Wandering Jew

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Wandering Jew is a figure from medieval Christian folklore whose legend began to spread in Europe in the thirteenth century and became a fixture of Christian mythology, and, later, of Romanticism. The original legend concerns a Jew who taunted Jesus on the way to the Crucifixion and was then cursed to walk the earth until the Second Coming. The exact nature of the wanderer's indiscretion varies in different versions of the tale, as do aspects of his character; sometimes he is said to be a shoemaker or other tradesman, sometimes he is the doorman at Pontius Pilate's estate.

Contents |

[edit] Origin of the legend

The origins of the legend are debatable; perhaps one element is the story in Genesis of Cain, who is issued with a similar punishment — to wander over the earth, never reaping a harvest again, but scavenging. According to some sources, the legend stems from Jesus's words given in Matthew 16:28:

- 'Verily I say unto you, There be some standing here, which shall not taste of death, till they see the Son of Man coming in his kingdom.'(King James Version)[1]

A belief that the disciple whom Jesus loved would not die before the Second Coming was apparently popular enough in the early Christian world to be denounced in the Gospel of John:

- 20. And Peter, turning about, seeth the disciple following whom Jesus loved, who had also leaned on His breast at the supper, and had said, Lord, which is he who betrayeth Thee? 21. When, therefore, Peter saw him, he said to Jesus, Lord, and what shall he do? 22. Jesus saith to him, If I will that he remain till I come, what is that to thee? follow thou Me. 23. Then this saying went forth among the brethren, that that disciple would not die; yet Jesus had not said to him that he would not die; but, If I will that he tarry till I come, what is that to thee? (John 21:20-23, KJV)

A variant of the Wandering Jew legend is recorded in the Flores Historiarum by Roger of Wendover around the year 1228.[2][3] An Armenian archbishop, then visiting England, was asked by the monks of St Albans Abbey about the celebrated Joseph of Arimathea, who had spoken to Jesus, and was reported to be still alive. The archbishop answered that he had himself seen him in Armenia, and that his name was Cartaphilus, a Jewish shoemaker, who, when Jesus stopped for a second to rest while carrying his cross, hit him, and told him "Go on quicker, Jesus! Go on quicker! Why dost Thou loiter?", to which Jesus, "with a stern countenance," is said to have replied: "I shall stand and rest, but thou shalt go on till the last day." The Armenian bishop also reported that Cartaphilus had since converted to Christianity and spent his wandering days proselytizing and leading a hermit's life.

Matthew Paris included this passage from Roger of Wendover in his own history; and other Armenians appeared in 1252 at the Abbey of St Albans, repeating the same story, which was regarded there as a great proof of the truth of the Christian religion.[4] The same Armenian told the story at Tournai in 1243, according to the Chronicles of Phillip Mouskes, (chapter ii. 491, Brussels, 1839). After that, Guido Bonatti writes people saw the Wandering Jew in Forlì (Italy), in the XIII Century; other people saw him in Vienna and otherwhere.[citation needed]

The figure of the doomed sinner, forced to wander without the hope of rest in death till the second coming of Christ, impressed itself upon the popular medieval imagination, mainly with reference to the seeming immortality of the wandering Jewish people. These two aspects of the legend are represented in the different names given to the central figure. In German-speaking countries he is referred to as "Der Ewige Jude" (the immortal, or eternal, Jew), while in Romance-speaking countries he is known as "Le Juif Errant" (the Wandering Jew) and "L'Ebreo Errante"; the English form, probably because it is derived from the French, has followed the Romance. The Spanish name is Juan [el que] Espera a Dios, "John [who] waits for God," or, more commonly, "El Judío Errante."

[edit] Name

At least from the seventeenth century the name Ahasver has been given to the Wandering Jew, apparently adapted from Ahasuerus, the Persian king in Esther, who is not a Jew, and whose very name among medieval Jews was an exemplum of a fool.[5]

A variety of names have since been given to the Wandering Jew, including Matathias, Buttadeus, and Isaac Laquedem (a name for him in France and the Low Countries, in popular legend as well as in a novel by Dumas, see below).

[edit] In literature

[edit] Before 1600

"The Pardoner's Tale," a story from The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer may contain a reference to the Wandering Jew. Many have attributed to the Wandering Jew the enigmatic character of the old man who is unable to die and wishes to trade his age for someone else's youth. He also disciplines the three rioters when they are rude to him and insult his circumstances, perhaps indicating he has learned his lesson from tormenting Jesus.

[edit] 17th and 18th centuries

The legend became more popular after it appeared in a pamphlet of four leaves, Kurtze [sic] Beschreibung und Erzählung von einem Juden mit Namen Ahasverus (Short description and tale of a Jew with the name Ahasuerus).[6] "Here we are told that some fifty years before, a bishop met him in a church at Hamburg, repentant, ill-clothed and distracted at the thought of having to move on in a few weeks"[7] As with urban legends, particularities lend verisimilitude: the bishop is specifically the Bishop of Schleswig, Paulus von Eizen. The legend spread quickly throughout Germany, no less than eight different editions appearing in 1602; altogether forty appeared in Germany before the end of the eighteenth century. Eight editions in Dutch and Flemish are known; and the story soon passed to France, the first French edition appearing in Bordeaux, 1609, and to England, where it appeared in the form of a parody in 1625.[8] The pamphlet was translated also into Danish and Swedish; and the expression "eternal Jew" is current in Czech and German, der Ewige Jude. Apparently the pamphlets of 1602 borrowed parts of the descriptions of the wanderer from reports (most notably by Balthasar Russow) about an itinerant preacher called Jürgen.[9]

In France, the Wandering Jew appeared in Simon Tyssot de Patot's La Vie, les Aventures et le Voyage de Groenland du Révérend Père Cordelier Pierre de Mésange (1720).

[edit] 19th century

[edit] English

The Wandering Jew makes an appearance in one of the secondary plots in Matthew Lewis's Gothic novel The Monk, first published in 1796. The Wandering Jew is also mentioned in "Melmoth the Wanderer" by Charles Maturin c. 1820.

In England — besides the ballad given in Thomas Percy's Reliques and reprinted in Francis James Child's English and Scotch Ballads (1st ed., viii. 77) — there is a drama entitled The Wandering Jew, or Love's Masquerade, written by Andrew Franklin (1797). Shelley introduced Ahasuerus into his "Queen Mab". Thomas Carlyle, in his Sartor Resartus (1834), compares its hero Diogenes Teufelsdroeckh on several occasions to the Wandering Jew, (also using the German wording 'der ewige Jude').

George Croly's "Salathiel", which appeared anonymously in 1828, treated the subject in an imaginative form; it was reprinted under the title "Tarry Thou Till I Come" (New York, 1901). George MacDonald includes pieces of the legend in Thomas Wingfold, Curate (London, 1876).

In Lew Wallace's novel The Prince of India, the Wandering Jew is the protagonist. The book follows his adventures through the ages, as he takes part in the shaping of history.

[edit] German

The legend has been the subject of German poems by Schubart, Aloys Schreiber, Wilhelm Müller, Lenau, Chamisso, Schlegel, Julius Mosen (an epic, 1838), and Köhler; of novels by Franz Horn (1818), Oeklers, and Schücking; and of tragedies by Klingemann ("Ahasuerus", 1827) and Zedlitz (1844). It is either the Ahasuerus of Klingemann or that of Ludwig Achim von Arnim in his play, Halle and Jerusalem to whom Richard Wagner refers in the final passage of his notorious essay Das Judentum in der Musik.

There are clear echoes of the Wandering Jew in Wagner's The Flying Dutchman, whose plot line is adapted from a story by Heinrich Heine[10], and his final opera Parsifal features a woman called Kundry who is in some ways a female version of the Wandering Jew. It is alleged that she was formerly Herodias, and she admits that she laughed at Jesus on his route to the Crucifixion, and is now condemned to wander until she meets with him again (cf. Eugene Sue's version, below).

Hans Christian Andersen made his "Ahasuerus" the Angel of Doubt, and was imitated by Heller in a poem on "The Wandering of Ahasuerus", which he afterward developed into three cantos. Robert Hamerling, in his "Ahasver in Rom" (Vienna, 1866), identifies Nero with the Wandering Jew. Goethe had designed a poem on the subject, the plot of which he sketched in his "Dichtung und Wahrheit".

In the section "The Shadow" of Friedrich Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra, a character referring to himself as Zarathustra's shadow likens himself to the Eternal Jew.

[edit] France

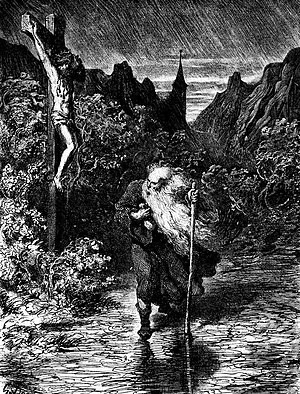

The French writer Edgar Quinet published his prose epic on the legend in 1833, making the subject the judgment of the world; and Eugène Sue wrote his Juif errant in 1844, in which the author connects the story of Ahasuerus with that of Herodias. Grenier's poem on the subject (1857) may have been inspired by Gustave Doré's designs published in the preceding year, perhaps the most striking of Doré's imaginative works. One should also note Paul Féval, père's La Fille du Juif Errant (1864), which combines several fictional Wandering Jews, both heroic and evil, and Alexandre Dumas' incomplete Isaac Laquedem (1853), a sprawling historical saga.

[edit] Russia

In Russia, the legend of the Wandering Jew appears in an incomplete epic poem by Vasily Zhukovsky, "Ahasuerus" (1857) and in another epic poem by Wilhelm Küchelbecker, "Ahasuerus, a Poem in Fragments," written from 1832-1846 but not published until 1878, long after the poet's death. Alexander Pushkin also began a long poem on Ahasuerus (1826) but abandoned the project quickly, completing under thirty lines.

[edit] Other literature

The Wandering Jew makes a notable appearance in the gothic masterpiece of the Polish writer Jan Potocki, The Manuscript Found in Saragossa, written about 1797.

Brazilian writer and poet Machado de Assis often used Jewish themes in his writings. One of his poems, Viver! ("To Live!") is a dialog between the Wandering Jew (named as Ahasuerus) and Prometheus at the end of time. It was published in 1896 as part of the book Várias histórias ("Several stories").

The Hungarian poet János Arany also wrote a ballad called "Az örök zsidó", meaning "The everlasting Jew".

The story of the Wandering Jew is also discussed in an early portion of Søren Kierkegaard's Either/Or (published 1843 in Copenhagen) that focuses on Mozart's opera Don Giovanni.

[edit] 20th century

[edit] Spanish

In Argentina, the topic of the Wandering Jew has appeared several times in the work of writer and professor Enrique Anderson Imbert, particularly in his short-story El Grimorio (The Grimoire), included in the eponymous book. Anderson Imbert refers to the Wandering Jew as El Judío Errante or Ahasvero (Ahasuerus) indiscriminately. Chapter XXXVII, El Vagamundo, in the collection of short stories, Misteriosa Buenos Aires, by the Argentine writer Manuel Mujica Lainez also centres round the wandering of the Jew. The great Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges named the main character and narrator of his short story "The Immortal" Joseph Cartaphilus (in the story he was a Roman military tribune who gained immortality after drinking from a magical river and dies in the 1920s). In 1967, the Wandering Jew appears as an unexplained magical realist townfolk legend in Gabriel García Márquez's 100 Years of Solitude.

[edit] German

The German writer Stefan Heym in his novel Ahasver (translated into English as The Wandering Jew)[11] maps a story of Ahasver and Lucifer against both ancient times and Marxist East Germany.

[edit] Romanian

Mircea Eliade presents in his novel Dayan (1979) a student's mystic and fantastic journey through time and space under the guidance of the Wandering Jew, in the search of a higher truth and of his own self.

[edit] Russian

The Soviet satirists Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov had their hero Ostap Bender tell the story of the Wandering Jew's death at the hands of Ukrainian nationalists in The Little Golden Calf. The novel Overburdened with Evil (1988) by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky involves a character in modern setting who turns out to be Ahasuerus, identified at the same time in a subplot with John the Divine.

[edit] English

In Evelyn Waugh's Helena, the Wandering Jew appears in a dream to the protagonist and shows her where to look for the Cross, the goal of her quest. In Joyce's masterpiece Ulysses, Bloom's nemesis, the Citizen, says of Bloom in his absence: "A wolf in sheep's clothing, says the citizen. That's what he is. Virag from Hungary! Ahasuerus I call him. Cursed by God." [12] In the post-apocalyptic science fiction book A Canticle for Leibowitz, written by Walter M. Miller, Jr. and published in 1959, a character that can be interpreted as being the Wandering Jew is the only one to appear in all three novellas. J. G. Ballard's short story The Lost Leonardo, published in The Terminal Beach (1964), centres on a search for the Wandering Jew. Barry Sadler has written a series of books featuring a character called Casca Rufio Longinius who is combination of two characters from Christian folklore, Longinus and the Wandering Jew. In January 1987 DC Comics produced a special issue of Secret Origins that gave The Phantom Stranger four possible origins. In one of these explanations, the Stranger confirms to a priest that he is the Wandering Jew. [13]

George Sylvester Viereck and Paul Eldridge wrote a trilogy of novels "My First Two Thousand Years, an Autobiography of the Wandering Jew", (1928), in which Solome (described as 'The Wandering Jewess'), together with an equally immortal servant and companion, appear. In Ilium by Dan Simmons, (2003), a woman who is addressed as the Wandering Jew plays a central role, though her real name is Savi.

George K. Anderson's The Legend of the Wandering Jew [14] is a scholarly survey of the literature of the Wandering Jew from legends to the modern era.

[edit] Japanese

The Japanese author Akutagawa Ryunosuke published a story called The Wandering Jew in the magazine Shincho (New Tide) in 1917. Most of the information about the Wandering Jew that Akutagawa uses in this story is taken from the account of the legend given by Sabine Baring-Gould in Curious Myths of the Middle Ages. Among references taken from Baring-Gould are those to Gustave Doré's woodcuts, Sue's Le Juif Errant, Croly's Salathiel and Lewis's The Monk. Akutagawa postulates as the reason for Jesus's condemning 'Joseph' to wander the earth till the Second Coming the fact that he alone among all those involved in the crucifixion was aware of the nature of the sin he was committing.

[edit] In film, on stage and in music

Fromental Halévy's opera, Le juif errant, based on the novel by Sue, was premiered at the Paris Opera on 23 April 1852, and had 48 further performances over two seasons. The music was sufficiently popular to generate a Wandering Jew Mazurka, a Wandering Jew Waltz, and a Wandering Jew Polka. [15]

There have been several films on the topic of The Wandering Jew. A 1934 British version, starring Conrad Veidt in the title role, and entitled The Eternal Jew, is based on the stage play by E. Temple Thurston, and attempts to tell the legend literally, taking the Jew from Biblical times all the way to the Spanish Inquisition. This version was also made as a silent film in 1923, starring Matheson Lang in his original stage role. The play had been produced both in London and on Broadway. Co-produced in the U.S. by David Belasco, it had played on Broadway in 1921. Still another film version of the story, made in Italy in 1948, starred Vittorio Gassman.

A propaganda 'documentary' film made in Germany in 1940 and entitled Der Ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew), reflected crude National Socialist anti-Semitism, linking the legend with alleged Jewish malpractices over the ages.

In the 1988 film The Seventh Sign the Wanfering Jew appears as a Father Lucci, who identifies himself as the centuries old Cartaphilus, Pilate's porter, who took part in the scourging of Jesus before his crucifixion (a combination of the Wandering Jew and the Longinus legend). He wishes to assist in bringing about the end of the world in order that his interminable wandering might come to an end as well.

Glen Berger's 2001 play Underneath the Lintel is a monologue by a Dutch librarian who delves into the history of a book which is returned 113 years overdue, and becomes convinced that the borrower was the Wandering Jew. It has been performed on Off-Broadway, in the London West End, the Alley Theatre in Houston [16] and on BBC Radio 4 [17].

The Finnish doom metal band Reverend Bizarre has a song called "The Wandering Jew", that tells the story from the perspective of the namesake character. The song can be found on their EP Harbinger of Metal.

[edit] Notes

- ^ This verse is quoted in the German pamphlet Kurtze Beschreibung und Erzählung von einem Juden mit Namen Ahasverus, 1602.

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ Matthew Paris, Chron. Majora, ed. H. R. Luard, London, 1880, v. 340-341

- ^ David Daube, "Ahasver" The Jewish Quarterly Review New Series 45.3 (January 1955), pp 243-244.

- ^ This professes to have been printed at Leiden in 1602 by an otherwise unrecorded printer "Christoff Crutzer"; the real place and printer can not be ascertained.

- ^ Daube 1955:244.

- ^ Jacobs and Wolf, Bibliotheca Anglo-Judaica, p. 44, No. 221.

- ^ Beyer, Jürgen, 'Jürgen und der Ewige Jude. Ein lebender Heiliger wird unsterblich', Arv. Nordic Yearbook of Folklore 64 (2008), 125-40

- ^ Heinrich Heine, Aus den Memoiren des Herren von Schnabelewopski, 1834. See Barry Millington, The Wagner Compendium, London (1992), p. 277

- ^ Northwestern University Press (1983) ISBN 9780810117068

- ^ James Joyce, Ulysses, Bodley Head Ed., page 439

- ^ Barr, Mike W. (w), Aparo, Jim (p), Ziuko, Tom (i). "The Phantom Stranger". Secret Origins vol. 2, #10. (January, 1987). DC Comics. (2-10).

- ^ Brown University Press, 3rd printing 1991

- ^ Anderson, (1991), p. 259.

- ^ Alley Theatre - Underneath the Lintel

- ^ Saturday Play, starring Richard Schiff, 5th Jan 2008

[edit] References

- Anderson, George K. The Legend of the Wandering Jew. Providence: Brown University Press, 1965. xi, 489 p.; reprint edition ISBN 0-87451-547-5 Collects both literary versions and folk versions.

- Hasan-Rokem, Galit and Alan DundesThe Wandering Jew: Essays in the Interpretation of a Christian Legend (Bloomington:Indiana University Press) 1986. Twentieth-century folkloristic renderings.

[edit] External links

- The Wandering Jew, by Eugène Sue at Project Gutenberg

- Catholic Encyclopedia entry

- The (presumed) End of the Wandering Jew from The Golden Calf by Ilf and Petrov

- The legend of the wandering Jew in Europe and in Romania

- The Wandering Jew FAQ

- Wandering Jew and Wandering Jewess

- "The Wandering Image: Converting the Wandering Jew" Iconography and visual art.