Thoracic outlet syndrome

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Thoracic outlet syndrome Classification and external resources |

|

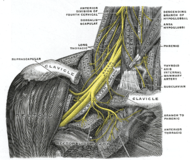

| The right brachial plexus with its short branches, viewed from in front. | |

| ICD-10 | G54.0 |

| ICD-9 | 353.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 13039 |

| MedlinePlus | 001434 |

| eMedicine | pmr/136 |

| MeSH | D013901 |

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) consists of a group of distinct disorders that affect the brachial plexus (nerves that pass into the arms from the neck), and/or the subclavian artery and vein (blood vessels that pass between the chest and upper extremity).

Contents |

[edit] Causes

For the most part, these disorders are produced by compression of the components of the brachial plexus (the large cluster of nerves that pass from the neck to the arm), the subclavian artery, or the subclavian vein. These subtypes are referred to as neurogenic TOS, arterial TOS, and venous TOS, respectively. The compression may be positional (caused by movement of the clavicle (collarbone) and shoulder girdle on arm movement) or static (caused by abnormalities or enlargement of the various muscles surrounding the arteries, veins and brachial plexus).

The neurogenic form of TOS accounts for 95 to 98% of all cases of TOS.

It is known from pathological studies of cadavers, and from surgical studies of patients with TOS, that there are numerous anomalies of the scalene muscles and the other muscles that surround the arteries, veins and brachial plexus. TOS may result from these anomalies of the scalene muscles or from enlargement (hypertrophy) of the scalene muscles. One common cause of hypertrophy is trauma, as may occur in motor vehicle accidents.

The two groups of people most likely to develop TOS are those suffering neck injuries in motor vehicle accidents and those who use computers in non-ergonomic postures for extended periods of time. Young overhead athletes (such as swimmers, volleyball players and baseball pitchers) and musicians may also develop thoracic outlet syndrome, but significantly less frequently than the two large groups above.

[edit] Classification

The following taxonomy of TOS is used in ICD-9-CM and older sources:

- Scalenus anticus syndrome (compression on brachial plexus and/or subclavian artery caused by muscle growth) - diagnosed by using Adson's sign with patient's head turned outward

- Cervical rib syndrome (compression on brachial plexus and/or subclavian artery caused by bone growth) - diagnosed by using Adson's sign with patient's head turned inward

- Costoclavicular syndrome (narrowing between the clavicle and the first rib) -- diagnosed with costoclavicular maneuver

A more modern system of classification is provided on the website of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS).[1]

[edit] Diagnosis

Adson's sign and the costoclavicular maneuver are notoriously inaccurate, and may be a small part of a comprehensive history and physical examination of a patient with TOS. There is currently no single clinical sign that makes the diagnosis of TOS with certainty. Arteriography, while only rarely used to evaluate thoracic outlet syndrome, may be used if a surgery is being planned to correct an arterial TOS.[2]

[edit] Treatment

Often, continued and active postural changes along with physiotherapy, massage therapy, chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation, will suffice. The recovery process however is long term, and a few days of poor posture can often set one back.

About 10 to 15% of patients undergo surgical decompression following an appropriate trial of conservative therapy, most often specific physical therapy directed towards the treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome, and usually lasting between 6 and 12 months. Surgical treatment may include removal of anomalous muscles, removal of the native anterior and/or middle scalene muscles, removal of the first rib or, if present, a cervical rib, or neurolysis (removal of fibrous tissue from the brachial plexus).

[edit] Noninvasive

- Stretching

The goal of self stretching is to relieve compression in the thoracic cavity, reduce blood vessel and nerve impingement, and realign the bones, muscles, ligaments, and tendons causing the problem.- Moving shoulders forward (hunching) then back to neutral, followed by extending them back (arching) then back to neutral, followed by lifting shoulders then back to neutral.

- Tilting and extending neck opposite to the side of injury while keeping the injured arm down or wrapped around the back.

- Nerve Gliding

This syndrome causes a compression of a large cluster of nerves, resulting in the impairment of nerves throughout the arm. By performing nerve gliding exercises one can stretch and mobilize the nerve fibers. Chronic and intermittent nerve compression has been studied in animal models, and has a well-described pathophysiology, as described by Susan Mackinnon, MD, currently at Washington University in St. Louis. Nerve gliding exercises have been studied by several authorities, including David Butler in Australia.- Extend your injured arm with fingers directly outwards to the side. Tilt your head to the otherside, and/or turn your head to the other side. A gentle pulling feeling is generally felt throughout the injured side. Initially, only do this and repeat. Once this exercise has been mastered and no extreme pain is felt, begin stretching your fingers back. Repeat with different variations, tilting your hand up, backwards, or downwards.

- Posture

TOS is rapidly aggravated by poor posture. Active breathing exercises and ergonomic desk setup can both help maintain active posture. Often the muscles in the back become weak due to prolonged (years) hunching. - Ice/Heat

Ice can be used to decrease inflammation of sore or injured muscles. Heat can also aid in relieving sore muscles by improving circulation to them. While the whole arm generally feels painful, some relief can be seen when ice/heat is applied to the thoracic region (collar bone, armpit, or shoulder blades).

[edit] Invasive

- Cortisone

Injected into a joint or muscle, cortisone can help relief and lower inflammation.[dubious ] - Botox injections

Short for Botulinum Toxin A, Botox binds nerve endings and prevents the release of neurotransmitters that activate muscles. A small amount of Botox injected into the tight or spastic muscles (usually one or all three scalenes) found in TOS sufferers often provides months of relief while the muscle is temporarily paralyzed. This noncosmetic treatment is unfortunately not covered by most medical plans and costs upwards of $400. The relief of symptoms from a Botox injection generally lasts 3-4 months, at which point the Botox toxin is degraded by the affected muscles. Serious side effects have been reported, and are similarly long-lasting, so improved understanding of the mechanism of a 'scalene block' is vital to determining the benefit and risk of using Botox.

Surgical approaches have also been used.[3]

Some physicians advocate the injection of a short-acting anesthetic such as xylocaine into the anterior scalene, subclavius, or pectoralis minor muscles as a provocative test to assist in the diagnosis of thoracic outlet syndrome. This is referred to as a 'scalene block'. If the patient experiences symptomatic relief for approximately 15 minutes following this procedure, surgical decompression is more likely to be successful in leading to the same level of symptomatic relief. However, this is not considered a 'treatment', as the relief is expected to wear off within an hour or two, at a maximum. Active research continues into the accuracy and risks of this provocative test.

[edit] Notable patients

Major League Baseball players Hank Blalock, John Rheinecker, Jeremy Bonderman, and Kenny Rogers have recently been diagnosed with Thoracic outlet syndrome. Kenny Rogers was diagnosed several years earlier with TOS in the other upper extremity. Coincidentally, three of these four players have played for the Texas Rangers. All-Star pitcher J. R. Richard suffered a career-ending stroke from an undiagnosed case of TOS. Pitcher David Cone had a variant case of TOS, with an arterial aneurysm of the upper aspect of his pitching arm.

Overhead athletes, such as swimmers and volleyball players, are known to be predisposed to the development of TOS.

Musician Isaac Hanson suffered a potentially life threatening pulmonary embolism as a complication to thoracic outlet syndrome.[4]

[edit] References

- ^ NINDS Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Information Page

- ^ Thoracic outlet syndrome Mount Sinai Hospital, New York

- ^ Rochkind S, Shemesh M, Patish H, et al (2007). "Thoracic outlet syndrome: a multidisciplinary problem with a perspective for microsurgical management without rib resection". Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 100: 145–7. PMID 17985565.

- ^ "People Magazine". http://www.hanson.net/site/hanson/blog_entry/1?entry_id=5832. Retrieved on 2008-01-01.

[edit] External links

- thoracic at NINDS

- American Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Association [1]

- Tos-Syndrome.com

- NeoVista MRI Graphic illustrations of TOS, the history of TOS, and information about the diagnosis of TOS

- Journal of American Chiropractic Association

- Adson's test [2]

- Physical Therapy Corner - Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

- Society for Vascular Surgery (U.S.)

- Division of Vascular Surgery and Endovascular Therapy at the Baylor College of Medicine