delany, Norman Spinrad, and Theodore Sturgeon. Contemporary political issues were also given voice, as John Brunner and J.G. Ballard wrote cautionary tales about a ruined environment.

Asimov noted that the Second Revolution was far less clear cut than the first, attributing this to the development of the anthology, which made older stories more prominent. But a number of Golden Age writers changed their style as the New Wave hit. Robert A. Heinlein switched from his Campbellian Future History stories to stylistically adventuresome, sexually open works of fiction, notably Stranger in a Strange Land and The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress. Isaac Asimov wrote the New Wave-ish The Gods Themselves. Many others also continued successfully as styles changed.

Science fiction films took inspiration from the changes in the genre. Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, Dr. Strangelove, and A Clockwork Orange gave visual form to the genre's new dependence on style.

Ursula LeGuin, working off small modifications to an imagined society, extrapolated science fictional visions that were anthropological rather than technical.[31] Philip K. Dick explored the metaphysics of the mind in a series of novels and stories that rarely seemed dependent on their science fictional content. LeGuin, Dick, and others like them became associated with the concept of soft science fiction more than with the New Wave.

Soft science fiction was contrasted to the notion of hard science fiction. Though scientific plausibility had been a central tenet of the genre since Gernsback, writers like Larry Niven and Poul Anderson gave hard science fiction new life, crafting stories with a more sophisticated writing style and more deeply characterized heroes, while preserving a high level of scientific sophistication.[32]

[edit] Science fiction in the 1980s

[edit] Cyberpunk

By the early 1980s, the New Wave had faded out as an important presence in the science fiction landscape. As new personal computing technologies became an integral part of society, science fiction writers felt the urge to make statements about its influence on the cultural and political landscape. Drawing on the work of the New Wave, the Cyberpunk movement developed in the early 80s. Though it placed the same influence on style that the New Wave did, it developed its own unique style, typically focusing on the 'punks' of their imagined future underworld. Cyberpunk authors like William Gibson turned away from the traditional optimism and support for progress of traditional science fiction.[33] William Gibson's Neuromancer, published in 1984 announced the cyberpunk movement to the larger literary world and was a tremendous commercial success. Other key writers in the movement included Bruce Sterling, John Shirley, and later Neal Stephenson. Though Cyberpunk would later be cross-pollinated with other styles of science-fiction, there seemed to be some notion of ideological purity in the beginning. John Shirley compared the Cyberpunk movement to a tribe.[34]

During the 1980s, a large number of cyberpunk manga and anime works were produced in Japan, the most notable being the 1982 manga Akira and its 1988 anime film adaptation, the 1985 anime Megazone 23, and the 1989 manga Ghost in the Shell which was also adapted into an anime film in 1995.

[edit] New space opera

The trend toward gritty, near-future stories represented by cyberpunk was countered by a revival and renewal of the tradition of space opera: stories set in the medium to far future and featuring interstellar civilizations, exotic technologies, and large-scale conflicts and natural events. Though such stories had never entirely disappeared from the field--Poul Anderson and Gordon R. Dickson, for example, had been writing space adventures consistently since the 1950s and Larry Niven since the 1960s. Star Wars helped spark a new interest in space opera.[35] But in the 1980s the old tradition was given a boost by such series as David Brin's Uplift Saga, C. J. Cherryh's Alliance-Union universe,[36] and the Ender novels of Orson Scott Card.

Throughout the decade, established writers continued to explore this territory: Greg Benford and Poul Anderson expanded on earlier work, Arthur C. Clarke added to his Rama series, and Isaac Asimov produced more Foundation novels. Emerging writers also offered large-scale interstellar adventures, for example, Greg Bear's Eon (1985), Iain M. Banks's Consider Phlebas (1987), Paul J. McAuley's 400 Billion Stars (1988), Bruce Sterling's Schismatrix (1985), and Michael Swanwick's Vacuum Flowers (1987).

While cyberpunk maintained a high profile through the 1980s, this new-generation space opera received more acclaim from the mainstream science fiction community. Though Gibson won both the Nebula Award and Hugo Award for Neuromancer, the majority of the winners of these awards from the 1980s onward could be classified as space opera (see Hartwell and Cramer, cited below).

The term "New Space Opera" finally emerged as a description of a body of work that had started to appear in the 1990s from UK and Australian writers such as Neal Asher, Stephen Baxter, Peter F. Hamilton, Ken MacLeod, Richard K. Morgan, Alastair Reynolds, Charles Stross, and the team of Sean Williams and Shane Dix. These writers were seen to be pushing the already-large envelope of space opera, integrating the latest science fiction ideas and motifs (nanotechnology, artificial intelligence, personality uploading, radical bodily transformations, cutting-edge physics and cosmology). American writers whose work has followed the same path include Wil McCarthy, Linda Nagata, Robert Reed, Dan Simmons, Vernor Vinge, Scott Westerfeld, Walter Jon Williams, and George Zebrowski.

The space opera trend also became popular in Japan, where a large number of manga and anime space operas were produced in the 1980s, the most notable being the Gundam and Macross series, as well as the theatrical version of the earlier Space Battleship Yamato (1973).

Locus magazine devoted part its August 2003 issue to old and new space opera, and David G. Hartwell and Kathryn Cramer have outlined a history of space opera that places the new works in context in "How Shit Became Shinola: Definition and Redefinition of Space Opera" (2003).[37]

[edit] Contemporary science fiction and its future

Contemporary science fiction has been marked by the spread of cyberpunk to other parts of the marketplace of ideas. No longer is cyberpunk a ghettoized tribe within science fiction, but an integral part of the field whose interactions with other parts have been the primary theme of science fiction at the turn of the century.

Notably, cyberpunk has influenced film, in works such as Johnny Mnemonic and The Matrix series, in anime such as Akira and Ghost in the Shell, and the emerging medium of computer and video games, with the critically acclaimed Deus Ex and Metal Gear series. This entrance of cyberpunk into mainstream culture has led to the introduction of cyberpunk's stylistic motifs to the masses, particularly the cyberpunk fashion style.

Emerging themes in the 1990s included environmental issues, the implications of the global Internet and the expanding information universe, questions about biotechnology and nanotechnology, as well as a post-Cold War interest in post-scarcity societies; Neal Stephenson's The Diamond Age comprehensively explores these themes. Lois McMaster Bujold's Vorkosigan novels brought the character-driven story back into prominence.[38]

The cyberpunk reliance on near-future science fiction has deepened. In William Gibson's 2003 novel, Pattern Recognition, the story is a cyberpunk story told in the present, the ultimate limit of the near-future extrapolation.

Cyberpunk's ideas have spread in other directions, though. Space opera writers have written work featuring cyberpunk motifs, including David Brin's Kiln People and Ken MacLeod's Fall Revolution series. This merging of the two disparate threads of science fiction in the 1980s has produced an extrapolational literature in contrast to those technological stories told in the present.

John Clute writes that science fiction at the turn of the century can be understood in two ways: "a vision of the triumph of science fiction as a genre and as a series of outstanding texts which figured to our gaze the significant futures that, during those years, came to pass... [or]... indecipherable from the world during those years... fatally indistinguishable from the world it attempted to adumbrate, to signify."

[edit] Contemporary SF on Television

The television series Star Trek: The Next Generation began a torrent of new science fiction shows, of which Babylon 5 was among the most highly acclaimed in the decade.[39][40] A general concern about the rapid pace of technological change crystallized around the concept of the technological singularity, popularized by Vernor Vinge's novel Marooned in Realtime and then taken up by other authors. Television shows like Buffy the Vampire Slayer and movies like The Lord of the Rings created new interest in all the speculative genres in films, television, computer games, and books.

[edit] Notes

- ^ a b c Dr. Abu Shadi Al-Roubi (1982), "Ibn al-Nafis as a philosopher", Symposium on Ibn al-Nafis, Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait (cf. Ibnul-Nafees As a Philosopher, Encyclopedia of Islamic World [1])

- ^ Grewell, Greg: “Colonizing the Universe: Science Fictions Then, Now, and in the (Imagined) Future”, Rocky Mountain Review of Language and Literature, Vol. 55, No. 2 (2001), pp. 25-47 (30f.)

- ^ a b Fredericks, S.C.: “Lucian's True History as SF”, Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 3, No. 1 (March 1976), pp. 49-60

- ^ Swanson, Roy Arthur: “The True, the False, and the Truly False: Lucian’s Philosophical Science Fiction”, Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Nov. 1976), pp. 227-239

- ^ Georgiadou, Aristoula & Larmour, David H.J.: “Lucian's Science Fiction Novel True Histories. Interpretation and Commentary“, Mnemosyne Supplement 179, Leiden 1998, ISBN 9004106677, Introduction

- ^ Gunn, James E.: “The New Encyclopedia of Science Fiction”, Publisher: Viking 1988, ISBN 9780670810413, p.249. Gunn calls the novel "proto-science fiction".

- ^ Kingsley, Amis: "New Maps of Hell: A Survey of Science Fiction", New York 1960, p.28

- ^ a b Irwin, Robert (2003), The Arabian Nights: A Companion, Tauris Parke Paperbacks, p. 209, ISBN 1860649831

- ^ Irwin, Robert (2003), The Arabian Nights: A Companion, Tauris Parke Paperbacks, p. 204, ISBN 1860649831

- ^ Irwin, Robert (2003), The Arabian Nights: A Companion, Tauris Parke Paperbacks, pp. 211–2, ISBN 1860649831

- ^ Hamori, Andras (1971), "An Allegory from the Arabian Nights: The City of Brass", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies (Cambridge University Press) 34 (1): 9–19 [9]

- ^ Pinault, David (1992), Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights, Brill Publishers, pp. 148–9 & 217–9, ISBN 9004095306

- ^ Irwin, Robert (2003), The Arabian Nights: A Companion, Tauris Parke Paperbacks, p. 213, ISBN 1860649831

- ^ Hamori, Andras (1971), "An Allegory from the Arabian Nights: The City of Brass", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies (Cambridge University Press) 34 (1): 9–19 [12–3]

- ^ a b Pinault, David (1992), Story-Telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights, Brill Publishers, pp. 10–1, ISBN 9004095306

- ^ Geraldine McCaughrean, Rosamund Fowler (1999), One Thousand and One Arabian Nights, Oxford University Press, pp. 247–51, ISBN 0192750135

- ^ Academic Literature, Islam and Science Fiction

- ^ a b Richardson, Matthew (2001), The Halstead Treasury of Ancient Science Fiction, Rushcutters Bay, New South Wales: Halstead Press, ISBN 1875684646 (cf. "Once Upon a Time", Emerald City (85), September 2002, http://www.emcit.com/emcit085.shtml#Once, retrieved on 2008-09-17)

- ^ Achmed A. W. Khammas, Science Fiction in Arabic Literature

- ^ Fancy, Nahyan A. G. (2006), "Pulmonary Transit and Bodily Resurrection: The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in the Works of Ibn al-Nafīs (d. 1288)", Electronic Theses and Dissertations (University of Notre Dame): 232–3, http://etd.nd.edu/ETD-db/theses/available/etd-11292006-152615

- ^ a b "Science Fiction". Encyclopedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-235714/science-fiction. Retrieved on 2007-01-17.

- ^ a b John Clute and Peter Nicholls (1993). "Mary W. Shelley". Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Orbit/Time Warner Book Group UK. http://www.sfhomeworld.org/exhibits/homeworld/scifi_hof.asp?articleID=62. Retrieved on 2007-01-17.

- ^ Poe, Edgar Allan. The Works of Edgar Allan Poe, Volume 1, "The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Pfaal". http://www.worldwideschool.org/library/books/lit/horror/TheWorksofEdgarAllenPoeVolume1/chap3.html. Retrieved on 2007-01-17.

- ^ "Science Fiction". Encarta Online Encyclopedia. Microsoft. 2006. http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761563123_2/Science_Fiction.html. Retrieved on 2007-01-17.

- ^ a b c Agatha Taormina (2005-01-19). "A History of Science Fiction". Northern Virginia Community College. http://www.nvcc.edu/home/ataormina/scifi/history/. Retrieved on 2007-01-16.

- ^ Resnick, Mike (1997). "The Literature of Fandom". Mimosa (#21). http://jophan.org/mimosa/m21/resnick.htm. Retrieved on 2007-01-17.

- ^ "War of the Worlds, Orson Welles, And The Invasion from Mars". http://www.transparencynow.com/welles.htm. Retrieved on 2007-05-28.

- ^ *Neumann P. "Biography for Satyajit Ray". Internet Movie Database Inc. http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0006249/bio. Retrieved on 2006-04-29.

- ^ Newman J (2001-09-17). "Satyajit Ray Collection receives Packard grant and lecture endowment". UC Santa Cruz Currents online. http://www.ucsc.edu/currents/01-02/09-17/ray.html. Retrieved on 2006-04-29.

- ^ "The Unmade Ray". Satyajit Ray Society. http://www.worldofray.com/raysfilmography/unmaderay.aspx. Retrieved on 2006-11-04.

- ^ Browning, Tonya (1993). A brief historical survey of women writers of science fiction. University of Texas in Austin. http://www.cwrl.utexas.edu/~tonya/Tonya/sf/history.html. Retrieved on 2007-01-19.

- ^ "SF TIMELINE 1960–1970". Magic Dragon Multimedia. 2003-12-24. http://www.magicdragon.com/UltimateSF/timeline1970.html. Retrieved on 2007-01-17.

- ^ Philip Hayward (1993). Future Visions: New Technologies of the Screen. British Film Institute. pp. 180–204. http://www.stanford.edu/class/history34q/readings/Cyberspace/HaywardSituatingCyberspace.html. Retrieved on 2007-01-17.

- ^ Cadigan, Pat. The Ultimate Cyberpunk iBooks, 2002.

- ^ Allen Varney (2004-01-04). "Exploding Worlds!". http://www.allenvarney.com/av_space2.html. Retrieved on 2007-01-17.

- ^ Vera Nazarian (2005-05-21). "Intriguing Links to Fabulous People and Places...". http://www.sff.net/people/vera.nazarian/links.htp. Retrieved on 2007-01-30.

- ^ "How Shit Became Shinola: Definition and Redefinition of Space Opera (2003)". http://www.sfrevu.com/ISSUES/2003/0308/Space%20Opera%20Redefined/Review.htm. Retrieved on 2007-05-28.

- ^ "Shards of Honor". NESFA Press. 2004-05-10. http://www.nesfa.org/press/Books/Bujold-2.htm. Retrieved on 2007-01-17.

- ^ David Richardson (1997-07). "72139759120570275Dead Man Walking". Cult Times. http://www.maestravida.com/weinwalk/CultT797.html. Retrieved on 2007-01-17.

- ^ Nazarro, Joe. "The Dream Given Form". TV Zone Special (#30).

[edit] References

- Aldiss, Brian, and David Hargrove. Trillion Year Spree. Atheneum, 1986.

- Amis, Kingsley. New Maps of Hell. Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1960.

- Asimov, Isaac. Asimov on Science Fiction.Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1981.

- Cadigan, Pat. The Ultimate Cyberpunk iBooks, 2002.

- de Camp, L. Sprague and Catherine Crook de Camp. Science Fiction Handbook, Revised. Owlswick Press, 1975.

- Ellison, Harlan. Dangerous Visions. Signet Books, 1967.

- Landon, Brooks. Science Fiction after 1900. Twayne Publishers, 1997.

- The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction. Ed. Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- A Companion to Science Fiction. Ed. David Seed. Blackwell, 2005.

- The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Ed. John Clute and Peter Nicholls. Second ed. Orbit, 1993.

- The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: Themes, Works, and Wonders. Ed. Gary Westfahl. Greenwood Press, 2005.

[edit] External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||