Haussmann's renovation of Paris

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2009) |

The Haussmann Renovations, or Haussmannisation of Paris, was a work commissioned by Napoléon III and led by the Seine prefect, Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann between 1852 and 1870, though work continued well after the Second Empire's demise in 1870.

The project encompassed all aspects of urban planning, both in the centre of Paris and in the surrounding districts: streets and boulevards, regulations imposed on facades of buildings, public parks, sewers and water works, city facilities and public monuments.

Haussmann's approach to urban planning was strongly criticised by some of his contemporaries, ignored for a good part of the twentieth century, but later re-evaluated when modernist approaches to urban planning became discredited. His restructuring of Paris gave its present form; its long straight, wide boulevards with their cafés and shops determined a new type of urban scenario and have had a profound positive productive influence on the everyday lives of Parisians. Haussmann's boulevards established the foundation of what is today the popular representation of the French capital around the world, by cutting through the old Paris of dense and irregular medieval alleyways into a rational city with wide avenues and open spaces which extended outwards far beyond the old city limits.

[edit] A medieval capital is modernized

In the middle of the nineteenth century, the centre of Paris had the same structure as it did in the Middle Ages. The narrow interweaving streets and cramped buildings impeded the flow of traffic, resulting in unhealthy conditions[1] that were denounced by the first hygiene scientists.[citation needed] The successive regimes[specify] had pushed the outer limits of the city to where they are today, on the Paris périphérique (beltway), but none of them changed the heart of the capital. From the 1830s to 1860s, it was much the same.

[edit] Modernization of a medieval city

The plan to modernise the city dates back to revolutionary times. In 1794, during the French Revolution, a "Commission of Artists" formed a project suggesting the opening of broader avenues in Paris, with a street making a straight line from Place de la Nation to the Louvre, where the Avenue Victoria is today. It anticipated the east-west main line and attempted to highlight the public monuments.[specify]

Napoleon I commissioned the construction of a colossal street along the Jardin des Tuileries, the Rue de Rivoli, that extended under the Second Empire up to the Châtelet and the Rue Saint-Antoine; the new street was better adapted to traffic than the street designed by the Commission of Artists. It also served as the basis for a new legal tool: the servitude d'alignement, which prevented real estate owners from renovating or rebuilding beyond a certain line drawn by the administration.[specify] However, the law's objective of eventually widening the streets was not borne out.

At the end of the 1830s, prefect Rambuteau realised that the problems regarding traffic and hygiene in the old over-populated districts had become a cause for concern; in accordance with the miasma theory of disease, then prevailing, it was important to "let air and men circulate". This conclusion stemmed from the 1832 cholera epidemic—which killed 20,000 in Paris out of a total population of 650,000[1]—and the new "social medicine" famously analysed by Michel Foucault[citation needed] (which focused on flux, circulation of air, location of cemeteries, etc.) Prefect Rambuteau thus drew a new street in the medieval centre of Paris, but the administration had limited powers due to the prevailing rules regulating expropriation. A new law passed on 3 May 1841 attempted to solve this issue.

It was with this background that the Second Empire opted for a huge program of expropriation and clearances, much more costly than the servitude d'alignement, but also much more effective.

[edit] Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte

Elected president of the Republic of France in 1848, Napoléon III became emperor on 2 December 1852. Under his new rank, Napoléon III decided to modernize Paris after seeing London, a city transformed by the Industrial Revolution, which offered large public parks and a complete sewer system. Inspired by Rambuteau's ideas, and aware of social issues, he wished to improve the housing conditions of the lower class; in some neighbourhoods, the population density reached numbers of 100,000 people/km2 (250,000 people/sq. mile) in conditions of very poor sanitation. The goal was also for public authority to better control a capital where several regimes had been overthrown since 1789. Some real-estate owners demanded large, straight avenues to help troops manoeuvre.[2]

To satisfy his ambitions the new emperor had a considerable amount of power at his disposal, enabling him to shrug off any resistance, something his predecessors had lacked.

But Napoleon III still had to find a man capable of carrying out a project of such magnitude. He found such a man in Georges Eugène Haussmann, a man of action and rigour, known for being methodical, and he nominated him Prefect of the Seine in 1853. The two men formed an efficient team, the emperor supporting the prefect against his adversaries, and Haussmann showing loyalty in all circumstances, while promoting his own ideas such as a project for Boulevard Saint-Germain.

Such considerable work required many different collaborators. Victor de Persigny, Minister of the Interior, who had introduced Haussmann to Napoleon, was put in charge of the financial aspects, with the help of the Pereire brothers. Jean-Charles Alphand dealt with the parks and plantations of gardener Jean-Pierre Barillet-Deschamps. Haussmann emphasised the fundamental role of the Paris Map services, led by the architect Deschamps who was in charge of drawing the new avenues and enforcing the construction rules; in this area, "geometry and graphic design play a more important role than architecture itself", said Haussmann,[3]. Other architects took part in the project: Victor Baltard at Les Halles, Théodore Ballu for the Church of Trinity, Gabriel Davioud for the theatres on the Place du Châtelet, and veteran Jacques Ignace Hittorff for the Gare du Nord.

[edit] Collaboration between public regulation and private initiatives

Inspired by Saint-Simonism, Napoleon III, and engineers such as Michel Chevalier or entrepreneurs like the Pereire brothers, believed that society could be transformed and poverty reduced by economic voluntarism, according to which the government should play an important part in economic affairs. It took a strong or even authoritarian regime to encourage capitalists in launching important projects that would benefit society as a whole, and particularly the poor. The heart of the economic system were the banks, which at the time underwent considerable expansion. The renovations of Paris matched this political orientation perfectly. Haussmann's projects would hence be decided and managed by the state, carried out by private entrepreneurs and financed with loans backed by the state.

[edit] The Haussmann system

In a first step, the state expropriated those owners whose land stood in the way of the renovations. Jules Ferry condemned this financial issue in a pamphlet published in 1867: Les comptes fantastiques d'Haussmann (the title is a pun, translating as The fantastic accounts of Haussmann, but homophonic with Jacques Offenbach's comical opera, Les contes d'Hoffmann).[4]

[edit] Public regulations

Haussmann had the opportunity of working in a legislative and regulatory context that was modified specifically for the renovations. The decree of 26 March 1852 regarding the streets of Paris, passed one year before Haussmann's appointment, established the main judicial tools:

- Expropriation "for purposes of public interest": the city could acquire buildings placed along the avenues to be constructed, whereas earlier it could only acquire the buildings placed directly on the future construction site. This would allow a considerable part of the Île de la Cité to be demolished. After 1860, the regime's more progressive stance made expropriations more difficult.

- Those who owned buildings were required to clean and refresh the facades every ten years.

- The levelling of the streets of Paris, the buildings' alignments and connections to the sewer were regulated.

The authorities intervened at the same time to regulate the dimensions of buildings and even on the aesthetic aspect of their frontages:

- The 1859 regulations for urban planning in Paris increased the maximum height of buildings from 17.55 meters (57.5 ft) to 20 meters (65.6 ft) in streets wider than 20 meters. The roofs needed to still have a 45 degree incline.

- Construction along the new avenues had to comply with a set of rules regarding outside appearance. Neighbouring buildings had to have their floors at the same height, and the façades' main lines had to be the same. The use of quarry stone was mandatory along these avenues. Paris started to acquire the features of an immense palace.

Already, the central role played by the architects of the roads showed the importance of engineers as civil servants.

[edit] The plan unfolds

The plans were a reflection of the Empire's evolution: authoritarian until 1859, and more flexible after 1860. 20,000 houses were destroyed, and over 40,000 built between 1852 and 1872.

Some of these projects were to continue under the Third Republic, after Haussmann and Napoleon III had stepped down.

[edit] A network of large avenues

When Rambuteau cleared the way for the first time in the city's history for a large avenue in the centre of Paris, Parisians were surprised by its width of 13 meters (45 ft). But Haussmann made the Rue Rambuteau a moderate-sized street after creating new avenues up to 30 meters wide (100 ft). To this day, the Haussmann network is still the backbone of Paris' urban body.

[edit] The north-south and east-west openings

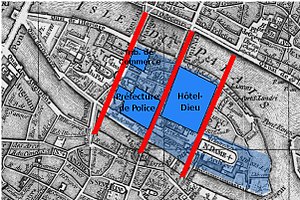

Between 1854 and 1858, Haussmann took advantage of what was to be the most authoritarian period in Napoleon III's rule to achieve what possibly no other decade could have: transforming the heart of Paris by clearing a gigantic crossing in its centre. [5]

Because of the construction of the North-South line, from boulevard de Sébastopol to Boulevard Saint-Michel, a number of alleyways and dead-ends were cleared from the map. This line included an important intersection near the Châtelet and the Rue de Rivoli: the Second Empire extended it to the rue Saint-Antoine, a street Napoleon I had drawn alongside the Tuileries.

At the same time, Baltard was working on the Halles, a project initiated by Rambuteau, and the Île de la Cité was vastly demolished and transformed. The bridges surrounding were either rebuilt or considerably redone.

Haussmann completed this large intersection with line connecting the first circle of boulevards, such as the rue de Rennes on the left bank and the avenue de l'Opéra on the right bank. The rue de Rennes, which was meant to reach the Seine, never did.

[edit] The rings of boulevards are completed

Haussmann carried on the work of Louis XIV. He widened the Grands Boulevards and designed and built new axes of great size such as the Boulevard Richard-Lenoir.

Some of these axes connected Louis XIV's grand boulevards to those that ran alongside the Farmers General Wall. The Boulevard Haussmann and the Rue La Fayette, partially in place before 1870, guaranteed better access to the Opera neighbourhood from the outside districts. The Boulevard Voltaire made it easier to bypass the centre from the Place de la Nation.

On the Left Bank, as the Southern Boulevards, which go through Place d'Italie, Place Denfert-Rochereau and Montparnasse, were too far from the centre, the idea of another east-west access arose. Haussmann added the Rue des Écoles, designed by Napoléon III to his pet project: the Boulevard Saint-Germain, a Left Bank extension of the Grands Boulevards of the Right Bank.

[edit] A third network: the outside arrondissements

In the last years of his term, Haussmann began to imagine turning the outside towns annexed in 1860 into arrondissements (districts). He decided to create a long, winding set of streets connecting the 12th, 19th, and 20th arrondissements: rue Simon-Bolivar, rue des Pyrénées, and avenue Michel-Bizot. The western neighbourhoods enjoy a prestigious set-up, with twelve avenues, most of them built during the Second Empire, converging to the place de l'Étoile.

Other lines, such as the avenue Daumesnil and the boulevard Malesherbes, enabled access to the centre from the outside arrondissements.

[edit] The squares at the crossroads

The connection between the great boulevards required the creation of squares on the same scale. The Châtelet, converted by Davioud, is the crossroads of the two great axes crossing Paris from north to south and east to west. The works of Haussmann converted other great squares at crossing points across the whole city: Place de l'Étoile, Place Léon-Blum, Place de la République, Place de l'Alma.

[edit] The railway stations

Haussmann had the Gare de Lyon constructed in 1855 and the Gare du Nord in 1865.

He dreamed of connecting the Parisian railway termini with rail links but had to be content with making access easy by connecting them with important roads. From the Gare de Lyon, the Rue de Lyon, the Boulevard Richard-Lenoir and the Boulevard de Magenta run to the Gare de l'Est. Two parallel axes (Rue La Fayette and Boulevard Haussmann is the first, Rue de Châteaudun and Rue de Maubeuge the second) join the district around the Gare de l'Est and the Gare du Nord to that of the Gare Saint-Lazare. On the Left Bank, the Rue de Rennes serves Gare Montparnasse, then situated where the Tour Montparnasse stands today.

[edit] Monuments

Napoléon III and Haussmann covered the town with prestigious edifices. Charles Garnier constructed the Opéra Garnier in an eclectic style and Gabriel Davioud designed two symmetric theatres on the Place du Châtelet. L'Hôtel-Dieu, the prison of the Cité (and future police headquarters), and the tribunal of Commerce replaced the medieval districts on the Île de la Cité. Each of the twenty new local government districts (arrondissements) was given a town hall.

They took care to set these monuments in the town by creating vast perspectives. For example the Avenue de l'Opéra offers a great frame for the edifice of the Opera Garnier, while the houses that prevented contemplation of the cathedral of Notre-Dame gave way to a great open space.

[edit] Modern public facilities

The renovation of Paris was meant to be total. Cleaning up living areas implied not only a better air circulation but also better provision of water and better evacuation of waste.

In 1852, drinking water in Paris came mainly from the Ourcq, a tributary of the Marne. Steam engines also extracted water from the Seine, but the hygiene was appalling. Haussmann tasked the engineer Belgrand with the creation a new system of water provisioning to the capital, which lead to the construction of 600 kilometres of aqueduct between 1865 and 1900. The first, that of the Dhuis, brought water extracted near Château-Thierry. These aqueducts discharged their water in reservoirs situated within the city. Inside the city limits and opposite Parc Montsouris, Belgrand built the largest water reservoir in the world to hold the water from the River Vanne.

[edit] Green spaces

Green spaces in Paris were rare. Having visited and enjoyed the beautiful and plentiful London parks, Napoléon III hired engineer Jean-Charles Alphand, Haussmann's future successor, to create expansive parks and green spaces. On the east and west borders of the city, you could find the bois de Boulogne and the bois de Vincennes, respectively. In the enceinte de Thiers, the Parc des Buttes Chaumont, the parc Monceau, and the parc Montsouris offered citizens beautiful scenery and a place to relax and be with nature. Also, in each district squares were built, and trees were planted along avenues.

[edit] Paris expands

In 1860, Paris absorbed the communities outside its gates up to the enceinte de Theirs. The old twelve arrondissements became the new twenty arrondissements. See also Arrondissements of Paris.

[edit] Critics of Napoleon III's urban politics

Artists and architects (Charles Garnier) deplored the suffocating monotony of monumental architecture. Politicians and writers accused the spread of speculation and corruption (Émile Zola's "La Curée" ) and a few wrongly accused Haussmann of personal enrichment. Many of the criticisms targeted the base motivations of the venture and ended by felling the préfet.

[edit] Widening of streets: a tool for an authoritarian regime?

Many of Napoléon III's contemporaries accused him of hiding, under the guise of improving social and sanitary conditions, a project geared toward more effective military policing of the capital. Under this theory the wide thoroughfares were constructed to facilitate troop movement and prevent easy blocking of streets with barricades, and their straightness allowed artillery to fire on rioting crowds and their barricades. This interpretation has been widely repeated and accepted, notably in Lewis Mumford's writings.

The extent of the work itself shows that Napoleon III's aims were, at least, not solely security-oriented in nature. Beyond the spectacular piercing of the main boulevards, city transformations also included the construction of a modern underground network of sewers and freshwater, the installation of an efficient building plan on the surface, and the harmonisation of the architecture along the new avenues.

Yet it is true that Napoleon III was concerned with maintaining strict order. Haussmann never hesitated to explain that his street plan would ease the maintenance of public order when presenting his projects to the Conseil de Paris or local landowners. It should also be noted that when reports of the outbreak of the Paris Commune insurrection reached Haussmann he expressed his frustration at not having been able to carry out his reforms quickly enough to make such an insurrection futile. The strategic dimension is thus indeed present, but it is but one element among others; it is perhaps most important where there was question of joining Paris' main casernes between them.

It should also be mentioned that the police were not one of Haussmann's responsibilities. His mandate actually reduced the position of préfet de police, as it removed from this office problems such as city hygiene and the lighting and cleaning of its streets.

[edit] Social rupture

Many contemporary observers denounced the demographic and social effects of Haussmann's urbanism operations.

Louis Lazare, author, under Haussmann's predecessor Rambuteau, of an important "dictionary of Paris streets", considered in 1861 in the journal Revue municipale that Haussmann's works disproportionately increased State-dependent populations in attracting masses of poor to Paris. In reality, in certain respects Haussmann himself slowed the progress of his renovations in order to avoid a massive flood of workers to the Capital.

On the other hand, critics denounced as early as 1850 the effect that the renovations would have on the social composition of Paris. In a slightly oversimplified way, they painted a portrait of the pre-Haussmannian building as a synthesis of the Parisian social hierarchy: the bourgeoisie on the second floor, civil servants and employees on the third and fourth, low-wage employees on the fifth, house staff, students and the poor under the eaves. Thus one building was shown to represent and house all social classes. This cohabitation, of course varying from quarter to quarter, disappeared in its majority after the completion of Haussmann's work. This had two effects on the dispersion of dwellings in Paris:

- The city-centre renovations provoked a rise in rents, and this forced poorer families towards Paris' outer arrondissements. This we can see in population statistics:

| Arrondissement | 1861 | 1866 | 1872 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1er | 89,519 | 81,665 | 74,286 |

| 6e | 95,931 | 99,115 | 90,288 |

| 17e | 75,288 | 93,193 | 101,804 |

| 20e | 70,060 | 87,844 | 92,712 |

- Certain urbanism decisions contributed to a social imbalance between the Paris' west, wealthy, and its east, underprivileged. Therefore no eastern neighborhood in Paris benefited from renovations comparable to the large avenues surrounding the place de l'Étoile in the XVIe and XVIIe arrondissements. The poor were concentrated in arrondissements left aside by the city renovations.

As an answer to this, Haussmann presented the complex creation of the bois de Vincennes forest-parklands that would give working populations a promenade comparable to the bois de Boulogne. It also must be noted that the unsanitary quarters "cleaned" by Haussmann contained very few of the bourgeois class. Indeed, the parting of uprooting of established working-class residential areas may have been another security measure, as a disrupted and scattered community will find it harder to unite and so will pose less of a threat. To the modern ears this may sound odd, but the working-class people were still known as "the dangerous classes" to Parisians, and the French in general, and the memories of the 1789 and 1848 revolutions, where workers revolted against the state, had left deep impressions on the Parisian psyche.

That way, a sort of "zonage" was established that still dominates the distribution of housing and activities in Paris and its nearest suburbs: from the centre to the west, offices and wealthy neighborhoods; from the east and outer rim, poorer housing and industry.

[edit] Financial crisis

The financial system funding the renovations began to fail towards the end of the 1860s. Paris' annexation of its intra-muros suburbs at the beginning of the decade came at a high price: Paris' newer outer quarters required even more renovations than the still-incomplete city centre, and the budgets prepared before the work's onset were proven to be way below the mark. Also, a loosening of the regime's more authoritarian aspects made obtaining the necessary expropriations more difficult, as the Conseil d'État (State Council) and Cour de cassation (appeals court) often intervened in favour of landowners.

In addition to the above, Parisians were becoming intolerant of the renovations that had paralysed the city for nearly twenty years. Also, the utility of the network of boulevards in the outer quarters was not as obvious as the piercing of, for example, the boulevard de Sébastopol or the boulevard Saint-Germain.

The journalist Jules Ferry made a name for himself through a series of articles titled "Les Comptes fantastiques d'Haussmann" (or "Haussmann's fantastical accounts (tales)") in which he denounced the exaggerated ambitions of the renovation projects and their uncertain finances. These projects were effectively financed not by loan, but by bonds sold through the Caisse des travaux de Paris (Paris works fund) quite outside of parliament control.

Haussmann was removed from office in the beginning of 1870, a few months before the end of the 2nd Empire he had served for its almost entire duration. The debts incurred were quickly absorbed by the government of the 3rd Republic.

[edit] The impact of Paris' renovations

[edit] Aesthetics of the "Street-Wall"

"Hausmannism", a perfectionist art, was not satisfied with tracing new streets and utilities. It also intervened in the aesthetic aspects of the habitable building.

The block is designed as a homogeneous architectural one. The building is not treated as an independent structure, but must make, with the other buildings in its block, if not with all others in the same street or quarter, a unified urban landscape.

The regulations and constraints imposed by the authorities favoured a typology that brings the classical evolution of the Parisian building to its term in the façade typical of the Haussmann era:

- ground floor and 'between floors' with thick, usually street-lateral, bearing walls

- second "noble" floor having one or two balconies; third and fourth floor in the same style but a less elaborate stonework around the windows;

- fifth floor with a unique continuous undecorated balcony;

- eaves angled at 45º.

The Haussmannian façade is organised around horizontal lines that often continue from one building to the next: balconies, cornices are perfectly aligned without any noticeable alcoves or projections. At the risk of the 'uniformisation' of certain quarters, the rue de Rivoli served as a model for the entire network of new Parisian boulevards. For the building façades, the technological progress of stone sawing and (steam) transportation allowed the use of massive stone blocks instead of simple stone facing. The street-side result was a "monumental" effect that exempted buildings from a dependence on decoration; sculpture and other elaborate stonework would not become widespread until the end of the century.

[edit] Legacy

The Baron Haussmann's transformations to Paris brought a real improvement to the quality of life in the capital. Disease epidemics ceased, traffic circulation improved and new buildings are better-built and more functional than their predecessors.

The Second Empire renovations left such a mark on Paris' urban history that all posterior trends and influences were forced to refer to them, to adapt or reject them, or to recuperate certain of its elements.

The end of "pure Haussmannism" can be traced to urban legislation of 1882 and 1884 that broke with the uniformity of the classical street, in permitting staggered facades and the first fantasy roof-level architecture; the latter would develop greatly after restrictions were further loosened in a 1902 law. All the same, this period but amounts to a "post-Haussmann" period that rejected only the austerity of the napoleon-era architecture without any criticism towards the planning of streets and islands themselves.

A century after Napoleon III's reign, the rise of a new voluntarist Fifth Republic opened a new era of Parisian urbanism. The new era rejected Haussmannian ideas as a whole to embrace those represented by architects such as Le Corbusier in abandoning unbroken street-side facades, limitations in building size and dimension, and even abandoning the street itself to automobiles with the creation of separated, car-free spaces between the buildings for pedestrians. This new model was quickly brought into question by the 1970s, a period marked a rediscovery of the Haussmanian heritage: a new promotion of the multifunctional street was accompanied by limitations in the building model and, in certain quarters, by an attempt to rediscover the architectural homogeneity of the Second Empire street-block.

Today's Parisian public holds a positive view of the Haussmann legacy, to a point where certain suburban towns, for example Issy-les-Moulineaux or Puteaux, have built new quarters that claim even in their name, "Quartier Haussmannian", the Haussmanian heritage. These quarters are in reality but a pastiche of early 20th century post-Haussmann architecture with its bow windows and loggias.

[edit] See also

[edit] References

This article has been translated from its equivalent in the French language Wikipedia.

- ^ Haussmann's Architectural Paris - The Art History Archive, checked October 21st 2007.

- ^ Letter written by owners from the neighbourhood of the Pantheon to prefect Berger in 1850, quoted in the Atlas du Paris Haussmannien

- ^ Mémoires du Baron Haussmann

- ^ Jules Ferry, Les comptes fantastiques d'Haussmann (Gallica).

- ^ We Built This City: Paris. Documentary. (2003) http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0902351/