Holodomor

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Holodomor topics |

|---|

| Historical Background |

| Famines in Russia and USSR · Soviet famine of 1932-1933 |

| Soviet Government |

|

Institutions: All-Union Communist Party (Bolshevik) · Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine · Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic · Government of the Soviet Union · Secret Police |

|

Policies: |

| Investigation and Comprehension |

| 1984 International Commission · 1985 USA Commission · Causes of the Holodomor · Denial · Genocide question · Holodomor in modern politics |

The Holodomor (Ukrainian: Голодомор translation: death by starvation) refers to the famine of 1932–1933 in the Ukrainian SSR during which millions of people were starved to death because of the Soviet policies that forced farmers into collective farms.[1][2] The Holodomor is considered one of the greatest national calamities to affect the Ukrainian nation in modern history. Millions of inhabitants of Ukraine died of starvation in an unprecedented peacetime catastrophe.[1][3][4][5] Estimates on the total number of casualties within Soviet Ukraine range mostly from 2.2 million[6][7] to 10 million.[8]

The root cause of the Holodomor is a subject of scholarly debate.[9] Some scholars have argued that the Soviet policies that caused the famine may have been designed as an attack on the rise of Ukrainian nationalism, and therefore fall under the legal definition of genocide.[10][11][12][13][14] Therefore the Holodomor is also known as the "terror-famine in Ukraine"[15][16] and "famine-genocide in Ukraine".[17] Others, however, conclude that the Holodomor was a consequence of the economic problems associated with radical economic changes implemented during the period of Soviet industrialization.[5][11][12][18][19]

As of March 2008, the parliament of Ukraine and nineteen[20] governments of other countries have recognized the actions of the Soviet government as an act of genocide. The joint declaration at the United Nations in 2003 has defined the famine as the result of cruel actions and policies of the totalitarian regime that caused the deaths of millions of Ukrainians, Russians, Kazakhs and other nationalities in the USSR. On 23 October 2008 the European Parliament adopted a resolution[21] that recognized the Holodomor as a crime against humanity.[22]

Contents |

[edit] Etymology

The origins of the word Holodomor come from the Ukrainian words holod, ‘hunger’, and mor, ‘plague’,[23] possibly from the expression moryty holodom, ‘to inflict death by hunger’. The Ukrainian verb "moryty" (морити) means "to poison somebody, drive to exhaustion or to torment somebody". The perfect form of the verb "moryty" is "zamoryty" — "kill or drive to death by hunger, exhausting work". The neologism “Holodomor” is given in the modern, two-volume dictionary of the Ukrainian language as "artificial hunger, organised in vast scale by the criminal regime against the country's population."[24] Sometimes the expression is translated into English as "murder by hunger."[5]

[edit] Scope and duration

The famine affected the Ukrainian SSR as well as the Moldavian ASSR(a part of the Ukrainian S.S.R. at the time) between 1932 and 1933. However, not every part suffered from the Holodomor for the whole period; the greatest number of victims was recorded in the spring of 1933.

The first reports of mass malnutrition and deaths from starvation emerged from 2 urban area of Uman - by the time Vinnytsya and Kiev oblasts dated by beginning of January 1933. By mid-January 1933 there were reports about mass “difficulties” with food in urban areas that had been undersupplied through the rationing system and deaths from starvation among people who were withdrawn from rationing supply according to Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine Decree December 1932. By the beginning of February 1933, according to received reports from local authorities and Ukrainian GPU, the most affected area was listed as Dnipropetrovsk Oblast which also suffered from epidemics of typhus and malaria. Odessa and Kiev oblasts were second and third respectively. By mid-March most reports originated from Kiev Oblast.

By mid-April 1933 the Kharkiv Oblast reached the top of the most affected list, while Kiev, Dnipropetrovsk, Odessa, Vinnytsya, Donetsk oblasts and Moldavian SSR followed it. Last reports about mass deaths from starvation dated mid-May through the beginning of June 1933 originated from raions in Kiev and Kharkiv oblasts. The “less affected” list noted the Chernihiv Oblast and northern parts of Kiev and Vinnytsya oblasts. According to the Central Committee of the CP(b) of Ukraine Decree as of February 8 1933, no hunger cases should have remained untreated, and all local authorities were directly obliged to submit reports about numbers suffering from hunger, the reasons for hunger, number of deaths from hunger, food aid provided from local sources and centrally provided food aid required. Parallel reporting and food assistance were managed by the GPU of the Ukrainian SSR. Many regional reports and most of the central summary reports are available from present-day central and regional Ukrainian archives .[25] , There is documentary evidence of widespread cannibalism during the Holodomor.[26] The Soviet regime of the time even printed posters declaring: "To eat your own children is a barbarian act."[27]

[edit] Causes

The reasons for the famine are a subject of scholarly and political debate. Some scholars view the famine as a consequence of the economic problems associated with radical economic changes implemented during the period of Soviet industrialization.[5][11][12][18][19] However it has been suggested by other historians that the famine was an attack on Ukrainian nationalism engineered by Soviet leadership of the time and thus may fall under the legal definition of genocide.[10][11][12][13][14]

[edit] Death toll

By the end of 1933, millions of people had starved to death or had otherwise died unnaturally in Ukraine, as well as in other Soviet republics. The total estimate of the famine victims Soviet-wide is given as 6-7 million[18] or 6-8 million.[1] The Soviet Union long denied that the famine had ever taken place, and the NKVD (and later KGB) archives on the Holodomor period opened very slowly. The exact number of the victims remains unknown and is probably impossible to estimate even within a margin of error of a hundred thousand.[28]Numbers as high as seven to ten million are sometimes given in the media[29][30][31] and a number as high as ten[32] or even twenty million is sometimes cited in political speeches.[33]

One reason for estimate variance is that some assess the number of people who died within the 1933 borders of Ukraine; while others are based on deaths within current borders of Ukraine. Other estimates are based on deaths of Ukrainians in the Soviet Union. Some estimates use a very simple methodology based percentage of deaths that was reported in one area and applying the percentage to the entire country. Others use more sophisticated techniques that involves analyzing the demographic statistics based on various archival data. Some question the accuracy of Soviet censuses since the may have been doctored to support Soviet propaganda. Other estimates come from recorded discussion between world leaders like Churchill and Stalin. For example the estimate of ten million deaths, which is attributed to Soviet official sources, could be based on a misinterpretation[citation needed] of the memoirs of Winston Churchill who gave an account of his conversation with Stalin that took place on August 16, 1942.[34] In that conversation,[35] Stalin gave Churchill his estimates of the number of "kulaks" who were repressed for resisting collectivization as 10 million, in all of the Soviet Union, rather than only in Ukraine. When using this number, Stalin implied that it included not only those who lost their lives, but also forcibly deported.[34]

A number of difficulties exist when attempting to estimate casualty rates. Some estimates include the death toll from political repression including those who died in the Gulag, while others refer only to those who starved to death. In addition, many of the estimates are based on different time periods. Thus, a definitive number of deaths continues to be a source of great debate.

The results based on scientific methods obtained prior to the opening of former Soviet archives also varied widely but the range was narrower: for example, 2.5 million (Volodymyr Kubiyovych),[34] 4.8 million (Vasyl Hryshko)[34] and 5 million (Robert Conquest).[36]

One modern calculation that uses demographic data including that available from recently opened Soviet archives narrows the losses to about 3.2 million or, allowing for the lack of precise data, 3 million to 3.5 million.[3] [37] [34][38][39]

The Soviet archives show that excess deaths in Ukraine in 1932-1933 numbered 1.54 million.[40] In 1932-1933, there were a combined 1.2 million cases of typhus and 500,000 cases of typhoid fever. All major types of disease, apart from cancer, tend to increase during famine as a result of undernourishment lowering resistance and gnerating unsanitary conditions; thus these deaths resulted primarily from lowered resistance rather than starvation per se.[41] In the years 1932–34, the largest rate of increase was recorded for typhus, which is spread by lice. In conditions of harvest failure and increased poverty, the number of lice is likely to increase, and the herding of refugees at railway stations, on trains and elsewhere facilitates their spread. In 1933, the number of recorded cases was twenty times the 1929 level. The number of cases per head of population recorded in Ukraine in 1933 was already considerably higher than in the USSR as a whole. But by June 1933, incidence in Ukraine had increased to nearly ten times the January level and was higher than in the rest of the USSR taken as a whole.[42]

However, it is important to note that the number of the recorded excess deaths extracted from the birth/death statistics from the Soviet archives is self-contradictory and cannot be fully relied upon because the data fails to add up to the differences between the results of the 1927 Census and the 1937 Census.[34]

| Year | Typhus | Typhoid Fever | Relapsing Fever | Smallpox | Malaria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1913 | 120 | 424 | 30 | 67 | 3600 |

| 1918-22 | 1300 | 293 | 639 | 106 | 2940(average) |

| 1929 | 40 | 170 | 6 | 8 | 3000 |

| 1930 | 60 | 190 | 5 | 10 | 2700 |

| 1931 | 80 | 260 | 4 | 30 | 3200 |

| 1932 | 220 | 300 | 12 | 80 | 4500 |

| 1933 | 800 | 210 | 12 | 38 | 6500 |

| 1934 | 410 | 200 | 10 | 16 | 9477 |

| 1935 | 120 | 140 | 6 | 4 | 9924 |

| 1936 | 100 | 120 | 3 | 0.5 | 6500 |

Stanislav Kulchytsky summarized the natural population change.[34] The declassified Soviet statistics show a decrease of 538,000 people in the population of Soviet Ukraine between 1926 census (28,925,976) and 1937 census (28,388,000). The number of births and deaths (in thousands) according to the declassified records are given in the table (right).

According to the correction for officially non-accounted child mortality in 1933[43] by 150,000 calculated by Sergei Maksudov, the number of births for 1933 should be increased from 471,000 to 621,000. Assuming the natural mortality rates in 1933 to be equal to the average annual mortality rate in 1927-1930 (524,000 per year) a natural population growth for 1933 would have been 97,000, which is five times less than this number in the past years (1927-1930). From the corrected birth rate and the estimated natural death rate for 1933 as well as from the official data for other years the natural population growth from 1927 to 1936 gives 4.043 million while the census data showed a decrease of 538,000. The sum of the two numbers gives an estimated total demographic loss of 4.581 million people. A major hurdle in estimating the human losses due to famine is the needed to take into account the numbers involved in migration (including forced resettlement). According to the Soviet statistics, the migration balance for the population in Ukraine for 1927 - 1936 period was a loss of 1.343 million people. Even at the time when the data was taken, the Soviet statistical institutions acknowledged that its precision was worse than the data for the natural population change. Still, with the correction for this number, the total number of death in Ukraine due to unnatural causes for the given ten years was 3.238 million, and taking into account the lack of precision, especially of the migration estimate, the human toll is estimated between 3 million and 3.5 million.

| Year | Births | Deaths | Natural change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1927 | 1184 | 523 | 661 |

| 1928 | 1139 | 496 | 643 |

| 1929 | 1081 | 539 | 542 |

| 1930 | 1023 | 536 | 487 |

| 1931 | 975 | 515 | 460 |

| 1932 | 782 | 668 | 114 |

| 1933 | 471 | 1850 | -1379 |

| 1934 | 571 | 483 | 88 |

| 1935 | 759 | 342 | 417 |

| 1936 | 895 | 361 | 534 |

In addition to the direct losses from unnatural deaths, the indirect losses due to the decrease of the birth rate should be taken into account in consideration in estimating of the demographic consequences of the Famine for Ukraine. For instance, the natural population growth in 1927 was 662,000, while in 1933 it was 97,000, in 1934 it was 88,000. The combination of direct and indirect losses from Holodomor gives 4.469 million, of which 3.238 million (or more realistically 3 to 3.5 million) is the number of the direct deaths according to this estimate.

A 2002 study by Vallin et al[6] [4] [7] utilizing some similar primary sources to Kulchytsky, and performing an analysis with more sophisticated demographic tools with forward projection of expected growth from the 1926 census and backward projection from the 1939 census estimate the amount of direct deaths for 1933 as 2.582 million. This number of deaths does not reflect the total demographic loss for Ukraine from these events as the fall of the birth rate during crisis and the out-migration contribute to the latter as well. The total population shortfall from the expected value between 1926 and 1939 estimated by Vallin amounted to 4.566 million. Of this number, 1.057 million is attributed to birth deficit, 930,000 to forced out-migration, and 2.582 million to excess mortality and voluntary out-migration. With the latter assumed to be negligible this estimate gives the number of deaths as the result of the 1933 famine about 2.2 million. According to this study the life expectancy for those born in 1933 sharply fell to 10.8 years for females and to 7.3 years for males and remained abnormally low for 1934 but, as commonly expected for the post-crisis peaked in 1935–36.[4]

According to estimates[43] about 81.3% of the famine victims in Ukrainian SRR were ethnic Ukrainians, 4.5% Russians, 1.4% Jews and 1.1% were Poles. Many Belarusians, Hungarians, Volga Germans and rest nationalities became victims as well. The Ukrainian rural population was the hardest hit by the Holodomor. Since the peasantry constituted a demographic backbone of the Ukrainian nation,[44] the tragedy deeply affected the Ukrainians for many years.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, the overall number of Ukrainians who died from 1932-1933 famine is estimated as about four to five million out of six to eight million people who died in the Soviet Union as a whole.[1]

[edit] Was the Holodomor a genocide?

Robert Conquest claimed that the famine of 1932–33 was a deliberate act of mass murder, if not genocide committed as part of Joseph Stalin's collectivization program in the Soviet Union. In 2006, the Security Service of Ukraine declassified more than 5 thousand pages of Holodomor archives.[45] These documents suggest that the Soviet Regime singled out Ukraine, while regions outside it were allowed to receive humanitarian aid.[46] Some scholars says that Conquest's book on the famine is replete with errors and inconsistencies and that it deserves to be considered an expression of the Cold War. [47]

R.W. Davies and Stephen G. Wheatcroft have interacted with Conquest and note that he no longer considers the famine "deliberate".[48] Conquest -- and, by extension, Davies and Wheatcroft -- believe that, had industrialization been abandoned, the famine would have been "prevented" (Conquest), or at least significantly alleviated.

- ...we regard the policy of rapid industrialization as an underlying cause of the agricultural troubles of the early 1930s, and we do not believe that the Chinese or NEP versions of industrialization were viable in Soviet national and international circumstances.[49]

They see the leadership under Stalin as making significant errors in planning for the industrialization of agriculture.

Davies and Wheatcroft also cite an unpublished letter by Robert Conquest:

- Our view of Stalin and the famine is close to that of Robert Conquest, who would earlier have been considered the champion of the argument that Stalin had intentionally caused the famine and had acted in a genocidal manner. In 2003, Dr Conquest wrote to us explaining that he does not hold the view that "Stalin purposely incited the 1933 famine. No. What I argue is that with resulting famine imminent, he could have prevented it, but put ‘Soviet interest’ other than feeding the starving first—thus consciously abetting it".[50]

This retraction by Conquest is also noted by Kulchytsky.[14]

Some historians maintain that the famine was an unintentional consequence of collectivization, and that the associated resistance to it by the Ukrainian peasantry exacerbated an already-poor harvest.[51][52] Some researchers state that while the term Ukrainian Genocide is often used in application to the event, technically, the use of the term "genocide" is inapplicable.[13]

The statistical distribution of famine's victims among the ethnicities closely reflects the ethnic distribution of the rural population of Ukraine[53] Moldavian, Polish, German and Bulgarian population that mostly resided in the rural communities of Ukraine suffered in the same proportion as the rural Ukrainian population.[53] While ethnic Russians in Ukraine lived mostly in urban areas and the cities were affected little by the famine, the rural Russian population was affected the same way as the rural population of any other ethnicity.[53]

University of West Virginia professor Dr Mark Tauger claims that any analysis that asserts that the harvests of 1931 and 1932 were not extraordianrily low and that the famine was a political measure intentionally imposed through excessive procurements is based on an insufficient source base and an uncritical approach to the official sources. [51] However, the historian James Mace wrote that Mark Tauger's view of the famine "is not taken seriously by either Russians or Ukrainians who have studied the topic."[54]

Professor Michael Ellman of the University of Amsterdam concludes that, according to a relaxed definition of the term, the famine of 1932-33 may constitute genocide. He bases this on the actions (two of commission and one of omission: exporting grain - 1.8 million tonnes - during the mass starvation, preventing migration from famine afflicted areas and making no effort to secure grain assistance from abroad) and the attitude (that many of those starving to death were "counterrevolutionaries," "idlers" or "thieves" who fully deserved their fate) of the Stalinist regime in 1932-33. He asks:

“Throughout his career as a Soviet leader, from Tsaritsyn (1918) to the ‘Doctors' plot’ (1953), he used violence (arrests, shootings, deportations) to achieve his political goals. Is it really plausible to suppose that with these perceptions, convictions, words, actions, plans, and record, Stalin would have abstained from an efficient, cost-saving method (i.e. starvation) of repressing ‘counterrevolutionaries’ (or ‘anti-Soviet elements’) and liquidating ‘idlers’?”[55]

[edit] Denial of the Holodomor

Denial of the Holodomor is the assertion that the 1932-1933 Holodomor in Soviet Ukraine did not occur.[56][57][58][59] This denial and suppression was made in official Soviet propaganda and was supported by some Western journalists and intellectuals. [57][58][60][61][62]

Denial of the famine by Soviet authorities, including President Mikhail Kalinin and Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov, was immediate and continued into the 1980s. The Soviet party line was echoed at the time of the famine by some prominent Western journalists, including Walter Duranty and Louis Fischer. The denial of the famine was a highly successful and well orchestrated disinformation campaign by the Soviet government [56][57][58]. Stalin "had achieved the impossible: he had silenced all the talk of hunger... Millions were dying, but the nation hymned the praises of collectivization", said historian and writer Edvard Radzinsky[58]. That was the first major instance of Soviet authorities adopting Hitler's Big Lie propaganda technique to sway world opinion, to be followed by similar campaigns over the Moscow Trials and denial of the Gulag labor camp system, according to Robert Conquest [36]

[edit] Holodomor in modern politics

The famine remains a politically-charged topic; hence, heated debates are likely to continue for a long time. Until around 1990, the debates were largely between the so called "denial camp" who refused to recognize the very existence of the famine or stated that it was caused by natural reasons (such as a poor harvest), scholars who accepted reports of famine but saw it as a policy blunder[65] followed by the botched relief effort, and scholars who alleged that it was intentional and specifically anti-Ukrainian or even an act of genocide against the Ukrainians as a nation.

Nowadays, scholars agree that the famine affected millions. While it is also accepted that the famine affected other nationalities in addition to Ukrainians, the debate is still ongoing as to whether or not the Holodomor qualifies as an act of genocide, since the facts that the famine itself took place and that it was unnatural are not disputed. As far as the possible effect of the natural causes, the debate is restricted to whether the poor harvest[52] or post-traumatic stress played any role at all and to what degree the Soviet actions were caused by the country's economic and military needs as viewed by the Soviet leadership.

In 2007, President Viktor Yushchenko declared he wants "a new law criminalising Holodomor denial," while Communist Party head Petro Symonenko said he "does not believe there was any deliberate starvation at all," and accused Yushchenko of "using the famine to stir up hatred."[30] Few in Ukraine share Symonenko's interpretation of history and the number of Ukrainians who deny the famine or view it as caused by natural reasons is steadily falling.[66]

On November 10, 2003 at the United Nations twenty-five countries including Russia, Ukraine and United States signed a joint statement on the seventieth anniversary of the Holodomor with the following preamble:

In the former Soviet Union millions of men, women and children fell victims to the cruel actions and policies of the totalitarian regime. The Great Famine of 1932-1933 in Ukraine (Holodomor), which took from 7 million to 10 million innocent lives and became a national tragedy for the Ukrainian people. In this regard we note activities in observance of the seventieth anniversary of this Famine, in particular organized by the Government of Ukraine.

Honouring the seventieth anniversary of the Ukrainian tragedy, we also commemorate the memory of millions of Russians, Kazakhs and representatives of other nationalities who died of starvation in the Volga River region, Northern Caucasus, Kazakhstan and in other parts of the former Soviet Union, as a result of civil war and forced collectivization, leaving deep scars in the consciousness of future generations.[67]

One of the biggest arguments is that the famine was preceded by the onslaught on the Ukrainian national culture, a common historical detail preceding many centralized actions directed against the nations as a whole. Nation-wide, the political repression of 1937 (The Great Purge) under the guidance of Nikolay Yezhov were known for their ferocity and ruthlessness, but Lev Kopelev wrote, "In Ukraine 1937 began in 1933", referring to the comparatively early beginning of the Soviet crackdown in Ukraine.[68]

While the famine was well documented at the time, its reality has been disputed for ideological reasons, for instance by the Soviet government and its spokespeople (as well as apologists for the Soviet regime), by others due to being deliberately misled by the Soviet government (such as George Bernard Shaw), and, in at least one case, Walter Duranty, for personal gain.

An example of a late-era Holodomor objector is Canadian and journalist Douglas Tottle, author of Fraud, Famine and Fascism: The Ukrainian Genocide Myth from Hitler to Harvard (published by Moscow-based Soviet publisher Progress Publishers in 1987). Tottle claims that while there were severe economic hardships in Ukraine, the idea of the Holodomor was fabricated as propaganda by Nazi Germany and William Randolph Hearst to justify a German invasion.

[edit] Remembrance

To honour those who perished in the Holodomor, monuments have been dedicated and public events held annually in Ukraine and worldwide. The first public monument to the Holodomor was erected and dedicated outside City Hall in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada in 1983 to mark the 50th anniversary of the famine-genocide. Since then, the fourth Saturday in November has in many jurisdictions been marked as the official day of remembrance for people who died as a result of the 1932-33 Holodomor and political repression.[69]

In 2006, the Holodomor Remembrance Day took place on November 25. President Viktor Yushchenko directed, in decree No. 868/2006, that a minute of silence should be observed at 4 o'clock in the afternoon on that Saturday. The document specified that flags in Ukraine should fly at half-staff as a sign of mourning. In addition, the decree directed that entertainment events are to be restricted and television and radio programming adjusted accordingly.[70]

In 2007, the 74th anniversary of the Holodomor was commemorated in Kiev for three days on the Maidan Nezalezhnosti. As part of the three day event, from November 23-25th, video testimonies of the communist regime's crimes in Ukraine, and documentaries by famous domestic and foreign film directors are being shown. Additionally, experts and scholars gave lectures on the topic.[71] Additionally, on November 23, 2007, the National Bank of Ukraine issued a set of two commemorative coins remembering the Holodomor.[72]

On November 17, 2007 members from Aleksandr Dugin's radical Russian nationalist group the Eurasian Youth Union broke into the Ukrainian cultural center in Moscow and smashed an exhibition on the famine.[73]

On November 22, 2008, Ukrainian Canadians marked the beginning of National Holodomor Awareness Week. Citizenship, Immigration and Multiculturalism Minister Jason Kenney attended a vigil in Kiev.[74]

On December 2, 2008, the groundbreaking ceremony was held in Washington, D.C. for the Holodomor Memorial.[75]

|

A Holodomor memorial at the Andrushivka village cemetery, Vinnytsia Oblast, Ukraine. |

|||

|

A Holodomor memorial in Poltava Oblast, Ukraine |

A memorial cross in Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine |

||

|

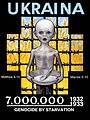

Poster by artist Leonid Denysenko from Australia |

| This article's citation style may be unclear. The references used may be clearer with a different or consistent style of citation, footnoting, or external linking. |

[edit] Notes and References

- ^ a b c d - The famine of 1932–33 - Encyclopædia Britannica: "The Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932–33—a man-made demographic catastrophe unprecedented in peacetime. Of the estimated six to eight million people who died in the Soviet Union, about four to five million were Ukrainians... Its deliberate nature is underscored by the fact that no physical basis for famine existed in Ukraine... Soviet authorities set requisition quotas for Ukraine at an impossibly high level. Brigades of special agents were dispatched to Ukraine to assist in procurement, and homes were routinely searched and foodstuffs confiscated... The rural population was left with insufficient food to feed itself."

- ^ Engerman, David (203). Modernization from the Other Shore. Harvard University Press. p. 194. ISBN 0674011511. http://books.google.com/books?id=UkFlO7hoxOMC&pg=PA194&dq.

- ^ a b Stalislav Kulchytsky, "Demographic losses in Ukrainian in the twentieth century", Zerkalo Nedeli, October 2-8, 2004. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- ^ a b c Jacques Vallin, France Mesle, Serguei Adamets, Serhii Pyrozhkov, A New Estimate of Ukrainian Population Losses during the Crises of the 1930s and 1940s, Population Studies, Vol. 56, No. 3. (Nov., 2002), pp. 249-264

- ^ a b c d Helen Fawkes , Legacy of famine divides Ukraine, BBC News, 24 November 2006

- ^ a b France Meslé, Gilles Pison, Jacques Vallin France-Ukraine: Demographic Twins Separated by History, Population and societies, N°413, juin 2005

- ^ a b ce Meslé, Jacques Vallin Mortalité et causes de décès en Ukraine au XXè siècle + CDRom ISBN 2-7332-0152-2 CD online data (partially - http://www.ined.fr/fichier/t_publication/cdrom_mortukraine/cdrom.htm

- ^ Shelton, Dinah (2005). Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity. Detroit ; Munich: Macmillan Reference, Thomson Gale. pp. 1059. ISBN 0028658507.

- ^ "The scholary debate, however is overshadowed by the inconceivable suffering, which all scholars admit occured.": Moss, Walter (2005). A History of Russia. Anthem Press. p. 250. ISBN 1843310341. http://books.google.com/books?id=yMwdWFtgV0QC&pg=RA1-PA250&dq.

- ^ a b Peter Finn, Aftermath of a Soviet Famine, The Washington Post, April 27, 2008, "There are no exact figures on how many died. Modern historians place the number between 2.5 million and 3.5 million. Yushchenko and others have said at least 10 million were killed."

- ^ a b c d Dr. David Marples, The great famine debate goes on..., ExpressNews (University of Alberta), originally published in Edmonton Journal, November 30, 2005

- ^ a b c d Stanislav Kulchytsky, "Holodomor of 1932–1933 as genocide: the gaps in the proof", Den, February 17, 2007, in Russian, in Ukrainian

- ^ a b c Yaroslav Bilinsky (1999). "Was the Ukrainian Famine of 1932–1933 Genocide?". Journal of Genocide Research 1 (2): 147–156. doi:. http://www.faminegenocide.com/resources/bilinsky.html.

- ^ a b c Stanislav Kulchytsky, "Holodomor-33: Why and how?", Zerkalo Nedeli, November 25—December 1, 2006, in Russian, in Ukrainian.

- ^ Davies, Norman (2006). Europe East and West. London: Jonathan Cape. p. 145. ISBN 0224069241. http://books.google.com/books?id=z7VmAAAAMAAJ&q=%22Terror-Famine+in+Ukraine%22&dq=%22Terror-Famine+in+Ukraine%22&ei=qlCSSa22FpDUlQSX_pTJCg&pgis=1.

- ^ Baumeister, Roy (1999). Evil: Inside Human Violence and Cruelty. Macmillan. p. 179. ISBN 0805071652. http://books.google.com/books?id=tGxA-lduhHkC&pg=PA179&dq.

- ^ Sternberg, Robert (2008). The Nature of Hate. Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 0521896983. http://books.google.com/books?id=TFT2l-RH9FIC&pg=RA1-PA67&dq=%22Famine-Genocide+in+Ukraine%22&lr=&ei=PVOSSfrYAomulQSq_sjNCg&client=firefox-a.

- ^ a b c С. Уиткрофт (Stephen G. Wheatcroft), "О демографических свидетельствах трагедии советской деревни в 1931—1933 гг." (On demographic evidence of the tragedy of the Soviet village in 1931-1833), "Трагедия советской деревни: Коллективизация и раскулачивание 1927-1939 гг.: Документы и материалы. Том 3. Конец 1930-1933 гг.", Российская политическая энциклопедия, 2001, ISBN 5-8243-0225-1, с. 885, Приложение № 2

- ^ a b 'Stalinism' was a collective responsibility - Kremlin papers, The News in Brief, University of Melbourne, 19 June 1998, Vol 7 No 22

- ^ sources differ on interpreting various statements from different branches of different governments as to whether they amount to the official recognition of the Famine as Genocide by the country. For example, after the statement issued by the Latvian Sejm on March 13, 2008, the total number of countries is given as 19 (according to Ukrainian BBC: "Латвія визнала Голодомор ґеноцидом"), 16 (according to Korrespondent, Russian edition: "После продолжительных дебатов Сейм Латвии признал Голодомор геноцидом украинцев"), "more than 10" (according to Korrespondent, Ukrainian edition: "Латвія визнала Голодомор 1932-33 рр. геноцидом українців")

- ^ European Parliament resolution on the commemoration of the Holodomor, the Ukraine artificial famine (1932-1933)

- ^ European Parliament recognises Ukrainian famine of 1930s as crime against humanity (Press Release 23-10-2008)

- ^ Ukrainian holod (голод, ‘hunger’, compare Russian golod) should not be confused with kholod (холод, ‘cold’). For details, see romanization of Ukrainian. Mor means ‘plague’ in the sense of a disastrous evil or affliction, or a sudden unwelcome outbreak. See wiktionary:plague.

- ^ Голодомор, in "Velykyi tlumachnyi slovnyk suchasnoi ukrainsʹkoi movy: 170 000 sliv", chief ed. V. T. Busel, Irpin, Perun (2004), ISBN 9665690132

- ^ Голод 1932-1933 років на Україні: очима істориків, мовою документів. [1]

- ^ An article by historian Vasily Sokur, containing citations from documents. The author suggests that never in the history of mankind has cannibalism been so widespread as it was during the Holodomor. - http://www.facts.kiev.ua/archive/2008-11-21/92027/. Accessed 21 November 2008.

- ^ Steven Bela Vardy and Agnes Huszar Vardy. Cannibalism in Stalin's Russia and Mao's China. Duquesne University, East European Quartarly, XLI, No.2, 2007

- ^ Valeriy Soldatenko, "A starved 1933: subjective thoughts on objective processes", Zerkalo Nedeli, June 28, 2003 – July 4, 2003. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian

- ^ BBC report

- ^ a b Laura Sheeter, "Ukraine remembers famine horror", BBC News, November 24, 2007

- ^ The Ukrainian politician Stepan Khmara during the hearings in the Verkhovna Rada (quoted through Kulchytsky): "I would like to address the scientists, particularly, Stanislav Kulchytsky, who attempts to mark down the number of victims and counts them as 3–3.5 million. I studied these questions analyzing the demographic statistics as early as in 1970s and concluded that the number of victims was no less than 7 million"

Cited through Stanislav Kulchytsky, "Reasons of the 1933 famine in Ukraine. Through the pages of one almost forgotten book" Zerkalo Nedeli, August 16-22, 2003. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian. However, Stanislav Kulchytsky in Демографічні наслідки голодомору 1933 р. в Україні. (Demographic consequence of Holodomor of 1933 in Ukraine), Kiev, Institute of History, 2003, p. 4, notes that the demographic data were opened only in late 1980s; Stepan Khmara had no access to such data in 1970s. - ^ Viktor Yushchenko, "Holodomor", The Wall Street Journal, 27.11.2007

- ^ Ukrainian President Yushchenko: Yushchenko's Address before Joint Session of U.S. Congress

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stanislav Kulchytsky, "How many of us perished in Holodomor in 1933", Zerkalo Nedeli, November 23-29, 2002. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian

- ^ Valentin Berezhkov, "Kak ya stal perevodchikom Stalina", Moscow, DEM, 1993, ISBN 5-85207-044-0. p. 317

- ^ a b Robert Conquest, The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine Oxford University Press New York (1986) ISBN 0-195-04054-6

- ^ Stanislav Kulchytsky, Hennadiy Yefimenko. Демографічні наслідки голодомору 1933 р. в Україні. Всесоюзний перепис 1937 р. в Україні: документи та матеріали (Demographic consequence of Holodomor of 1933 in Ukraine. The all-Union census of 1937 in Ukraine), Kiev, Institute of History, 2003. pp. 42-63

- ^ Stalislav Kulchytsky, "Reasons of the 1933 famine in Ukraine. Through the pages of one almost forgotten book" Zerkalo Nedeli, August 16-22, 2003. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- ^ Stanislav Kulchytsky, "Reasons of the 1933 famine in Ukraine-2", Zerkalo Nedeli, October 4-10, 2003. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian

- ^ Davies and Wheatcroft, p.415

- ^ Davies and Wheatcroft, p. 429

- ^ Davies and Wheatcroft, p. 512

- ^ a b Sergei Maksudov, "Losses Suffered by the Population of the USSR 1918–1958", in The Samizdat Register II, ed R. Medvedev (London–New York 1981)

- ^ Robert Potocki, "Polityka państwa polskiego wobec zagadnienia ukraińskiego w latach 1930-1939" (in Polish, English summary), Lublin 2003, ISBN 83-917615-4-1

- ^ Служба безпеки України

- ^ SBU documents show that Moscow singled out Ukraine in famine 5tv - Ukraine Channel Five. 22 November 2006. Retrieved 23 November 2006

- ^ Mark Tauger. Published correspondence (pdf)

- ^ "Debate: Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932-33: A Reply to Ellman", in Europe-Asia Studies, vol. 58, No. 4, June 2006, pp.625-633. (note on conquest (p. 629))

- ^ "Debate: Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932-33: A Reply to Ellman", in Europe-Asia Studies, vol. 58, No. 4, June 2006, pp.625-633. (p. 626))

- ^ Davies, R.W. & Wheatcroft, S.G. (2004) The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931 – 1933 (Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan), p 441, n. 145.

- ^ a b Mark B. Tauger, The 1932 Harvest and the Famine of 1933, Slavic Review, Volume 50, Issue 1 (Spring, 1991), 70-89, (PDF)

- ^ a b See also the acrimonious exchange between Tauger and Conquest.

- ^ a b c Stanislav Kulchytsky, Hennadiy Yefimenko. Демографічні наслідки голодомору 1933 р. в Україні. Всесоюзний перепис 1937 р. в Україні: документи та матеріали (Demographic consequence of Holodomor of 1933 in Ukraine. The all-Union census of 1937 in Ukraine), Kiev, Institute of History, 2003. pp.63-72

- ^ James Mace, Intellectual Europe on Ukrainian Genocide, The Day, October 21, 2003

- ^ Michael Ellman, Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932-33 Revisited Europe-Asia Studies, Routledge. Vol. 59, No. 4, June 2007, 663-693. PDF file

- ^ Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; no text was provided for refs named Black

- ^ a b c Richard Pipes Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime, Vintage books, Random House Inc., New York, 1995, ISBN 0-394-50242-6, pages 232-236.

- ^ a b c d Edvard Radzinsky Stalin: The First In-depth Biography Based on Explosive New Documents from Russia's Secret Archives, Anchor, (1997) ISBN 0-385-47954-9, pages 256-259

- ^ Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; no text was provided for refs named reflections

- ^ Famine denial The Ukrainian Weekly, July 14, 2002, No. 28, Vol. LXX

- ^ The Soviet Union dismissed all references to the famine as anti-Soviet propaganda. Denial of the famine declined after the Communist Party lost power and the Soviet empire disintegrated @ Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity By Dinah Shelton; Page 1055 ISBN 0028658485

- ^ After over half a century of denial, in January 1990 theCommunist Party of Ukraine adopted a special resolution admitting that the Ukrainian Famine had indeed occurred, cost millions of lives... Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts - Page 93 ISBN 0415944295

- ^ Dmytro Horbachov, Fullest Expression of Pure feeling, Welcome to Ukraine, 1998, No 1.

- ^ Andrew Wilson, "The Ukrainians: Unexpected Nation", Yale University Press, 2002, ISBN 0300093098, p.144

- ^ J. Arch Getty, "The Future Did Not Work", The Atlantic Monthly, Boston: March 2000, Vol. 285, Iss.3, pg.113

- ^ Большинство украинцев считают Голодомор актом геноцида, Korrespondent.net, November 20, 2007

- ^ Joint Statement on the Great Famine of 1932-1933 in Ukraine (Holodomor) on Monday, November 10, 2003 at the United Nations in New York

- ^ Subtelny, Orest (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press,. ISBN 0-80205-808-6.

- ^ Bradley, Lara. "Ukraine's 'Forced Famine' Officially Recognized. The Sundbury Star. 3 January 1999. URL Accessed 12 October 2006

- ^ Yushchenko, Viktor. Decree No. 868/2006 by President of Ukraine. Regarding the Remembrance Day in 2006 for people who died as a result of Holodomor and political repressions (Ukrainian)

- ^ "Ceremonial events to commemorate Holodomor victims to be held in Kiev for three days." National Radio Company of Ukraine. URL Accessed 25 November 2007

- ^ Commemorative Coins "Holodomor – Genocide of the Ukrainian People". National Bank of Ukraine.URL Accessed 25 June 2008

- ^ Ukraine Demanding That Russia Punish Eurasian Youth Union Members For Smashing Famine Exhibition In Moscow

- ^ "Ukrainian-Canadians mark famine's 75 anniversasry". CTV.ca. http://www.ctv.ca/servlet/ArticleNews/story/CTVNews/20081122/ukrainian_famine_081122/20081122?hub=TopStories. Retrieved on 2008-11-23.

- ^ "Ukrainian Genocide Memorial Groundbreaking Ceremony in Washington, D.C.". Renaissance Research. http://renaissanceresearch.blogspot.com/2008/12/ukrainian-genocide-memorial.html. Retrieved on 2008-12-02.

[edit] Further reading

[edit] Declarations and legal acts

- Findings of the Commission on the Ukraine Famine, U.S. Commission on the Ukraine Famine, Report to Congress. Adopted by the Commission, April 19, 1988

- Joint declaration at the United Nations in connection with 70th anniversary of the Great Famine in Ukraine 1932-1933

- Address of the Verkhovna Rada to the Ukrainian nation on commemorating the victims of Holodomor 1932-1933 (in Ukrainian)

[edit] Books and articles

- Ammende, Ewald, Human life in Russia, (Cleveland: J.T. Zubal, 1984), Reprint, Originally published: London, England: Allen & Unwin, 1936.

- The Black Deeds of the Kremlin: a white book, S.O. Pidhainy, Editor-In-Chief, (Toronto: Ukrainian Association of Victims of Russian-Communist Terror, 1953), (Vol. 1 Book of testimonies. Vol. 2. The Great Famine in Ukraine in 1932–1933).

- Conquest, Robert, The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine, (Edmonton: The University of Alberta Press in Association with the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 1986).

- Davies, R.W., The Socialist offensive: the collectivization of Soviet agriculture, 1929–1930, (London: Macmillan, 1980).

- Der ukrainische Hunger-Holocaust: Stalins verschwiegener Volkermond 1932/33 an 7 Millionen ukrainischen Bauern im Spiegel geheimgehaltener Akten des deutschen Auswartigen Amtes, (Sonnebuhl: H. Wild, 1988), By Dmytro Zlepko. [eine Dokumentation, herausgegeben und eingeleitet von Dmytro Zlepko].

- Dolot, Miron, Execution by Hunger: The Hidden Holocaust, a survivor's account of the Famine of 1932–1933 in Ukraine, (New York City: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1985).

- Dolot, Miron, Who killed them and why?: in remembrance of those killed in the Famine of 1932–1933 in Ukraine, (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University, Ukrainian Studies Fund, 1984).

- Dushnyk, Walter, 50 years ago: the famine holocaust in Ukraine, (New York: Toronto: World Congress of Free Ukrainians, 1983).

- Famine in the Soviet Ukraine 1932–1933: a memorial exhibition, Widener Library, Harvard University, prepared by Oksana Procyk, Leonid Heretz, James E. Mace (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard College Library, distributed by Harvard University Press, 1986).

- Famine in Ukraine 1932-33, edited by Roman Serbyn and Bohdan Krawchenko (Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 1986). [Selected papers from a conference held at the Universite du Quebec a Montreal in 1983).

- The Great Famine in Ukraine: the unknown holocaust: in solemn observance of the Ukrainian famine of 1932–1933, (Compiled and edited by the editors of the Ukrainian Weekly [Roma Hadzewycz, George B. Zarycky, Martha Kolomayets] Jersey City, N.J.: Ukrainian National Association, 1983).

- Ellman, Michael (09 2005). "The Role of Leadership Perceptions and of Intent in the Soviet Famine of 1931–1934" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies (Routledge) 57 (6): 823–41. doi:. http://www.paulbogdanor.com/left/soviet/famine/ellman.pdf.

- Gregorovich, Andrew, “Black Famine in Ukraine 1932-33: A Struggle for Existence”, Forum: A Ukrainian Review, No. 24, (Scranton: Ukrainian Workingmen's Association, 1974).

- Halii, Mykola, Organized famine in Ukraine, 1932–1933, (Chicago: Ukrainian Research and Information Institute, 1963).

- Holod na Ukraini, 1932–1933: vybrani statti, uporiadkuvala Nadiia Karatnyts'ka, (New York: Suchasnist', 1985).

- Hlushanytsia, Pavlo, "Tretia svitova viina Pavla Hlushanytsi == The third world war of Pavlo Hlushanytsia, translated by Vera Moroz, (Toronto: Anabasis Magazine, 1986). [Bilingual edition in Ukrainian and English].

- Holod 1932-33 rokiv na Ukraini: ochyma istorykiv, movoij dokumentiv, (Kyiv: Vydavnytstvo politychnoyi literatury Ukrainy, 1990).

- Hryshko, Vasyl, Ukrains'kyi 'Holokast', 1933, (New York: DOBRUS; Toronto: SUZHERO, 1978).

- Hryshko, Vasyl, The Ukrainian Holocaust of 1933, Edited and translated by Marco Carynnyk, (Toronto: Bahrianyi Foundation, SUZHERO, DOBRUS, 1983).

- International Commission of Inquiry into the 1932-33 Famine in Ukraine, Proceedings [transcript], May 23-27, 1988, Brussels, Belgium, [Jakob W.F. Sundberg, President; Legal Counsel, World Congress of Free Ukrainians: John Sopinka, Alexandra Chyczij; Legal Council for the Commission, Ian A. Hunter, 1988.

- International Commission of Inquiry into the 1932-33 Famine in Ukraine. Proceedings [transcript], October 21 – November 5, 1988, New York City, [Jakob W.F. Sundberg, President; Counsel for the Petitioner, William Liber; General Counsel, Ian A. Hunter], 1988.

- International Commission of Inquiry into the 1932–1933 Famine in Ukraine. Final report, [Jacob W.F. Sundberg, President], 1990. [Proceedings of the International Commission of Inquiry and its Final report are in typescript, contained in 6 vols. Copies available from the World Congress of Free Ukrainians, Toronto].

- Kalynyk, Oleksa, Communism, the enemy of mankind: documents about the methods and practise of Russian Bolshevik occupation in Ukraine, (London, England: The Ukrainian Youth Association in Great Britain, 1955).

- Klady, Leonard, “Famine Film Harvest of Despair”, Forum: A Ukrainian Review, No. 61, Spring 1985, (Scranton: Ukrainian Fraternal Association, 1985).

- Kolektyvizatsia і Holod na Ukraini 1929–1933: Zbirnyk documentiv і materialiv, Z.M. Mychailycenko, E.P. Shatalina, S.V. Kulcycky, eds., (Kyiv: Naukova Dumka, 1992).

- Kostiuk, Hryhory, Stalinist rule in Ukraine: a study of the decade of mass terror, 1929–1939, (Munich: Institut zur Erforschung der UdSSSR, 1960).

- Kovalenko, L.B. & Maniak, B.A., eds., Holod 33: Narodna knyha-memorial, (Kyiv: Radians'kyj pys'mennyk, 1991).

- Krawchenko, Bohdan, Social change and national consciousness in twentieth-century Ukraine, (Basingstoke: Macmillan in association with St. Anthony's College, Oxford, 1985).

- Luciuk, Lubomyr (and L Grekul), Holodomor: Reflections on the Great Famine of 1932-1933 in Soviet Ukraine (Kashtan Press, Kingston, 2008).

- Lettere da Kharkov: la carestia in Ucraina e nel Caucaso del Nord nei rapporti dei diplomatici italiani, 1932-33, a cura di Andrea Graziosi, (Torino: Einaudi, 1991).

- Mace, James E., Communism and the dilemma of national liberation: national communism in Soviet Ukraine, 1918–1933, (Cambridge, Mass.: Distributed by Harvard University Press for the Ukrainian Research Institute and the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S., 1983).

- Makohon, P., Svidok: Spohady pro 33-ho, (Toronto: Anabasis Magazine, 1983).

- Martchenko, Borys, La famine-genocide en Ukraine: 1932–1933, (Paris: Publications de l'Est europeen, 1983).

- Marunchak, Mykhailo H., Natsiia v borot'bi za svoie isnuvannia: 1932 і 1933 v Ukraini і diiaspori, (Winnipeg: Nakl. Ukrains'koi vil'noi akademii nauk v Kanadi, 1985).

- Memorial, compiled by Lubomyr Y. Luciuk and Alexandra Chyczij; translated into English by Marco Carynnyk, (Toronto: Published by Kashtan Press for Canadian Friends of “Memorial”, 1989). [Bilingual edition in Ukrainian and English. this is a selection of resolutions, aims and objectives, and other documents, pertaining to the activities of the Memorial Society in Ukraine].

- Mishchenko, Oleksandr, Bezkrovna viina: knyha svidchen', (Kyiv: Molod', 1991).

- Oleksiw, Stephen, The agony of a nation: the great man-made famine in Ukraine, 1932–1933, (London: The National Committee to Commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Artificial Famine in Ukraine, 1932–1933, 1983).

- Pavel P. Postyshev, envoy of Moscow in Ukraine 1933–1934, [selected newspaper articles, documents, and sections in books], (Toronto: World Congress of Free Ukrainians, Secretariat, [1988], The 1932-33 Famine in Ukraine research documentation).

- Pidnayny, Alexandra, A bibliography of the great famine in Ukraine, 1932–1933, (Toronto: New Review Books, 1975).

- Pravoberezhnyi, Fedir, 8,000,000: 1933-i rik na Ukraini, (Winnipeg: Kultura і osvita, 1951).

- Senyshyn, Halyna, Bibliohrafia holody v Ukraini 1932–1933, (Ottawa: Montreal: UMMAN, 1983).

- Solovei, Dmytro, The Golgotha of Ukraine: eye-witness accounts of the famine in Ukraine, compiled by Dmytro Soloviy, (New York: Ukrainian Congress Committee of America, 1953).

- Stradnyk, Petro, Pravda pro soviets'ku vladu v Ukraini, (New York: N. Chyhyryns'kyi, 1972).

- Taylor, S.J., Stalin's apologist: Walter Duranty, the New York Time's man in Moscow, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

- The Foreign Office and the famine: British documents on Ukraine and the great famine of 1932–1933, edited by Marco Carynnyk, Lubomyr Y. Luciuk and Bohdan Kor.

- The man-made famine in Ukraine (Washington D.C.: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1984). [Seminar. Participants: Robert Conquest, Dana Dalrymple, James Mace, Michael Nowak].

- United States, Commission on the Ukraine Famine. Investigation of the Ukrainian Famine, 1932–1933: report to Congress / Commission on the Ukraine Famine, [Daniel E. Mica, Chairman; James E. Mace, Staff Director]. (Washington D.C.: U.S. G.P.O.: For sale by the Supt. of Docs, U.S. G.P.O., 1988), (Dhipping list: 88-521-P).

- United States, Commission on the Ukrainian Famine. Oral history project of the Commission on the Ukraine Famine, James E. Mace and Leonid Heretz, eds. (Washington, D.C.: Supt. of Docs, U.S. G.P.O., 1990).

- Velykyi holod v Ukraini, 1932-33: zbirnyk svidchen', spohadiv, dopovidiv ta stattiv, vyholoshenykh ta drukovanykh v 1983 rotsi na vidznachennia 50-littia holodu v Ukraini—The Great Famine in Ukraine 1932–1933: a collection of memoirs, speeches amd essays prepared in 1983 in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Famine in Ukraine during 1932-33, [Publication Committee members: V. Rudenko, T. Khokhitva, P. Makohon, F. Podopryhora], (Toronto: Ukrains'ke Pravoslavne Bratstvo Sv. Volodymyra, 1988), [Bilingual edition in Ukrainian and English].

- Verbyts'kyi, M., Naibil'shyi zlochyn Kremlia: zaplianovanyi shtuchnyi holod v Ukraini 1932–1933 rokiv, (London, England: DOBRUS, 1952).

- Voropai, Oleksa, V deviatim kruzi, (London, England: Sum, 1953).

- Voropai, Oleksa, The Ninth Circle: In Commemoration of the Victims of the Famine of 1933, Olexa Woropay; edited with an introduction by James E. Mace, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University, Ukrainian Studies Fund, 1983).

- Marco Carynnyk, Lubomyr Luciuk and Bohdan S Kordan, eds, The Foreign Office and the Famine: British Documents on Ukraine and the Great Famine of 1932-1933, foreword by Michael Marrus (Kingston: Limestone Press, 1988)

- Robert Conquest (1987), The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195051807

- Robert W. Davies; Wheatcroft, Stephen G., The Years of Hunger. Soviet Agriculture 1931-1933, Houndmills 2004 ISBN 3-412-10105-2, also ISBN 0-333-31107-8

- Robert W. Davies; Wheatcroft, Stephen G., “Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932-33 - A Reply to Ellman”, in Europe-Asia Studies Vol. 58 (2006), 4, pp. 625–633.

- Miron Dolot, Execution by Hunger: The Hidden Holocaust, New York: W.W Norton & Company, 1985, xvi + 231 pp. ISBN 0-393-01886-5.

- Barbara Falk, Sowjetische Städte in der Hungersnot 1932/33. Staatliche Ernährungspolitik und städtisches Alltagsleben (= Beiträge zur Geschichte Osteuropas 38), Köln: Böhlau Verlag 2005 ISBN 3-412-10105-2

- Wasyl Hryshko, The Ukrainian Holocaust of 1933, (Toronto: 1983, Bahriany Foundation)

- Stanislav Kulchytsky, Hennadiy Yefimenko. Демографічні наслідки голодомору 1933 р. в Україні. Всесоюзний перепис 1937 р. в Україні: документи та матеріали (Demographic consequence of Holodomor of 1933 in Ukraine. The all-Union census of 1937 in Ukraine), Kiev, Institute of History, 2003.

- R. Kusnierz, Ukraina w latach kolektywizacji i Wielkiego Glodu (1929-1933),Torun, 2005

- Leonard Leshuk, ed., Days of Famine, Nights of Terror: Firsthand Accounts of Soviet Collectivization, 1928-1934 (Kingston: Kashtan Press, 1995)

- Lubomyr Luciuk, ed., Not Worthy: Walter Duranty's Pulitzer Prize and The New York Times (Kingston: Kashtan Press, 2004)

- Czesław Rajca (2005). Głód na Ukrainie. Lublin/Toronto: Werset. ISBN 83-60133-04-2.

- Stephen G. Wheatcroft. “Towards Explaining the Soviet Famine of 1931-1933: Political and Natural Factors in Perspective”, in Food and Foodways Vol. 12 (2004), No. 2-3, pp. 104–136.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Holodomor |

- "Gareth Jones' international exposure of the Holodomor, plus many related background articles". http://www.garethjones.org/soviet_articles/. Retrieved on 2006-07-05.

- (Ukrainian) Famine in Ukraine 1932–1933 at the Central State Archive of Ukraine (photos, links)

- Yaroslav Bilinsky, Was the Ukrainian Famine of 1932-1933 Genocide?, Journal of Genocide Research , 1(2), pages= 147–156 (June 1999), available at external site

- Stanislav Kulchytsky, Italian Research on the Holodomor, October 2005.

- (English) Stanislav Kulchytsky, "Why did Stalin exterminate the Ukrainians? Comprehending the Holodomor. The position of Soviet historians" - Six part series from Den: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6; Kulchytsky on Holodomor 1-6

- (Russian)/(Ukrainian) Valeriy Soldatenko, "A starved 1933: subjective thoughts on objective processes", Zerkalo Nedeli, June 28 - July 4 2003. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- (Russian)/(Ukrainian) Stanislav Kulchytsky's articles in Zerkalo Nedeli, Kiev, Ukraine"

- "How many of us perish in Holodomor on 1933", November 23, 2002 – November 29, 2002. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- "Reasons of the 1933 famine in Ukraine. Through the pages of one almost forgotten book" August 16-22, 2003. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- "Reasons of the 1933 famine in Ukraine-2", October 4, 2003 – October 10, 2003. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- "Demographic losses in Ukraine in the twentieth century", October 2, 2004 – October 8, 2004. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- "Holodomor-33: Why and how?" November 25 - December 1. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- UKRAINIAN FAMINE Revelations from the Russian Archives at the Library of Congress

- Photos of Holodomor by Sergei Melnikoff

- The General Committee decided this afternoon not to recommend the inclusion of an item on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932-1933 in Ukraine.

- Case Study: The Great Ukrainian Famine of 1932-33 By Nicolas Werth / CNRS - France

- Holomodor - Famine in Soviet Ukraine 1932-1933

- Famine in the Soviet Union 1929-1934 - collection of archive materials