Density functional theory

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Density functional theory (DFT) is a quantum mechanical theory used in physics and chemistry to investigate the electronic structure (principally the ground state) of many-body systems, in particular atoms, molecules, and the condensed phases. With this theory, the properties of a many-electron system can be determined by using functionals, i.e. functions of another function, which in this case is the spatially dependent electron density. Hence the name density functional theory comes from the use of functionals of the electron density. DFT is among the most popular and versatile methods available in condensed-matter physics, computational physics, and computational chemistry.

DFT has been very popular for calculations in solid state physics since the 1970s. In many cases the results of DFT calculations for solid-state systems agreed quite satisfactorily with experimental data. Also, the computational costs were relatively low when compared to traditional ways which were based on the complicated many-electron wavefunction, such as Hartree-Fock theory and its descendants. However, DFT was not considered accurate enough for calculations in quantum chemistry until the 1990s, when the approximations used in the theory were greatly refined to better model the exchange and correlation interactions. DFT is now a leading method for electronic structure calculations in chemistry and solid-state physics.

Despite the improvements in DFT, there are still difficulties in using density functional theory to properly describe intermolecular interactions, especially van der Waals forces (dispersion); charge transfer excitations; transition states, global potential energy surfaces and some other strongly correlated systems; and in calculations of the band gap in semiconductors. Its poor treatment of dispersion renders DFT unsuitable (at least when used alone) for the treatment of systems which are dominated by dispersion (e.g., interacting noble gas atoms) or where dispersion competes significantly with other effects (e.g. in biomolecules). The development of new DFT methods designed to overcome this problem, by alterations to the functional or by the inclusion of additive terms, is a current research topic.

Contents |

[edit] Overview of method

Although density functional theory has its conceptual roots in the Thomas-Fermi model, DFT was put on a firm theoretical footing by the two Hohenberg-Kohn theorems (H-K).[1] The original H-K theorems held only for non-degenerate ground states in the absence of a magnetic field, although they have since been generalized to encompass these.[2][3]

The first H-K theorem demonstrates that the ground state properties of a many-electron system are uniquely determined by an electron density that depends on only 3 spatial coordinates. It lays the groundwork for reducing the many-body problem of N electrons with 3N spatial coordinates to only 3 spatial coordinates, through the use of functionals of the electron density. This theorem can be extended to the time-dependent domain to develop time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT), which can be used to describe excited states.

The second H-K theorem defines an energy functional for the system and proves that the correct ground state electron density minimizes this energy functional.

Within the framework of Kohn-Sham DFT, the intractable many-body problem of interacting electrons in a static external potential is reduced to a tractable problem of non-interacting electrons moving in an effective potential. The effective potential includes the external potential and the effects of the Coulomb interactions between the electrons, e.g., the exchange and correlation interactions. Modeling the latter two interactions becomes the difficulty within KS DFT. The simplest approximation is the local-density approximation (LDA), which is based upon exact exchange energy for a uniform electron gas, which can be obtained from the Thomas-Fermi model, and from fits to the correlation energy for a uniform electron gas. Non-interacting systems are relatively easy to solve as the wavefunction can be represented as a Slater determinant of orbitals. Further, the kinetic energy functional of such a system is known exactly. The exchange-correlation part of the total-energy functional remains unknown and must be approximated.

Another approach, less popular than Kohn-Sham DFT (KS-DFT) but arguably more closely related to the spirit of the original H-K theorems, is orbital-free density functional theory (OFDFT), in which approximate functionals are also used for the kinetic energy of the non-interacting system.

[edit] Derivation and formalism

As usual in many-body electronic structure calculations, the nuclei of the treated molecules or clusters are seen as fixed (the Born-Oppenheimer approximation), generating a static external potential V in which the electrons are moving. A stationary electronic state is then described by a wavefunction  satisfying the many-electron Schrödinger equation

satisfying the many-electron Schrödinger equation

where  is the electronic molecular Hamiltonian,

is the electronic molecular Hamiltonian,  is the number of electrons,

is the number of electrons,  is the

is the  -electron kinetic energy,

-electron kinetic energy,  is the

is the  -electron potential energy from the external field, and

-electron potential energy from the external field, and  is the electron-electron interaction energy for the

is the electron-electron interaction energy for the  -electron system. The operators

-electron system. The operators  and

and  are so-called universal operators as they are the same for any system, while

are so-called universal operators as they are the same for any system, while  is system dependent, i.e. non-universal. The difference between having separable single-particle problems and the much more complicated many-particle problem arises from the interaction term

is system dependent, i.e. non-universal. The difference between having separable single-particle problems and the much more complicated many-particle problem arises from the interaction term  .

.

There are many sophisticated methods for solving the many-body Schrödinger equation based on the expansion of the wavefunction in Slater determinants. While the simplest one is the Hartree-Fock method, more sophisticated approaches are usually categorized as post-Hartree-Fock methods. However, the problem with these methods is the huge computational effort, which makes it virtually impossible to apply them efficiently to larger, more complex systems.

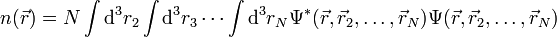

Here DFT provides an appealing alternative, being much more versatile as it provides a way to systematically map the many-body problem, with  , onto a single-body problem without

, onto a single-body problem without  . In DFT the key variable is the particle density

. In DFT the key variable is the particle density  , which for a normalized

, which for a normalized  is given by

is given by

This relation can be reversed, i.e. for a given ground-state density  it is possible, in principle, to calculate the corresponding ground-state wavefunction

it is possible, in principle, to calculate the corresponding ground-state wavefunction  . In other words,

. In other words,  is a unique functional of

is a unique functional of  ,[1]

,[1]

and consequently the ground-state expectation value of an observable  is also a functional of

is also a functional of

In particular, the ground-state energy is a functional of

where the contribution of the external potential ![\left\langle \Psi[n_0] \left|\hat V \right| \Psi[n_0] \right\rangle](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/c/d/0/cd0cd966517148fb95c7c4d15bd1e44f.png) can be written explicitly in terms of the ground-state density

can be written explicitly in terms of the ground-state density

More generally, the contribution of the external potential  can be written explicitly in terms of the density

can be written explicitly in terms of the density  ,

,

The functionals ![\,\!T[n]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/2/2/2/2220bca035dc1ca4b3c43a0465cf7de4.png) and

and ![\,\!U[n]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/8/c/3/8c380361593608570ffd1e2013557443.png) are called universal functionals, while

are called universal functionals, while ![\,\!V[n]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/b/4/0/b40fbd957f5970efeed776fa2de69c73.png) is called a non-universal functional, as it depends on the system under study. Having specified a system, i.e., having specified

is called a non-universal functional, as it depends on the system under study. Having specified a system, i.e., having specified  , one then has to minimize the functional

, one then has to minimize the functional

with respect to  , assuming one has got reliable expressions for

, assuming one has got reliable expressions for ![\,\!T[n]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/2/2/2/2220bca035dc1ca4b3c43a0465cf7de4.png) and

and ![\,\!U[n]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/8/c/3/8c380361593608570ffd1e2013557443.png) . A successful minimization of the energy functional will yield the ground-state density

. A successful minimization of the energy functional will yield the ground-state density  and thus all other ground-state observables.

and thus all other ground-state observables.

The variational problems of minimizing the energy functional ![\,\!E[n]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/5/1/9/51999f8192d36af3a519560759a0ef40.png) can be solved by applying the Lagrangian method of undetermined multipliers.[4] First, one considers an energy functional that doesn't explicitly have an electron-electron interaction energy term,

can be solved by applying the Lagrangian method of undetermined multipliers.[4] First, one considers an energy functional that doesn't explicitly have an electron-electron interaction energy term,

where  denotes the non-interacting kinetic energy and

denotes the non-interacting kinetic energy and  is an external effective potential in which the particles are moving. Obviously,

is an external effective potential in which the particles are moving. Obviously,  if

if  is chosen to be

is chosen to be

Thus, one can solve the so-called Kohn-Sham equations of this auxiliary non-interacting system,

which yields the orbitals  that reproduce the density

that reproduce the density  of the original many-body system

of the original many-body system

The effective single-particle potential can be written in more detail as

where the second term denotes the so-called Hartree term describing the electron-electron Coulomb repulsion, while the last term  is called the exchange-correlation potential. Here,

is called the exchange-correlation potential. Here,  includes all the many-particle interactions. Since the Hartree term and

includes all the many-particle interactions. Since the Hartree term and  depend on

depend on  , which depends on the

, which depends on the  , which in turn depend on

, which in turn depend on  , the problem of solving the Kohn-Sham equation has to be done in a self-consistent (i.e., iterative) way. Usually one starts with an initial guess for

, the problem of solving the Kohn-Sham equation has to be done in a self-consistent (i.e., iterative) way. Usually one starts with an initial guess for  , then calculates the corresponding

, then calculates the corresponding  and solves the Kohn-Sham equations for the

and solves the Kohn-Sham equations for the  . From these one calculates a new density and starts again. This procedure is then repeated until convergence is reached.

. From these one calculates a new density and starts again. This procedure is then repeated until convergence is reached.

[edit] Approximations (Exchange-correlation functionals)

The major problem with DFT is that the exact functionals for exchange and correlation are not known except for the free electron gas. However, approximations exist which permit the calculation of certain physical quantities quite accurately. In physics the most widely used approximation is the local-density approximation (LDA), where the functional depends only on the density at the coordinate where the functional is evaluated:

The local spin-density approximation (LSDA) is a straightforward generalization of the LDA to include electron spin:

Highly accurate formulae for the exchange-correlation energy density  have been constructed from quantum Monte Carlo simulations of a free electron model.[5]

have been constructed from quantum Monte Carlo simulations of a free electron model.[5]

Generalized gradient approximations (GGA) are still local but also take into account the gradient of the density at the same coordinate:

Using the latter (GGA) very good results for molecular geometries and ground-state energies have been achieved.

Potentially more accurate than the GGA functionals are meta-GGA functions. These functionals include a further term in the expansion, depending on the density, the gradient of the density and the Laplacian (second derivative) of the density.

Difficulties in expressing the exchange part of the energy can be relieved by including a component of the exact exchange energy calculated from Hartree-Fock theory. Functionals of this type are known as hybrid functionals.

[edit] Generalizations to include magnetic fields

The DFT formalism described above breaks down, to various degrees, in the presence of a vector potential, i.e. a magnetic field. In such a situation, the one-to-one mapping between the ground-state electron density and wavefunction is lost. Generalizations to include the effects of magnetic fields have led to two different theories: current density functional theory (CDFT) and magnetic field functional theory (BDFT). In both these theories, the functional used for the exchange and correlation must be generalized to include more than just the electron density. In current density functional theory, developed by Vignale and Rasolt,[3] the functionals become dependent on both the electron density and the paramagnetic current density. In magnetic field density functional theory, developed by Salsbury, Grayce and Harris, the functionals depend on the electron density and the magnetic field, and the functional form can depend on the form of the magnetic field. In both of these theories it has been difficult to develop functionals beyond their equivalent to LDA, which are also readily implementable computationally.

[edit] Applications

In practice, Kohn-Sham theory can be applied in several distinct ways depending on what is being investigated. In solid state calculations, the local density approximations are still commonly used along with plane wave basis sets, as an electron gas approach is more appropriate for electrons delocalised through an infinite solid. In molecular calculations, however, more sophisticated functionals are needed, and a huge variety of exchange-correlation functionals have been developed for chemical applications. Some of these are inconsistent with the uniform electron gas approximation, however, they must reduce to LDA in the electron gas limit. Among physicists, probably the most widely used functional is the revised Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof exchange model (a direct generalized-gradient parametrization of the free electron gas with no free parameters); however, this is not sufficiently calorimetrically accurate for gas-phase molecular calculations. In the chemistry community, one popular functional is known as BLYP (from the name Becke for the exchange part and Lee, Yang and Parr for the correlation part). Even more widely used is B3LYP which is a hybrid functional in which the exchange energy, in this case from Becke's exchange functional, is combined with the exact energy from Hartree-Fock theory. Along with the component exchange and correlation funсtionals, three parameters define the hybrid functional, specifying how much of the exact exchange is mixed in. The adjustable parameters in hybrid functionals are generally fitted to a 'training set' of molecules. Unfortunately, although the results obtained with these functionals are usually sufficiently accurate for most applications, there is no systematic way of improving them (in contrast to some of the traditional wavefunction-based methods like configuration interaction or coupled cluster theory). Hence in the current DFT approach it is not possible to estimate the error of the calculations without comparing them to other methods or experiments.

For molecular applications, in particular for hybrid functionals, Kohn-Sham DFT methods are usually implemented just like Hartree-Fock itself.

[edit] Thomas-Fermi model

The predecessor to density functional theory was the Thomas-Fermi model, developed by Thomas and Fermi in 1927. They used a statistical model to approximate the distribution of electrons in an atom. The mathematical basis postulated that electrons are distributed uniformly in phase space with two electrons in every h3 of volume[6]. For each element of coordinate space volume d3r we can fill out a sphere of momentum space up to the Fermi momentum pf[7]

Equating the number of electrons in coordinate space to that in phase space gives:

Solving for pf and substituting into the classical kinetic energy formula then leads directly to a kinetic energy represented as a functional of the electron density:

- where

As such, they were able to calculate the energy of an atom using this kinetic energy functional combined with the classical expressions for the nuclear-electron and electron-electron interactions (which can both also be represented in terms of the electron density).

Although this was an important first step, the Thomas-Fermi equation's accuracy is limited because the resulting kinetic energy functional is only approximate, and because the method does not attempt to represent the exchange energy of an atom as a conclusion of the Pauli principle. An exchange energy functional was added by Dirac in 1928.

However, the Thomas-Fermi-Dirac theory remained rather inaccurate for most applications. The largest source of error was in the representation of the kinetic energy, followed by the errors in the exchange energy, and due to the complete neglect of electron correlation.

Teller (1962) showed that Thomas-Fermi theory cannot describe molecular bonding. This can be overcome by improving the kinetic energy functional.

The kinetic energy functional can be improved by adding the Weizsäcker (1935) correction:[8][9]

[edit] Software supporting DFT

DFT is supported by many Quantum chemistry and solid state physics codes, often along with other methods.

[edit] See also

- Basis set (chemistry)

- Gas in a box

- The Helium Atom

- Kohn-Sham equations

- Local density approximation

- Molecule

- Molecular modeling

- Quantum chemistry

- List of quantum chemistry and solid state physics software

- Software for molecular mechanics modeling

- Thomas-Fermi model

[edit] Books on DFT

- R. Dreizler, E. Gross, Density Functional Theory (Plenum Press, New York, 1995).

- C. Fiolhais, F. Nogueira, M. Marques (eds.), A Primer in Density Functional Theory (Springer-Verlag, 2003). [1]

- Kohanoff, J., Electronic Structure Calculations for Solids and Molecules: Theory and Computational Methods (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- W. Koch, M. C. Holthausen, A Chemist's Guide to Density Functional Theory (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, ed. 2, 2002).

- R. G. Parr, W. Yang, Density-Functional Theory of Atoms and Molecules (Oxford University Press, New York, 1989), ISBN 0-19-504279-4, ISBN 0-19-509276-7 (pbk.).

- N.H. March, Electron Density Theory of Atoms and Molecules (Academic Press, 1992), ISBN 0-12-470525-1.

- Richard M. Martin, Electronic Structure: Basic Theory and Practical Methods, Cambridge University Press, 2004

[edit] Key papers

- L.H. Thomas, The calculation of atomic fields, Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc, 23 542-548

- P. Hohenberg and W. Kohn, Phys. Rev. 136 (1964) B864

- W. Kohn and L. J. Sham, Phys. Rev. 140 (1965) A1133

- A. D. Becke, J. Chem. Phys. 98 (1993) 5648

- C. Lee, W. Yang, and R. G. Parr, Phys. Rev. B 37 (1988) 785

- P. J. Stephens, F. J. Devlin, C. F. Chabalowski, and M. J. Frisch, J. Phys. Chem. 98 (1994) 11623

- K. Burke, J. Werschnik, and E. K. U. Gross, Time-dependent density functional theory: Past, present, and future. J. Chem. Phys. 123, 062206 (2005). OAI: arXiv.org:cond-mat/0410362.

[edit] References

- ^ a b Hohenberg, P.; Kohn, W. (1964). "Inhomogeneous electron gas". Phys. Rev. 136 (3B): B864–B871. doi:.

- ^ Levy, Mel (1979). "Universal variational functionals of electron densities, first-order density matrices, and natural spin-orbitals and solution of the v-representability problem". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76 (12): 6062-6065.

- ^ a b Vignale, G.; Rasolt, Mark (1987). "Density-functional theory in strong magnetic fields". Phys. Rev. Lett. (American Physical Society) 59 (20): 2360–2363. doi:.

- ^ Kohn, W.; Sham, L. J. (1965). "Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects". Phys. Rev. 140 (4A): A1133–A1138. doi:.

- ^ John P. Perdew, Adrienn Ruzsinszky, Jianmin Tao, Viktor N. Staroverov, Gustavo Scuseria and Gábor I. Csonka (2005). "Prescriptions for the design and selection of density functional approximations: More constraint satisfaction with fewer fits". J. Chem. Phys. 123: 062201. doi:.

- ^ Parr and Yang 1989, p.47

- ^ March 1992, p.24

- ^ Weizsäcker, C. F. v. (1935). "Zur Theorie der Kernmassen". Zeitschrift für Physik 96 (7-8): 431-58. doi:10.1007/BF01337700.

- ^ Parr and Yang 1989, p.127

[edit] External links

- Walter Kohn, Nobel Laureate Freeview video interview with Walter on his work developing density functional theory by the Vega Science Trust.

- Klaus Capelle, A bird's-eye view of density-functional theory

- Walter Kohn, Nobel Lecture

- Density functional theory on arxiv.org

- FreeScience Library -> Density Functional Theory

- The ABC of DFT

- Density Functional Theory -- an introduction

![\hat H \Psi = \left[{\hat T}+{\hat V}+{\hat U}\right]\Psi = \left[\sum_i^N -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\nabla_i^2 + \sum_i^N V(\vec r_i) + \sum_{i<j}^N U(\vec r_i, \vec r_j)\right] \Psi = E \Psi](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/8/9/8/898fcb5fdcfdd88fc851829a7ac5adc9.png)

![\,\!\Psi_0 = \Psi[n_0]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/2/7/3/27347d299383b927bcef534699fa7035.png)

![O[n_0] = \left\langle \Psi[n_0] \left| \hat O \right| \Psi[n_0] \right\rangle](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/0/a/e/0ae8d09f224aff6ca8582d0345697ad5.png)

![E_0 = E[n_0] = \left\langle \Psi[n_0] \left| \hat T + \hat V + \hat U \right| \Psi[n_0] \right\rangle](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/c/6/4/c6482ef0878d54103ac0f04ede7479a0.png)

![V[n_0] = \int V(\vec r) n_0(\vec r){\rm d}^3r](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/2/a/a/2aaadf01af7e5e4c10929f9518a11ce3.png)

![V[n] = \int V(\vec r) n(\vec r){\rm d}^3r](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/9/5/3/953ee6bdd3fb5b88167aea613e8f16f6.png)

![E[n] = T[n]+ U[n] + \int V(\vec r) n(\vec r){\rm d}^3r](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/a/7/7/a77376c23cf64fcf19999bb0f021d90f.png)

![E_s[n] = \left\langle \Psi_s[n] \left| \hat T_s + \hat V_s \right| \Psi_s[n] \right\rangle](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/7/7/3/77384ef3f9d6d49dff03db06a05dacea.png)

![\left[-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\nabla^2+V_s(\vec r)\right] \phi_i(\vec r) = \epsilon_i \phi_i(\vec r)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/f/b/3/fb393974bd442633dd64993db7ff7c80.png)

![V_s(\vec r) = V(\vec r) + \int \frac{e^2n_s(\vec r\,')}{|\vec r-\vec r\,'|} {\rm d}^3r' + V_{\rm XC}[n_s(\vec r)]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/b/f/2/bf220ad034de0ba662f84d2d106231eb.png)

![E_{\rm XC}[n]=\int\epsilon_{\rm XC}(n)n (\vec{r}) {\rm d}^3r](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/b/5/f/b5f885f07516c2d674f09698be1c55ce.png)

![E_{\rm XC}[n_\uparrow,n_\downarrow]=\int\epsilon_{\rm XC}(n_\uparrow,n_\downarrow)n (\vec{r}){\rm d}^3r](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/6/b/3/6b3268902f7f260906505f419054ab2a.png)

![E_{XC}[n_\uparrow,n_\downarrow]=\int\epsilon_{XC}(n_\uparrow,n_\downarrow,\vec{\nabla}n_\uparrow,\vec{\nabla}n_\downarrow)

n (\vec{r}) {\rm d}^3r](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/6/c/8/6c8281900ff39d1e31cb4446841aa7b4.png)

![t_{TF}[n] = \frac{p^2}{2m_e} \propto \frac{(n^{1/3})^2}{2m_e} \propto n^{2/3}(\vec{r})](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/8/e/7/8e788240c2049033ccc0aefb2a09a6f2.png)

![T_{TF}[n]= C_F \int n(\vec{r}) n^{2/3}(\vec{r}) d^3r =C_F\int n^{5/3}(\vec{r}) d^3r](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/e/a/c/eac88ebfeecc470366ae8b43c18e886a.png)

![T_W[n]=\frac{1}{8}\frac{\hbar^2}{m}\int\frac{|\nabla n(\vec{r})|^2}{n(\vec{r})}dr](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/8/e/b/8eb85fa83eda3ee32c9ba647fef03715.png)