Indigenous Australians

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Australian Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

, ,  , ,  , ,  , ,  |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Albert Namatjira, Ernie Dingo, David Gulpilil, Johnathan Thurston, Adam Goodes, Cathy Freeman |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

517,000 (2006)[1] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Several hundred Indigenous Australian languages (many extinct or nearly so), Australian English, Australian Aboriginal English, Torres Strait Creole, Kriol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Majority Christian religions with minority following traditional Dreamtime beliefs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| see List of Indigenous Australian group names |

Indigenous Australians are of the Australian continent and its nearby islands and their descendants.[2] Indigenous Australians are distinguished as either Aboriginal people or Torres Strait Islanders, who currently together make up about 2.6% of Australia's population.

The Torres Strait Islanders are indigenous to the Torres Strait Islands which are at the northern-most tip of Queensland near New Guinea. The term "Aboriginal" has traditionally been applied to indigenous inhabitants of mainland Australia, Tasmania, and some of the other adjacent islands. The use of the term is becoming less common, with names preferred by the various groups becoming more common.

The earliest evidence of human habitation found to date are that of Mungo Man which have been dated at about 40,000 years old, but the time of arrival of the ancestors of Indigenous Australians is a matter of debate among researchers, with estimates ranging as high as 125,000 years ago.[3]

There is great diversity between different Indigenous communities and societies in Australia, each with its own unique mixture of cultures, customs and languages. In present day Australia these groups are further divided into local communities.[4]

Although there were over 250-300 spoken languages with 600 dialects at the start of European settlement, fewer than 200 of these remain in use[5] – and all but 20 are considered to be endangered.[6] The population of Indigenous Australians at the time of permanent European settlement has been estimated at between 318,000 and 750,000,[7] with the distribution being similar to that of the current Australian population, with the majority living in the south-east, centred along the Murray River.[8]

Contents |

[edit] Terminology

[edit] Indigenous Australians

Though Indigenous Australians are seen as being broadly related, there are significant differences in social, cultural and linguistic customs between the various Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups.

[edit] Aboriginal Australians

In the past the word Aboriginal has been used in Australia to describe its Indigenous peoples as early as 1789. It soon became capitalised and employed as the common name to refer to all Indigenous Australians. At present the term refers only to those peoples who were traditionally hunter gatherers. It does not encompass those Indigenous peoples from the Torres Strait who traditionally practised agriculture.

The word Aboriginal has been in use in English since at least the 17th century to mean "first or earliest known, indigenous," (Latin Aborigines, from ab: from, and origo: origin, beginning),[9] Strictly speaking, "Aborigine" is the noun and "Aboriginal" the adjectival form; however the latter is often also employed to stand as a noun.

The use of "Aborigine(s)" or "Aboriginal(s)" in this sense, i.e. as a noun, has acquired negative, even derogatory connotations in some sectors of the community, who regard it as insensitive, and even offensive.[10] The more acceptable and correct expression is "Aboriginal Australians" or "Aboriginal people," though even this is sometimes regarded as an expression to be avoided because of its historical associations with colonialism. "Indigenous Australians" has found increasing acceptance, particularly since the 1980s.[11]

The broad term Aboriginal Australians includes many regional groups that often identify under names from local Indigenous languages. These include:

- Koori (or Koorie) in New South Wales and Victoria (Victorian Aborigines)

- Ngunnawal in the Australian Capital Territory and surrounding areas of New South Wales

- Murri in Queensland

- Noongar in southern Western Australia

- Yamatji in central Western Australia

- Wangkai in the Western Australian Goldfields

- Nunga in southern South Australia

- Anangu in northern South Australia, and neighbouring parts of Western Australia and Northern Territory

- Yapa in western central Northern Territory

- Yolngu in eastern Arnhem Land (NT)

- Tiwi on Tiwi Islands off Arnhem Land. They number around 2,500.

- Anindilyakwa on Groote Eylandt off Arnhem Land

- Palawah (or Pallawah) in Tasmania.[6]

These larger groups may be further subdivided; for example, Anangu (meaning a person from Australia's central desert region) recognises localised subdivisions such as Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara, Ngaanyatjarra, Luritja and Antikirinya.[6] It is estimated that prior to the arrival of British settlers, the population of Indigenous Australians was approximately 318,000–750,000 across the continent.[7]

[edit] Torres Strait Islanders

The Torres Strait Islanders possess a heritage and cultural history distinct from Aboriginal traditions. The eastern Torres Strait Islanders in particular are related to the Papuan peoples of New Guinea, and speak a Papuan language[8]. Accordingly, they are not generally included under the designation "Aboriginal Australians." This has been another factor in the promotion of the more inclusive term "Indigenous Australians". Six percent of Indigenous Australians identify themselves fully as Torres Strait Islanders. A further 4% of Indigenous Australians identify themselves as having both Torres Strait Islanders and Aboriginal heritage.[12]

The Torres Strait Islands comprise over 100 islands[13] which were annexed by Queensland in 1879.[13] Many Indigenous organisations incorporate the phrase "Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander" to highlight the distinctiveness and importance of Torres Strait Islanders in Australia's Indigenous population.

Eddie Mabo was from Mer or Murray Island in the Torres Strait, which the famous Mabo decision of 1992 involved.[13]

[edit] Black

The term "blacks" has often been applied to Indigenous Australians. This owes more to superficial physiognomy than ethnology, as it categorises Indigenous Australians with the other, unrelated black peoples of Asia and Africa. In the 1970s, many Aboriginal activists, such as Gary Foley proudly embraced the term "black", and writer Kevin Gilbert's ground-breaking book from the time was entitled Living Black.

In recent years young Indigenous Australians – particularly in urban areas – have increasingly adopted aspects of Black American and Afro-Caribbean culture, creating what has been described as a form of "black transnationalism." [14]

[edit] Languages

The Indigenous languages of mainland Australia and Tasmania have not been shown to be related to any languages outside Australia. In the late 18th century, there were anywhere between 350 and 750 distinct groupings and a similar number of languages and dialects. At the start of the 21st century, fewer than 200 Indigenous Australian languages remain in use and all but about 20 of these are highly endangered.

Linguists classify mainland Australian languages into two distinct groups: the Pama-Nyungan languages and the non-Pama Nyungan. The Pama-Nyungan languages comprise the majority, covering most of Australia, and are a family of related languages. In the north, stretching from the Western Kimberley to the Gulf of Carpentaria, are found a number of groups of languages which have not been shown to be related to the Pama-Nyungan family or to each other; these are known as the non-Pama-Nyungan languages.

While it has sometimes proven difficult to work out familial relationships within the Pama-Nyungan language family, many Australianist linguists feel there has been substantial success.[15] Against this some linguists, such as R. M. W. Dixon, suggest that the Pama-Nyungan group – and indeed the entire Australian linguistic area – is rather a sprachbund, or group of languages having very long and intimate contact, rather than a genetic linguistic phylum.[16]

It has been suggested that, given their long presence in Australia, Aboriginal languages form one specific sub-grouping. Certainly, similarities in the phoneme set of Aboriginal languages throughout the continent suggest a common origin. One similarity of many Australian languages is that they display mother-in-law languages: special speech registers used in the presence of only certain close relatives. The position of Tasmanian languages is unknown, and it is also unknown whether they comprised one or more than one specific language family.

[edit] History

The consensus among scholars for the arrival of humans in Australia is placed at 40,000 to 50,000 years ago, with a possible range of up to 70,000 years ago. The earliest human remains found to date are that of Mungo Man which have been dated at about 40,000 years old.

Aborigines lived as Hunter-gatherers. They hunted and foraged for food from the land. Aboriginal society was relatively mobile, or semi-nomadic, moving due to the changing food availability found across different areas as seasons changed.

It has been estimated that at the time of first European contact, the absolute minimum pre-1788 population was 315,000, while recent archaeological finds suggest that a population of 750,000 could have been sustained.[7]

The population was split into 250 individual nations, many of which were in alliance with one another, and within each nation there existed several clans, from as little as 5 or 6 to as many as 30 or 40. Each nation had its own language and a few had several. Thus over 250 languages existed, around 200 of which are now extinct or on the verge of extinction.

The mode of life and material cultures varied greatly from region to region. The greatest population density was to be found in the southern and eastern regions of the continent, the River Murray valley in particular.

[edit] Post-European settlement

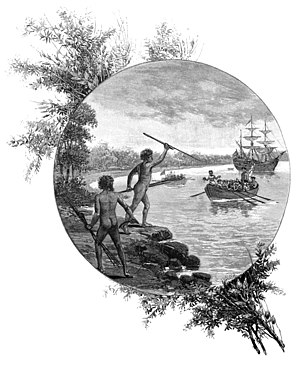

British colonisation of Australia began with the arrival of the First Fleet in Botany Bay in 1788. An immediate consequence of colonisation was a pandemic of Old World diseases, including smallpox which is estimated to have killed up to 90% of the local Darug people within the first three years of white settlement.[17]

Smallpox would kill around 50% of Australia's Indigenous population in the early years of British colonisation.[18]

A second consequence of British settlement was appropriation of land and water resources, which continued throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries as rural lands were converted for sheep and cattle grazing. By 1900 the recorded Indigenous population of Australia had declined to approximately 93,000.[19]

Commonwealth legislation in 1962 specifically gave Aborigines the right to vote in Commonwealth elections. The 1967 referendum allowed the Commonwealth to make laws with respect to Aboriginal people, and for Aboriginal people to be included when the country does a count to determine electoral representation.

In the controversial 1971 Gove land rights case, Justice Blackburn ruled that Australia had been terra nullius before British settlement, and that no concept of native title existed in Australian law. In 1972, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was established on the steps of Parliament House in Canberra. In 1992, the High Court of Australia handed down its decision in the Mabo Case, declaring the previous legal concept of terra nullius to be invalid.

In 2000, Aboriginal sprinter Cathy Freeman lit the Olympic flame at the opening ceremony of the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney.

In 2004, the Australian Government abolished the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), which had been Australia's peak Indigenous organisation. The abolition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission occurred soon after rape allegations were brought against its chairman Geoff Clark.

On 13 February 2008, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd issued a public apology to members of the Stolen Generation on behalf of the Australian Government.

[edit] Culture

There are a large number of tribal divisions and language groups in Aboriginal Australia, and, correspondingly, a wide variety of diversity exists within cultural practices. However, there are some similarities between cultures.

[edit] Belief systems

Religious demography among Indigenous Australians is not conclusive because the methodology of the census is not always well-suited to obtaining accurate information on Aboriginal people.[20] The 1996 census reported that almost 72 percent of Aborigines practised some form of Christianity; 16 percent listed no religion. The 2001 census contained no comparable updated data.[21] There has also been an increase in the number of followers of Islam among the Indigenous Australian community.[22] This growing community includes high-profile members such as the boxer, Anthony Mundine.[23]

In traditional Aboriginal belief systems, a creative epoch known as the Dreamtime stretches back into a remote era in history when the creator ancestors known as the First Peoples traveled across the land, creating and naming as they went.[24] Indigenous Australia's oral tradition and religious values are based upon reverence for the land and a belief in this Dreamtime. The Dreaming is at once both the ancient time of creation and the present-day reality of Dreaming. There were a great many different groups, each with its own individual culture, belief structure, and language. These cultures overlapped to a greater or lesser extent, and evolved over time. Major ancestral spirits include the Rainbow Serpent, Baiame, and Bunjil.

[edit] Music

The various Indigenous Australian communities developed unique musical instruments and folk styles. The didgeridoo, which is widely thought to be a stereotypical instrument of Aboriginal people, was traditionally played by people of only the eastern Kimberley region and Arnhem Land (such as the Yolngu), and then by only the men.[25] Clapping sticks are probably the more ubiquitous musical instrument, especially because they help maintain rhythm for songs.

Contemporary Australian aboriginal music is predominantly of the country music genre. Most Indigenous radio stations – particularly in metropolitan areas – serve a double purpose as the local country-music station. More recently, Indigenous Australian musicians have branched into rock and roll, hip hop and reggae. One of the most well known modern bands is Yothu Yindi playing in a style which has been called Aboriginal rock.

Amongst young Australian aborigines, African-American and Aboriginal hip hop music and clothing is popular. [26] Aboriginal boxing champion and former rugby league player Anthony Mundine identified US rapper Tupac Shakur as a personal inspiration, after Mundine's release of his 2007 single, Platinum Ryder.[27]

[edit] Art

Australia has a tradition of Aboriginal art which is thousands of years old, the best known forms being rock art and bark painting. These paintings usually consist of paint using earthly colours, specifically, from paint made from ochre. Traditionally, Aborigines have painted stories from their Dreamtime.

Modern Aboriginal artists continue the tradition, using modern materials in their artworks. Aboriginal art is the most internationally recognisable form of Australian art[citation needed]. Several styles of Aboriginal art have developed in modern times, including the watercolour paintings of Albert Namatjira; the Hermannsburg School, and the acrylic Papunya Tula "dot art" movement. }

Australian Aboriginal poetry - ranging from sacred to everyday - is found throughout the continent. [28]

[edit] Traditional recreation

The Djab wurrung and Jardwadjali people of western Victoria once participated in the traditional game of Marn Grook, a type of football played with a ball made of possum hide.[30] The game is believed by some to have inspired Tom Wills, inventor of the code of Australian rules football, a popular Australian winter sport. The Wills family had strong links to Indigenous people and Wills coached the first Australian cricket side to tour England, the Australian Aboriginal cricket team in England in 1868.

[edit] Population

In 1983 the High Court of Australia[31] defined an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander as "a person of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent who identifies as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander and is accepted as such by the community in which he or she lives".

The ruling was a three-part definition comprising descent, self-identification and community identification. The first part - descent - was genetic descent and unambiguous, but led to cases where a lack of records to prove ancestry excluded some. Self- and community identification were more problematic as they meant that an Indigenous person separated from her or his community due to a family dispute could no longer identify as Aboriginal.

As a result there arose court cases throughout the 1990s where excluded people demanded that their Aboriginality be recognised. In 1995, Justice Drummond ruled "..either genuine self-identification as Aboriginal alone or Aboriginal communal recognition as such by itself may suffice, according to the circumstances."

Judge Merkel in 1998 defined Aboriginal descent as technical rather than real - thereby eliminating a genetic requirement.[32] This decision established that anyone can classify him or herself legally as an Aboriginal, provided he or she is accepted as such by his or her community. As there is no formal procedure for any community to record acceptance, the primary method of determining Indigenous population is from self-identification on census forms.

There is no provision on the forms to differentiate 'full' from 'part' Indigenous or to identify non-Indigenous persons accepted by Indigenous communities, but who have no genetic descent.[33]

The Australian Bureau of Statistics 2005 snapshot of Australia showed that the Indigenous population had grown at twice the rate of the overall population since 1996 when the Indigenous population stood at 283,000. As of June 2001, the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated the total resident Indigenous population to be 458,520 (2.4% of Australia's total), 90% of whom identified as Aboriginal, 6% Torres Strait Islander and the remaining 4% being of dual Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parentage. Much of the increase since 1996 can be attributed to greater numbers of people identifying themselves as Aborigines and to changed definitions of aboriginality.

Based on Census data at 30 June 2006, the preliminary estimate of Indigenous resident population of Australia was 517,200, broken down as follows:

- New South Wales – 148,200

- Queensland – 146,400

- Western Australia – 77,900

- Northern Territory – 66,600

- Victoria – 30,800

- South Australia – 26,000

- Tasmania – 16,900

- ACT – 4,000

- and a small number in other Australian territories [34]

While the State with the largest total Indigenous population is New South Wales, as a percentage this group constitutes only 2.2% of the overall population of the State. The Northern Territory has the largest Indigenous population in percentage terms for a State or Territory, with 31.6%. All the other States and Territories have less than 4% of their total populations identifying as Indigenous; Victoria has the lowest percentage. (0.6%).[34]

As of 2006 about 31% of the Indigenous population was living in 'major cities' (as defined by the Australian Bureau of Statistics/Australian Standard Geographical Classification) and another 45% in 'regional Australia', with the remaining 24% in remote areas. The populations in Victoria, South Australia, and New South Wales are more likely to be urbanised.[35]

The proportion of Aboriginal adults married (de facto or de jure) to non-Aboriginal spouses was 69% according to the 2001 census, up from 64% in 1996, 51% in 1991 and 46% in 1986. The census figures show there were more intermixed Aboriginal couples in capital cities: 87% in 2001 compared to 60% in rural and regional Australia. [36]

[edit] Groups and communities

Throughout the history of the continent, there have been many different Aboriginal groups, each with its own individual language, culture, and belief structure. At the time of British settlement, there were over 200 distinct languages.

There are an indeterminate number of Indigenous communities, comprising several hundred groupings. Some communities, cultures or groups may be inclusive of others and alter or overlap; significant changes have occurred in the generations after colonisation.

The word 'community' is often used to describe groups identifying by kinship, language or belonging to a particular place or 'country'. A community may draw on separate cultural values and individuals can conceivably belong to a number of communities within Australia; identification within them may be adopted or rejected.

An individual community may identify itself by many names, each of which can have alternate English spellings. The largest Aboriginal communities - the Pitjantjatjara, the Arrernte, the Luritja and the Warlpiri - are all from Central Australia.

| This section requires expansion. |

Tasmania

The Tasmanian Aborigines are thought to have first crossed into Tasmania approximately 40,000 years ago via a land bridge between the island and the rest of mainland Australia during the last glacial period.[citation needed] The original population, estimated at 4,000 to 6,000 people, was reduced to a population of around 300 between 1803 and 1833 due to the introduced diseases[37] and actions of British settlers.[citation needed]

Almost all of the Tasmanian Aboriginal peoples today are descendants of two women: Fanny Cochrane Smith and Dolly Dalrymple.[citation needed] A woman named Truganini, who died in 1876, is generally considered to be the last first-generation (full‐blooded) tribal Tasmanian Aborigine, while Fanny Cochrane Smith, who died in 1905, is recognised as the last of the Tasmanian Aborigines.[citation needed] This conflict is a subject of the Australian history wars.[38]

[edit] Contemporary issues

The Indigenous Australian population is a mostly urbanised demographic, but a substantial number (27% as of 2002[39]) live in remote settlements often located on the site of former church missions. The health and economic difficulties facing both groups are substantial. Both the remote and urban populations have adverse ratings on a number of social indicators, including health, education, unemployment, poverty and crime.[40]

In 2004 former Prime Minister John Howard initiated contracts with Aboriginal communities, where substantial financial benefits are available in return for commitments such as ensuring children attend school. These contracts are known as Shared Responsibility Agreements. This saw a political shift from 'self determination' for Aboriginal communities to 'mutual obligation'[41], which has been criticised as a "paternalistic and dictatorial arrangement"[42].

The "Mutual Obligation" concept was introduced for all Australians in receipt of welfare benefits and who are not disabled or elderly[43]. Notably, just prior to a federal election being called, John Howard in a speech at the Sydney Institute on October 11, 2007 acknowledged some of the failures of the previous policies of his government and said "We must recognise the distinctiveness of Indigenous identity and culture and the right of Indigenous people to preserve that heritage. The crisis of Indigenous social and cultural disintegration requires a stronger affirmation of Indigenous identity and culture as a source of dignity, self-esteem and pride."

[edit] Stolen Generations

The Stolen Generations were those children of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who were removed from their families by the Australian Federal and State government agencies and church missions, under acts of their respective parliaments.[44][45] The removals occurred in the period between approximately 1869[46] and 1969,[47][48] although, in some places, children were still being taken in the 1970s.[49]

On February 13, 2008, the federal government of Australia, led by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, issued a formal apology to the Indigenous Australians over the Stolen Generations.[50]

[edit] Political representation

Under Section 41 of the Australian Constitution Aboriginals always had the legal right to vote in Australian Commonwealth elections if their State granted them that right. This meant that all Aborigines outside Queensland and Western Australia had a legal right to vote. Indigenous Australians gained the unqualified right to vote in Federal elections in 1962.

It was not until 1967 that they were counted in the population for the purpose of distribution of electoral seats. Only two Indigenous Australians have been elected to the Australian Parliament, Neville Bonner (1971–1983) and Aden Ridgeway (1999–2005). There are currently no Indigenous Australians in the Australian Parliament.

ATSIC, the representative body of Aborigine and Torres Strait Islanders, was set up in 1990 under the Hawke government. In 2004, the Howard government disbanded ATSIC and replaced it with an appointed network of 30 Indigenous Coordination Centres that administer Shared Responsibility Agreements and Regional Partnership Agreements with Aboriginal communities at a local level.[51]

In October 2007, just prior to the calling of a federal election, the then Prime Minister, John Howard, advocated a referendum to recognise Indigenous Australians in the Constitution. Reaction to his surprising adoption of the importance of the symbolic aspects of the reconciliation process, was mixed. The ALP supported the idea. Some sections of the Australian public and media [9] suggested it was a cynical attempt in the lead-up to an election to whitewash Mr Howard's poor handling of this issue during his term in office. David Ross (Central Land Council) said "its a new skin for an old snake." [52] (ABC radio 12 October 2007)

[edit] Age characteristics

The Indigenous population of Australia is much younger than the non-Indigenous population, with an estimated median age of 21 years (37 years for non-Indigenous), due to higher rates of birth and death.[53] For this reason, age standardisation is often used when comparing Indigenous and non-Indigenous statistics.[39]

[edit] Education

Students as a group leave school earlier, and live with a lower standard of education, compared with their peers. Although the situation is slowly improving (with significant gains between 1994 and 2002),[39]

- 39% of indigenous students stayed on to year 12 at high school, compared with 75% for the Australian population as a whole. ABS

- 22% of indigenous adults had a vocational or higher education qualification, compared with 48% for the Australian population as a whole . ABS

- 4% of Indigenous Australians held a bachelor degree or higher, compared with 21% for the population as a whole. While this fraction is increasing, it is increasing at a slower rate than that for Australian population as a whole. ABS

The performance of indigenous students in national literacy and numeracy tests conducted in school years three, five, and seven is also inferior to that of their peers. The following table displays the performance of indigenous students against the general Australian student population as reported in the National Report on Schooling in Australia 2004.[54]

| Reading | Writing | Numeracy | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indigenous |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Australia |

|

|

|

In response to this problem, the Commonwealth Government formulated a National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education Policy. A number of government initiatives have resulted, some of which are listed by the Commonwealth Government's Indigenous Education page.

[edit] Employment

Indigenous Australians as a group generally experience high unemployment compared to the national average. For instance, in August 2001, the (non-age-standardised) unemployment rate for Indigenous Australians was 20.0%, compared to 7.2% for non-Indigenous Australians. The difference is not solely due to the increased proportion of Indigenous Australians living in rural communities, for unemployment is higher in Indigenous Australian populations living in urban centres than for non-Indigenous populations in the same regions (Source: ABS). As of 2002, the average household income for Indigenous Australian adults (adjusted for household size and composition) was 60% of the non-Indigenous average.[39].

[edit] Health

Due to lack of access to medical facilities, Indigenous Australians were twice as likely to report their health as fair/poor and one-and-a-half times more likely to have a disability or long-term health condition (after adjusting for demographic structures).[39]

Health problems with the highest disparity (compared with the non-Indigenous population) in incidence [55] are outlined in the table below:

| Health complication | Comparative incidence rate | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Circulatory system | 2 to 10-fold | 5 to 10-fold increase in rheumatic heart disease and hypertensive disease, 2-fold increase in other heart disease, 3-fold increase in death from circulatory system disorders. Circulatory system diseases account for 24% deaths[56] |

| Renal failure | 2 to 3-fold | 2 to 3-fold increase in listing on the dialysis and transplant registry, up to 30-fold increase in end stage renal disease, 8-fold increase in death rates from renal failure, 2.5% of total deaths [56] |

| Communicable | 10 to 70-fold | 10-fold increase in tuberculosis, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C virus, 20-fold increase in Chlamydia, 40-fold increase in Shigellosis and Syphilis, 70-fold increase in Gonococcal infections |

| Diabetes | 3 to 4-fold | 11% incidence of Type 2 Diabetes in Indigenous Australians, 3% in non-Indigenous population. 18% of total indigenous deaths [56] |

| Cot death | 2 to 3-fold | Over the period 1999–2003, in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory, the national cot death rate for infants was three times the rate |

| Mental health | 2 to 5-fold | 5-fold increase in drug-induced mental disorders, 2-fold increase in diseases such as schizophrenia, 2 to 3-fold increase in suicide..[57] |

| Optometry/Ophthalmology | 2-fold | A 2-fold increase in cataracts |

| Neoplasms | 60% increase in death rate | 60% increased death rate from neoplasms. In 1999–2003, neoplasms accounted for 17% of all deaths[56] |

| Respiratory | 3 to 4-fold | 3 to 4-fold increased death rate from respiratory disease accounting for 8% of total deaths |

Each of these indicators is expected to underestimate the true prevalence of disease in the population due to reduced levels of diagnosis.[55]

In addition, the following factors have been at least partially implicated in the inequality in life expectancy:[39][55]

- poverty

- insufficient education

- substance abuse [58][59]

- for remote communities poor access to health services

- for urbanised Indigenous Australians, cultural pressures which prevent access to health services

- cultural differences resulting in poor communication between Indigenous Australians and health workers.

Successive Federal Governments have responded to these issues by implementing programs such as the Office of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health (OATSIH). Which effected by bringing health services into indigenous communities, but on the whole the problem still remains challenging.

[edit] Crime

An Indigenous Australian is 11 times more likely to be in prison (age-standardised figures), and in June 2004, 21% of prisoners in Australia were Indigenous.[60]

In 2002, Indigenous Australians were twice as likely as their non-Indigenous peers to be a victim of violent aggression,[60] with 24% of Indigenous Australians reported as being a victim of violence in 2001.[60]

See also: Northern Territory National Emergency Response

[edit] Substance abuse

Many Indigenous communities suffer from a range of health and social problems associated with substance abuse of both legal and illegal drugs.

A large 2004–05 health survey by the ABS found that the proportion of the Indigenous adult population engaged in 'risky' and 'high-risk' alcohol consumption (15%) was comparable with that of the non-Indigenous population (14%), based on age-standardised data. [61] The percentage-point difference between the two figures quoted is not statistically significant, and a similar result was obtained in the earlier 2000–01 survey.

The same health survey found that, after adjusting for age differences between the two populations, Indigenous adults were more than twice as likely as non-Indigenous adults to be current daily smokers of tobacco.[62]

To combat the problem, a number of programs to prevent or mitigate against alcohol abuse have been attempted in different regions, many initiated from within the communities themselves. These strategies include such actions as the declaration of "Dry Zones" within indigenous communities, prohibition and restriction on point-of-sale access, and community policing and licensing.

Some communities (particularly in the Northern Territory) introduced kava as a safer alternative to alcohol, as over-indulgence in kava produces sleepiness, in contrast to the violence that can result from over-indulgence in alcohol. These and other measures met with variable success, and while a number of communities have seen decreases in associated social problems caused by excessive drinking, others continue to struggle with the issue and it remains an ongoing concern.

The ANCD study notes that in order to be effective, programs in general need also to address "...the underlying structural determinants that have a significant impact on alcohol and drug misuse" (Op. cit., p.26). In 2007, Kava was banned in the Northern Territory[63].

Petrol sniffing is also a problem among some remote Indigenous communities. Petrol vapour produces euphoria and dulling effect in those who inhale it, and due to its previously low price and widespread availability, is an increasingly popular substance of abuse.

Proposed solutions to the problem are a topic of heated debate among politicians and the community at large.[64][65] In 2005 this problem among remote indigenous communities was considered so serious that a new, low aromatic petrol Opal was distributed across the Northern Territory to combat it.[66].

[edit] Prominent Indigenous Australians

After the arrival of European settlers in New South Wales, some Indigenous Australians became translators and go-betweens; the best-known was Bennelong, who eventually adopted European dress and customs and travelled to England where he was presented to King George III. Others, such as Pemulwuy, became famous for armed resistance to the European settlers.

During the twentieth century, as social attitudes shifted and interest in Indigenous culture increased, there were more opportunities for Indigenous Australians to gain recognition. Albert Namatjira became one of Australia's best-known painters, and actors such as David Gulpilil, Ernie Dingo, and Deborah Mailman became well known. Bands such as Yothu Yindi have successfully combined Indigenous musical styles and instruments with pop/rock, gaining wide appreciation amongst non-Indigenous audiences.

Indigenous Australians have also been prominent in sport. Lionel Rose earned a world title in boxing, Evonne Goolagong became a number-one ranked tennis player with 14 Grand Slam titles, and runner Cathy Freeman earned gold medals in the Olympics, World Championships, and Commonwealth Games; many more Indigenous athletes are active at national and international level.

While relatively few Indigenous Australians have been elected to political office (Neville Bonner and Aden Ridgeway remain the only ones to have been elected to the Australian Senate), many have become famous through political activism - for instance, Charles Perkins' involvement in the Freedom Ride of 1965 and subsequent work, and Torres Strait Islander Eddie Mabo's part in the landmark native title decision that bears his name. Others who initially became famous in other spheres - for instance, poet Oodgeroo Noonuccal - have used their celebrity to draw attention to Indigenous issues.

[edit] See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Australian Aboriginals |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[edit] References

- ^ [1]Australian Bureau of Statistics

- ^ Tim Flannery (1994), The Future Eaters: An Ecological History of the Australasian Lands and People, ISBN 0-8021-3943-4 ISBN 0-7301-0422-2

- ^ "When did Australia's earliest inhabitants arrive?", University of Wollongong, 2004. Retrieved June 6, 2008

- ^ "Aboriginal truth and white media: Eric Michaels meets the spirit of Aboriginalism", The Australian Journal of Media & Culture, vol. 3 no 3, 1990. Retrieved June 6, 2008

- ^ "Australian Social Trends" Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1999, Retrieved on June 6, 2008,

- ^ a b c Nathan, D: "Aboriginal Languages of Australia", Aboriginal Languages of Australia Virtual Library, "http://www.dnathan.com/VL/austLang.htm" 2007

- ^ a b c 1301.0 - Year Book Australia, 2002 Australian Bureau of Statistics January 25, 2002

- ^ Pardoe, C: "Becoming Australian: evolutionary processes and biological variation from ancient to modern times", Before Farming 2006, Article 4, 2006

- ^ Originally used by the Romans to denote the (mythical) indigenous people of ancient Italy; see Sallust, Bellum Catilinae, ch. 6.

- ^ UNSW guide on How to avoid Discriminatory Treatment on Racial of Ethnic Grounds

- ^ Appropriate Terms for Australian Aboriginal People

- ^ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, Australian Bureau of Statistics 2004. Accessed 21 June 2007.

- ^ a b c Places – Torres Strait Islands ABC Radio Australia website, 2005. Accessed 21 June 2007.

- ^ Chris Gibson, Peter Dunbar-Hall, Deadly Sounds, Deadly Places: Contemporary Aboriginal Music in Australia, pp. 120–121 (UNSW Press, 2005)

- ^ Bowern, Claire and Harold Koch (eds.). 2004. Australian Languages: Classification and the comparative method. John Benjamins, Sydney.

- ^ Dixon, R.M.W. 1997. The Rise and Fall of Languages. CUP.

- ^ BC [Before Cook and Colonisation]

- ^ Smallpox Through History

- ^ "Year Book Australia, 2002". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2002. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/94713ad445ff1425ca25682000192af2/bfc28642d31c215cca256b350010b3f4!OpenDocument. Retrieved on 2008-09-23.

- ^ Tatz, C. (1999, 2005). Aboriginal Suicide Is Different. Aboriginal Studies Press. [2]

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics – Religion

- ^ Phil Mercer (31 March 2003). "Aborigines turn to Islam". BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/2902315.stm. Retrieved on 2007-05-25.

- ^ http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/a-new-faith-for-kooris/2007/05/03/1177788310619.html A new faith for Kooris

- ^ Andrews, M. (2004) 'The Seven Sisters', Spinifex Press, North Melbourne, p. 424

- ^ http://www.aboriginalarts.co.uk/historyofthedidgeridoo.html

- ^ http://www.theage.com.au/news/music/the-new-corroboree/2006/03/30/1143441270792.html?page=fullpage

- ^ http://www.smh.com.au/news/music/the-man-must-make-his-music/2007/03/25/1174761263365.html

- ^ Ronald M. Berndt has published traditional Aboriginal song-poetry in his book "Three Faces of Love", Nelson 1976. R.M.W. Dixon and M. Duwell have published two books dealing with sacred and everyday poetry: "The Honey Ant Men's Love Song" and "Little Eva at Moonlight Creek", University of Queensland Press, 1994".

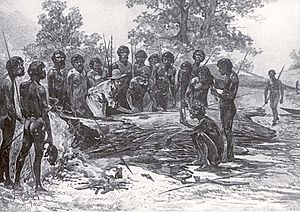

- ^ (From William Blandowski's Australien in 142 Photographischen Abbildungen, 1857, (Haddon Library, Faculty of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge)

- ^ Kids play "kick to kick" -1850s style from abc.net.au

- ^ Commonwealth v Tasmania [1983] HCA 21; (1983) 158 CLR 1 (1 July 1983)

- ^ Defining Indigenousness and asserting Aboriginal identity. Tyson Yunkaporta Jun 6, 2007

- ^ John Gardiner-Garden (2000-10-05). "The Definition of Aboriginality". Parliamentary Library. Parliament of Australia. http://www.aph.gov.au/LIBRARY/pubs/rn/2000-01/01RN18.htm. Retrieved on 2008-02-05.

- ^ a b Population Distribution, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians Australian Bureau of Statistics 15 AUG 2007 pdf.

- ^ Population Distribution, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006

- ^ Birrell, R and J Hirst, 2002, Aboriginal Couples at the 2001 Census, People and Place, 10(3): 27

- ^ Historian dismisses Tasmanian aboriginal genocide "myth",PM show, ABC Local Radio, 12 December 2002. Transcript accessed 22 June 2007

- ^ Historian admits misquoting governor Arthur over Aboriginal attacks, smh.com.au

- ^ a b c d e f Australian Bureau of Statistics

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics. Year Book Australia 2005

- ^ Nothing mutual about denying Aborigines a voice, Larissa Behrendt, The Age newspaper, December 8, 2004 [4]

- ^ Mutual Obligation Requirements

- ^ Bringing them Home, Appendices listing and interpretation of state acts regarding 'Aborigines': Appendix 1.1 NSW; Appendix 1.2 ACT; Appendix 2 Victoria; Appendix 3 Queensland; Tasmania; Appendix 5 Western Australia; Appendix 6 South Australia; Appendix 7 Northern Territory.

- ^ Bringing them home education module: the laws: Australian Capital Territory; New South Wales; Northern Territory; Queensland Queensland; South Australia; Tasmania ; Victoria ; Western Australia

- ^ Marten, J.A., (2002), Children and war, NYU Press, New York, p. 229 ISBN 0814756670

- ^ Australian Museum (2004). "Indigenous Australia: Family". http://www.dreamtime.net.au/indigenous/family.cfm#bi. Retrieved on 2008-03-28.

- ^ Read, Peter (1981) (PDF). The Stolen Generations: The Removal of Aboriginal children in New South Wales 1883 to 1969. Department of Aboriginal Affairs (New South Wales government). ISBN 0-646-46221-0. http://www.daa.nsw.gov.au/publications/StolenGenerations.pdf.

- ^ In its submission to the Bringing Them Home report, the Victorian government stated that "despite the apparent recognition in government reports that the interests of Indigenous children were best served by keeping them in their own communities, the number of Aboriginal children forcibly removed continued to increase, rising from 220 in 1973 to 350 in 1976" (Bringing Them Home: "Victoria")

- ^ "Rudd says sorry", Dylan Welch, Sydney Morning Herald February 13, 2008

- ^ "Coordination and engagement at regional and national levels". Administration. Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination. 2006. http://www.oipc.gov.au/About_OIPC/Indigenous_Affairs_Arrangements/4Administration.asp. Retrieved on 2006-05-17.

- ^ (ABC Television News 12 October 2007)Patrick Dodson said "I think it's a positive contribution to the process of national reconciliation...It's obviously got to be well discussed and considered and weighed, and it's got to be about meaningful and proper negotiations that can lead to the achievement of constitutional reconciliation."

- ^ "4704.0 - The Health and Welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, 2008". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2008. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/39433889d406eeb9ca2570610019e9a5/D5D682247B842263CA25743900149BB7?opendocument. Retrieved on 2009-01-08.

- ^ Chapter 10: Indigenous education

- ^ a b c Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. [5]

- ^ a b c d Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. [6]

- ^ T. Vos, B. Barker, L. Stanley, A Lopez (2007). The burden of disease and injury in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: Summary report, page 14. Brisbane: School of Population Health, University of Queensland. [7]

- ^ Petrol Sniffing - Health & Wellbeing

- ^ Alcohol and Other Drugs - Petrol

- ^ a b c "4102.0 - Australian Social Trends, 2005: Crime and Justice: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: Contact with the Law ABS". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 12/07/2005. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/94713ad445ff1425ca25682000192af2/a3c671495d062f72ca25703b0080ccd1. Retrieved on 2007-04-28.

- ^ Australian Statistician (2006) (PDF). National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2004-05 (ABS Cat. 4715.0), Table 6.. pdf. Australian Bureau of Statistics. http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/B1BCF4E6DD320A0BCA25714C001822BC/$File/47150_2004-05.pdf. Retrieved on 2006-06-01.The definition of "risky" and "high-risk" consumption used is four or more standard drinks per day average for males, two or more for females.

- ^ Australian Statistician (2006) (PDF). National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2004-05 (ABS Cat. 4715.0), Table 1.. pdf. Australian Bureau of Statistics. http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/B1BCF4E6DD320A0BCA25714C001822BC/$File/47150_2004-05.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-06-23.

- ^ Australian Broadcasting Commission (2007) "Kava Ban 'Sparks Black Market Boom'", ABC Darwin 23 August 2007 http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2007/08/23/2012707.htm?site=darwin Accessed 18 October 2007

- ^ Effects of sniffing petrol Northern Territory Government Health Department

- ^ Petrol Sniffing in Remote Northern Territory Communities Legislative Assembly of the Northern Territory

- ^ Australian Health Ministry

[edit] Further reading

- Jamison, T. The Australian Aboriginal People: Dating the Colonization of Australia

- Windschuttle, K & Gillin, T. The extinction of the Australian pygmies

Roberts, Jan. "Jack of Cape Grim: A story of British Invasion and Aboriginal Resistance" 2008 edition available from Amazon

Roberts, Jan. "Massacres to Mining: The Colonisation of Aboriginal Australia." 2008 edition available from Amazon.

[edit] External links

- Aboriginal Australia Online

- Aboriginal Studies Virtual Library

- Aborigines win 'native title' over Perth

- Australia's largest circulating Indigenous Affairs Newspaper

- Australian, Bosnian and Norwagian [sic] Cross-Bred Children

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (May 14, 2007). "Law and justice statistics - Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: a snapshot, 2002". http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/mf/4722.0.55.003?OpenDocument.

- Ceremony The Djungguwan of Northeast Arnhem Land

- Educational Resources for students

- Classroom Resources

- Department of Indigenous Affairs (Australian Government)

- European Network for Indigenous Australian Rights

- Joel Gibson (1 May 2007). "Australia worst in the world for indigenous health". stuff.com.nx. http://www.stuff.co.nz/4044438a12.html. Retrieved on 2007-05-25.

- Indigenous Australia – Australian Museum educational site

- Indigenous Australians - State Library of NSW

- Indigenous Business/Employment in Darwin NT

- KooriWeb

- Latest Indigenous news from ABC News Online

- Norman B. Tindale's Catalogue of Aboriginal Tribes

- Original Girl Mari Miyay virtual book – Read and hear the story of Emily, a Gamilaraay girl, written by her mother, Michelle Witheyman-Crump with Gamilaraay translation. Held by the State Library of Queensland

- Reconciliation Australia

- Indigenous Language Map