Oedipus the King

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Oedipus the King | |

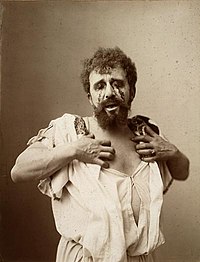

Albert Greiner as Oedipus in 1896. |

|

| Written by | Sophocles |

|---|---|

| Chorus | Theban Elders |

| Characters | Oedipus Priest Creon Tiresias Jocasta Messenger Shepherd Second Messenger |

| Mute | Daughters of Oedipus (Antigone and Ismene) |

| Date premiered | c. 429 BCE |

| Place premiered | Theatre of Dionysos, Athens |

| Original language | Classical Greek |

| Subject | Episode from Mythological story of Oedipus |

| Genre | Athenian tragedy |

| Setting | Thebes |

Oedipus the King (Greek Οιδίπους Τύραννος, Latin: Oedipus Rex) is an Athenian tragedy by Sophocles that was first performed c. 429 BCE.[1] It was the second of Sophocles' three Theban plays to be produced, but it comes first in the internal chronology, followed by Oedipus at Colonus and then Antigone. Over the centuries, it has come to be regarded by many as the Greek tragedy par excellence.[2]

Contents |

[edit] Plot

[edit] Background

Much of the myth of Oedipus takes place before the opening scene of the play. The protagonist of the tragedy is the son of King Laius and Queen Jocasta of Thebes. After Laius learns from an oracle that "he is doomed/To perish by the hand of his own son," he binds tightly together with a pin the feet of the infant Oedipus and orders Jocasta to kill the infant. Hesitant to do so, she demands a servant to commit the act for her. Instead, the servant abandons the baby in the fields, leaving the baby's fate to the gods. A shepherd rescues the infant and names him Oedipus (or "swollen foot"). Intending to raise the baby himself, but not possessing of the means to do so, the shepherd gives it to a fellow shepherd from a distant land, who spends the summers sharing pastureland with his flocks.The second shepherd carries the baby with him to Corinth, where Oedipus is taken in and raised in the court of the childless King Polybus of Corinth as if he were his own.

As a young man in Corinth, Oedipus hears a rumour that he is not the biological son of Polybus and his wife Merope. When Oedipus sounds them out on this, they deny it, but, still suspicious, he asks the Delphic Oracle who his parents really are. The Oracle seems to ignore this question, telling him instead that he is destined to "Mate with [his] own mother, and shed/With [his] own hands the blood of [his] own sire." Desperate to avoid his foretold fate, Oedipus leaves Corinth in the belief that Polybus and Merope are indeed his true parents and that, once away from them, he will never harm them.

On the road to Thebes, he meets Laius, his true father. Unaware of each other's identities, they quarrel over whose chariot has right-of-way. Oedipus's pride leads him to murder Laius, fulfilling part of the oracle's prophecy. Shortly after, he solves the riddle of the Sphinx, which has baffled many a diviner: "What is the creature that walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at noon, and three in the evening?"

To this Oedipus replies, "Man" (who crawls on all fours as an infant, walks upright later, and needs a walking stick in old age), and the distraught Sphinx throws herself off the cliffside. Oedipus's reward for freeing the kingdom of Thebes from her curse is the kingship and the hand of queen Jocasta, his biological mother. The prophecy is thus fulfilled, although none of the main characters know it.

[edit] The Action of the Play

A priest and the chorus of Thebans arrive at the palace to call upon their King, Oedipus, to aid them with the plague of Apollo ravaging the city. Oedipus has sent his brother-in-law Creon to ask help of Delphi, who at that moment returns. Creon says the plague is the result of religious pollution, caused because the murderer of their former King, Laius, was never caught. Oedipus vows to find the murderer and curses him for the plague that he has caused.

Oedipus summons the blind prophet Tiresias for help. When Tiresias arrives he claims to know the answers to Oedipus' questions, but refuses to speak, instead telling Oedipus to abandon his search. Oedipus is enraged by Tiresias' refusal, and says the prophet must be complicit in the murder. Outraged, Tiresias tells the king that Oedipus himself is the murderer. Oedipus cannot see how this could be, and concludes that the prophet must have been paid off by Creon in an attempt to undermine him. The two argue vehemently and eventually Tiresias leaves, muttering darkly that when the murderer is discovered he shall be: a native citizen of Thebes; brother and father to his own children; and son and husband to his own mother.

Creon arrives to face Oedipus' accusations. The King demands that Creon be executed, however the chorus convince him to let Creon live. Oedipus' wife Jocasta enters, and attempts to comfort Oedipus, telling him he should take no notice of prophets. Many years ago she and Laius received an oracle which never came true. It was said that Laius would be killed by his own son, but, as all Thebes knows, Laius was killed by bandits at a crossroads on the way to Delphi.

The mention of this crossroads causes Oedipus to pause and ask for more details. He asks Jocasta what Laius looked like, and suddenly becomes worried that Tiresias' accusations were true. Oedipus sends for the one surviving witness of the attack to be brought to the palace from the fields where he now works as a shepherd. Jocasta, confused, asks Oedipus what is the matter, and he tells her.

Many years ago, at a banquet in Corinth, a man drunkenly accused Oedipus of not being his father's son. Bothered by the comment Oedipus went to Delphi and asked the oracle about his parentage. Instead of answers he was given a prophesy that he would one day murder his father and sleep with his mother. Upon hearing this he resolved to quit Corinth and never return. While travelling he came to the very crossroads where Laius was killed, and encountered a carriage which attempted to drive him off the road. An argument ensued and Oedipus killed the travellers, including a man who matches Jocasta's description of Laius.

Oedipus has hope, however, because the story is that Laius was murdered by a gang of robbers. If the shepherd confirms that Laius was attacked by many men, then Oedipus is in the clear.

A man arrives from Corinth with the message that Oedipus' father has died. Oedipus, to the surprise of the messenger, is made ecstatic by this news, for it proves one half of the prophesy false, for now he can never kill his father. However he still fears that he may somehow commit incest with his mother. The messenger, eager to ease Oedipus' mind, tells him not to worry, because Merope the Queen of Corinth was not in fact his real mother.

It emerges that this messenger was formerly a shepherd on Mount Cithaeron, and that he was given a baby, which the childless Polybus then adopted. The baby, he says, was given to him by another shepherd from the household Laius, who had been told to get rid of the child. Oedipus asks the chorus if anyone knows who this man was, or where he might be now. They respond that he is the same shepherd who was witness to the murder of Laius, and who Oedipus had already been sent for. Jocasta, who has by now realised the truth, desperately begs Oedipus to stop asking questions, but he refuses and Jocasta runs into the palace.

When the shepherd arrives Oedipus questions him, but he begs to be allowed to leave without answering further. Oedipus presses him however, finally threatening him with torture or execution. It emerges that the child he gave away was Laius' own son, and that Jocasta had given the baby to the shepherd to secretly be exposed upon the mountainside. This was done in fear of the prophecy that Jocasta said had never come true: that the child would kill its father.

Everything has at last been revealed, and Oedipus curses himself and fate before leaving the stage. The chorus laments how even a great man can be felled by fate, and shortly afterwards a servant exits the palace to speak of what has happened inside. When Jocasta entered the house she ran to the palace bedroom and hanged herself there. Shortly afterwards Oedipus entered in a fury, calling on his servants to bring him a sword so that he might kill himself. He then raged through the house until he came upon Jocasta's body. Giving a cry, Oedipus took her down and removed the long gold pins that held her dress together, before plunging them into his own eyes in despair.

A blind Oedipus now exits the palace and begs to be exiled as soon as possible. Creon enters, saying that Oedipus shall be taken into the house until oracles can be consulted regarding what it best to be done. Oedipus' two daughters, Antigone and Ismene, are sent out and Oedipus laments that they should be born to such a cursed family. He asks Creon to watch over them and Creon agrees, before sending Oedipus back into the palace.

On an empty stage the chorus repeat the common Greek maxim, that no man should be considered fortunate until he is dead[3].

[edit] Relationship with the mythic tradition

The two cities of Troy and Thebes, were the major focus of Greek epic poetry. The events surrounding the Trojan War were chronicled in the Epic Cycle, of which much remains, and those about Thebes in the Theban Cycle, which have been lost. The Theban Cycle recounted the sequence of tragedies that befell the house of Laius, of which the story of Oedipus is a part.

In Homer's Odyssey (XI.271ff.) we get our earliest account of the Oedipus myth when Odysseus encounters Jocasta (named Epicaste) in the underworld. Homer briefly summarises the story of Oedipus, including the incest, patricide, and Jocasta's subsequent suicide. However in the Homeric version Oedipus remains King of Thebes after the revelation and neither blinds himself, nor is sent into exile. In particular, it is said that the gods made the matter known, whilst in Oedipus the King Oedipus very much discovers the truth himself[4].

In 467 BC, Sophocles' fellow tragedian Aeschylus won first prize at the City Dionysia with a trilogy about the House of Laius, comprising Laius, Oedipus and Seven against Thebes (the only play which survives). The major difference that we can see between the two tragedians' interpretations, is that the Aeschylean prophecies were conditional, whereas Sophocles' were definite (see discussion on fate below). On other particulars of the myth the two interpretations appear to concur.

[edit] Themes and motifs

[edit] Fate and free will

Fate is a theme that often occurs in Greek writing, tragedies in particular. The inevitability of oracular predictions is one such example: It is predicted that Oedipus shall "kill his father and mate with his mother", thus his parents order a servant to kill the child. As a result Oedipus ends up being adopted and not knowing his true parents. When he then hears the prophecy for himself, he leaves Corinth to avoid this, but in fact runs away from the wrong people. In running away he crosses paths with his biological family, something which otherwise would never have occurred. The idea that attempting to avoid an oracle is the very thing which brings it about is a common motif in many Greek myths, and similarities to Oedipus can for example be seen in the myth of the birth of Perseus.

Two oracles in particular dominate the plot of Oedipus the King. In lines 713 to 714, Jocasta relates the prophecy that was told to Laius before the birth of Oedipus. Namely:

that it was fate that he should die a victim

at the hands of his own son, a son to be born

of Laius and me.

The oracle told to Laius tells only of the patricide, whereas the incest is missing. This perhaps prevents Jocasta and Oedipus from being suspicious of the fact that both had received near-identical oracles. As Oedipus, prompted by Jocasta's recollection, narrates the prophecy which caused him to leave Corinth (791-93):

it was my fate to defile my mother's bed,

to bring forth to men a human family that people could not bear to look upon,

to murder the father who engendered me.

These two oracles are interestingly distinct from the Aeschylean interpretation of the myth. The oracle as told in The Seven Against Thebes is conditional: if Laius has a child, then he shall grow up to kill his father. Thus, rather like his Oresteia, Aeschylus' interpretation of the myth is one of a curse running through successive generations of a family begun by a single choice[5]. Sophocles' Oedipus, however, is simply doomed from his moment of birth, and thus there is no justification for the punishment that he receives. This is what the chorus refers to (1186-1222) when they mourn the fact that even the best men can be destroyed by fate.

Given our modern conception of fate and fatalism, readers of the play have a tendency to view Oedipus as a mere puppet controlled by greater forces, a man crushed by the gods and fate for no good reason. This, however, is not an entirely accurate reading. While it is a mythological truism that oracles exist to be fulfilled, oracles merely predict the future. Neither they nor Fate dictates the future. In his landmark essay "On Misunderstanding the Oedipus Rex",[6] E.R. Dodds draws a comparison with Jesus's prophecy at the Last Supper that Peter would deny him three times. Jesus knows that Peter will do this, but we as readers would in no way suggest that Peter was a puppet of fate being forced to deny Christ. Free will and predestination are by no means mutually exclusive, and thus is the case with Oedipus.

The oracle delivered to Oedipus is often called a "self-fulfilling prophecy", in that the prophecy itself sets in motion events that conclude with its own fulfillment.[7] This, however, is not to say that Oedipus is a victim of fate and has no free will. The oracle inspires a series of specific choices, freely made by Oedipus, which lead to kill his father and marry his mother. Oedipus chooses not to return to Corinth after hearing the oracle, just as he chooses to head toward Thebes, to kill Laius, to marry and to take Jocasta specifically as his bride; in response to the plague at Thebes, he chooses to send Creon to the Oracle for advice and then to follow that advice, initiating the investigation into Laius's murder. None of these choices is predetermined.

Another characteristic of oracles in myth is that they are almost always misunderstood by those who hear them; hence Oedipus's misunderstanding the significance of the Delphic Oracle. He visits Delphi to find out who his real parents are and assumes that the Oracle refuses to answer that question, offering instead an unrelated prophecy which forecasts patricide and incest. Oedipus's assumption is incorrect: the Oracle does answer his question. Stated less elliptically, the answer to his question reads thus: "Polybus and Merope are not your parents. You will one day kill a man who will turn out to be your biological father. You will also one day marry, and the woman whom you choose as your bride will be your mother."[citation needed]

[edit] State control

The exploration of this theme in Oedipus the King is paralleled by the examination of the conflict between the individual and the state in Antigone. The dilemma that Oedipus faces here is similar to that of the tyrannical Creon: each man has, as king, made a decision that his subjects question or disobey; each king also misconstrues both his own role as a sovereign and the role of the rebel. When informed by the blind prophet Tiresias that religious forces are against him, each king claims that the priest has been corrupted. It is here, however, that their similarities come to an end: while Creon, seeing the havoc he has wreaked, tries to amend his mistakes, Oedipus refuses to listen to anyone.[8]

[edit] Sight and blindness

Literal and metaphorical references to eyesight appear throughout Oedipus the King. Clear vision serves as a metaphor for insight and knowledge, but the clear-eyed Oedipus is blind to the truth about his origins and inadvertent crimes. The prophet Tiresias, on the other hand, although literally blind, "sees" the truth and relays what is revealed to him. Only after Oedipus has physically blinded himself so as not to look upon his children, the fruit of his unconscious sin, does he gain a limited prophetic ability, as seen in Oedipus at Colonus.[original research?]. It is deliberately ironic that the "seer" can "see" better than Oedipus, despite being blind. In one line (Oedipus Rex, 469), Tiresias says:

"So, you mock my blindness? Let me tell you this. You [Oedipus] with your precious eyes, you're blind to the corruption of your life..."

(Robert Fagles 1984)

[edit] See also

- Oedipus

- Oedipus rex, an opera by Igor Stravinsky

- Oedipus Rex, a film by Pier Paolo Pasolini

- Œdipe, an opera by Georges Enescu

- Oedipus Tex

- Oedipus complex

[edit] Notes

- ^ Although we know that Sophocles won second prize with the group of plays that included Oedipus the King, its date of production is uncertain. The prominence of the Theban plague at the play's opening suggests to many scholars a reference to the plague that devastated Athens in 430 BCE, and hence a production date shortly thereafter. See, for example, Bernard Knox: "The Date of the Oedipus Tyrannus of Sophocles," The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 77, No. 2 (1956), 133-147.

- ^ It is widely argued that Aristotle in his Poetics identifies Oedipus the King as the best Greek tragedy. See, for example, Elizabeth Belfiore: Tragic Pleasures: Aristotle on Plot and Emotion (Princeton, 1992), p. 176. Nevertheless, although Aristotle praises many aspects of the play, he also expresses a preference (1454a) for tragedies in which a timely recognition prevents violence and a plot arc that moves from misfortune to good fortune (as in Euripides's Iphigeneia at Tauris); Oedipus the King, conversely, features a belated recognition of mistaken violence, and a plot that moves from good fortune to misfortune. See Christopher S. Morrissey, "Oedipus the Cliché: Aristotle on Tragic Form and Content", Anthropoetics 9, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 2003).

- ^ Herodotus, in his Histories (Book 1.32), attributes this maxim to the 6th-century Athenian statesman Solon.

- ^ Dawe, R.D. ed. 2006 Sophocles: Oedipus Rex, revised edition. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. p.1

- ^ Greece & Rome, 2nd Ser., Vol. 13, No. 1 (Apr., 1966), pp. 37-49

- ^ Greece & Rome, 2nd Ser., Vol. 13, No. 1 (Apr., 1966), pp. 37-49

- ^ Strictly speaking, this is inaccurate: Oedipus himself set these events in motion when he decided to investigate his parentage against the advice of Polybus and Merope.

- ^ Sophocles. Sophocles I: Oedipus the King, Oedipus at Colonus, Antigone. 2nd ed. Grene, David and Lattimore, Richard, eds. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1991.[clarification needed]

[edit] Translations

- Thomas Francklin, 1759 - verse

- Edward H. Plumptre, 1865 - verse: full text

- Richard C. Jebb, 1904 - prose: full text

- Francis Storr, 1912 - verse: full text

- William Butler Yeats, 1928 - mixed prose and verse

- David Grene, 1942 (revised ed. 1991) - verse

- E.F. Watling, 1947

- Dudley Fitts and Robert Fitzgerald, 1949 - verse

- Theodore Howard Banks, 1956 - verse

- Albert Cook, 1957 - verse

- Paul Roche, 1958 - verse

- Bernard Knox, 1959 - prose

- H. D. F. Kitto, 1962 - verse

- Stephen Berg and Diskin Clay - verse

- Robert Bagg, 1982 (revised ed. 2004) - verse

- Robert Fagles, 1984 - verse

- Nick Bartel, 1999 - verse: abridged text

- George Theodoridis, 2005 - prose, full text: [1]

- Luci Berkowitz and Theodore F. Brunner, 1970 - prose

- Ian Johnston, 2004 - verse: full text.

[edit] Additional references

- Brunner, M. "King Oedipus Retried" Rosenberger & Krausz, London, 2000

- Foster, C. Thomas. "How to Read Literature Like a Professor" HarperCollins, New York, 2003

[edit] External links

- Aristotle's Poetics: Notes on Sophocles' Oedipus

- Background on Drama, Generally, and Applications to Sophocles' Play

- Study Guide for Sophocles' Oedipus the King

- Full text English translation of Oedipus the King by Ian Johnston, in verse

- Oedipus the King Book Notes from Literapedia

|

|||||||