Addison's disease

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| It has been suggested that Autoimmune adrenalitis be merged into this article or section. (Discuss) |

| Addison's disease Classification and external resources |

|

| ICD-10 | E27.1-E27.2 |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 255.4 |

| DiseasesDB | 222 |

| MedlinePlus | 000378 |

| eMedicine | med/42 |

| MeSH | D000224 |

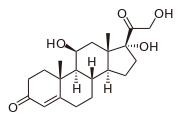

Addison's disease (also known as chronic adrenal insufficiency, hypocortisolism or hypocorticism) is a rare endocrine disorder in which the adrenal gland doesn't produce enough steroid hormones (glucocorticoids and often mineralocorticoids).[1] It may develop in children and adults, and may occur as the result of many underlying causes.

The condition is named after Dr Thomas Addison, the British physician who first described the condition in his 1855 publication On the Constitutional and Local Effects of Disease of the Suprarenal Capsules.[2] The adjective "Addisonian" is used for features of the condition, as well as patients with Addison's disease.[3]

The condition is generally diagnosed with blood tests, medical imaging and additional investigations.[3] Treatment involves replacement of the hormones (oral hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone). If the disease is caused by an underlying problem, it may be possible to address that. Regular follow-up and monitoring for other health problems is necessary.[3]

While Addison's six patients in 1855 all had adrenal tuberculosis,[4] the term "Addison's disease" does not imply an underlying disease process.

Contents |

[edit] Signs and symptoms

[edit] Symptoms

The symptoms of Addison's disease develop insidiously, and it may take some time to be recognized. The most common symptoms are fatigue, muscle weakness, weight loss, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, sweating, changes in mood and personality, and joint and muscle pains. Some have marked cravings for salt or salty foods due to the urinary losses of sodium.[3] Adrenal insufficiency is manifested in the skin primarily by hyperpigmentation.[5]

[edit] Clinical signs

On examination, the following may be noticed:[3]

- Low blood pressure that falls further when standing (orthostatic hypotension)

- Most people with primary Addison's have darkening (hyperpigmentation) of the skin, including areas not exposed to the sun; characteristic sites are skin creases (e.g. of the hands), nipples, and the inside of the cheek (buccal mucosa), also old scars may darken. This occurs because melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) shares the same precursor molecule as adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH); an increase in ACTH production also increases MSH. In secondary and tertiary forms of Addison's, skin darkening does not occur.

- Signs of conditions that often occur together with Addison's: goiter and vitiligo

[edit] Addisonian crisis

An "Addisonian crisis" or "adrenal crisis" is a constellation of symptoms that indicate severe adrenal insufficiency. This may be the result of either previously undiagnosed Addison's disease, a disease process suddenly affecting adrenal function (such as adrenal hemorrhage), or an intercurrent problem (e.g. infection, trauma) in the setting of known Addison's disease. Additionally, this situation may develop in those on long-term oral glucocorticoids who have suddenly ceased taking their medication. In these people, long term use of synthetic glucocorticoids will have caused further atrophy of the adrenal glands by negative feedback. It is also a concern in the setting of myxedema coma; thyroxine given in that setting without glucocorticoids may precipitate a crisis.

Untreated, an Addisonian crisis can be fatal. It is a medical emergency, usually requiring hospitalization. Characteristic symptoms are:[6]

- Sudden penetrating pain in the legs, lower back or abdomen

- Severe vomiting and diarrhea, resulting in dehydration

- Low blood pressure

- Loss of consciousness/Syncope

- Hypoglycemia

- Confusion, psychosis

- Severe lethargy

- Hypercalcemia

- Convulsions

- Fever

[edit] Diagnosis

[edit] Suggestive features

Routine investigations may show:[3]

- Hypercalcemia

- Hypoglycemia, low blood sugar (worse in children)

- Hyponatraemia (low blood sodium levels), due to loss of production of the hormone aldosterone

- Hyperkalemia (raised blood potassium levels), also due to loss of production of the hormone aldosterone

- Eosinophilia and lymphocytosis (increased number of eosinophils or lymphocytes, two types of white blood cells)

- Metabolic acidosis (increased blood acidity), also due to loss of the hormone aldosterone because sodium reabsorption in the distal tubule is linked with acid/hydrogen ion (H+) secretion. Low levels of aldosterone stimulation of the renal distal tubule leads to sodium wasting in the urine and H+ retention in the serum.

[edit] Testing

In suspected cases of Addison's disease, one needs to demonstrate that adrenal hormone levels are low even after appropriate stimulation (called the ACTH stimulation test) with synthetic pituitary ACTH hormone tetracosactide . Two tests are performed, the short and the long test.

The short test compares blood cortisol levels before and after 250 micrograms of tetracosactide (IM/IV) is given. If, one hour later, plasma cortisol exceeds 170 nmol/L and has risen by at least 330 nmol/L to at least 690 nmol/L, adrenal failure is excluded. If the short test is abnormal, the long test is used to differentiate between primary adrenal failure and secondary adrenocortical failure.

The long test uses 1 mg tetracosactide (IM). Blood is taken 1, 4, 8, and 24 hours later. Normal plasma cortisol level should reach 1000 nmol/L by 4 hours. In primary Addison's disease, the cortisol level is reduced at all stages whereas in secondary corticoadrenal insufficiency, a delayed but normal response is seen.

Other tests that may be performed to distinguish between various causes of hypoadrenalism are renin and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels, as well as medical imaging - usually in the form of ultrasound, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

[edit] Causes

Causes of adrenal insufficiency can be grouped by the way in which they cause the adrenals to produce insufficient cortisol. These are adrenal dysgenesis (the gland has not formed adequately during development), impaired steroidogenesis (the gland is present but is biochemically unable to produce cortisol) or adrenal destruction (disease processes leading to the gland being damaged).[3]

[edit] Adrenal dysgenesis

All causes in this category are genetic, and generally very rare. These include mutations to the SF1 transcription factor, congenital adrenal hypoplasia (AHC) due to DAX-1 gene mutations and mutations to the ACTH receptor gene (or related genes, such as in the Triple A or Allgrove syndrome). DAX-1 mutations may cluster in a syndrome with glycerol kinase deficiency with a number of other symptoms when DAX-1 is deleted together with a number of other genes.[3]

[edit] Impaired steroidogenesis

To form cortisol, the adrenal gland requires cholesterol, which is then converted biochemically into steroid hormones. Interruptions in the delivery of cholesterol include Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome and abetalipoproteinemia.

Of the synthesis problems, congenital adrenal hyperplasia is the most common (in various forms: 21-hydroxylase, 17α-hydroxylase, 11β-hydroxylase and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase), lipod CAH due to deficiency of StAR and mitochondrial DNA mutations.[3] Some medications interfere with steroid synthesis enzymes (e.g. ketoconazole), while others accelerate the normal breakdown of hormones by the liver (e.g. rifampicin, phenytoin).[3]

[edit] Adrenal destruction

Autoimmune adrenalitis can be a cause of Addison's disease. Autoimmune destruction of the adrenal cortex (often due to antibodies against the enzyme 21-Hydroxylase) is a common cause of Addison's in teenagers and adults. This may be isolated or in the context of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome (APS type 1 or 2).

Adrenal destruction is also a feature of adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), and when the adrenal glands are involved in metastasis (seeding of cancer cells from elsewhere in the body), hemorrhage (e.g. in Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome or antiphospholipid syndrome), particular infections (tuberculosis,[7] histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis), deposition of abnormal protein in amyloidosis.

[edit] Treatment

[edit] Maintenance treatment

Treatment for Addison's disease involves replacing the missing cortisol, usually in the form of hydrocortisone tablets, in a dosing regimen that mimics the physiological concentrations of cortisol. Alternatively one quarter as much prednisolone may be used for equal glucocorticoid effect as hydrocortisone. Treatment must usually be continued for life. In addition, many patients require fludrocortisone as replacement for the missing aldosterone. Caution must be exercised when the person with Addison's disease becomes unwell, has surgery or becomes pregnant. Medication may need to be increased during times of stress, infection, or injury.

[edit] Epidemiology

The frequency rate of Addison's disease in the human population is sometimes estimated at roughly 1 in 100,000.[8] Some research and information sites put the number closer to 40-60 cases per 1 million population. (1/25,000-1/16,600)[9] (Determining accurate numbers for Addison's is problematic at best and some incidence figures are thought to be underestimates.[10]) Addison's can afflict persons of any age, gender, or ethnicity, but it typically presents in adults between 30 and 50 years of age. Young women are most affected, outnumbering men by a factor of four.[11] Research has shown no significant predispositions based on ethnicity.[9]

[edit] Prognosis

While treatment solutions for Addison's disease are far from precise, overall long-term prognosis is typically good. Because of individual physiological differences, each person with Addison's must work closely with their physician to adjust their medication dosage and schedule to find the most effective routine. Once this is accomplished (and occasional adjustments must be made from time to time, especially during periods of travel, stress, or other medical conditions), symptoms are usually greatly reduced or occasionally eliminated so long as the person continues their dosage schedule.

[edit] Canine hypoadrenocorticism

The condition is relatively rare, but has been diagnosed in all breeds of dogs. In general, it is underdiagnosed, and one has to have a clinical suspicion of it as an underlying disorder for many presenting complaints. Females are overrepresented, and the disease often appears in middle age (4-7 years), although any age or gender may be affected. Genetic continuity between dogs and humans helps to explain the occurrence of Addison's disease in both species.[12]

Hypoadrenocorticism is treated with prednisolone and/or fludrocortisone (Florinef (r)) or a monthly injection called Percorten V (desoxycorticosterone pivlate (DOCP)). Routine blood work is necessary periodically to assess therapy.

Most of the medications used in the therapy of hypoadrenocorticism cause excessive thirst and urination. It is absolutely vital to provide fresh drinking water for the canine sufferer.

If the owner knows about an upcoming stressful situation (shows, traveling etc.), patients generally need an increased dose of prednisone to help deal with the added stress. Avoidance of stress is important for dogs with hypoadrenocorticism.

[edit] Famous Addisonians

- United States President John F. Kennedy was one of the best-known Addison's disease sufferers. He was possibly one of the first Addisonians to survive major surgery.[13] There was substantial secrecy surrounding his health during his years as president, and the 25th amendment to the U.S. constitution was introduced at least in part as a result of this secrecy.[14]

- Popular singer Helen Reddy.[15]

- Scientist Eugene Merle Shoemaker, co-discoverer of the Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9.[16]

- French Carmelite nun and religious writer Blessed Elizabeth of the Trinity[17]

- Some have suggested that Jane Austen was an avant la lettre case, but others have disputed this.[18]

- According to Dr. Carl Abbott, a Canadian medical researcher, Charles Dickens may also have been affected.[19]

- Osama bin-Laden may be an Addisonian. Lawrence Wright noted that bin-Laden manifests all the key symptoms, such as "low blood pressure, weight loss, muscle fatigue, stomach irritability, sharp back pains, dehydration, and an abnormal craving for salt". Bin-Laden is known to have consumed large amounts of the drug Sulbutiamine to treat his symptoms.[20]

- Sabino Arana, Spanish writer and Basque nationalist[citation needed]

- Adrienne Herndon, Famous Black American educator and aspiring actress, married to Alonzo Hernadon, and mother of Norris Herndon.[citation needed]

- Turgut Cansever, the only Turkish architect to have received the Aga Khan Award for Architecture three times.

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ Addison disease at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Thomas Addison (HTML reprint). On The Constitutional And Local Effects Of Disease Of The Supra-Renal Capsules. London: Samuel Highley. http://www.wehner.org/addison/x1.htm.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ten S, New M, Maclaren N (2001). "Clinical review 130: Addison's disease 2001". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86 (7): 2909–22. doi:. PMID 11443143. http://jcem.endojournals.org/cgi/content/full/86/7/2909.

- ^ Patnaik MM, Deshpande AK (May 2008). "Diagnosis--Addison's disease secondary to tuberculosis of the adrenal glands". Clin Med Res 6 (1): 29. doi:. PMID 18591375. PMC: 2442022. http://www.clinmedres.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18591375.

- ^ James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 0721629210.

- ^ Addison's Disease National Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases Information Service. Retrieved on 26 October 2007.

- ^ Wang L, Yang J (2008). "Tuberculous Addison's disease mimics malignancy in FDG-PET images". Intern. Med. 47 (19): 1755–6. PMID 18827432. http://joi.jlc.jst.go.jp/JST.JSTAGE/internalmedicine/47.1348?from=PubMed.

- ^ "Addison Disease � Health information regarding this hormonal (endocrine) disorder on MedicineNet.com". http://www.medicinenet.com/addison_disease/article.htm. Retrieved on 2007-07-25.

- ^ a b "eMedicine - Addison Disease : Article by Sylvester Odeke". http://www.emedicine.com/med/topic42.htm. Retrieved on 2007-07-25.

- ^ "medhelp". http://www.medhelp.org/www/nadf3.htm. Retrieved on 2007-07-25.

- ^ Volpé, Robert (1990). Autoimmune Diseases of the Endocrine System. CRC Press. pp. 299. ISBN 0849368499.

- ^ "Dog Days Of Science". http://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/air/dog_days.htm. Retrieved on 2008-09-01.

- ^ Nicholas JA, Burstein CL, Umberger CJ, Wilson PD (November 1955). "Management of adrenocortical insufficiency during surgery". AMA Arch Surg 71 (5): 737–42. PMID 13268224.

- ^ Owen, David (May 2003). "Diseased, demented, depressed: serious illness in Heads of State". QJM: An International Journal of Medicine (Oxford University Press) 96 (5): 325–36. doi:. PMID 12702781. http://qjmed.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/96/5/325.

- ^ "The Australian Addison's Disease Association". http://www.addisons.org.au/core.htm?page=/awareness/awarenessweek.htm. Retrieved on 2007-07-25.

- ^ Marsden, Brian (1997-07-18). "Eugene Shoemaker (1928-1997)" (HTML). Comet Shoemaker-Levy Collision with Jupiter. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. http://www2.jpl.nasa.gov/sl9/news81.html. Retrieved on 2007-07-25.

- ^ Jones, Terry. "Patron Saints Index: Blessed Elizabeth of the Trinity". http://saints.sqpn.com/sainte46.htm. Retrieved on 2008-05-04.

- ^ Upfal, Annette (2005). "Jane Austen’s lifelong health problems and final illness: New evidence points to a fatal Hodgkin’s disease and excludes the widely accepted Addison's". Medical Humanities (BMJ Publishing Group Ltd) 31: 3–11. doi:. http://mh.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/31/1/3.

- ^ L. Williams et al. (1991). "The Nineteenth Century: Victorian Period". The Year's Work in English Studies (Oxford University Press) 72 (1): pp. 314–360. doi:. http://ywes.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/long/72/1/314.

- ^ Wright, Lawrence (2006). The Looming Tower. New York City: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. p. 139. ISBN 978-0375414862.

[edit] External links

- Overview of Addison's Disease from the Mayo Clinic

- Addison's Disease Research Today - monthly online journal summarizing recent primary literature on Addison's disease

- National Adrenal Diseases Foundation

- Addison's information from MedicineNet

- Addison's disease info from SeekWellness.com

- Information about Addison's disease in canines (dogs)

- Antibodies to adrenal gland

- Immunofluorescence images

- Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases Information Service

- Addison's Disease Self Help Group (UK)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||