Effects of the automobile on societies

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. Please improve this article or discuss the issue on the talk page. |

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Please see the discussion on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until the dispute is resolved. (January 2008) |

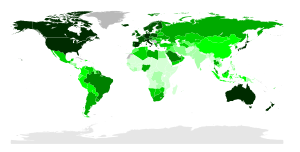

Over the course of the 20th century, the automobile rapidly developed from an expensive toy for the rich into the de facto standard for passenger transport in most developed countries.[1] In developing countries, the effects of the automobile have lagged, but are emulating the impacts of developed nations. The development of the automobile built upon the transport revolution started by railways, and like the railways, introduced sweeping changes in employment patterns, social interactions, infrastructure and goods distribution.

The effects of automobiles on everyday life have been a subject of controversy. While the introduction of the mass-produced automobile represented a revolution in mobility and convenience, the modern consequences of heavy automotive use contribute to the use of non-renewable fuels, a dramatic increase in the rate of accidental death, social isolation and the disconnection of community, rise in obesity, the generation of air and noise pollution, and the facilitation of urban sprawl and urban decay[2].

Contents |

[edit] Economic changes

The development of the automobile has contributed to changes in employment distribution, shopping patterns, social interactions, manufacturing priorities and city planning; increasing use of automobiles has reduced the roles of walking, horses and railroads.[3]

[edit] Infrastructure

Aside from industries, one of the most visible effects the automobile has had on the world is the huge increase in the amount of surfaced roads. For example, between 1921 and 1941, the United States spent US$40 billion on roads, increasing the amount of surfaced road from 387,000 miles (619,000 kilometers) to over 1,000,000 miles (1.6 million kilometers) which does not even take into account road widening.[2]

[edit] United States

In addition to federal, state, and local dollars for roadway construction, car use was also encouraged through new zoning laws that required that any new business construct a certain amount of parking based on the size and type of facility. The effect of this was to create a massive quantity of free parking spaces and to push businesses further back from the road. Many shopping centers and suburbs abandon sidewalks altogether, making pedestrian access dangerous. This had the effect of encouraging people to drive, even for short trips that might have been walkable, thus increasing and solidifying American auto-dependency.[4] As a result of this change, employment opportunities for people who were not wealthy enough to own a car and for people who could not drive, due to age or physical disabilities, became severely limited.[5]

[edit] Environmental impact

For much of the early history of the car, no consideration was given to various environmental effects caused by the automobile. Automobiles are a major source of air pollution and noise pollution. The manufacture and use of automobiles makes up 20 to 25 percent[6] of the carbon dioxide emissions that are widely believed to be causing global climate change. There are over 600 million cars and light vehicles (excluding heavy trucks and buses) worldwide,[7] The automobile contributes significantly to noise pollution worldwide; in response to these impacts, an entire technology of noise barrier design and other noise mitigation has emerged.[8] In the United States the typical car emits approximately 3.4 grams per mile of carbon monoxide[9]

With increased road-building came negative effects on habitat for wildlife, primarily through habitat fragmentation and surface runoff alteration.[6] New roads built through sensitive habitat can cause the loss or degradation of ecosystems, and the materials required for roads come from large-scale rock quarrying and gravel extraction, which sometimes occurs in sensitive ecological areas. Road construction also alters the water table, increases surface runoff, and increases the risk of flooding.[6]

[edit] Cultural changes

Prior to the appearance of the automobile, horses, walking and streetcars were the major modes of transportation within cities.[3] Horses require a large amount of care, and were therefore kept in public facilities that were usually far from residences. The manure they left on the streets also created a sanitation problem.[10] The automobile requires relatively low maintenance and does not directly contribute to the sanitation problems associated with manure.

The automobile made regular medium-distance travel more convenient and affordable, especially in areas without railways. Because automobiles did not require rest, and were faster than horse-drawn conveyances, people were routinely able to travel farther than in earlier times. The construction of highways half a century later continued this revolution in mobility. Some experts suggest that many of these changes began during the Golden age of the bicycle, the preceding era from 1880—1915.[11]

[edit] Changes to urban society

Beginning in the 1940s, most urban environments in the United States lost their streetcars, cable cars, and other forms of light rail, to be replaced by diesel-burning motor coaches or buses. Many of these have never returned, though some urban communities eventually installed subways.

Another change brought about by the automobile is that modern urban pedestrians must be more alert than their ancestors. In the past, a pedestrian had to worry about relatively slow-moving streetcars or other obstacles of travel. With the proliferation of the automobile, a pedestrian has to anticipate safety risks of automobiles at high speeds because cars may cause serious damage to a human.[3]

According to many social scientists, the loss of pedestrian-scale villages has also disconnected communities. Many people in developed countries have less contact with their neighbors and rarely walk unless they place a high value on exercise.[12]

[edit] Advent of suburban society

Because of the automobile, the outward growth of cities accelerated, and the development of suburbs in automobile intensive cultures was intensified.[3] Until the advent of the automobile, factory workers lived either close to the factory or in high density communities farther away, connected to the factory by streetcar or rail. The automobile and the federal subsidies for roads and suburban development that supported car culture allowed people to live in low density communities far from the city center and integrated city neighborhoods.[3] The developing suburbs created few local jobs, due to single use zoning. Hence, residents commuted longer distances to work each day as the suburbs expanded.[2]

[edit] Car culture

The car had a significant effect on the culture of the middle class. Automobiles were incorporated into all parts of life from music to books to movies. Between 1905 and 1908, more than 120 songs were written in which the automobile was the subject. The automotive themes of these songs reflected the general culture of the automotive industry: sexual adventure, liberation from social control, and masculine power.[3] Books centered on motor boys who liberated themselves from the average, normal, middle class life, to travel and seek adventure in the exotic. Car ownership came to be associated with independence, freedom, and increased status.

George Monbiot writes that widespread car culture has shifted voter's preference to the right of the political spectrum.[13] He thinks that car culture has contributed to an increase in individualism and fewer social interactions between members of different socioeconomic classes.

Since the early days of the automobile, car manufacturers and petroleum fuel suppliers successfully lobbied governments to build public roads.[2] Road building was sometimes also influenced by Keynesian-style political ideologies. In Europe, massive freeway building programs were initiated by a number of social democratic governments after World War II, in an attempt to create jobs and make the automobile available to the working classes. From the 1970s, promotion of the automobile increasingly became a trait of some conservatives. Margaret Thatcher talked of a "great car economy", and increased government spending on roads.

[edit] Safety

Motor vehicle accidents are attributed to 44% of accidental deaths in the United States, making them the country's leading cause of accidental death.[14]

[edit] Costs

In countries such as the United States the infrastructure that makes car use possible, such as highways, roads and parking lots is funded by the government and supported through government zoning and construction requirements.[15] The gas tax covers about 60% of highway construction and repair costs.[16][17] Payments by motor-vehicle users fall short of government expenditures tied to motor-vehicle use by 20–70 cents per gallon of gas.[18] Zoning laws in many areas require that large, free parking lots accompany any new buildings. Municipal parking lots are often free or do not charge a market-rate. Hence, the cost of driving a car in the US is subsidized, supported by businesses and the government who cover the cost of roads and parking.[15] This government support of the automobile through subsidies for infrastructure, the cost of highway police enforcement, recovering stolen cars, and many other factors makes public transport a less economically competitive choice for commuters when considering direct out-of-pocket costs. Consumers often make choices based on the direct out-of-pocket costs and underestimate the indirect costs of car ownership, auto insurance and car maintenance.[16] However, globally and in some US cities, tolls and parking fees partially offset these heavy subsidies for driving. Transportation planning policy advocates often support tolls, increased gas taxes, congestion pricing and market-rate pricing for municipal parking as a means of balancing car use in urban centers with more efficient, less environmentally and socially destructive modes of transportation such as buses and trains.

When cities charge market rates for on-street parking and municipal parking garages, and when bridges and tunnels are tolled, driving becomes less competitive in terms of out-of-pocket costs than other modes of transportation. When municipal parking is underpriced and roads are not tolled, most of the cost of vehicle usage is paid for by general government revenue, a subsidy for motor vehicle use. The size of this subsidy dwarfs the federal, state, and local subsidies for the maintenance of infrastructure and discounted fares for public transportation.[16]

By contrast, although there are environmental and social costs for rail, there is a very small impact.[16]

[edit] Access and convenience

Worldwide the automobile has allowed easier access to remote places. However, average journey times to regularly visited places have increased in large cities, especially in Latin America, as a result of widespread automobile adoption. This is due to traffic congestion and the increased distances between home and work brought about by urban sprawl. [19]

Examples of automobile access issues in underdeveloped countries are:

- Paving of the Mexico Pacific Coast highway through Baja California, completing the connection of Cabo San Lucas to California, allowing the first routine travel along that route and the first convenient access to the outside world for villagers along the route. (occurred in the 1950s)

- In Madagascar, approximately 30 percent of the population does not have access to reliable all weather roads.[20]

- In China, there are currently 184 towns and 54,000 villages that have no access to automobile use (or roads at all)[21]

- The origin of HIV explosion in the human population has been hypothesized by CDC researchers to derive in part from more intensive social interactions afforded by new road networks in Central Africa allowing more frequent travel from villagers to cities and higher density development of many African cities in the period 1950 to 1980.[22]

The following developments in retail are partially due to automobile use:

- Drive-thru fast food purchasing

- Gasoline station grocery shopping

[edit] See also

[edit] Alternatives

[edit] Effects

- Externality

- Roadway noise

- Roadway air dispersion modeling

- Traffic congestion

- Urban decay

- Urban sprawl

[edit] Social aspects

[edit] Planning Response

[edit] References

- ^ The ‘System’ of Automobility by John Urry. Theory, Culture & Society, Vol. 21, No. 4-5, 25-39 (2004)

- ^ a b c d Asphalt Nation: how the automobile took over America, and how we can take it back By Jane Holtz Kay Published 1998 ISBN 0520216202

- ^ a b c d e f Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States by Kenneth T. Jackson. 1987. ISBN 0195049837

- ^ Lots of Parking: Land Use in a Car Culture By John A. Jakle, Keith A. Sculle. 2004. ISBN 0813922666

- ^ When Work Disappears by William Julius Wilson. ISBN 0679724176

- ^ a b c "World Carfree Network - Some Statistics". http://www.worldcarfree.net/resources/stats.php.

- ^ Stasenko, Marina (2001). "Number of Cars". The Physics Factbook. http://hypertextbook.com/facts/2001/MarinaStasenko.shtml.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan and Gary L. Latshaw,The Relationship Between Highway Planning and Urban Noise , Proceedings of the ASCE, Urban Transportation Division Specialty Conference, American Society of Civil Engineers, Urban Transportation Division, May 21-23, 1973, Chicago, Illinois

- ^ United States Environmnetal Protection Agency: Emission standards

- ^ Susan Strasser, Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash, Owl Books, 355 pages (1999) ISBN 080506512

- ^ Smith, Robert (1972). A Social History of the Bicycle, its Early Life and Times in America. American Heritage Press.

- ^ From Highway to Superhighway: The Sustainability, Symbolism and Situated Practices of Car Culture Graves-Brown. Social Analysis. Vol. 41, pp. 64-75. 1997.

- ^ George Monbiot, The Guardian, Tuesday December 20, 2005

- ^ Directly from: http://www.benbest.com/lifeext/causes.html See Accident as a Cause of Death

Derived from: National Vital Statistics Report, Volume 50, Number 15 (September 2002) - ^ a b The High Cost of Free Parking by Donald C. Shoup

- ^ a b c d Graph based on data from Transportation for Livable Cities By Vukan R. Vuchic page. 76. 1999. ISBN 0882851616

- ^ MacKenzie, J.J., R.C. Dower, and D.D.T. Chen. 1992. [http://www.wristore.com/goinratwhati.html The Going Rate: What It Really Costs to Drive]. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

- ^ http://www.its.ucdavis.edu/people/faculty/delucchi

- ^ Gilbert, Alan (1996). The mega-city in Latin America. United Nations University Press. ISBN 9280809350.

- ^ Madagascar: The Development of a National Rural Transport Program

- ^ China Through a Lens: Rural Road Construction Speeded Up

- ^ Joseph M.D. McCormick, Susan Fisher-Hoch and Leslie Alan Horvitz, Virus Hunters of the CDC, Turner Publishing (April 1997) ISBN-13: 978-1570363979