List of trigonometric identities

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In mathematics, trigonometric identities are equalities that involve trigonometric functions that are true for every single value of the occurring variables.[citation needed] These identities are useful whenever expressions involving trigonometric functions need to be simplified. An important application is the integration of non-trigonometric functions: a common technique involves first using the substitution rule with a trigonometric function, and then simplifying the resulting integral with a trigonometric identity.

[edit] Notation

To avoid the confusion caused by the ambiguity of sin−1(x), the reciprocals and inverses of trigonometric functions are often displayed as in this table. In representing the cosecant function, the longer form 'cosec' is sometimes used in place of 'csc'.

| Function | Inverse function | Reciprocal | Inverse reciprocal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sine | sin | arcsine | arcsin | cosecant | csc | arccosecant | arccsc |

| cosine | cos | arccosine | arccos | secant | sec | arcsecant | arcsec |

| tangent | tan | arctangent | arctan | cotangent | cot | arccotangent | arccot |

Different angular measures can be appropriate in different situations. This table shows some of the more common systems. Radians is the default angular measure and is the one you use if you use the exponential definitions. All angular measures are unitless.

| Degrees | 30 | 45 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 180 | 270 | 360 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radians | π / 6 | π / 4 | π / 3 | π / 2 | 2π / 3 | π | 3π / 2 | 2π |

| Grads | 33 ⅓ | 50 | 66 ⅔ | 100 | 133 ⅓ | 200 | 300 | 400 |

[edit] Basic relationships

| Pythagorean trigonometric identity |  [1][2] [1][2] |

|---|---|

| Ratio identity |  [3][2] [3][2] |

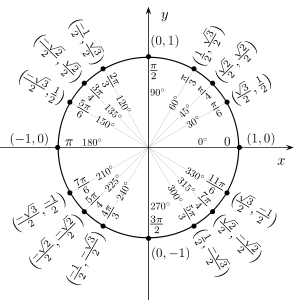

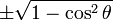

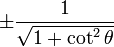

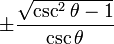

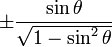

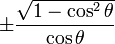

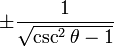

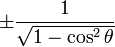

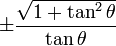

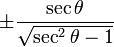

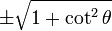

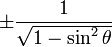

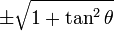

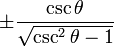

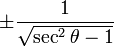

From the two identities above, the following table can be extrapolated. Note however that these conversion equations may not provide the correct sign (+ or −). For example, if sin θ = 1/2, the conversion in the table indicates that  , though it is possible that

, though it is possible that  . More information would be needed about which quadrant θ lies in to determine a single, exact answer. This only applies to the transformations with the square root function.

. More information would be needed about which quadrant θ lies in to determine a single, exact answer. This only applies to the transformations with the square root function.

| Function | (sinθ) | (cosθ) | (tanθ) | (cscθ) | (secθ) | (cotθ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sinθ = |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| cosθ = |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| tanθ = |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| cscθ = |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| secθ = |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| cotθ = |  |

|

|

|

|

|

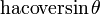

[edit] Historic shorthands

The versine, coversine, haversine, and exsecant were used in navigation. For example the haversine formula was used to calculate the distance between two points on a sphere. They are rarely used today.

| Name(s) | Abbreviation(s) | Value [5] |

|---|---|---|

| versed sine, versine |   |

|

| versed cosine, vercosine, coversed sine, coversine |

|

|

| haversed sine, haversine |   |

|

| haversed cosine, havercosine, hacoversed sine, hacoversine, cohaversed sine, cohaversine |

|

|

| exterior secant, exsecant |  |

|

| exterior cosecant, excosecant |  |

|

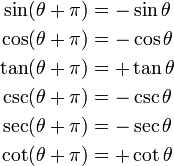

[edit] Symmetry, shifts, and periodicity

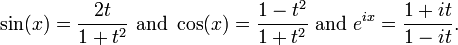

By examining the unit circle, the following properties of the trigonometric functions can be established.

[edit] Symmetry

When the trigonometric functions are reflected from certain angles, the result is often one of the other trigonometric functions. This leads to the following identities:

| Reflected in θ = 0[6] | Reflected in θ = π / 2 (co-function identities)[7] |

Reflected in θ = π |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

[edit] Shifts and periodicity

By shifting the function round by certain angles, it is often possible to find different trigonometric functions that express the result more simply. Some examples of this are shown by shifting functions round by π/2, π and 2π radians. Because the periods of these functions are either π or 2π, there are cases where the new function is exactly the same as the old function without the shift.

| Shift by π/2 | Shift by π Period for tan and cot[8] |

Shift by 2π Period for sin, cos, csc and sec[9] |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

[edit] Angle sum and difference identities

These are also known as the addition and subtraction theorems or formulæ. The quickest way to prove these is Euler's formula.

| Sine |  [10][11] [10][11] |

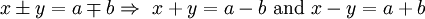

Note: From plus-minus sign.

|

|---|---|---|

| Cosine |  [12][11] [12][11] |

|

| Tangent |  [13][11] [13][11] |

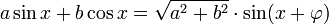

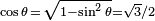

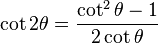

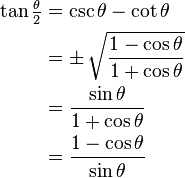

[edit] Matrix form

The sum and difference formulæ for sine and cosine can be written in matrix form, thus:

[edit] Sines and cosines of sums of infinitely many terms

In these two identities an asymmetry appears that is not seen in the case of sums of finitely many terms: in each product, there are only finitely many sine factors and cofinitely many cosine factors.

If only finitely many of the terms θi are nonzero, then only finitely many of the terms on the right side will be nonzero because sine factors will vanish, and in each term, all but finitely many of the cosine factors will be unity.

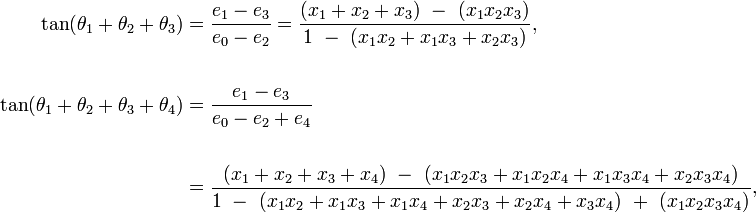

[edit] Tangents of sums of finitely many terms

Let ek be the kth-degree elementary symmetric polynomial in the variables xi = tan(θi ), for i = 1, ..., n, k = 0, ..., n. Then

the number of terms depending on n.

For example:

and so on. The general case can be proved by mathematical induction.

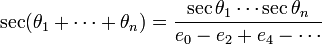

[edit] Secants of sums of finitely many terms

where ek is the kth-degree elementary symmetric polynomial in the n variables xi = tan θi, i = 1, ..., n, and the number of terms in the denominator depends on n.

For example,

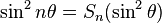

[edit] Multiple-angle formulae

| Tn is the nth Chebyshev polynomial |  [14] [14] |

|---|---|

| Sn is the nth spread polynomial |  |

| de Moivre's formula, i is the Imaginary unit |  [15] [15] |

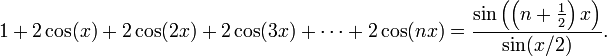

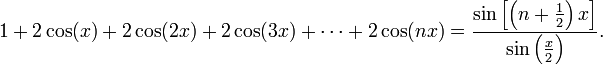

(This function of x is the Dirichlet kernel.)

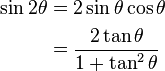

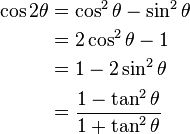

[edit] Double-, triple-, and half-angle formulae

These can be shown by using either the sum and difference identities or the multiple-angle formulae.

| Double-angle formulae[16][17] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

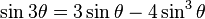

| Triple-angle formulae[18][14] | |||

|

|

|

|

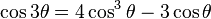

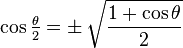

| Half-angle formulae[19][20] | |||

|

|

|

|

- See also Tangent half-angle formula.

A formula for computing the trigonometric identities for the third-angle exists, but it requires finding the zeroes of the cubic equation  , where x is the value of the sine function at some angle and d is the known value of the sine function at the triple angle. However, the discriminant of this equation is negative, so this equation has three real roots (of which only one is the solution within the correct third-circle) but none of these solutions is reducible to a real algebraic expression, as they use intermediate complex numbers under the cubic roots, (which may be expressed in terms of real-only functions only if using hyperbolic functions). As a consequence, it is not possible to express the trigonometric values of angles that are not multiples of 3 degrees divided by any power of two, if using a real-only algebric expression (for example sin(1°)).

, where x is the value of the sine function at some angle and d is the known value of the sine function at the triple angle. However, the discriminant of this equation is negative, so this equation has three real roots (of which only one is the solution within the correct third-circle) but none of these solutions is reducible to a real algebraic expression, as they use intermediate complex numbers under the cubic roots, (which may be expressed in terms of real-only functions only if using hyperbolic functions). As a consequence, it is not possible to express the trigonometric values of angles that are not multiples of 3 degrees divided by any power of two, if using a real-only algebric expression (for example sin(1°)).

- See also Casus irreducibilis.

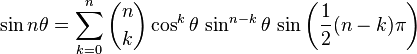

[edit] Sine, cosine, and tangent of multiple angles

tan nθ can be written in terms of tan θ using the recurrence relation:

cot nθ can be written in terms of cot θ using the recurrence relation:

[edit] Tangent of an average

Setting either α or β to 0 gives the usual tangent half-angle formulæ.

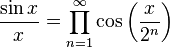

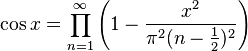

[edit] Euler's infinite product

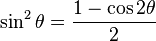

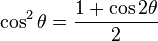

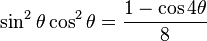

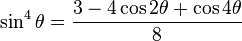

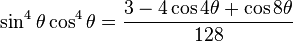

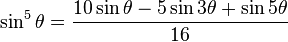

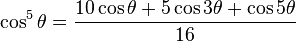

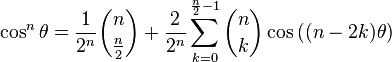

[edit] Power-reduction formulas

Obtained by solving the second and third versions of the cosine double-angle formula.

| Sine | Cosine | Other |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

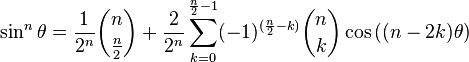

and in general terms of powers of sin θ or cos θ the following is true, and can be deduced using De Moivre's formula, Euler's formula and binomial expansion.

| Cosine | Sine | |

|---|---|---|

| if n is odd |  |

|

| if n is even |  |

|

[edit] Product-to-sum and sum-to-product identities

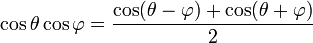

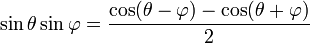

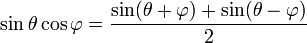

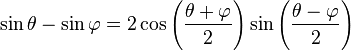

The product-to-sum identities can be proven by expanding their right-hand sides using the angle addition theorems. See beat frequency for an application of the sum-to-product formulæ.

|

|

[edit] Other related identities

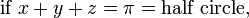

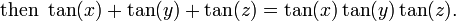

If x, y, and z are the three angles of any triangle, or in other words

(If any of x, y, z is a right angle, one should take both sides to be ∞. This is neither +∞ nor −∞; for present purposes it makes sense to add just one point at infinity to the real line, that is approached by tan(θ) as tan(θ) either increases through positive values or decreases through negative values. This is a one-point compactification of the real line.)

[edit] Ptolemy's theorem

(The first three equalities are trivial; the fourth is the substance of this identity.) Essentially this is Ptolemy's theorem adapted to the language of trigonometry.

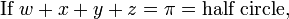

[edit] Linear combinations

For some purposes it is important to know that any linear combination of sine waves of the same period but different phase shifts is also a sine wave with the same period, but a different phase shift. In the case of a linear combination of a sine and cosine wave (which is just a sine wave with a phase shift of π/2), we have

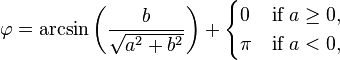

where

or equivalently

More generally, for an arbitrary phase shift, we have

where

and

[edit] Other sums of trigonometric functions

Sum of sines and cosines with arguments in arithmetic progression:

For any a and b:

where atan2(y, x) is the generalization of arctan(y/x) which covers the entire circular range.

The above identity is sometimes convenient to know when thinking about the Gudermannian function, which relates the circular and hyperbolic trigonometric functions without resorting to complex numbers.

If x, y, and z are the three angles of any triangle, i.e. if x + y + z = π, then

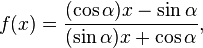

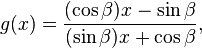

[edit] Certain linear fractional transformations

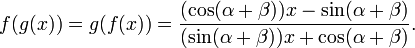

If ƒ(x) is given by the linear fractional transformation

and similarly

then

More tersely stated, if for all α we let ƒα be what we called ƒ above, then

If x is the slope of a line, then ƒ(x) is the slope of its rotation through an angle of −α.

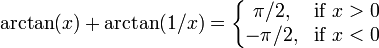

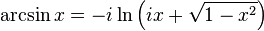

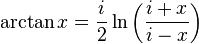

[edit] Inverse trigonometric functions

[edit] Compositions of trig and inverse trig functions

![\sin[\arccos(x)]=\sqrt{1-x^2} \,](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/a/b/2/ab24dbd6c097d578b9ba6d5ef8af13da.png) |

![\tan[\arcsin (x)]=\frac{x}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/4/0/0/4005da685c90f33d145f122e34baaf66.png) |

![\sin[\arctan(x)]=\frac{x}{\sqrt{1+x^2}}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/e/7/b/e7b8c103e90d3201a10be0ddfe90a2cb.png) |

![\tan[\arccos (x)]=\frac{\sqrt{1 - x^2}}{x}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/7/c/4/7c4a9d034cd65dae312f3d4593636d40.png) |

![\cos[\arctan(x)]=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+x^2}}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/6/5/b/65b8e718cbd943d44c5c0086c0cad02f.png) |

![\cot[\arcsin (x)]=\frac{\sqrt{1 - x^2}}{x}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/8/8/4/88435402b69aee3ce7c1e5f1ac715a4d.png) |

![\cos[\arcsin(x)]=\sqrt{1-x^2} \,](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/a/2/9/a29cf2e566f9cc26ed2bb5b73337799e.png) |

![\cot[\arccos (x)]=\frac{x}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/8/e/e/8ee9f8bedda57dd3f7c86e7e2f5049fe.png) |

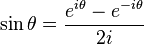

[edit] Relation to the complex exponential function

and hence the corollary:

where i2 = − 1.

[edit] Infinite product formula

For applications to special functions, the following infinite product formulae for trigonometric functions are useful:[26][27]

|

|

|

[edit] Identities without variables

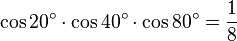

The curious identity

is a special case of an identity that contains one variable:

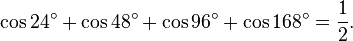

A similar-looking identity is

and in addition

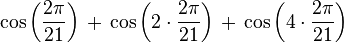

The following is perhaps not as readily generalized to an identity containing variables (but see explanation below):

Degree measure ceases to be more felicitous than radian measure when we consider this identity with 21 in the denominators:

The factors 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 10 may start to make the pattern clear: they are those integers less than 21/2 that are relatively prime to (or have no prime factors in common with) 21. The last several examples are corollaries of a basic fact about the irreducible cyclotomic polynomials: the cosines are the real parts of the zeroes of those polynomials; the sum of the zeroes is the Möbius function evaluated at (in the very last case above) 21; only half of the zeroes are present above. The two identities preceding this last one arise in the same fashion with 21 replaced by 10 and 15, respectively.

[edit] Computing π

An efficient way to compute π is based on the following identity without variables, due to Machin:

or, alternatively, by using an identity of Euler:

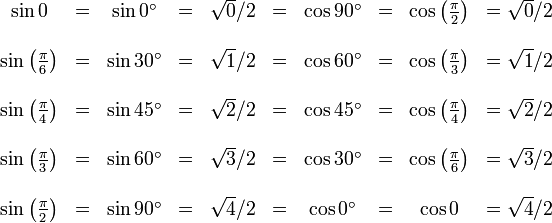

[edit] A useful mnemonic for certain values of sines and cosines

For certain simple angles, the sines and cosines take the form  for 0 ≤ n ≤ 4, which makes them easy to remember.

for 0 ≤ n ≤ 4, which makes them easy to remember.

[edit] Other interesting values

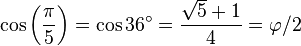

With the golden ratio φ:

Also see exact trigonometric constants.

[edit] Calculus

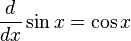

In calculus the relations stated below require angles to be measured in radians; the relations would become more complicated if angles were measured in another unit such as degrees. If the trigonometric functions are defined in terms of geometry, their derivatives can be found by verifying two limits. The first is:

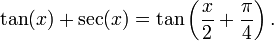

verified using the unit circle and squeeze theorem. It may be tempting to propose to use L'Hôpital's rule to establish this limit. However, if one uses this limit in order to prove that the derivative of the sine is the cosine, and then uses the fact that the derivative of the sine is the cosine in applying L'Hôpital's rule, one is reasoning circularly—a logical fallacy. The second limit is:

verified using the identity tan(x/2) = (1 − cos x)/sin x. Having established these two limits, one can use the limit definition of the derivative and the addition theorems to show that (sin x)′ = cos x and (cos x)′ = −sin x. If the sine and cosine functions are defined by their Taylor series, then the derivatives can be found by differentiating the power series term-by-term.

The rest of the trigonometric functions can be differentiated using the above identities and the rules of differentiation:[28][29][30]

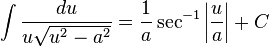

The integral identities can be found in "list of integrals of trigonometric functions". Some generic forms are listed below.

[edit] Implications

The fact that the differentiation of trigonometric functions (sine and cosine) results in linear combinations of the same two functions is of fundamental importance to many fields of mathematics, including differential equations and Fourier transforms.

[edit] Exponential definitions

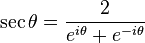

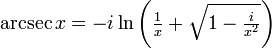

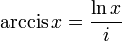

| Function | Inverse function[31] |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[edit] Miscellaneous

[edit] Dirichlet kernel

The Dirichlet kernel Dn(x) is the function occurring on both sides of the next identity:

The convolution of any integrable function of period 2π with the Dirichlet kernel coincides with the function's nth-degree Fourier approximation. The same holds for any measure or generalized function.

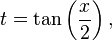

[edit] Extension of half-angle formulae

If we set

then[32]

where eix is the same as cis(x).

This substitution of t for tan(x/2), with the consequent replacement of sin(x) by 2t/(1 + t2) and cos(x) by (1 − t2)/(1 + t2) is useful in calculus for converting rational functions in sin(x) and cos(x) to functions of t in order to find their antiderivatives. For more information see tangent half-angle formula.

[edit] See also

- Trigonometry

- Proofs of trigonometric identities

- Uses of trigonometry

- Tangent half-angle formula

- Law of cosines

- Law of sines

- Law of tangents

- Mollweide's formula

- Pythagorean theorem

- Exact trigonometric constants (values of sine and cosine expressed in surds)

- Derivatives of trigonometric functions

- Hyperbolic function

- Prosthaphaeresis

- Versine and haversine

- Exsecant

[edit] Notes

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.10

- ^ a b Eric W. Weisstein, Trigonometry at MathWorld.

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.3

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 73, 4.3.45

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 78, 4.3.147

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.13–15

- ^ The Elementary Identities

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.9

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.7–8

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.16

- ^ a b c Eric W. Weisstein, Trigonometric Addition Formulas at MathWorld.

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.17

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.18

- ^ a b Eric W. Weisstein, Multiple-Angle Formulas at MathWorld.

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 74, 4.3.48

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.24–26

- ^ Eric W. Weisstein, Double-Angle Formulas at MathWorld.

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.27–28

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.20–22

- ^ Eric W. Weisstein, Half-Angle Formulas at MathWorld.

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.31–33

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.34–39

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 74, 4.3.47

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 71, 4.3.2

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 71, 4.3.1

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 75, 4.3.89–90

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 85, 4.5.68–69

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 77, 4.3.105–110

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 82, 4.4.52–57

- ^ Finney, Ross (2003). Calculus : Graphical, Numerical, Algebraic. Glenview, Illinois: Prentice Hall. pp. 159–161. ISBN 0-13-063131-0.

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 80, 4.4.26–31

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 72, 4.3.23

[edit] References

- Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene A., eds. (1972), Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables, New York: Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-61272-0

[edit] External links

- Values of Sin and Cos, expressed in surds, for integer multiples of 3° and of 5⅝°, and for the same angles Csc and Sec and Tan.

![\left[\begin{matrix} \cos\alpha & -\sin\alpha \\ \sin\alpha & \cos\alpha \end{matrix}\right] \left[\begin{matrix}\cos\beta & -\sin\beta \\ \sin\beta & \cos\beta\end{matrix}\right] = \left[\begin{matrix}\cos(\alpha+\beta) & -\sin(\alpha+\beta) \\ \sin(\alpha+\beta) & \cos(\alpha+\beta) \end{matrix}\right].](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/d/e/a/deae6a0317e1ce69df09e663c288ef73.png)