Cosmology

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

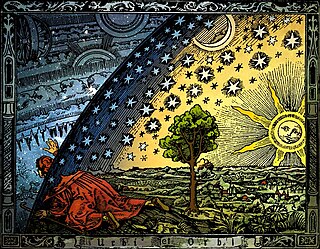

Cosmology (from Greek κοσμολογία - κόσμος, kosmos, "universe"; and -λογία, -logia, "study") is study of the Universe in its totality, and by extension, humanity's place in it. Though the word cosmology is recent (first used in 1730 in Christian Wolff's Cosmologia Generalis), study of the Universe has a long history involving science, philosophy, esotericism, and religion.

Contents |

[edit] Disciplines

| This article may contain original research or unverified claims. Please improve the article by adding references. See the talk page for details. (October 2008) |

In recent times, physics and astrophysics have to play a central role in shaping the understanding of the universe through scientific observation and experiment; or what is known as physical cosmology shaped through both mathematics and observation in the analysis of the whole universe. In other words, in this discipline, which focuses on the universe as it exists on the largest scale and at the earliest moments, is generally understood to begin with the big bang (possibly combined with cosmic inflation) - an expansion of space from which the Universe itself is thought to have emerged ~13.7±0.2×109 (13.7 billion) years ago[1] . From its violent beginnings and until its various speculative ends, cosmologists propose that the history of the Universe has been governed entirely by physical laws. Theories of an impersonal universe governed by physical laws were first proposed by Roger Bacon, a somewhat persecuted member of the Catholic Church.[2] Between the domains of religion and science, stands the philosophical perspective of metaphysical cosmology. This ancient field of study seeks to draw intuitive conclusions about the nature of the universe, man, god and/or their relationships based on the extension of some set of presumed facts borrowed from spiritual experience and/or observation.

But metaphysical cosmology has also been observed as the placing of man in the universe in relationship to all other entities. This is demonstrated by the observation made by Marcus Aurelius of a man's place in that relationship: " He who does not know what the world is does not know where he is, and he who does not know for what purpose the world exists, does not know who he is, nor what the world is.”[citation needed] This is the purpose of the ancient metaphysical cosmology. However, Stoicism rejected Aristotle's theory of universals as being "in the things themselves," calling them "figments of the mind." Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy adopting the concept of universals as being "concepts," and therefore of the mind, and therefore controllable by free will. Thus, we get the analysis of Aurelius' that the nature of the universe is not from "intuition," but from a free-will, conceptual understanding of the nature of the universe.[original research?]

Cosmology is often an important aspect of the creation myths of religions that seek to explain the existence and nature of reality. In some cases, views about the creation (cosmogony) and destruction (eschatology) of the universe play a central role in shaping a framework of religious cosmology for understanding humanity's role in the universe.

A more contemporary distinction between religion and philosophy, esoteric cosmology is distinguished from religion in its less tradition-bound construction and reliance on modern "intellectual understanding" rather than faith, and from philosophy in its emphasis on spirituality as a formative concept.

There are many historical cosmologies:

“…the universe itself acts on us as a random, inefficient, and yet in the long run effective, teaching machine. …our way of looking at the universe has gradually evolved through a natural selection of ideas.” —Steven Weinberg[3]

[edit] Historical cosmologies

The following table outlines the significant historical cosmologies in chronological order.

[edit] Historical descriptions of the cosmos

| Name | Author and date | Classification | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brahmanda | Hindu Rigveda (1500-1200 B.C.) | Cyclical or oscillating, Infinite in time | The universe is a cosmic egg that cycles between expansion and total collapse. It expanded from a concentrated form —a point called a Bindu. The universe, as a living entity, is bound to the perpetual cycle of birth, death, and rebirth |

| Atomist universe | Anaxagoras (500-428 B.C.) & later Epicurus | Infinite in extent | The universe contains only two things: an infinite number of tiny seeds, or atoms, and the void of infinite extent. All atoms are made of the same substance, but differ in size and shape. Objects are formed from atom aggregations and decay back into atoms. Incorporates Leucippus’ principle of causality: ”nothing happens at random; everything happens out of reason and necessity.” The universe was not ruled by gods. |

| Stoic universe | Stoics (400-200 B.C.) | Island universe | The cosmos is finite and surrounded by an infinite void. It is in a state of flux, as it pulsates in size and periodically passes through upheavals and conflagrations. |

| Aristotelian universe | Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) | Geocentric, static, steady state, finite extent, infinite time | Spherical earth is surrounded by concentric celestial spheres. Universe exists unchanged throughout eternity. Contains a 5th element called aether (later known as quintessence). |

| Aristarchean universe | Aristarchus (circa 280 B.C.) | Heliocentric | Earth rotates daily on its axis and revolves annually about the sun in a circular orbit. Sphere of fixed stars is centered about the sun. |

| Seleucian universe | Seleucus of Seleucia (circa 190 B.C.) | Heliocentric | Modifications to the Aristarchean universe, with the inclusion of the tide phenomenon to explain heliocentrism. |

| Ptolemaic model (based on Aristotelian universe) | Ptolemy (2nd century A.D.) | Geocentric | Universe orbits about a stationary Earth. Planets move in circular epicycles, each having a center that moved in a larger circular orbit (called an eccentric or a deferent) around a center-point near the Earth. The use of equants added another level of complexity and allowed astronomers to predict the positions of the planets. The most successful universe model of all time, using the criterion of longevity. Almagest (the Great System). |

| Aryabhatan model | Aryabhata (499 A.D.) | Geocentric or Heliocentric | The Earth rotates and the planets move in elliptical orbits, possibly around either the Earth or the Sun. It is uncertain whether the model is geocentric or heliocentric due to planetary orbits given with respect to both the Earth and the Sun. |

| Abrahamic universe | Medieval philosophers (500-1200) | Finite in time | The universe that is finite in time and has a beginning is proposed by the Christian philosopher, John Philoponus, who argues against the ancient Greek notion of an infinite past. Logical arguments supporting a finite universe are developed by the early Muslim philosopher, Alkindus; the Jewish philosopher, Saadia Gaon; and the Muslim theologian, Algazel. |

| Albumasar model | Ja'far ibn Muhammad Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi (787-886) | Heliocentric | His planetary orbits are only given with respect to the Sun rather than the Earth, thus suggesting a heliocentric model. |

| Maragha models | Maragha school (1259-1474) | Geocentric | Various modifications to the Ptolemaic model and Aristotelian universe, such as the rejection of the equant and eccentrics at the Maragheh observatory, the first accurate lunar model by Ibn al-Shatir, and the rejection of a stationery Earth in favour of the Earth's rotation by Ali Kuşçu. |

| Nilakanthan model | Nilakantha Somayaji (1444-1544) | Geocentric and Heliocentric | A universe in which the planets orbit the Sun and the Sun orbits the Earth, similar to the later Tychonic system. |

| Copernican universe | Nicolaus Copernicus (1543) | Heliocentric | The geocentric Maragha model of Ibn al-Shatir adapted to meet the requirements of the ancient heliocentric Aristarchean universe in his De revolutionibus orbium coelestium. |

| Tychonic system | Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) | Geocentric and Heliocentric | A universe in which the planets orbit the Sun and the Sun orbits the Earth, similar to the earlier Nilakanthan model. |

| Static Newtonian | Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) | Static (evolving), steady state, infinite | Every particle in the universe attracts every other particle. Matter on the large scale is uniformly distributed. Gravitationally balanced but unstable. |

| Cartesian Vortex universe | René Descartes

17th century |

Static (evolving), steady state, infinite | A system of huge swirling whirlpools of aethereal or fine matter produces what we would call gravitational effects. His vacuum was not empty. All space was filled with matter that swirled around in large and small vortices. |

| Hierarchical universe | Immanuel Kant, Johann Lambert 1700s | Static (evolving), steady state, infinite | Matter is clustered on ever larger scales of hierarchy. Matter is endlessly being recycled. |

| Einstein Universe with a cosmological constant | Albert Einstein 1917 | Static (nominally). Bounded (finite) | “Matter without motion.” Contains uniformly distributed matter. Uniformly curved spherical space; based on Riemann’s hypersphere. Curvature is set equal to Λ. In effect Λ is equivalent to a repulsive force which counteracts gravity. Unstable. |

| De Sitter universe | Willem de Sitter 1917 | Expanding flat space.

Steady state. Λ > 0 |

“Motion without matter.” Only apparently static. Based on Einstein’s General Relativity. Space expands with constant acceleration. Scale factor (radius of universe) increases exponentially, i.e. constant inflation. |

| MacMillan | William MacMillan 1920s | Static &

steady state |

New matter is created from radiation. Starlight is perpetually recycled into new matter particles. |

| Friedmann universe of spherical space | Alexander Friedmann 1922 | Spherical expanding space.

k= +1 ; no Λ |

Positive curvature. Curvature constant k = +1

Expands then recollapses. Spatially closed (finite). |

| Friedmann universe of hyperbolic space | Alexander Friedmann 1924 | Hyperbolic expanding space.

k= -1 ; no Λ |

Negative curvature. Said to be infinite (but ambiguous). Unbounded. Expands forever. |

| Dirac large numbers hypothesis | Paul Dirac 1930s | Expanding | Demands a large variation in G, which decreases with time. Gravity weakens as universe evolves. |

| Friedmann zero-curvature, aka the Einstein-DeSitter universe | Einstein & DeSitter 1932 | Expanding flat space.

k= 0 ; Λ = 0 Critical density |

Curvature constant k = 0. Said to be infinite (but ambiguous). ‘Unbounded cosmos of limited extent.’ Expands forever. ‘Simplest’ of all known universes. Named after but not considered by Friedmann. Has a deceleration term q =½ which means that its expansion rate slows down. |

| Georges Lemaître

the original Big Bang. aka Friedmann-Lemaître Model |

Georges Lemaître 1927-29 | Expansion

Λ > 0 Λ > |Gravity| |

Λ is positive and has a magnitude greater than Gravity. Universe has initial high density state (‘primeval atom’). Followed by a two stage expansion. Λ is used to destabilize the universe. (Lemaître is considered to be the father of the big bang model.) |

| Oscillating universe

(aka Friedmann-Einstein; was latter’s 1st choice after rejecting his own 1917 model) |

Favored by Friedmann

1920s |

Expanding and contracting in cycles | Time is endless and beginningless; thus avoids the beginning-of-time paradox. Perpetual cycles of big bang followed by big crunch. |

| Eddington | Arthur Eddington 1930 | first Static

then Expands |

Static Einstein 1917 universe with its instability disturbed into expansion mode; with relentless matter dilution becomes a DeSitter universe. Λ dominates gravity. |

| Milne universe of kinematic relativity | Edward Milne, 1933, 1935;

William H. McCrea, 1930s |

Kinematic expansion with NO space expansion | Rejects general relativity and the expanding space paradigm. Gravity not included as initial assumption. Obeys cosmological principle & rules of special relativity. The Milne expanding universe consists of a finite spherical cloud of particles (or galaxies) that expands WITHIN flat space which is infinite and otherwise empty. It has a center and a cosmic edge (the surface of the particle cloud) which expands at light speed. His explanation of gravity was elaborate and unconvincing. For instance, his universe has an infinite number of particles, hence infinite mass, within a finite cosmic volume. |

| Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker class of models | Howard Robertson, Arthur Walker, 1935 | Uniformly expanding | Class of universes that are homogenous and isotropic. Spacetime separates into uniformly curved space and cosmic time common to all comoving observers. The formulation system is now known as the FLRW or Robertson-Walker metrics of cosmic time and curved space. |

| Steady-state expanding (Bondi & Gold) | Herman Bondi, Thomas Gold 1948 | Expanding, steady state, infinite | Matter creation rate maintains constant density. Continuous creation out of nothing from nowhere. Exponential expansion. Deceleration term q = -1. |

| Steady-state expanding (Hoyle) | Fred Hoyle 1948 | Expanding, steady state; but unstable | Matter creation rate maintains constant density. But since matter creation rate must be exactly balanced with the space expansion rate the system is unstable. |

| Ambiplasma | Hannes Alfvén 1965 Oskar Klein | Cellular universe, expanding by means of matter-antimatter annihilation | Based on the concept of plasma cosmology. The universe is viewed as meta-galaxies divided by double layers —hence its bubble-like nature. Other universes are formed from other bubbles. Ongoing cosmic matter-antimatter annihilations keep the bubbles separated and moving apart preventing them from interacting. |

| Brans-Dicke | Carl H. Brans; Robert H. Dicke | Expanding | Based on Mach’s principle. G varies with time as universe expands. “But nobody is quite sure what Mach’s principle actually means.” |

| Cosmic inflation | Alan Guth 1980 | Big Bang with modification to solve horizon problem and flatness problem. | Based on the concept of hot inflation. The universe is viewed as a multiple quantum flux —hence its bubble-like nature. Other universes are formed from other bubbles. Ongoing cosmic expansion kept the bubbles separated and moving apart preventing them from interacting. |

| Eternal Inflation (a multiple universe model) | Andreï Linde 1983 | Big Bang with cosmic inflation | A multiverse, based on the concept of cold inflation, in which inflationary events occur at random each with independent initial conditions; some expand into bubble universes supposedly like our entire cosmos. Bubbles nucleate in a spacetime foam. |

| Cyclic model | Paul Steinhardt; Neil Turok 2002 | Expanding and contracting in cycles; M theory. | Two parallel orbifold planes or M-branes collide periodically in a higher dimensional space. With quintessence or dark energy |

Table Notes: the term “static” simply means not expanding and not contracting. Symbol G represents Newton’s gravitational constant; Λ (Lambda) is the cosmological constant.

[edit] Physical cosmology

Physical cosmology is the branch of physics and astrophysics that deals with the study of the physical origins and evolution of the Universe. It also includes the study of the nature of the Universe on its very largest scales. In its earliest form it was what is now known as celestial mechanics, the study of the heavens. The Greek philosophers Aristarchus of Samos, Aristotle and Ptolemy proposed different cosmological theories. In particular, the geocentric Ptolemaic system was the accepted theory to explain the motion of the heavens until Nicolaus Copernicus, and subsequently Johannes Kepler and Galileo Galilei proposed a heliocentric system in the 16th century. This is known as one of the most famous examples of epistemological rupture in physical cosmology.

Wit Isaac Newton and the 1687 publication of Principia Mathematica, the problem of the motion of the heavens was finally solved. Newton provided a physical mechanism for Kepler's laws and his law of universal gravitation allowed the anomalies in previous systems, caused by gravitational interaction between the planets, to be resolved. A fundamental difference between Newton's cosmology and those preceding it was the Copernican principle that the bodies on earth obey the same physical laws as all the celestial bodies. This was a crucial philosophical advance in physical cosmology.

Modern scientific cosmology is usually considered to have begun in 1917 with Albert Einstein's publication of his final modification of general relativity in the paper "Cosmological Considerations of the General Theory of Relativity," (although this paper was not widely available outside of Germany until the end of World War I). General relativity prompted cosmogonists such as Willem de Sitter, Karl Schwarzschild and Arthur Eddington to explore the astronomical consequences of the theory, which enhanced the growing ability of astronomers to study very distant objects. Prior to this (and for some time afterwards), physicists assumed that the Universe was static and unchanging. In parallel to this dynamic approach to cosmology, a debate was unfolding regarding the nature of the cosmos itself. On the one hand, Mount Wilson astronomer Harlow Shapley championed the model of a cosmos made up of the Milky Way star system only. Heber D. Curtis, on the other hand, suggested spiral nebulae were star systems in their own right, island universes. This difference of ideas came to a climax with the organization of the Great Debate at the meeting of the (US) National Academy of Sciences in Washington on 26 April 1920. The resolution of the debate on the structure of the cosmos came with the detection of novae in the Andromeda galaxy by Edwin Hubble in 1923 and 1924. Their distance established spiral nebulae well beyond the edge of the Milky Way and as galaxies of their own. Subsequent modeling of the universe explored the possibility that the cosmological constant introduced by Einstein in his 1917 paper may result in an expanding universe, depending on its value. Thus the big bang theory was proposed by the Belgian priest Georges Lemaître in 1927 which was subsequently corroborated by Edwin Hubble's discovery of the red shift in 1929 and later by the discovery of the cosmic microwave background radiation by Arno Penzias and Robert Woodrow Wilson in 1964. These findings were a first step to rule out some of many alternative physical cosmologies.

Recent observations made by the COBE and WMAP satellites observing this background radiation have effectively, in many scientists' eyes, transformed cosmology from a highly speculative science into a predictive science, as these observations matched predictions made by a theory called Cosmic inflation, which is a modification of the standard big bang theory. This has led many to refer to modern times as the "Golden age of cosmology".[4]

[edit] Metaphysical cosmology

In philosophy and metaphysics, cosmology deals with the world as the totality of space, time and all phenomena. Historically, it has had quite a broad scope, and in many cases was founded in religion. The ancient Greeks did not draw a distinction between this use and their model for the cosmos. However, in modern use it addresses questions about the Universe which are beyond the scope of science. It is distinguished from religious cosmology in that it approaches these questions using philosophical methods (e.g. dialectics). Modern metaphysical cosmology tries to address questions such as:

- What is the origin of the Universe? What is its first cause? Is its existence necessary? (see monism, pantheism, emanationism and creationism)

- What are the ultimate material components of the Universe? (see mechanism, dynamism, hylomorphism, atomism)

- What is the ultimate reason for the existence of the Universe? Does the cosmos have a purpose? (see teleology)

[edit] Religious cosmology

| This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. |

Many world religions have creation myths that explain the beginnings of the Universe and life. Often these are derived from scriptural teachings and held to be part of the faith's dogma, but in some cases these are also extended through the use of philosophical and metaphysical arguments.

In some creation myths, the universe was created by a direct act of a god or gods who are also responsible for the creation of humanity (see creationism). In many cases, religious cosmologies also foretell the end of the Universe, either through another divine act or as part of the original design.

- Both Christianity and Judaism rely on the Genesis narrative as a scriptural account of cosmology. See also Biblical cosmology and Tzimtzum.

- Islam relies on understanding from the Qur'an as its major source for explaining cosmology. See Islamic cosmology.

- Certain adherents of Buddhism, Hinduism (See also Hindu cosmology) and Jainism believe that the Universe passes through endless cycles of creation and destruction, each cycle lasting for trillions of years (e.g. 331 trillion years, or the life-span of Brahma, according to Hinduism), and each cycle with sub-cycles of local creation and destruction (e.g. 4.32 billion years, or a day of Brahma, according to Hinduism). The Vedic (Hindu) view of the world sees one true divine principle self-projecting as the divine word, 'birthing' the cosmos that we know from the monistic Hiranyagarbha or Golden Womb.

- A complex mixture of native Vedic gods, spirits, and demons, overlaid with imported Hindu and Buddhist deities, beliefs, and practices are the key to the Sri Lankan cosmology.

- The Australian Aboriginal concept of Dreaming explains the creation of the universe as an eternal continuum; everywhen. Through certain ceremonies, the past "opens up" and comes into the present. Each topographical feature is a manifestation of dormant creation spirits; each individual has personal Dreamings and ceremonial responsibilities to look after the spirits/land, determined at birth, within this belief framework.

Many religions accept the findings of physical cosmology, in particular the Big Bang, and some, such as the Roman Catholic Church, have embraced it as suggesting a philosophical first cause. Others have tried to use the methodology of science to advocate for their own religious cosmology, as in intelligent design or creationist cosmologies.

[edit] Esoteric cosmology

Many esoteric and occult teachings involve highly elaborate cosmologies. These constitute a "map" of the Universe and of states of existences and consciousness according to the worldview of that particular doctrine. Such cosmologies cover many of the same concerns also addressed by religious and philosophical cosmology, such as the origin, purpose, and destiny of the Universe and of consciousness and the nature of existence. For this reason it is difficult to distinguish where religion or philosophy end and esotericism and/or occultism begins.

Common themes addressed in esoteric cosmology are emanation, involution, evolution, epigenesis, planes of existence, hierarchies of spiritual beings, cosmic cycles (e.g., cosmic year, Yuga), yogic or spiritual disciplines, and references to altered states of consciousness. Examples of esoteric cosmologies can be found in modern Theosophy, Gnosticism, Tantra (especially Kashmir Shaivism), Kabbalah, or Sufism.

[edit] See also

[edit] Notes

- ^ "First Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations". http://arXiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0302209. Retrieved on 2003.

- ^ Roger Bacon. http://oce.catholic.com/index.php?title=Roger_Bacon.

- ^ Weinberg, Steven. 1992. Dreams of a Final Theory (Pantheon Books, NY) p158. ISBN 0-679-41923-3

- ^ Alan Guth is reported to have made this very claim in an Edge Foundation interview [1].

[edit] References

- Jean-Marc Rouvière, Brèves méditations sur la création du monde, L'Harmattan, Paris 2006.

- Roos, Matts Introduction to Cosmology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester: 2003.

- Hawley, John F. & Katerine A. Holcomb Foundations of Modern Cosmology. Oxford University Press, Oxford: 1998.

- Hetherington, Norriss S. Cosmology: Historical, Literary, Philosophical, Religious, and Scientific Perspectives. Garland Publishing, New York: 1993.

- Long, Barry. The Origins of Man and the Universe ISBN 0-9508050-6-8

- Martinus Thomsen's The Third Testament is about the explanation of life, everything inside it and the reason (or origin) of it.

- Arthur Koestler's The Sleepwalkers (1959) provides a scholarly study of the history of cosmology from the Chaldeans to Kepler.

- Gal-Or, Benjamin, Cosmology, Physics and Philosophy, Springer Verlag, 1981, 1983, 1987, New York

- Schechner, Sara J. Comets, Popular Culture, and the Birth of Modern Cosmology. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 1997.

[edit] External links

| Look up cosmology in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Cosmic Journey: A History of Scientific Cosmology from the American Institute of Physics

- Cosmology lecture notes with a GFDL license footer

- Vedic Cosmology

- The Quran and Cosmology