Foot binding

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2009) |

| This article includes a list of references or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please improve this article by introducing more precise citations where appropriate. (March 2009) |

Foot binding (simplified Chinese: 缠足; traditional Chinese: 纏足; pinyin: chánzú, literally "bound feet") was a custom practiced on young girls and women for approximately one thousand years in China, beginning in the 10th century and ending in the early 20th century.

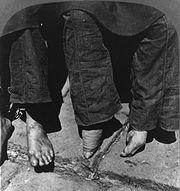

According to a study conducted by the University of California at San Francisco, "As the practice waned, some girls' feet were released after initial binding, leaving less severe deformities." Some effects of foot binding are permanent. In the 1990s and early 2000s, some elderly Chinese women still suffered from disabilities related to bound feet.[1]

The custom is commonly cited by sociologists and anthropologists as examples of how an extreme deformity by contemporary standards can be viewed as a source of beauty and pleasure, and how immense human suffering can be inflicted in the pursuit of female beauty.

Contents |

[edit] History

| This section includes a list of references or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please improve this article by introducing more precise citations where appropriate. (March 2009) |

Multiple accounts attempting to explain the origin of foot binding exist, each advancing a different theory: from the desire to emulate the naturally tiny feet of a favored concubine of a prince, to a story of an empress who had club-like feet, which became viewed as a desirable fashion. However, there is little strong textual evidence for the custom prior to the court of the Southern Tang dynasty in Nanjing, which celebrates the fame of its dancing girls renowned for their tiny feet and beautiful bow shoes. Foot binding was first present in the elite, and initially a common practice only in the wealthiest parts of China. However from the 17th century on the Han Chinese girls, from the wealthiest to the poorest peasants, had their feet bound. It is estimated more than four and one half billion Chinese women bound their feet from approximately 950 AD to 1949 when footbinding was outlawed by Mao. Manchu women were forbidden to bind their feet by an edict from the Emperor after the Manchu started their rule of China in 1644. The majority of the Minority People however followed the custom of binding the feet of their young girls. Some of the Minority People practiced loose binding which did not break the bones of the arch and toes, but narrowed the foot. The Hakka people, a unique ethnic group of Han descent, did not bind and had large natural feet. In the early twenty-first century, there have remained cases.

The main purpose of binding the feet was to break the arch of the foot which ultimately left a crevice approximately two inches deep in the foot which was considered most desireable. It took approximately two years for this process to reach the desired effect, hopefully a foot that measured three or three and one-half inches toe to heel. This perfect size was called the Golden Lotus. While footbinding could lead to serious infections, possible gangrene and were generally painful for life, contrary to many false tales the girls/women were able to walk, work in the fields, climb to mountain homes from valleys below. As late as 2005 women in one village in Yunnan Province formed an internationally known dancing troup to perform for foreign tourists. And in other areas women in their 70s and 80s could be found working in the rice fields well into the 21st century. In the 19th and early 20th century dancers with bound feet were very popular as were circus performers such as girls with bound feet standing on prancing or running horses.

There was a great pride in the tiny feet once the foot had developed into the lotus shape and this pride was shown in the slippers girls and women made to cover their deformed feet. Walking on these feet necessitated bending the knees slightly and swaying to maintain the proper movement. This swaying walk became known as the Lotus Gait and was considered most exciting to men. Manchu women who were forbidden to bind their feet, envious of the effect of the lotus gait, invented their own type of shoe that caused them also to walk with a swaying gait. They wore 'flower bowl' shoes, shoes on a high platform generally made of wood and also there was a shoe on a small central pedistal that could be maneuvered by young girls. These shoes enabled the wearer to walk with a form of the lotus gait. Bound feet became an important differentiating marker between Manchu and Han.

The practice continued into the 20th century, when a combination of Chinese and Western missionaries called for reform and a true anti-footbinding movement emerged. Educated Chinese began to realise that it made them appear barbaric to foreigners, social Darwinists argued that it weakened the nation, for enfeebled women inevitably produced weak sons (which matches the Lamarckism view on genetics), and feminists attacked it because it caused women to suffer.[2] At the turn of the 20th century, gentry women, such as Kwan Siew-Wah, a pioneer feminist, advocated for the end of female foot-binding. Kwan herself refused the foot-binding imposed on her since her youth so that she could grow normal feet.

Through the centuries there were unsuccessful attempts to stop the practice of footinding. Various emperors issued edicts to this effect but they were never successful. The Empress Dowager Cixi issued such an edict following the Boxer Rebellion to appease the foreigners, but it was rescinded a short time later. In 1911, after the fall of the Qing Dynasty, the new Republic of China government banned foot binding; women were told to unwrap their feet lest they be killed. Some women's feet grew 1/2 - 1 inch after the unwrapping, though some found the new growth process extremely painful and emotionally and culturally devastating. Societies developed to support the abolition of footbinding, with contractual agreements between families promising their infant son in marriage to an infant daughter that would not have her feet bound. When the Communists took power in 1949, they had the power to maintain the strict prohibition on footbinding, which is still in effect today.

In Taiwan, foot binding was banned by the Japanese administration in 1915.

[edit] Reception and appeal

Bound feet were considered intensely erotic. Qing Dynasty sex manuals listed 46 different ways of playing with women's bound feet. [1] Some men preferred never to see a woman's bound feet, so they were always concealed within tiny "lotus shoes". Feng Xun is recorded as stating, "If you remove the shoes and bindings, the aesthetic feeling will be destroyed forever." For them, the erotic effect was a function of the lotus gait, the tiny steps and swaying walk of a woman whose feet had been bound. The very fact that the bound foot was concealed from men's eyes was, in and of itself, sexually appealing. On the other hand, an uncovered foot would also give off a foul odor, as various fungi would colonise the unwashable folds. The other primary attribute of a woman having bound feet was to limit her mobility, altering the means by which females were allowed to be a part of politics and of the world at large. It also gave the woman an irreversible dependency on her family. Thus bound feet became an alluring symbol of chastity, as a bound foot woman was largely restricted to her home and could not venture far without an escort to help her, thus denying any advances upon her and ensuring her total and absolute devotion to her husband

[edit] Process

At about the age of six or seven when the bones of the young girl's feet were fully developed the footbinding began. It was generally an elder female member of the girl's family or a professional footbinder who started the binding. It was seen as preferable to avoid having the mother do it as she might be sympathetic to the pain of her daughter's feet and loosen the bandages. The process was started before the arch of the foot had a chance to properly develop. Binding usually started during the winter months so that the feet were numb, meaning the pain would not be as extreme.[3]

First, each foot would be soaked in a warm mixture of herbs and animal blood, this is to soften the foot to aid the binding. Then her toenails were cut back as far as possible to prevent ingrowth and subsequent infections since the toes were to be pressed tightly into the sole of the foot. To prepare her for what was to come next the girl's feet were delicately massaged. Cotton bandages, ten feet long and two inches wide, were prepared by soaking them in the same blood and herb mix as before. The toes on each foot were pressed downwards into the sole of the foot until they were broken, and held against the sole of the foot. The foot was then drawn straight with the leg and the arch broken. The bandage would be repeatedly wound in a figure eight movement, starting at the inside of the foot at the instep, then carried over the toes, under the foot, and round the heel, the freshly broken toes being pressed tightly into the sole of the foot. At each pass the binding was tightened, pulling the ball of the foot and the heel ever close together. When the binding is done, the end of the binding cloth is sewn tightly to prevent the girl from loosening it. As the wet bandages dried they would constrict greatly, making the binding even tighter.

This binding ritual would be repeated as often as possible (for the rich at least once daily, for poor peasants two or three times a week), with fresh bindings. Each time the feet were unbound they would be kneaded to make the joints more flexible, then washed and the nails meticulously trimmed. Immediately after this pedicure the feet are rebound and the bindings are pulled tighter each time, making this process continually more and more painful. The unbound feet would regularly be soaked in a concoction (also considered a "special potion") that caused any necrotised flesh to fall off.[4] The girl was not allowed to rest after her feet had been bound, however much pain she was in she would often have to walk long distances on her broken & bound feet, so that her own body weight crushed her feet into the correct shape. The most common ailment of bound feet was infection. Toenails would often ingrow and could lead to flesh rotting, if the infection got into the bones of the feet it could cause toes to drop off. Toes dropping off was seen as a positive, as the feet could then be bound even tighter than before. Disease inevitably followed infection meaning that death could result from foot binding. As the girl grew older, she was more at risk from medical problems. Even after the foot bones healed they were prone to re-breaking. Older women were more likely to break hips and other bones in falls and were less able to stand up from sitting.[5]

[edit] Foot binding in literature and film

Anchee Min describes a graphic depiction of a young girl's foot binding in her memoir Red Azalea, as well as another's refusal to have her feet bound in Becoming Madame Mao.

Lisa See has read widely and writes about foot binding in Snow Flower and the Secret Fan and Peony in Love.

Li Juzhen (1763-1830) wrote a satirical novel Jinghua yuan, translated as Flowers in the Mirror which includes a visit to the mythical Kingdom of Women. There it is the men who must bear children, menstruate, and bind their feet. The recent Chinese author Feng Jicai's (b. 1942) novel Three Inch Golden Lotus presents a satirical picture of the movement to abolish the practice.

In Lensey Namioka's Ties That Bind, Ties That Break, 5-year-old Ailin refuses to have her feet bound, causing the family of her intended husband to break their marriage agreement.

In the novel and miniseries Broken Trail, by Alan Geoffrion, one of the young Chinese slaves has bound feet and relies heavily on others for support while walking.

Isabelle Allende's novel Daughter of Fortune includes a character whose feet have been bound, as well as a several passages about the aesthetics of foot-binding.

Diana Gabaldon's novel Voyager (the fourth installment of the Outlander series) includes a Chinese character who explains his foot binding and the sexual aspect of it.

Ji-li Jiang wrote the book Red Scarf Girl and in it Ji li's grandmother had incredibly tiny feet (smaller than three inches) due to her binding her feet as a young child.

James Clavell's novel Tai-Pan describes a bride with bound feet and the custom of binding the feet.

Kathryn Harrison's novel The Binding Chair describes the process of foot-binding, as well as exploring some of the trauma associated with the practice.

Donna Jo Napoli's novel Bound describes the painful foot-binding of the main character's sister, much past the usual age for the practice of foot-binding.

In the Filipino horror film Feng Shui, which tells about an old bagua mirror that showers luck and prosperity to its owner and brings death to those near her, the malevolent spirit behind the curse was called Lotus Feet. It was revealed that the youngest female member among the siblings of a rich Chinese family died in a fire in Shanghai, during the Chinese Civil War, while she was left behind by fleeing Nationalist family members and unable to escape due to her walking handicap. The arson was perpetuated by rebelling servants who joined the communists. Her dead body was found holding the bagua mirror, and her vengeful spirit that was bound to it brought the deadly curse.

[edit] See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Foot binding |

- Attraction to disability

- Artificial cranial deformation

- Body modification

- Corset

- Sexual fetishism

- Foot fetishism

- Female genital cutting

- Violence against women

[edit] Notes

- ^ a b Painful Memories for China's Footbinding Survivors, by Louisa Lim, Morning Edition, March 19, 2007. Accessed March 19, 2007.

- ^ Levy (1992), p. 322

- ^ Jackson, Beverly: Splendid Slippers. Berkley: Tenspeed Press. 1997

- ^ Levy, Howard S: The Lotus Lovers: The Complete History of the Curious Erotic Tradition of Foot Binding in China. New York:Prometheus Books 1991

- ^ Cummings, S & Stone, K: Consequences of Foot Binding Among Older Women in Beijing China. American Journal of Public Health EBSCO Host. Oct 1997

[edit] References

- Dorothy Ko, Cinderella’s Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2005.

- Dorothy Ko, Every Step a Lotus: Shoes for Bound Feet (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001). Catalogue of a museum exhibit, with extensive comments.

- Beverley Jackson Splendid Slippers - A Thousand Years of an Erotic Tradition: Ten Speed Press

- Howard S. Levy, The Lotus Lovers: Prometheus Books, New York, 1992

- Eugene E.Berg, , M.D. Chinese Footbinding. Radiology Review - Orthopaedic Nursing 24, no. 5 (September/October) 66-67

- Marie Vento, [1]One Thousand Years of Chinese Footbinding: Its Origins, Popularity and Demise

- The Virtual Museum of The City of San Francisco, [2]

- Ping, Wang. Aching for Beauty: Footbinding in China. New York: Anchor Books, 2002.

[edit] Fictional accounts

- Li Ju-chen [Li Ruzhen], Flowers in the Mirror translated, edited by Lin Tai-yi (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1965).

- Lisa See, Snow Flower and the Secret Fan: A novel (New York: Random House, 2005)

- Jicai Feng (translated from the Chinese by David Wakefield), The Three-Inch Golden Lotus (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1994).

- Kathryn Harrison, The Binding Chair, or, a Visit from the Foot Emancipation Society: A Novel (New York: Random House, 2000).

[edit] Further reading

- Fan Hong, Footbinding, Feminism and Freedom (Frank Cass, London, 1997)

- Peter M Austin, Foot Binding - Lotus Feet are not just spun Mysoginist Femanism (Peter M Austin, London, 2008)

[edit] External links

- "Chinese Girl with Bound Feet" Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco.

- Page about Chinese foot binding

- Page from thinkquest

- Another page on foot binding

- A photograph

- A page on foot binding