Bible code

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Hidden messages |

|---|

| Audio |

| Numeric |

|

| Visual |

| See also: |

The Bible code, also known as the Torah code, is a cipher alleged to exist within the texts, that when decoded form words and phrases supposedly demonstrating foreknowledge and prophecy. The study and results from this cipher have been popularized by the book The Bible Code.

Contents |

[edit] Overview

Contemporary discussion and controversy around one specific encryption method became widespread in 1994 when Doron Witztum, Eliyahu Rips and Yoav Rosenberg published a paper, "Equidistant Letter Sequences in the Book of Genesis" in the scientific journal Statistical Science[1]. The paper, which was presented by the journal as a "challenging puzzle", claimed to present strong statistical evidence that biographical information about famous rabbis was encoded in the text of the Bible, centuries before those rabbis lived.

Since then the term "Bible Codes" has been popularly used to refer specifically to information encrypted via the ELS method.

Since the Witztum, Rips and Rosenberg (WRR) paper was published, two conflicting schools of thought regarding the "Codes" have emerged among proponents. The traditional (WRR) view of the codes is based strictly on their applicability to the Torah, and asserts that any attempt to study the codes outside of this context is invalid. This is based on a belief that the Torah is unique among biblical texts in that it was given directly to mankind (via Moses) in exact letter-by-letter sequence and in the original Hebrew language.

[edit] ELS - Equidistant Letter Sequence method

The primary method by which purportedly meaningful messages have been extracted is the Equidistant Letter Sequence (ELS). To obtain an ELS from a text, choose a starting point (in principle, any letter) and a skip number, also freely and possibly negative. Then, beginning at the starting point, select letters from the text at equal spacing as given by the skip number. For example, the bold letters in this sentence form an ELS. With a skip of -4, and ignoring the spaces and punctuation, the word SAFEST is spelled out backwards.

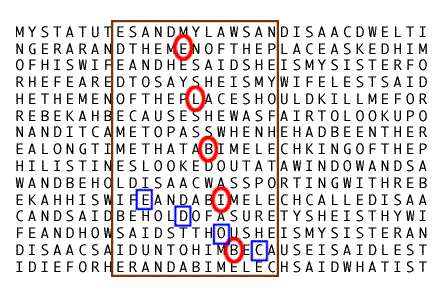

Often more than one ELS related to some topic can be displayed simultaneously in an ELS letter array. This is produced by writing out the text in a regular grid, with exactly the same number of letters in each line, then cutting out a rectangle. In the example below, part of the King James Version of Genesis (26:5–10) is shown with 33 letters per line. ELSs for BIBLE and CODE are shown. Normally only a smaller rectangle would be displayed, such as the rectangle drawn in the figure. In that case there would be letters missing between adjacent lines in the picture, but it is essential that the number of missing letters be the same for each pair of adjacent lines.

Although the above examples are in English texts, Bible codes proponents usually use a Hebrew Bible text. For religious reasons, most Jewish proponents use only the Torah (Genesis–Deuteronomy).

[edit] ELS extensions

Once a specific word has been found as an ELS, it is natural to see if that word is part of a longer ELS consisting of multiple words.[2] For example, in the middle of the rightmost column of the boxed matrix above is the ELS "he". After searching immediately above and below this ELS, we see another ELS ("toe") that is right below the "he" ELS. Code pioneers Haralick and Rips have published an example of a longer, extended ELS, which reads, "Destruction I will call you; cursed is Bin Laden and vengeance from the Moshiach." [3]

ELS extensions that form phrases or sentences are of interest. Bible code proponents claim that the longer the extended ELS, the less likely it is to be the result of chance.[4]

[edit] History

An early seeker of divinely encrypted messages was Isaac Newton, who, according to John Maynard Keynes, believed[5] that "the universe is a cryptogram set by the Almighty", and in the structure of the universe, Newton sought the answers to "a riddle of the Godhead of past and future events divinely fore-ordained".

The 13th-century Spanish Rabbi Bachya ben Asher may have been the first[citation needed] to describe an ELS in the Bible. His 4-letter example related to the traditional zero-point of the Hebrew calendar. Over the following centuries there are some hints that the ELS technique was known, but few definite examples have been found from before the middle of the 20th century. At this point many examples were found by the Slovak Rabbi Michael Ber Weissmandl and published by his students after his death in 1957. Nevertheless, the practice remained known only to a few until the early 1980s, when some discoveries of an Israeli school teacher Avraham Oren came to the attention of the mathematician Eliyahu Rips at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Rips then took up the study together with his religious studies partners Doron Witztum and Alexander Rotenberg, and several others.

Rips and Witztum designed computer software for the ELS technique and subsequently found many examples. About 1985, they decided to carry out a formal test, and the "Great rabbis experiment" was born. This experiment tested the hypothesis that ELSs for the names of famous rabbis could be found closer to ELSs of their dates of birth and death than chance alone could explain. The definition of "close" was complex but, roughly, two ELSs are close if they can be displayed together in a small rectangle. The experiment succeeded in finding sequences which fit these definitions, and they were interpreted as indicating the phenomenon was real.

The "great rabbis experiment" went through several iterations, and was eventually published in 1994, in the peer-reviewed journal Statistical Science. Prior to publication, the journal's editor, Robert Kass, subjected the paper to three successive peer reviews by the journal's referees, who according to Kass were "baffled". Though still skeptical,[6] none of the reviewers had found any flaws. Understanding that the paper was certain to generate controversy, it was presented to readers in the context of a "challenging puzzle".

Witztum and Rips also performed other experiments, most of them successful, though none were published in journals. Another experiment, in which the names of the famous rabbis were matched against the places of their births and deaths (rather than the dates), was conducted by Harold Gans, Senior Cryptologic Mathematician for the United States National Security Agency.[7] Again, the results were interpreted as being meaningful and thus suggestive of a more than chance result. These Bible codes became known to the public primarily due to the American journalist Michael Drosnin, whose book The Bible Code (Simon and Schuster, 1997) was a best-seller in many countries. Rips issued a public statement that he did not support Drosnin's work or conclusions.[8]

In 2002, Drosnin published a second book on the same subject, called The Bible Code II. The Jewish outreach group Aish-HaTorah employs the Bible Codes in their Discovery Seminars to persuade secular Jews of the divinity of the Bible, and to encourage them to trust in its traditional Orthodox teachings. Use of Bible code techniques also spread into certain Christian circles, especially in the United States. The main early proponents were Yakov Rambsel, who is a Messianic Jew, and Grant Jeffrey. Another Bible code technique was developed in 1997 by Dean Coombs (also Christian). Various pictograms are claimed to be formed by words and sentences using ELS.[9]

Since 2000, physicist Nathan Jacobi, an agnostic Jew, and engineer Moshe Aharon Shak, an orthodox Jew, have discovered hundreds of examples of lengthy, extended ELSs. [10] The number of extended ELSs at different lengths is compared with those expected from a non-encoded text, as determined by a formula from Markov Chain Theory.[11]

[edit] Recent developments

Yitzchok Adlerstein, self-described as "one of the most vocal skeptics" of the Bible Codes, noted that on October 10, 2005, the Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to leading Bible Code proponent Robert Aumann for his work in game theory, the same field that led to an earlier award to John Nash. Reviewing Aumann's 2004 concluding remarks in response to the "Gans Committee" study[12] in the context of Aumann's twenty years of codes research, Adlerstein noted that Aumann had come to the conclusion that the codes could neither be proven nor could they be disproven with the scientific methods employed to date.[13]

In 2006, three new Torah Codes papers were published at the 18th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR'06). Nachum Bombach and Harold Gans presented "Patterns of Co-Linear Equidistant Letter Sequences and Verses", WRR author Eliyahu Rips and Art Levitt presented "The Twin Towers Cluster in Torah Codes", and Art Levitt published "Component Analysis of Torah Code Phrases".[14] Each of the three works is supported by noted high technology entrepreneur Yuri Pikover, founder of Xylan (acquired in 1999 by Alcatel)[15][16]

[edit] Criticism

The primary objection advanced against Bible codes is that information theory does not prohibit "noise" from appearing to be sometimes meaningful. Thus, if data chosen for ELS experiments are intentionally or unintentionally "cooked" before the experiment is defined, similar patterns can be found in texts other than the Torah. Although the probability of an ELS in a random place being a meaningful word is small, there are so many possible starting points and skip patterns that many such words can be expected to appear, depending on the details chosen for the experiment, and that it is possible to "tune" an ELS experiment to achieve a result which appears to exhibit patterns that overcome the level of noise.

[edit] Criticism of the original paper

In 1999, Australian mathematician Brendan McKay, together with mathematicians Dror Bar-Natan and Gil Kalai, and psychologist Maya Bar-Hillel (collectively known as "MBBK") published a paper in Statistical Science, in which they argue that the case of Witztum, Rips and Rosenberg (WRR) is "fatally defective, indeed that their result merely reflects on the choices made in designing their experiment and collecting the data for it."[17] The MBBK paper was reviewed anonymously by four professional statisticians prior to publication.

In the MBBK paper, the authors present the following arguments:

- The authors argue that because of problems in WRR's test method, the results of WRR's 1994 paper "may reflect (at least to some extent) uninteresting properties of the word list [the appellation-date word pairs] rather than an extraordinary property of Genesis,"[18] and that the test method used by WRR has properties that make it "exceptionally susceptible to systematic bias."[19]

- The authors argue that WRR had many choices available when selecting the appellations, the dates, and the date forms.[20]

- The authors argue that, despite the claims by WRR and S. Z. Havlin that Havlin prepared the appellations independently, the earliest available documents on the experiments do not state that the lists of appellations were prepared by an independent expert. Similarly, the authors quote a 1985 lecture by Eliyahu Rips, in which he describes the appellation selection process as taking "every possible variant that we considered reasonable," and makes no mention of Havlin or an independent expert.[21]

- The authors report that, by adding some appellations and removing some appellations from WRR's list 2, and then repeating the test on the initial 78,064 letters (the length of Genesis) of a Hebrew translation of War and Peace, they achieved a significance level of one in a million. The authors say this shows that "the freedom provided just in the selection of appellations is sufficient to explain the strong result" in WRR's 1994 paper.[22]

- The authors present a "study of variations," in which they repeated the experiments many times, each time making one or more minimal changes to the test method, the dates, or the date forms.[23] The authors conclude that "only a small fraction of variations made WRR's result stronger and then usually by only a small amount ... we believe that these observations are strong evidence for tuning ... "[24]

- The authors present experiments they conducted which they say show that some results of experiments by WRR and Harold Gans are "too good to be true." That is, some of the results are statistically improbable even if one accepts that WRR's hypothesis is true. The authors say that these studies "give support to the theory that WRR's experiments were tuned toward an overly idealized result consistent with the common expectations of statistically naive researchers."[25]

- The authors present multiple experiments they conducted in which they attempted to replicate WRR's experiments. The authors used an independent expert to prepare the appellations and dates for each of these experiments. The authors report that the results of these attempted replications were negative.[26]

- The authors argue that the available evidence indicates that the text of Genesis used by WRR is substantially different from its original form, and that ELSs with large skips (which WRR's experiments rely on) could not survive such changes.[27]

From these observations, MBBK created an alternative hypothesis to explain the "puzzle" of how the codes were discovered. MBBK's claim, in essence, was that the WRR authors had "cheated"[28]. MBBK went on to describe the means by which the cheating might have occurred, and demonstrate the tactic as presumed.

MBBK's refutation was not strictly mathematical in nature, rather it asserted that the WRR authors and contributors had intentionally or unintentionally (a) selected the names and/or dates in advance and (b) designed their experiments to match their selection and thereby achieved their "desired" result. The MBBK paper argued that the ELS experiment is extraordinarily sensitive to very small changes in the spellings of appellations, and that the WRR result "merely reflects on the choices made in designing their experiment and collecting the data for it."

The MBBK paper demonstrated that this "tuning", when combined with what MBBK asserted was available "wiggle" room, was capable of generating a result similar to WRR's Genesis result in a Hebrew translation of War and Peace. Psychologist and MBBK co-author Maya Bar-Hillel subsequently summarized the MBBK view that the WRR paper was a hoax, an intentionally and a carefully designed "magic trick"[29].

The Bible codes (together with similar arguments concerning hidden prophecies in the writings of Shakespeare) have been quoted as examples of the Texas sharpshooter fallacy.

[edit] Replies to MBBK's criticisms

Harold Gans has argued that MBBK's hypothesis implies a conspiracy between WRR and their co-contributors to fraudulently tune the appellations in advance. Gans argues that the conspiracy must include Doron Witztum, Eliyahu Rips, and S. Z. Havlin, because all of them say that Havlin compiled the appellations independently. Gans argues further that such a conspiracy must include the multiple rabbis who have written a letter confirming the accuracy of Havlin's list. Finally, argues Gans, such a conspiracy must also include the multiple participants of the cities experiment conducted by Gans (which includes Gans himself). Gans concludes that "the number of people necessarily involved in [the conspiracy] will stretch the credulity of any reasonable person."[30]

Brendan McKay has replied that he and his colleagues have never accused Havlin or Gans of participating in a conspiracy. Instead, says McKay, Havlin likely did what WRR's early preprints said he did: he provided "valuable advices." Similarly, McKay accepts Gans' statements that Gans did not prepare the data for his cities experiment himself. McKay concludes that "there is only ONE person who needs to have been involved in knowing fakery, and a handful of his disciples who must be involved in the cover-up (perhaps with good intent)."[31]

Responding to the MBBK allegations of trickery, WRR authors issued a series of detailed refutations of the claims of MBBK, including evidence that no such tuning did or even could have taken place. An earlier WRR response to a request by MBBK authors, presented results from additional experiments that used the specific "alternate" name and date formats which MBBK suggested had been intentionally avoided by WRR. Using MBBK's alternates, the results WRR returned showed equivalent or better support for the existence of the codes, and so challenged the "wiggle room" assertion of MBBK. In the wake of the WRR response, author Bar-Natan issued a formal statement of non-response. After a series of exchanges with McKay and Bar-Hillel, WRR author Witztum responded in a new paper claiming that McKay had used smoke screen tactics in creating several Straw Man arguments, and thereby avoided the points made by WRR authors refuting MBBK. Witztum also claimed that, upon interviewing a key independent expert contracted by McKay for the MBBK paper, that some experiments performed for MBBK had validated, rather than refuted the original WRR findings, and questioned why MBBK had expunged these results from their paper.

By 1999, meaningful debate mostly disappeared into personal attacks and diatribes as the participants accused one another of all manner of madness, deceptions and ill intent.

[edit] Criticism of Michael Drosnin

Journalist Drosnin's books have been criticized by some who believe that the Bible Code is real but that it cannot predict the future.[32] Some accuse him of factual errors, claiming that he has much support in the scientific community,[33] mistranslating Hebrew words [34] to make his point more convincing, and using the Bible without proving that other books do not have similar codes.[35]

Responding to an explicit challenge from Drosnin, who claimed that other texts such as Moby-Dick would not yield ELS results comparable to the Torah, McKay created a new experiment that was tuned to find many ELS letter arrays in Moby Dick that relate to modern events, including the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. He also found a code relating to the Rabin assassination, containing the assassin's first and last name and the university he attended, as well as the motive ("Oslo", relating to the Oslo accords).[36] Drosnin and others have responded to these claims, saying the tuning tactics employed by McKay were simply "nonsense", and providing analyses to support their argument that the tables, data and methodologies McKay used to produce the Moby Dick results "simply do not qualify as code tables". [37]

Skeptic Dave Thomas claimed to find other examples in many texts, though Thomas' methodology was refuted by Robert Haralick [38] and others. In addition, McKay claimed that Drosnin had used the flexibility of Hebrew orthography to his advantage, freely mixing classic (no vowels, Y and W strictly consonant) and modern (Y and W used to indicate i and u vowels) modes, as well as variances in spelling of K and T, to reach the desired meaning. In his television series John Safran vs God, Australian television personality John Safran and McKay again demonstrated the 'tuning' technique, demonstrating that these techniques could produce "evidence" of the September 11 terrorist attacks on New York in the lyrics of Vanilla Ice's repertoire. Additionally, 'coded' references in non-Torah Bible texts, as for instance the famous Number of the Beast, do not use the Bible code technique. And, the influence and consequences of scribal errors (eg, misspellings, additions, deletions, misreadings, ...) are hard to account for in the context of a Bible coded message left secretly in the text. McKay and others claim that in the absence of an objective measure of quality and an objective way to select test subjects, it is not possible to positively determine whether any particular observation is significant or not. For that reason, most of the serious effort of the skeptics has been focused on the scientific claims of Witztum, Rips and Gans.

[edit] Predictions versus probabilities

Traditional codes scholars and adherents believe that the codes cannot (and should not) be used for "soothsaying". The traditional view that the codes are "useless for prediction", and the basis for it, were described by Jeffrey Satinover in his 1997 book "Cracking the Bible Code"[39]. This view holds that, at best, signs of the existence of encrypted information in the Torah indicate evidence supporting the existence of an all-knowing creator.

Nonetheless, the use and publication of "predictions" based on Bible codes has succeeded in bringing about popular awareness of the codes, most notably based on the work of journalist Michael Drosnin. Drosnin, who says he is "not at all religious" and does not believe in God, has offered speculations on the source of the codes but no answers, saying "I'm a reporter and can't go past the hard evidence. There is a code, therefore there is an encoder. I don't know who or what it/he/she is."[40]

Drosnin's most famous prediction, in 1994, was the 1995 assassination of Israeli Prime Minister, Yitzhak Rabin, using a Bible code technique.[34] Drosnin uses this prediction as evidence for the validity of his bible code techniques.[41] Opponents claim that in the political atmosphere of the time, predicting with no additional details the fact that Rabin would be assassinated is not compelling, though dramatic.[citation needed].

Drosnin, in "The Bible Code II", described the probabilities of nuclear holocausts and the destruction of major cities by earthquakes in 2006, saying "The dangers will peak in the Hebrew year 5766 (September 2005 - September 2006 in the modern calendar), the year that is most clearly encoded with both 'World War' and 'Atomic Holocaust'… "The Bible Code is not a prediction that we will all die in 2006. It is a warning that we might all die in 2006, if we do not change our future." [40]

More recently, Drosnin has refrained from making concrete predictions, saying, "I don't think the code makes predictions. I think it reveals probabilities." Drosnin also said "I think it might tell us all our possible futures."[41]

[edit] See also

- Bibliomancy

- Confirmation bias

- Cryptography

- Eliyahu Rips

- Gematria

- Jeffrey Satinover

- Lord's Witnesses

- Pi (film)

- Pseudoscience

- Shemhamphorasch

- Summary of Christian eschatological differences

- Texas sharpshooter fallacy

- Theomatics

Relevant topics:

- Ergodic theory, which forms the foundation for modern information theory

- Information theory, which involves various statistical properties of long sequences of text

- Ramsey theory, for an interesting and important notion of "unavoidable coincidences"

- Symbolic dynamics, a subfield of ergodic theory which deals with (possibly multidimensional) symbolic sequences

- Holographic principle, in which John Archibald Wheeler and others posit that the universe may be made of information rather than matter and energy.

[edit] References

- ^ Doron Witztum, Eliyahu Rips, Yoav Rosenberg (1994). "Equidistant letter sequences in the Book of Genesis". Statistical Science 9: 429–438. doi:.

- ^ Shak, Moshe Aharon. 2004. Bible Codes Breakthrough. Montreal: Green Shoelace Books. 38

- ^ Haralick, Rips, and Glazerson. 2005. Torah Codes: A glimpse into the infinite. New York: Mazal & Bracha. 125

- ^ Sherman, R. Edwin, with Jacobi and Swaney. 2005. Bible Code Bombshell Green Forest, Ar.: New Leaf Press. 95-109

- ^ http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Extras/Keynes_Newton.html John Maynard Keynes on Newton's cryptogram beliefs

- ^ Kass, R.E. (1999). Introduction to "Solving the Bible Code Puzzle" by Brendan McKay, Dror Bar-Natan, Maya Bar-Hillel and Gil Kalai. Statistical Science 14, 149.

- ^ http://www.aish.com/seminars/discovery/Codes/codes.htm

- ^ [1] Public Statement by Dr. Rips on Michael Drosnin's theories

- ^ What are Bible Codes?

- ^ http://www.biblecodedigest.com BibleCodeDigest.com

- ^ Sherman, R. Edwin, with Jacobi and Swaney. 2005. Bible Code Bombshell Green Forest, Ar.: New Leaf Press. 281-286

- ^ "Analysis of the "Gans" Committee Report", Analysis of the "Gans" Committee Report, 2004-7-19

- ^ Adlerstein, Yitzchok (2005-10-11). "Nobel Prize Settles Bible Codes Dispute (almost)". Cross currents (web). http://www.cross-currents.com/archives/2005/10/11/nobel-prize-settles-bible-codes-dispute. Retrieved on 2008-02-24.

- ^ http://scholar.google.com/scholar?sourceid=navclient&ie=UTF-8&rls=ADBS,ADBS:2006-43,ADBS:en&q=%22yuri+pikover%22+gans&um=1&sa=N&tab=ws

- ^ pikover xylan alcatel billion - Google News Archive Search

- ^ http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&lr=&oi=qs&q=yuri+pikover

- ^ B. McKay, D. Bar-Natan, M. Bar-Hillel, and G. Kalai (1999). "Solving the Bible Code Puzzle." Statistical Science, 14, 150-173.

- ^ B. McKay, D. Bar-Natan, M. Bar-Hillel, and G. Kalai (1999). "Solving the Bible Code Puzzle." Statistical Science, 14, 154.

- ^ B. McKay, D. Bar-Natan, M. Bar-Hillel, and G. Kalai (1999). "Solving the Bible Code Puzzle." Statistical Science, 14, 155.

- ^ B. McKay, D. Bar-Natan, M. Bar-Hillel, and G. Kalai (1999). "Solving the Bible Code Puzzle." Statistical Science, 14, 155-157.

- ^ B. McKay, D. Bar-Natan, M. Bar-Hillel, and G. Kalai (1999). "Solving the Bible Code Puzzle." Statistical Science, 14, 156.

- ^ B. McKay, D. Bar-Natan, M. Bar-Hillel, and G. Kalai (1999). "Solving the Bible Code Puzzle." Statistical Science, 14, 157.

- ^ B. McKay, D. Bar-Natan, M. Bar-Hillel, and G. Kalai (1999). "Solving the Bible Code Puzzle." Statistical Science, 14, 157-161, 168-171.

- ^ B. McKay, D. Bar-Natan, M. Bar-Hillel, and G. Kalai (1999). "Solving the Bible Code Puzzle." Statistical Science, 14, 161.

- ^ B. McKay, D. Bar-Natan, M. Bar-Hillel, and G. Kalai (1999). "Solving the Bible Code Puzzle." Statistical Science, 14, 161-162.

- ^ B. McKay, D. Bar-Natan, M. Bar-Hillel, and G. Kalai (1999). "Solving the Bible Code Puzzle." Statistical Science, 14, 164.

- ^ B. McKay, D. Bar-Natan, M. Bar-Hillel, and G. Kalai (1999). "Solving the Bible Code Puzzle." Statistical Science, 14, 165-166.

- ^ http://www.ma.huji.ac.il/~kalai/aumann.txt

- ^ Madness in the Method at http://www.dartmouth.edu/~chance/teaching_aids/books_articles/Maya.html

- ^ H. J. Gans. A Primer on the Torah Codes Controversy for Laymen (part 1). Retrieved April 7, 2008.

- ^ B. McKay (2003). Brief notes on Gans' Primer. Retrieved April 7, 2008.

- ^ The Bible Code

- ^ Torah Codes

- ^ a b Review of Michael Drosnin's Bible Code

- ^ Barry Simon on Torah Codes

- ^ Assassinations Foretold in Moby Dick

- ^ CNN.com

- ^ http://www.torah-code.org/papers/skeptical_inquirer_02_15_07.pdf

- ^ See "A Talk with Dr. Jeffrey Satinover at http://www.quantgen.com/TALK.HTM

- ^ a b A Futurist's View, The Bible Code, Mayan Prophecy and My Vision of World War III

- ^ a b CNN - Meet Michael Drosnin Author, "The Bible Code"

- Drosnin, Michael (1997). The Bible Code. USA: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-81079-4.

- Satinover, Jeffrey (1997). Cracking the Bible Code. New York: W. Morrow. ISBN 0-688-15463-8.

- Drosnin, Michael (1997). The Bible Code. UK: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-81995-X.

- Drosnin, Michael (2002). The Bible Code II: The Countdown. USA: Viking Books. ISBN 0-670-03210-7.

- Drosnin, Michael (2002). The Bible Code II: The Countdown. UK: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-84249-8.

- Drosnin, Michael (Forthcoming 2006). The Bible Code III: The Quest. UK: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-84784-8.

- Stanton, Phil (1998). The Bible Code - Fact or Fake?. Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books. ISBN 0-89107-925-4.

- Haralick, Robert M.; Rips, Eliyahu; and Glazerson, Matiyahu (2005). Torah Codes: A Glimpse into the Infinite. Mazal & Bracha Publishing. ISBN 0-9740493-9-5.

[edit] External links

- The Bible Code, transcript of a story which aired on BBC Two, Thursday 20 November 2003, featuring comments by Drosnin, Rips, and McKay.

- Doron Witztum's codes page from Doron Witzum, a coauthor of the Statistical Sciences paper

- Tutorial Website from Professor Robert Haralick

- "Scientific Refutation of the Bible Codes" by Brendan McKay (Computer Science, Australian National University) and others

- The Bible Code: A Book Review by Allyn Jackson, plus Comments on the Bible Code by Shlomo Sternberg, Notices of the AMS September 1997 (see the American Mathematical Society)

- The Bible "Codes": a Textual Perspective, by Jeffrey H. Tigay (Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, University of Pennsylvania)

- Hidden Messages and The Bible Code from Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, publisher of Skeptical Inquirer Magazine

- Trying to stay objective, by Remy Wilders (Computer Science, France)