Political corruption

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Political corruption is the use of governmental powers by government officials for illegitimate private gain. Misuse of government power for other purposes, such as repression of political opponents and general police brutality, is not considered political corruption. Neither are illegal acts by private persons or corporations not directly involved with the government. An illegal act by an officeholder constitutes political corruption only if the act is directly related to their official duties.

All forms of government are susceptible to political corruption. Forms of corruption vary, but include bribery, extortion, cronyism, nepotism, patronage, graft, and embezzlement. While corruption may facilitate criminal enterprise such as drug trafficking, money laundering, and trafficking, it is not restricted to these organized crime activities. In some nations, corruption is so common that it is expected when ordinary businesses or citizens interact with government officials. The end point of political corruption is a kleptocracy, literally "rule by thieves".

The activities that constitute illegal corruption differ depending on the country or jurisdiction. Certain political funding practices that are legal in one place may be illegal in another. In some countries, government officials have broad or poorly defined powers, and the line between what is legal and illegal can be difficult to draw.

Bribery around the world is estimated at about $1 trillion (£494bn), and the burden of corruption falls disproportionately on the bottom billion people living in extreme poverty.[1]

Contents |

[edit] Effects

[edit] Effects on politics, administration, and institutions

Corruption poses a serious development challenge. In the political realm, it undermines democracy and good governance by flouting or even subverting formal processes. Corruption in elections and in legislative bodies reduces accountability and distorts representation in policymaking; corruption in the judiciary compromises the rule of law; and corruption in public administration results in the unfair provision of services. More generally, corruption erodes the institutional capacity of government as procedures are disregarded, resources are siphoned off, and public offices are bought and sold. At the same time, corruption undermines the legitimacy of government and such democratic values as trust and tolerance.

[edit] Economic effects

Corruption also undermines economic development by generating considerable distortions and inefficiency. In the private sector, corruption increases the cost of business through the price of illicit payments themselves, the management cost of negotiating with officials, and the risk of breached agreements or detection. Although some claim corruption reduces costs by cutting red tape, the availability of bribes can also induce officials to contrive new rules and delays. Openly removing costly and lengthy regulations are better than covertly allowing them to be bypassed by using bribes. Where corruption inflates the cost of business, it also distorts the playing field, shielding firms with connections from competition and thereby sustaining inefficient firms.

Corruption also generates economic distortions in the public sector by diverting public investment into capital projects where bribes and kickbacks are more plentiful. Officials may increase the technical complexity of public sector projects to conceal or pave way for such dealings, thus further distorting investment. Corruption also lowers compliance with construction, environmental, or other regulations, reduces the quality of government services and infrastructure, and increases budgetary pressures on government.

Economists argue that one of the factors behind the differing economic development in Africa and Asia is that in the former, corruption has primarily taken the form of rent extraction with the resulting financial capital moved overseas rather invested at home (hence the stereotypical, but often accurate, image of African dictators having Swiss bank accounts). In Nigeria, for example, more than $400 billion was stolen from the treasury by Nigeria's leaders between 1960 and 1999.[2] University of Massachusetts researchers estimated that from 1970 to 1996, capital flight from 30 sub-Saharan countries totaled $187bn, exceeding those nations' external debts.[3] (The results, expressed in retarded or suppressed development, have been modeled in theory by economist Mancur Olson.) In the case of Africa, one of the factors for this behavior was political instability, and the fact that new governments often confiscated previous government's corruptly-obtained assets. This encouraged officials to stash their wealth abroad, out of reach of any future expropriation. In contrast, corrupt administrations in Asia like Suharto's have often taken a cut on everything (requiring bribes), but otherwise provided more of the conditions for development, through infrastructure investment, law and order, etc.

[edit] Environmental and social effects

Corruption facilitates environmental destruction. Even the corrupt countries may formally have legislation to protect the environment, it cannot be enforced if the officials can be easily bribed. The same applies to social rights such as worker protection, unionization and prevention of child labor. Violation of these laws and rights enables corrupt countries to gain an illegitimate economic advantage in the international market.

As the Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen has observed that "there is no such thing as an apolitical food problem." While drought and other naturally occurring events may trigger famine conditions, it is government action or inaction that determines its severity, and often even whether or not a famine will occur. Governments with strong tendencies towards kleptocracy can undermine food security even when harvests are good. Officials often steal state property. In Bihar, India, more than 80% of the subsidized food aid to poor is stolen by corrupt officials.[4] Similarly, food aid is often robbed at gunpoint by governments, criminals and warlords alike, and sold for a profit. The 20th century is full of many examples of governments undermining the food security of their own nations – sometimes intentionally.[5]

[edit] Types of corruption

[edit] Bribery

Bribery requires two participants: one to give the bribe, and one to take it. In some countries the culture of corruption extends to every aspect of public life, making it extremely difficult for individuals to stay in business without resorting to bribes. Bribes may be demanded in order for an official to do something he is already paid to do. They may also be demanded in order to bypass laws and regulations. In some developing nations, up to half of the population has paid bribes during the past 12 months.[6]

[edit] Graft

While bribery includes an intent to influence or be influenced by another for personal gain, which is often difficult to prove, graft only requires that the official gains something of value, not part of his official pay, when doing his work. Large "gifts" qualify as graft, and most countries have laws against it. (For example, any gift over $200 value made to the President of the United States is considered to be a gift to the Office of the Presidency and not to the President himself. The outgoing President must buy it if he or she wants to keep it.) Another example of graft is a politician using his knowledge of zoning to purchase land which he knows is planned for development, before this is publicly known, and then selling it at a significant profit. This is comparable to insider trading in business.

[edit] Patronage

Patronage refers to favoring supporters, for example with government employment. This may be legitimate, as when a newly elected government changes the top officials in the administration in order to effectively implement its policy. It can be seen as corruption if this means that incompetent persons, as a payment for supporting the regime, are selected before more able ones. In nondemocracies many government officials are often selected for loyalty rather than ability. They may be almost exclusively selected from a particular group (for example, Sunni Arabs in Saddam Hussein's Iraq, the nomenklatura in the Soviet Union, or the Junkers in Imperial Germany) that support the regime in return for such favors.

[edit] Nepotism and cronyism

Favoring relatives (nepotism) or personal friends (cronyism) is a form of illegitimate private gain. This may be combined with bribery, for example demanding that a business should employ a relative of an official controlling regulations affecting the business. The most extreme example is when the entire state is inherited, as in North Korea or Syria. A milder form of cronyism is an "old boy network", in which appointees to official positions are selected only from a closed and exclusive social network – such as the alumni of particular universities – instead of appointing the most competent candidate.

Seeking to harm enemies becomes corruption when official powers are illegitimately used as means to this end. For example, trumped-up charges are often brought up against journalists or writers who bring up politically sensitive issues, such as a politician's acceptance of bribes.

[edit] Embezzlement

Embezzlement is outright theft of entrusted funds. It is a misappropriation of property.

Another common type of embezzlement is that of entrusted government resources; for example, when a director of a public enterprise employs company workers to build or renovate his own house.

[edit] Kickbacks

A kickback is an official's share of misappropriated funds allocated from his or her organization to an organization involved in corrupt bidding. For example, suppose that a politician is in charge of choosing how to spend some public funds. He can give a contract to a company that is not the best bidder, or allocate more than they deserve. In this case, the company benefits, and in exchange for betraying the public, the official receives a kickback payment, which is a portion of the sum the company received. This sum itself may be all or a portion of the difference between the actual (inflated) payment to the company and the (lower) market-based price that would have been paid had the bidding been competitive. Kickbacks are not limited to government officials; any situation in which people are entrusted to spend funds that do not belong to them are susceptible to this kind of corruption. (See: Anti-competitive practices, Bid rigging.)

[edit] Unholy alliance

An unholy alliance is a coalition among seemingly antagonistic groups, especially if one is religious,[7] for ad hoc or hidden gain. Like patronage, unholy alliances are not necessarily illegal, but unlike patronage, by its deceptive nature and often great financial resources, an unholy alliance can be much more dangerous to the public interest. An early, well-known use of the term was by Theodore Roosevelt (TR):

- "To destroy this invisible Government, to dissolve the unholy alliance between corrupt business and corrupt politics is the first task of the statesmanship of the day." - 1912 Progressive Party Platform, attributed to TR[8] and quoted again in his autobiography[9] where he connects trusts and monopolies (sugar interests, Standard Oil, etc.) to Woodrow Wilson, Howard Taft, and consequently both major political parties.

[edit] Involvement in organized crime

An illustrative example of official involvement in organized crime can be found from 1920s and 1930s Shanghai, where Huang Jinrong was a police chief in the French concession, while simultaneously being a gang boss and co-operating with Du Yuesheng, the local gang ringleader. The relationship kept the flow of profits from the gang's gambling dens, prostitution, and protection rackets undisturbed.

The United States accused Manuel Noriega's government in Panama of being a "narcokleptocracy", a corrupt government profiting on illegal drug trade. Later the U.S. invaded Panama and captured Noriega.

[edit] Conditions favorable for corruption

| This article is in a list format that may be better presented using prose. You can help by converting this section to prose, if appropriate. Editing help is available. (March 2009) |

Some[who?] argue that the following conditions are favorable for corruption:

- Information deficits

- Lack of government transparency.

- Lacking freedom of information legislation. The Indian Right to Information Act 2005 has "already engendered mass movements in the country that is bringing the lethargic, often corrupt bureaucracy to its knees and changing power equations completely."[10]

- Contempt for or negligence of exercising freedom of speech and freedom of the press.

- Weak accounting practices, including lack of timely financial management.

- Lack of measurement of corruption. For example, using regular surveys of households and businesses in order to quantify the degree of perception of corruption in different parts of a nation or in different government institutions may increase awareness of corruption and create pressure to combat it. This will also enable an evaluation of the officials who are fighting corruption and the methods used.

- Tax havens which tax their own citizens and companies but not those from other nations and refuse to disclose information necessary for foreign taxation. This enables large scale political corruption in the foreign nations.[11]

- Lacking control over NEGATIVE the government.

- Democracy absent or dysfunctional. See illiberal democracy.

- Lacking civic society and non-governmental organizations which monitor the government.

- An individual voter may have a rational ignorance regarding politics, especially in nationwide elections, since each vote has little weight.

- Weak rule of law.

- Weak legal profession.

- Weak judicial independence.

- Lacking protection of whistleblowers.

- Lack of benchmarking, that is continual detailed evaluation of procedures and comparison to others who do similar things, in the same government or others, in particular comparison to those who do the best work. The Peruvian organization Ciudadanos al Dia has started to measure and compare transparency, costs, and efficiency in different government departments in Peru. It annually awards the best practices which has received widespread media attention. This has created competition among government agencies in order to improve.[12]

- Opportunities and incentives

- Individual officials routinely handle cash, instead of handling payments by giro or on a separate cash desk — illegitimate withdrawals from supervised bank accounts are much more difficult to conceal.

- Public funds are centralized rather than distributed. For example, if $1,000 is embezzled from local agency that has $2,000 funds, it easier to notice than from national agency with $2,000,000 funds. See the principle of subsidiarity.

- Large, unsupervised public investments.

- Sale of state-owned property and privatization.

- Poorly-paid government officials.

- Government licenses needed to conduct business, e.g., import licenses, encourage bribing and kickbacks.

- Long-time work in the same position may create relationships inside and outside the government which encourage and help conceal corruption and favoritism. Rotating government officials to different positions and geographic areas may help prevent this.

- Costly political campaigns, with expenses exceeding normal sources of political funding.

- Less interaction with officials reduces the opportunities for corruption. For example, using the Internet for sending in required information, like applications and tax forms, and then processing this with automated computer systems. This may also speed up the processing and reduce unintentional human errors. See e-Government.

- A windfall from exporting abundant natural resources may encourage corruption.[13] (See Resource curse)

- War and other forms of conflict correlate with a breakdown of public security.

- Social conditions

- Self-interested closed cliques and "old boy networks".

- Family-, and clan-centered social structure, with a tradition of nepotism/favouritism being acceptable.

- A gift economy, such as the Chinese guanxi or the Soviet blat system, emerges in a Communist centrally planned economy.

- In societies where personal integrity is rated as less important than other characteristics (by contrast, in societies such as 18th and 19th century England, 20th century Japan and post-war western Germany, where society showed almost obsessive regard for "honor" and personal integrity, corruption was less frequently seen)[citation needed]

- Lacking literacy and education among the population.

- Frequent discrimination and bullying among the population.

[edit] Relation to economic freedom

Lack of economic freedom explains 71 % of corruption.[14] Below is a list of examples of governmental activities that limit economic freedom, create opportunities for corruption (incentives for individuals and/or companies to buy privileges or favors worth of money, from politicians or officials) and have in recent economic history also lead to corruption:

- Licenses, permits etc.

- Foreign trade restrictions. Officials may then, e.g., sell import or export permits.

- Credit bailouts.

- State ownership of utilities and natural resources. 'In analyzing India's state-run irrigation system, professor Shyam Kamath - - wrote: Public-sector irrigation systems everywhere are typically plagued with cost and time overruns, endemic inefficiency, chronic excess demands, and widespread corruption and rent-seeking.'

- Access to loans at below-market rates. In Chile, '$4.6 billion was awarded to government banks in direct subsidies through "soft" loans' between 1940 and 1973.[15]

[edit] Size of public sector

It is a controversial issue whether the size of the public sector per se results in corruption. As mentioned above, low degree of economic freedom explains 71 % of corruption. The actual share may be even greater, as also past regulation affects the current level of corruption due to the slowth of cultural changes (e.g., it takes time for corrupted officials to adjust to changes in economic freedom).[16] The size of public sector in terms of taxation is only one component of economic un-freedom, so the empirical studies on economic freedom do not directly answer this question.

Extensive and diverse public spending is, in itself, inherently at risk of cronyism, kickbacks and embezzlement. Complicated regulations and arbitrary, unsupervised official conduct exacerbate the problem. This is one argument for privatization and deregulation. Opponents of privatization see the argument as ideological. The argument that corruption necessarily follows from the opportunity is weakened by the existence of countries with low to non-existent corruption but large public sectors, like the Nordic countries.[17] However, these countries score high on the Ease of Doing Business Index, due to good and often simple regulations, and have rule of law firmly established. Therefore, due to their lack of corruption in the first place, they can run large public sectors without inducing political corruption.

Like other governmental economic activities, also privatization, such as in the sale of government-owned property, is particularly at the risk of cronyism. Privatizations in Russia and Latin America were accompanied by large scale corruption during the sale of the state owned companies. Those with political connections unfairly gained large wealth, which has discredited privatization in these regions. While media have reported widely the grand corruption that accompanied the sales, studies have argued that in addition to increased operating efficiency, daily petty corruption is, or would be, larger without privatization, and that corruption is more prevalent in non-privatized sectors. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that extralegal and unofficial activities are more prevalent in countries that privatized less.[18]

There is the counter point, however, that oligarchy industries can be quite corrupt ( "competition" like collusive price-fixing, pressuring dependent businesses, etc. ), and only by having a portion of the market owned by someone other than that oligarchy, i.e. public sector, can keep them in line ( if the public sector gas company is making money & selling gas for 1/2 of the price of the private sector companies... the private sector companies won't be able to simultaneously gouge to that degree & keep their customers: the competition keeps them in line ). Private sector corruption can increase the poverty/helplessness of the population, so it can affect government corruption, in the long-term.

In the European Union, the principle of subsidiarity is applied: a government service should be provided by the lowest, most local authority that can competently provide it. An effect is that distribution of funds into multiple instances discourages embezzlement, because even small sums missing will be noticed. In contrast, in a centralized authority, even minute proportions of public funds can be large sums of money.

[edit] Governmental corruption

If the highest echelons of the governments also take advantage from corruption or embezzlement from the state's treasury, it is sometimes referred with the neologism kleptocracy. Members of the government can take advantage of the natural resources (e.g., diamonds and oil in a few prominent cases) or state-owned productive industries. A number of corrupt governments have enriched themselves via foreign aid, which is often spent on showy buildings and armaments.

A corrupt dictatorship typically results in many years of general hardship and suffering for the vast majority of citizens as civil society and the rule of law disintegrate. In addition, corrupt dictators routinely ignore economic and social problems in their quest to amass ever more wealth and power.

The classic case of a corrupt, exploitive dictator often given is the regime of Marshal Mobutu Sese Seko, who ruled the Democratic Republic of the Congo (which he renamed Zaire) from 1965 to 1997. It is said that usage of the term kleptocracy gained popularity largely in response to a need to accurately describe Mobutu's regime. Another classic case is Nigeria, especially under the rule of General Sani Abacha who was de facto president of Nigeria from 1993 until his death in 1998. He is reputed to have stolen some US$3-4 billion. He and his relatives are often mentioned in Nigerian 419 letter scams claiming to offer vast fortunes for "help" in laundering his stolen "fortunes", which in reality turn out not to exist.[19] More than $400 billion was stolen from the treasury by Nigeria's leaders between 1960 and 1999.[20]

More recently, articles in various financial periodicals, most notably Forbes magazine, have pointed to Fidel Castro, General Secretary of the Republic of Cuba since 1959, of likely being the beneficiary of up to $900 million, based on "his control" of state-owned companies.[21] Opponents of his regime claim that he has used money amassed through weapons sales, narcotics, international loans and confiscation of private property to enrich himself and his political cronies who hold his dictatorship together, and that the $900 million published by Forbes is merely a portion of his assets, although that needs to be proven.[22]

[edit] Whistleblowers

[edit] Campaign contributions

In the political arena, it is difficult to prove corruption. For this reason, there are often unproved rumors about many politicians, sometimes part of a smear campaign.

Politicians are placed in apparently compromising positions because of their need to solicit financial contributions for their campaign finance. If they then appear to be acting in the interests of those parties that funded them, this gives rise to talk of political corruption. Supporters may argue that this is coincidental. Cynics wonder why these organizations fund politicians at all, if they get nothing for their money.

Laws regulating campaign finance in the United States require that all contributions and their use should be publicly disclosed. Many companies, especially larger ones, fund both the Democratic and Republican parties. Certain countries, such as France, ban altogether the corporate funding of political parties. Because of the possible circumvention of this ban with respect to the funding of political campaigns, France also imposes maximum spending caps on campaigning; candidates that have exceeded those limits, or that have handed misleading accounting reports, risk having their candidacy ruled invalid, or even be prevented from running in future elections. In addition, the government funds political parties according to their successes in elections. In some countries, political parties are run solely off subscriptions (membership fees).

Even legal measures such as these have been argued to be legalized corruption, in that they often favor the political status quo. Minor parties and independents often argue that efforts to rein in the influence of contributions do little more than protect the major parties with guaranteed public funding while constraining the possibility of private funding by outsiders. In these instances, officials are legally taking money from the public coffers for their election campaigns to guarantee that they will continue to hold their influential and often well-paid positions.

[edit] Measuring corruption

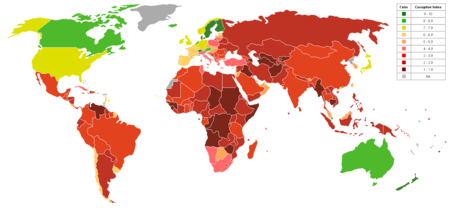

Measuring corruption statistically is difficult if not impossible due to the illicit nature of the transaction and imprecise definitions of corruption.[23] While "corruption" indices first appeared in 1995 with the Corruption Perceptions Index, all of these metrics address different proxies for corruption, such as public perceptions of the extent of the problem.[24]

Transparency International, an anti-corruption NGO, pioneered this field with the Corruption Perceptions Index, first released in 1995. This work is often credited with breaking a taboo and forcing the issue of corruption into high level development policy discourse. Transparency International currently publishes three measures, updated annually: a Corruption Perceptions Index (based on aggregating third-party polling of public perceptions of how corrupt different countries are); a Global Corruption Barometer (based on a survey of general public attitudes toward and experience of corruption); and a Bribe Payers Index, looking at the willingness of foreign firms to pay bribes. The Corruption Perceptions Index is the best known of these metrics, though it has drawn much criticism [25],[26][27] and may be declining in influence.[28]

The World Bank collects a range of data on corruption, including a set of indicators of governance and institutional quality. Moreover, one of the six dimensions of governance measured by the Worldwide Governance Indicators is Control of Corruption, which is defined as "the extent to which power is exercised for private gain, including both petty and grand forms of corruption, as well as 'capture' of the state by elites and private interests."[29] While the definition itself is fairly precise, the data aggregated into the Worldwide Governance Indicators is based on any available polling: questions range from "is corruption a serious problem?" to measures of public access to information, and not consistent across countries. Despite these weaknesses, the global coverage of these datasets has led to their widespread adoption, most notably by the Millennium Challenge Corporation.[30]

In part in response to these criticisms, a second wave of corruption metrics has been created by Global Integrity, the International Budget Partnership and many lesser known local groups, starting with the Global Integrity Index, first published in 2004. These second wave projects aim not to create awareness, but to create policy change via targeting resources more effectively and creating checklists toward incremental reform. Global Integrity and the International Budget Partnership each dispense with public surveys and instead uses in-country experts to evaluate "the opposite of corruption" -- which Global Integrity defines as the public policies that prevent, discourage or expose corruption.[31] These approaches compliment the first wave, awareness-raising tools by giving governments facing public outcry a checklist which measures concrete steps toward improved governance.[32]

Typical second wave corruption metrics do not offer the worldwide coverage found in first wave projects, and instead focus on localizing information gathered to specific problems and creating deep, "unpackable" content that matches quantitative and qualitative data. Meanwhile, alternative approaches such as the British aid agency's Drivers of Change research skips numbers entirely and favors understanding corruption via political economy analysis of who controls power in a given society.[33]

[edit] Corruption in different regions

| This section requires expansion. |

[edit] Africa

[edit] Asia

- India

- Vietnam

- Philippines

[edit] Europe

- United Kingdom

- France

- Italy

[edit] North America

[edit] Canada

[edit] United States

Keith Olbermann of MSNBC listed in the show Countdown with Keith Olbermann the "top 25 financially corrupt U.S. politicians" (worst first): William Marcy Tweed; Rod Blagojevich Illinois gov; Charles R. Forbes, Harding's choice for Veteran's Bureau; Vice-President Schuyler Colfax; California Congressman Randall Harold Cunningham; Florida Congressman Richard Kelly; Spiro Agnew, Nixon's vice president; Albert Fall, Secretary of the Interior for Harding; Simon Cameron, President Lincoln's first Secretary of War; Kentucky Congressman Andrew Jackson May; Congressman J. Parnell Thomas; House Speaker Jim Wright; Illinois Governor Otto Kerner; Dusty Foggo; William Belknap, Secretary of War; Orville Babcock, secretary to President Grant; mayor of New York Jimmy Walker; Ohio Congressman James Traficant; Richard Nixon; Illinois Dan Rostenkowski; Chairman of the House Administration Committee, Wayne Hays; Governor George Ryan; Senator Ted Stevens of Alaska; and Arkansas Congressman Tommy Robinson. [3]

- Political scandals of the United States

- Bootleggers and Baptists phenomenon in Kentucky, when intentional

- Dixie Mafia when involving members of local law enforcement

- Hired Truck Program

- Iran-Contra Affair

- Jack Abramoff Indian lobbying scandal

- Rampart Scandal

- Rod Blagojevich corruption charges

[edit] South America

[edit] International

[edit] See also

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Political corruption |

[edit] Forms or aspects of corruption

[edit] Good governance

[edit] Theoretical aspects

[edit] Anti-corruption authorities and measures

- GEMAP

- Independent Commission Against Corruption

- Inter-American Convention Against Corruption

- United Nations Convention against Corruption

[edit] Corruption in fiction

- The Financier (1912), The Titan (1914), and The Stoic (1947), Theodore Dreiser's Trilogy of Desire, based on the life of the notorious transit mogul Charles Tyson Yerkes

- Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

- Atlas Shrugged (1957 novel)

- Henry Adams's novel Democracy (1880)

- Carl Hiaasen's novel Sick Puppy (1999)

- Much of the Batman comic book series

- V for Vendetta comic book series

- The Ghost in the Shell Anime films and series

- Animal Farm a novel by George Orwell

- Training Day (2001 film)

- Exit Wounds (2001 film)

- American Gangster (2007 film)

[edit] References

- ^ African corruption 'on the wane', 10 July 2007, BBC News

- ^ Nigeria's corruption busters

- ^ New Statesman - When the money goes west

- ^ "Will Growth Slow Corruption In India?". Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/2007/08/15/wipro-tata-corruption-ent-law-cx_kw_0814whartonindia.html.

- ^ Ukraine remembers famine horror

- ^ "How common is bribe-paying?". http://www.transparency.org/news_room/latest_news/press_releases/2005/09_12_2005_barometer_2005. "...a relatively high proportion of families in a group of Central Eastern European, African, and Latin American countries paid a bribe in the previous twelve months."

- ^ Kentucky's unholy alliance

- ^ O'Toole, Patricia, "The War of 1912," TIME in Partneship with CNN, Jun. 25, 2006.

- ^ Roosevelt, Theodore. An Autobiography: XV. The Peace of Righteousness, Appendix B, NEW YORK: MACMILLAN, 1913.

- ^ AsiaMedia :: Right to Information Act India's magic wand against corruption

- ^ Western bankers and lawyers 'rob Africa of $150bn every year

- ^ Why benchmarking works - PSD Blog - World Bank Group

- ^ http://www.adelaide.edu.au/cies/0320.pdf

- ^ http://www.heritage.org/Index/chapters/pdf/Index2000_Chap3.pdf Economic Freedom and Corruption (pdf), Alejandro A. Chafuen and Eugenio Guzmán

- ^ http://www.heritage.org/Index/chapters/pdf/Index2000_Chap3.pdf Economic Freedom and Corruption (pdf), Alejandro A. Chafuen and Eugenio Guzmán

- ^ http://www.heritage.org/Index/chapters/pdf/Index2000_Chap3.pdf Economic Freedom and Corruption (pdf), Alejandro A. Chafuen and Eugenio Guzmán

- ^ Project Syndicate

- ^ Privatization in Competitive Sectors: The Record to Date. Sunita Kikeri and John Nellis. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 2860, June 2002. [1] Privatization and Corruption. David Martimort and Stéphane Straub. [2]

- ^ Who wants to be a millionaire? - An online collection of Nigerian scam mails

- ^ Nigeria's corruption totals $400 billion

- ^ USATODAY.com - Fidel Castro net worth rises, according to 'Forbes'

- ^ Ben Shapiro :: Townhall.com :: The death of Fidel Castro

- ^ A Users' Guide to Measuring Corruption.

- ^ Galtung, Fredrik (2006). "Measuring the Immeasurable: Boundaries and Functions of (Macro) Corruption Indices," in Measuring Corruption, Charles Sampford, Arthur Shacklock, Carmel Connors, and Fredrik Galtung, Eds. (Ashgate): 101-130.

- ^ Sik, Endre (2002). "The Bad, the Worse and the Worst: Guesstimating the Level of Corruption," in Political Corruption in Transition: A Skeptic's Handbook, Stephen Kotkin and Andras Sajo, Eds. (Budapest: Central European University Press): 91-113.

- ^ Galtung, Fredrik (2006). "Measuring the Immeasurable: Boundaries and Functions of (Macro) Corruption Indices," in Measuring Corruption, Charles Sampford, Arthur Shacklock, Carmel Connors, and Fredrik Galtung, Eds. (Ashgate): 101-130.

- ^ Arndt, Christiane and Charles Oman (2006). Uses and Abuses of Governance Indicators (Paris: OECD Development Centre).

- ^ Media citing Transparency International

- ^ A Decade of Measuring the Quality of Governance.

- ^ A Users' Guide to Measuring Corruption.

- ^ Global Integrity Report: Methodology

- ^ A Users' Guide to Measuring Corruption.

- ^ A Users' Guide to Measuring Corruption.

[edit] Further reading

- Alexandra Wrage (2007) Bribery and Extortion: Undermining Business, Governments and Security

- Axel Dreher, Christos Kotsogiannis, Steve McCorriston (2004), Corruption Around the World: Evidence from a Structural Model.

- Kimberly Ann Elliott, ed, Corruption and the Global Economy (1997)

- Edward L. Glaeser and Claudia Goldin, eds, Corruption and Reform: Lessons from America's Economic History U. of Chicago Press, 2006. 386 pp. ISBN 0-226-29957-0.

- Arnold J. Heidenheimer, Michael Johnston and Victor T. LeVine (eds), Political Corruption: A Handbook (1989) 1017 pages.

- Michael Johnston. Syndromes of Corruption: Wealth, Power, and Democracy (2005)

- Johann Graf Lambsdorff (2007), The Institutional Economics of Corruption and Reform: Theory, Evidence and Policy Cambridge University Press

[edit] External links

- United Nations Convention against Corruption at Law-Ref.org - fully indexed and crosslinked with other documents

- World Bank anti-corruption page

- World Bank's Worldwide Governance Indicators Worldwide ratings of country performances on six governance dimensions from 1996 to present.

- Corruption Literature Review World Bank Literature Review.

- UNICORN: A Global Trade Union Anti-corruption Network, based at Cardiff University