Wheel of the Year

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

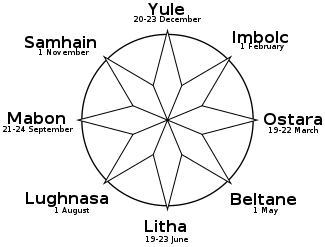

The Wheel of the Year is a Wiccan and Neopagan term for the annual cycle of the Earth's seasons. It consists of eight festivals, spaced at approximately even intervals throughout the year. These festivals are referred to by Wiccans as Sabbats. These festivals have historical origins in Celtic and Germanic pre-Christian feasts, and the Wheel of the Year, as has developed in modern Neopaganism and Modern Wicca, is really a combination of the two cultures solstice and equinox celebrations. When melded together, two somewhat unrelated European Festival Cycles merge to form eight festivals in modern renderings. Together, these festivals are understood by some to be the Bronze Age religious festivals of Europe. As with all cultures' use of festivals and traditions, these festivals have been utilized by European cultures in both the pre and post Christian eras as traditional times for the community to celebrate the planting and harvest seasons. The Wheel of the Year has been important to many people both ancient and modern, from various religious as well as cultural and secular viewpoints.

In many forms of Neopaganism, natural processes are seen as following a continuous cycle. The passing of time is also seen as cyclical, and is represented by a circle or wheel. The progression of birth, life, decline and death, as experienced in human lives, is echoed in the progression of the seasons. Wiccans also see this cycle as echoing the life, death and rebirth of their Horned God and the fertility of their Goddess.

While most of these names derive from historical Celtic and Germanic festivals, the non-traditional names Litha and Mabon, which have become popular in North American Wicca, were introduced by Aidan Kelly in the 1970s. The word "sabbat" itself comes from the witches' sabbath or sabbat attested to in Early Modern witch trials

Contents |

[edit] Eight festivals

Wiccans, and some other Neopagan groups, observe eight festivals which they call "sabbats".[1] Four of these fall on the solstices and equinoxes and are known as "quarter days" or "Lesser Sabbats". The other four fall (approximately) midway between these and are commonly known as "cross-quarter days," "fire festivals," or "Greater Sabbats". The "quarter days" are loosely based on or named after the Germanic festivals, and the "cross-quarter days" are similarly inspired by the Gaelic fire festivals. However, modern interpretations vary widely, so Pagan groups may celebrate and conceptualize these festivals in very different ways, often having little in common with the cultural festivals outside of the adopted name.[2]

The full system of eight yearly festivals held on these dates is unknown in older pagan calendars, and originated in the modern Wiccan religion.[3]

The eight major festivals (or "sabbats") are distinct from the Wiccan "esbats", which are additional meetings, usually smaller celebrations or coven meetings, held on full or new moons.

| Festival name | NH Date | SH Date | Sun's Position (NH) | Sun's Position (SH) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samhain, Halloween, Last/Blood Harvest, Ancestor Night, Feast of the Dead, Noson Calan Gaeaf | 31 Oct-2 Nov (alt. 5-10 Nov) | 1 May (alt. 4-10 May) | ≈ 15° Scorpio | ≈ 15° Taurus |

| Midwinter, Yule, Cuidle, Alban Arthan, Winter Rite, Mothers Night | 19-23 Dec (winter solstice) | 19-23 June (winter solstice) | 0° Capricorn | 0° Cancer |

| Candlemas, Imbolc, Oimelc, Brigit, Brigid's Day, Bride's Day, Brigantia | 1-2 Feb (alt. 2-7 Feb) | 1-2 Aug (alt. 3-10 Aug) | ≈ 15° Aquarius | ≈ 15° Leo |

| Vernal Equinox, Ostara, Lady Day, Earrach, Alban Eilir, Festival of Trees | 20-23 Mar (spring equinox) | 19-23 Sept (spring equinox) | 0° Aries | 0° Libra |

| Beltane, Beltaine, May Day | 1 May (alt. 4-10 May) | 31 Oct-2 Nov (alt. 5-10 Nov) | ≈ 15° Taurus | ≈ 15° Scorpio |

| Midsummer, Litha, Samradh, Alban Hefin, Aerra Litha | 19-23 June (summer solstice) | 19-23 Dec (summer solstice) | 0° Cancer | 0° Capricorn |

| Lammas, Lughnasadh (/luːnəsə/), 1st Harvest, Bread Harvest, Festival of First Fruits | 1-2 Aug (alt. 3-10 Aug) | 1-2 Feb (alt. 2-7 Feb) | ≈ 15° Leo | ≈ 15° Aquarius |

| Autumnal Equinox, Mabon, Foghar, Alban Elfed, Harvest Home, 2nd Harvest, Fruit Harvest, Wine Harvest | 19-23 Sept (autumn equinox) | 20-23 Mar (autumn equinox) | 0° Libra | 0° Aries |

[edit] Samhain

Samhain is considered by most Wiccans to be the most important of the four 'greater Sabbats'. It is generally observed on October 31st in the Northern Hemisphere, starting at sundown. Samhain is considered by some Wiccans as a time to celebrate the lives of those who have passed on, and it often involves paying respect to ancestors, family members, elders of the faith, friends, pets and other loved ones who have died. In some rituals the spirits of the departed are invited to attend the festivities. It is seen as a festival of darkness, which is balanced at the opposite point of the wheel by the spring festival of Beltane, which Wiccans celebrate as a festival of light and fertility.[4]

The Wiccan Samhain doesn't attempt to reconstruct a historical Celtic festival, but draws inspiration from both extinct and surviving Halloween folk traditions.[5]

[edit] Midwinter

In most Wiccan traditions, Yule is celebrated as the rebirth of the Great God,[6] who is viewed as the newborn solstice sun. The method of gathering for this sabbat varies by group or individual practitioner. Some have private ceremonies at home,[7] while others hold coven celebrations.[8]

[edit] Candlemas

Wiccans celebrate Candlemas or Imbolc as one of four "fire festivals" of the Wheel of the Year. Among Dianic Wiccans, Imbolc is the traditional time for initiations.[9]

Among Reclaiming-style Wiccans, Imbolc is considered a traditional time for rededication and pledges for the coming year.[4]

[edit] Vernal Equinox

The vernal equinox, sometimes called Ostara, is celebrated in the Northern hemisphere around March 21 and in the Southern hemisphere around September 23, depending upon the specific timing of the equinox. Among the Wiccan sabbats, it is preceded by Candlemas and followed by Beltane.

The name Ostara is from ôstarâ, the Old High German for "Easter". It has been connected to the putative Anglo-Saxon goddess Eostre by Jacob Grimm in his Deutsche Mythologie.[10].

In terms of Wiccan ditheism, this festival is characterized by the rejoining of the Mother Goddess and her lover-consort-son, who spent the winter months in death.[11] Other variations include the young God regaining strength in his youth after being born at Yule, and the Goddess returning to her Maiden aspect.

[edit] Beltane

Beltane is one of the four "fire festivals" or "greater sabbats". Although the holiday may use features of the Gaelic Bealtaine, such as the bonfire, it bears more relation to the Germanic May Day festival, both in its significance (focusing on fertility) and its rituals (such as maypole dancing). Some Wiccans celebrate 'High Beltaine' by enacting a ritual union of the May Lord and Lady.[4]

[edit] Midsummer

Midsummer is one of the four solar holidays, and is considered the turning point at which summer reaches its height and the sun shines longest. Among the Wiccan sabbats, Midsummer is preceded by Beltane, and followed by Lammas or Lughnasadh.

Some traditions call the festival "Litha", a name occurring in Bede's "Reckoning of Time" (De Temporum Ratione, 7th century), which preserves a list of the (then-obsolete) Anglo-Saxon names for the twelve months. Ærra Liða ('first' or 'preceding' Liða) roughly corresponds to June in our calendar, and Æfterra Liða ('following' Liða) to July. Bede writes that "Litha means 'gentle' or 'navigable', because in both these months the calm breezes are gentle and they were wont to sail upon the smooth sea."[12]

[edit] Lammas

Lammas or Lughnasadh is the first of the three autumn harvest festivals, the other two being the Autumn equinox (or Mabon) and Samhain. Some Wiccans mark the holiday by baking a figure of the god in bread, and then symbolically sacrificing and eating it. These celebrations are not based on Celtic culture, despite common use of a Celtic name Lughnasadh.[4][5] This name seems to have been a late adoption among Wiccans, since in early versions of Wiccan literature the festival is merely referred to as "August Eve".[13]

The name Lammas implies it is an agrarian-based festival and feast of thanksgiving for grain and bread, which symbolizes the first fruits of the harvest. Wiccan and other eclectic Neopagan rituals may incorporate elements from either festival.[4]

[edit] Autumnal Equinox

The holiday of Autumn Equinox, Harvest Home, Mabon, the Feast of the Ingathering, Meán Fómhair or Alban Elfed (in Neo-Druidic traditions), is a ritual of thanksgiving for the fruits of the earth and a recognition of the need to share them to secure the blessings of the Goddess and God during the winter months. The name Mabon was coined by Aidan Kelly around 1970 as a reference to Mabon ap Modron, a character from Welsh mythology.[14] In the northern hemisphere this equinox occurs anywhere from September 21 to 24. In the southern hemisphere, the autumn equinox occurs anywhere from March 19 to 22. Among the sabbats, it is the second of the three harvest festivals, preceded by Lammas/Lughnasadh and followed by Samhain.

[edit] Dates

Dates for the festivals vary widely. There are many forms of Wicca and Neopaganism, all of which may have somewhat different traditions associated with the festivals. Therefore there is no definitive or universal tradition observed by all the groups. Most Pagans are somewhat flexible about dates, tending to celebrate at the nearest weekend for convenience.

[edit] Hemispheres

As the Wheel originates in the Northern Hemisphere, in the Southern Hemisphere many Neopagans advance these dates six months so as to coincide with the natural seasons as they occur in their local climates. For instance, a Wiccan from southern Australia may celebrate Beltane on the 1st of November, when a Canadian Wiccan is celebrating Samhain. The appropriate set of festivals for an Equatorial Wiccan is problematic.

[edit] Quarter Days

While the cross-quarter days traditionally fall on the Kalends of the month, some Neopagans consider them to fall on the midpoint of the two surrounding quarter days. These modern calculations tend to result in celebrations held a few days after the traditional dates (see above table).

[edit] Sun Sabbats and Moon Sabbats

"Sun sabbats" refer to the quarter days, which are based on the astronomical position of the sun. The remaining four, Candlemas, Beltane, Lammas and Samhain are sometimes called "moon sabbats", and observed on Full Moons or - especially Samhain - on a Dark Moon. Typically the Full Moon closest to the traditional festival date or the 2nd full moon after the preceding sun sabbat is chosen. This would place the moon sabbat anywhere from 29-59 days after the preceding solstice or equinox.

[edit] Origins

Most of the holidays of the Wheel of the Year are named after Christian, Pre-Christian Celtic and Pre-Christian Germanic religious festivals, but depart largely in form and meaning from the traditional observances of those festivals. Historian Ronald Hutton ascribes this to the influence of turn of the century romanticism as well as the eclectic elements introduced by Wicca. The similarities between these holidays generally end at the shared names, as Wicca makes no effort to reconstruct the ancient practices.[5] Hutton has described the merging of culturally diverse festivals into a unified set of eight as a form of universalism not corroborated by any historical continuity.[5]

There is no place in Europe where all eight festivals have been observed as a set, and the complete eightfold Wheel of the Year was unknown prior to modern Wicca.[5] In early forms of Wicca only the cross-quarter days were observed. However, in 1958 the members of Bricket Wood Coven added the solstices and equinoxes to their original calendar, as they desired more frequent celebrations. Their High Priest, Gerald Gardner, was away visiting the Isle of Man at the time, but he did not object when he returned, since they were now more in line with the Neo-druidism of Ross Nichols, a friend of Gardner's and founder of the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids.[15]

| “ | No known pre-Christian people celebrated all the eight festivals of the calendar adopted by Wicca. Around the four genuine Gaelic quarter days are now ranged the Midwinter and September feasts of the Anglo-Saxons, the Midsummer celebrations so prominent in folklore and (for symmetry) the vernal equinox, which does not seem to have been commemorated by any ancient northern Europeans.[5] | ” |

[edit] Narratives

Among Wiccans, the most common Wheel of the Year narrative is that of the God/Goddess duality. In this cycle, the God is born from the Goddess at Yule, grows in power at Vernal Equinox (along with the Goddess who has now returned to her maiden aspect), courts and impregnates the Goddess at Beltane, wanes in power at Lammas, passes into the underworld at Samhain, then is once again born from Her mother/crone aspect at Yule. The Goddess, in turn, ages and rejuvenates endlessly with the seasons, being courted by and giving birth to the Horned God. Versions of this myth vary from coven to coven, shifting the birth, conception, or death of the God to different sabbats.

Another, more solar, narrative is of the Holly King and the Oak King, with one ruling the winter, the other the summer. These two figures battle with each other endlessly as the seasons turn. At Midsummer the Oak King is at the height of his strength, while the Holly King is at his weakest. The Holly King begins to regain his power, and at the Autumn Equinox, the tables finally turn in the Holly King's favor; he vanquishes the Oak King at Yule. Then over the next months, as the sun waxes in power, the Oak King slowly regains his strength; at the Spring Equinox he begins to triumph until he once again defeats the Holly King at Midsummer.[16]

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ http://www.hamiltonspectator.com/NASApp/cs/ContentServer?pagename=hamilton/Layout/Article_Type1&c=Article&cid=1172877012955&call_pageid=1020420665036&col=1112188062620 Wiccan Veterans waging new war Devon Haynie March 3, 2007

- ^ http://wicca.timerift.net/sabbat.shtml "The Wheel of the Year/the Sabbats"

- ^ http://www.manygods.org.uk/articles/essays/wheel.html "The Eightfold Wheel of the Year" Moonhunter 2003

- ^ a b c d e Starhawk (1979, 1989) The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess. New York, Harper and Row ISBN 0-06-250814-8 pp.193-6 (revised edition)

- ^ a b c d e f Hutton, Ronald. The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles. Oxford, Blackwell. pp. 337–341. ISBN 0-631-18946-7.

- ^ James Buescher (2007-12-15). "Wiccans, pagans ready to celebrate Yule". Lancaster Online. http://local.lancasteronline.com/4/213802. Retrieved on 2007-12-21.

- ^ Andrea Kannapell (1997-12-21). "Celebrations; It's Solstice, Hanukkah, Kwannza: Let There Be Light!". nytimes.com. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9507E5DA113FF932A15751C1A961958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all. Retrieved on 2007-12-21.

- ^ Ruth la Ferla (2000-12-13). "Like Magic, Witchcraft Charms Teenagers". nytimes.com. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9A04E3DD1E3EF930A25751C0A9669C8B63&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=1. Retrieved on 2007-12-21.

- ^ Budapest, Zsuzsanna (1980) The Holy Book of Women's Mysteries ISBN 0-914728-67-9

- ^ Grimm, Jacob (1835). Deutsche Mythologie (German Mythology); From English released version Grimm's Teutonic Mythology (1888); Available online by Northvegr © 2004-2007, Chapter 13, page 10+

- ^ Eight Sabbats for Witches by Janet and Stewart Farrar

- ^ Bede & Wallis, Faith (tr.) (1999) Bede, The Reckoning of Time Liverpool University Press. p. 54.

- ^ The Gardnerian Book of Shadows online

- ^ Oberon Zell-Ravenheart & Morning Glory Zell-Ravenheart (2006) Creating Circles & Ceremonies: Rituals for All Seasons and Reasons. Career Press. p. 227.

- ^ Lamond, Frederic (2004). Fifty Years of Wicca. Sutton Mallet, England: Green Magic. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0-9547230-1-5.

- ^ Farrar, Janet and Stewart (1988). Eight Sabbats for Witches, revised edition. Phoenix Publishing. ISBN 0-919345-26-3.

[edit] External links

- Seasons (astronomically) by Archaeoastronomy

- About the Sabbats by Judy Harrow of the Proteus coven.

- The Eightfold Wheel by Moonhunter, from the Association of Polytheist Traditions website.