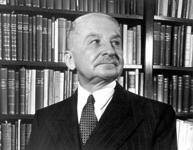

Ludwig von Mises

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Western Economists 20th-Century Economists (Austrian economics) |

|

|

|

| Full name | Ludwig Heinrich Edler von Mises |

|---|---|

| School/tradition | Austrian School |

| Main interests | economics, political economy, philosophy of history, epistemology, rationalism, classical liberalism, Libertarianism |

| Notable ideas | praxeology, economic calculation problem, methodological dualism |

|

Influenced by

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Ludwig Heinrich Edler von Mises (pronounced [ˈluːtvɪç fɔn ˈmiːzəs]) (September 29, 1881 – October 10, 1973) was an Austrian economist, philosopher, author and liberal who had a major influence on the modern libertarian movement.

Contents |

[edit] Biography

[edit] Early life

Ludwig von Mises was born on September 29, 1881, in the city of Lemberg in Galicja, Austro-Hungary (now Lviv, Ukraine), to parents Arthur Edler von Mises from a recently ennobled Jewish family involved in building and financing railroads, and Adele von Mises (née Landau)[1]. Arthur was stationed there as a construction engineer with Czernowitz railroad company. At the age of twelve Ludwig spoke fluent German, Polish, and French, and could understand Ukrainian.[2] Mises had two younger brothers: applied physicist Richard von Mises, and later Karl von Mises, who died in infancy from scarlet fever. When Ludwig and Richard were small children, his family moved back to their ancestral home of Vienna.

In 1900, he attended the University of Vienna, becoming influenced by the works of Carl Menger. Mises' father died in 1903, and in 1906 Mises was awarded his doctorate.

[edit] Professional life

In the years from 1904 to 1914, Mises attended lectures given by the prominent Austrian economist Eugen von Boehm-Bawerk. Mises taught as a Privatdozent at the Vienna University in the years from 1913 to 1934, while formally serving as secretary at the Vienna Chamber of Commerce since 1909, and, according to the Mises Institute, one of the closest economic advisers of Engelbert Dollfuss. [1].

In 1934 Mises left Austria for Geneva, Switzerland, where he was a professor at the Graduate Institute of International Studies until 1940. Fearing the prospect of Germany taking control over Switzerland, in 1940 Mises with other Jewish refugees left Europe and emigrated to New York City[3]. There he became a visiting professor at New York University, from 1945 until his retirement in 1969, though he was not salaried by the university. Instead, he earned his living from funding by businessmen such as Lawrence Fertig. For part of this period, Mises worked on currency issues for the Pan-Europa movement led by a fellow NYU faculty member and Austrian exile, Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi.[4] He received an honorary doctorate from Grove City College.

Despite his growing fame, Mises listed himself plainly in the New York phone directory and welcomed students into his home.[citation needed] He died at the age of 92 at St. Vincent's hospital in New York.

[edit] Contributions to the field of economics

Mises wrote and lectured extensively on behalf of classical liberalism and is seen as one of the leaders of the Austrian School of economics.[citation needed] In his treatise on economics, Human Action, Mises introduced praxeology as a more general conceptual foundation of the social sciences and established that economic laws were only arrived at through the means of methodological individualism firmly rejecting positivism and materialism as a foundation for the social sciences. Many of his works, including Human Action, were on two related economic themes:

- monetary economics and inflation;

- the differences between government controlled economies and free trade.

Mises argued that money is demanded for its usefulness in purchasing other goods, rather than for its own sake and that any unsound credit expansion causes business cycles. His other notable contribution was his argument that socialism must fail economically because of the economic calculation problem – the impossibility of a socialist government being able to make the economic calculations required to organize a complex economy. Mises projected that without a market economy there would be no functional price system, which he held essential for achieving rational allocation of capital goods to their most productive uses. Socialism would fail as demand cannot be known without prices, according to Mises. Mises' criticism of socialist paths of economic development is well-known:

The only certain fact about Russian affairs under the Soviet regime with regard to which all people agree is: that the standard of living of the Russian masses is much lower than that of the masses in the country which is universally considered as the paragon of capitalism, the United States of America. If we were to regard the Soviet regime as an experiment, we would have to say that the experiment has clearly demonstrated the superiority of capitalism and the inferiority of socialism.[5]

These arguments were elaborated on by subsequent Austrian economists such as Friedrich Hayek[6] and students like Hans Sennholz and Murray Rothbard.

In Interventionism, An Economic Analysis (1940), Ludwig von Mises wrote:

The usual terminology of political language is stupid. What is 'left' and what is 'right'? Why should Hitler be 'right' and Stalin, his temporary friend, be 'left'? Who is 'reactionary' and who is 'progressive'? Reaction against an unwise policy is not to be condemned. And progress towards chaos is not to be commended. Nothing should find acceptance just because it is new, radical, and fashionable. 'Orthodoxy' is not an evil if the doctrine on which the 'orthodox' stand is sound. Who is anti-labor, those who want to lower labor to the Russian level, or those who want for labor the capitalistic standard of the United States? Who is 'nationalist,' those who want to bring their nation under the heel of the Nazis, or those who want to preserve its independence?

Robert Heilbroner acknowledged after the fall of the Soviet Union, that "It turns out, of course, that Mises was right" about the impossibility of socialism. "Capitalism has been as unmistakable a success as socialism has been a failure. Here is the part that's hard to swallow. It has been the Friedmans, Hayeks, and von Miseses who have maintained that capitalism would flourish and that socialism would develop incurable ailments." [7]

[edit] Criticism

In a 1957 review of his book, The Anti-Capitalistic Mentality, The Economist said of von Mises: "Profesor von Mises has a splendid analytical mind and an admirable passion for liberty ; but as a student of human nature he is worse than null and as a debater he is of Hyde Park standard."[8]

In a 1978 interview Friedrich Hayek said of his book Socialism: "At first we all felt he was frightfully exaggerating and even offensive in tone. You see, he hurt all our deepest feelings, but gradually he won us around, although for a long time I had to -- I just learned he was usually right in his conclusions, but I was not completely satisfied with his argument." [9]

[edit] Bibliography

- The Development of the Relationship Between Peasant and Lord of the Manor in Galicia, 1772-1848 (1902, never translated into English)

- The Theory of Money and Credit (1912, enlarged US edition 1953)

- Nation, State, and Economy (1919)

- Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis (online version) (1922, 1932, 1951)

- Liberalism (1927, 1962)

- Critique of Interventionism (1929)

- Epistemological Problems of Economics (1933, 1960)

- Omnipotent Government: The Rise of Total State and Total War (1944) Preview

- Bureaucracy (1944)

- Planned Chaos (1947, added to 1951 edition of Socialism)

- Human Action: A Treatise on Economics (1949, 1963, 1966, 1996)

- preceded by Nationalökonomie in 1940

- Planning for Freedom (1952, enlarged editions in 1962, 1974, and 1980)

- The Anti-Capitalistic Mentality (1956)

- Theory and History: An Interpretation of Social and Economic Evolution (1957)

- The Ultimate Foundation of Economic Science (1962)

- Notes and Recollections (1978)

- Economic Policy: Thoughts for Today and Tomorrow (1979, lectures given in 1959)

- Interventionism: An Economic Analysis (1998)

|

|||||

[edit] See also

- Analytic-synthetic distinction and Ludwig von Mises' response to the Kantian challenge

- Contributions to liberal theory

- Liberalism in Austria

- Libertarianism

- List of Austrian scientists

- List of Austrians

- Mont Pelerin Society

- Karl Polanyi - with whom von Mises debated leading to Polanyi's book The Great Transformation

[edit] Further reading

- Brian Doherty. Radicals for Capitalism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern American Libertarian Movement (2007)

- Jörg Guido Hülsmann. Mises: The Last Knight of Liberalism (Auburn, Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2007), xvi+1143 pages, ISBN 978-1-933550-18-3. Also available as a PDF file.

- Ron Paul. "Mises and Austrian economics: A personal view" The Ludwig von Mises Institute of Auburn University (1984), 31 pages.

- Murray N. Rothbard (1987). "Mises. Ludwig Edler von," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, pp. 479-80.

[edit] Notes

- Note regarding personal names: Edler is a title, (<G, meaning 'noble'), in rank similar to that of a baronet, not a first or middle name. The female form is Edle. Similarly, below, Ritter is German for 'knight'; Graf is German for 'count'.

- ^ Hulsmann, Jorg Guido (2007). Mises: The Last Knight of Liberalism. Ludwig von Mises Institute.

- ^ Erik Ritter von Kuehnelt-Leddihn "The Cultural Background of Ludwig von Mises", The Ludwig von Mises Institute, page 1

- ^ Hulsmann, Jorg Guido (2007). Mises: The Last Knight of Liberalism. Ludwig von Mises Institute. p. xi.

- ^ Coudenhove-Kalergi, Richard Nikolaus, Graf von (1953). An idea conquers the world. London: Hutchinson. p. 247.

- ^ Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis by Ludwig von Mises.

- ^ F. A. Hayek, (1935), "The Nature and History of the Problem" and "The Present State of the Debate," in F. A. Hayek, ed. Collectivist Economic Planning, pp. 1-40, 201-43.

- ^ "The Man Who Told the Truth", Reason, 1990. Retrieved on April 4 2009.

- ^ "Liberalism in Caricature", The Economist

- ^ UCLA Oral History "interview with Friedrich Hayek", American Libraries/Internet Archive, 1978. Retrieved on April 4 2009 (source with quotes).

[edit] External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Ludwig von Mises |

- The Complete Mises Bibliography from the Ludwig von Mises Institute

- Biography from the Ludwig von Mises Institute

- Ludwig von Mises at the Open Directory Project

- Biblioteca Ludwig von Mises

- Mises on Keynes 1927 review by Mises on a lecture given by Keynes in Berlin

- Ludwig von Mises Institute

- Bio by Mises scholar Jörg Guido Hülsmann

- Scholar, Creator, Hero – Rothbard on Mises

- mises.de: Books and Articles in the original German versions by Ludwig von Mises and other Authors of the Austrian School

[edit] Online e-books

- The Free Market and Its Enemies: Pseudo-Science, Socialism, and Inflation Lecture Series, Volume 1, with an introduction by Richard Ebeling. Copyright 2004 Foundation for Economic Education. All rights reserved.

- Nine Books by Mises, made available online by the Liberty Fund, publishers of the Complete Works of Ludwig von Mises

- Human Action: A treatise on economics 1949 (4th edition, 1996). San Francisco: Fox & Wilkes. ISBN 0-930073-18-5. Made available online by The Ludwig von Mises Institute.

- Human Action: The Scholars Edition Auburn, Alabama: Mises Institute, 1999. Re-issue of the classic 1949 Edition with new introduction and expanded index.

- A Critique of Interventionism, The Ludwig von Mises Institute.

- The Anti-Capitalistic Mentality, Libertarian Press 1990.

- McCaine, Catamite. Von Mises, The Austrian School, and Class Struggle. Holland Revolutionary Press

- Economic Freedom and Interventionism, The Ludwig von Mises Institute.

- Economic Policy: Thoughts for Today and Tomorrow Second Edition, with a New Introduction by Bettina Bien Greaves, The Ludwig von Mises Institute.

- The Historical Setting of the Austrian School of Economics, The Ludwig von Mises Institute.

- Liberalism: In the Classical Tradition, English edition Copyright 1985 The Foundation for Economic Education, Irvington, NY. Translation by Ralph Raico. Online edition Copyright The Mises Institute, 2000.

- The Theory of Money and Credit. 1912 integration of microeconomics and macroeconomics. ISBN 0-913966-71-1. Online edition Copyright The Mises Institute.

- Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis Von Mises' critique of Socialism

- Theory and History. 1957 treatise on social and economic evolution, with a preface by Murray N. Rothbard. Online edition Copyright The Mises Institute, 2000.

- My Years With Ludwig von Mises by Margit von Mises. 1976. Memoir of their life together.

|

|||||||||||||||||