Shell sort

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Class | Sorting algorithm |

|---|---|

| Data structure | Array |

| Worst case performance | depends on gap sequence |

| Best case performance | O(n) |

| Average case performance | depends on gap sequence |

| Worst case space complexity | O(n) |

| Optimal | No |

Shell sort is a sorting algorithm that is a generalization of insertion sort, with two observations:

- insertion sort is efficient if the input is "almost sorted", and

- insertion sort is typically inefficient because it moves values just one position at a time.

Contents |

[edit] History

The Shell sort is named after its inventor, Donald Shell, who published the algorithm in 1959.[1] Some older textbooks and references call this the "Shell-Metzner" sort after Marlene Metzner Norton, but according to Metzner, "I had nothing to do with the sort, and my name should never have been attached to it."[2]

[edit] Implementation

The original implementation performs O(n2) comparisons and exchanges in the worst case. A minor change given in V. Pratt's book[3] improved the bound to O(n log2 n). This is worse than the optimal comparison sorts, which are O(n log n).

Shell sort improves insertion sort by comparing elements separated by a gap of several positions. This lets an element take "bigger steps" toward its expected position. Multiple passes over the data are taken with smaller and smaller gap sizes. The last step of Shell sort is a plain insertion sort, but by then, the array of data is guaranteed to be almost sorted.

Consider a small value that is initially stored in the wrong end of the array. Using an O(n2) sort such as bubble sort or insertion sort, it will take roughly n comparisons and exchanges to move this value all the way to the other end of the array. Shell sort first moves values using giant step sizes, so a small value will move a long way towards its final position, with just a few comparisons and exchanges.

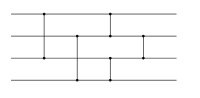

One can visualize Shell sort in the following way: arrange the list into a table and sort the columns (using an insertion sort). Repeat this process, each time with smaller number of longer columns. At the end, the table has only one column. While transforming the list into a table makes it easier to visualize, the algorithm itself does its sorting in-place (by incrementing the index by the step size, i.e. using i += step_size instead of i++).

For example, consider a list of numbers like [ 13 14 94 33 82 25 59 94 65 23 45 27 73 25 39 10 ]. If we started with a step-size of 5, we could visualize this as breaking the list of numbers into a table with 5 columns. This would look like this:

13 14 94 33 82 25 59 94 65 23 45 27 73 25 39 10

We then sort each column, which gives us

10 14 73 25 23 13 27 94 33 39 25 59 94 65 82 45

When read back as a single list of numbers, we get [ 10 14 73 25 23 13 27 94 33 39 25 59 94 65 82 45 ]. Here, the 10 which was all the way at the end, has moved all the way to the beginning. This list is then again sorted using a 3-gap sort, and then 1-gap sort (simple insertion sort).

[edit] Gap sequence

The gap sequence is an integral part of the Shell sort algorithm. Any increment sequence will work, as long as the last increment is 1. The algorithm begins by performing a gap insertion sort, with the gap being the first number in the gap sequence. It continues to perform a gap insertion sort for each number in the sequence, until it finishes with a gap of 1. When the gap is 1, the gap insertion sort is simply an ordinary insertion sort, guaranteeing that the final list is sorted.

The gap sequence that was originally suggested by Donald Shell was to begin with N / 2 and to halve the number until it reaches 1. While this sequence provides significant performance enhancements over the quadratic algorithms such as insertion sort, it can be changed slightly to further decrease the average and worst-case running times. Weiss' textbook[4] demonstrates that this sequence allows a worst case O(n2) sort, if the data is initially in the array as (small_1, large_1, small_2, large_2, ...) - that is, the upper half of the numbers are placed, in sorted order, in the even index locations and the lower end of the numbers are placed similarly in the odd indexed locations.

Perhaps the most crucial property of Shell sort is that the elements remain k-sorted even as the gap diminishes. For instance, if a list was 5-sorted and then 3-sorted, the list is now not only 3-sorted, but both 5- and 3-sorted. If this were not true, the algorithm would undo work that it had done in previous iterations, and would not achieve such a low running time.

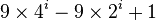

Depending on the choice of gap sequence, Shell sort has a proven worst-case running time of O(n2) (using Shell's increments that start with 1/2 the array size and divide by 2 each time), O(n3 / 2) (using Hibbard's increments of 2k − 1), O(n4 / 3) (using Sedgewick's increments of  , or

, or  ), or O(nlog2n) (using Pratt's increments 2i3j), and possibly unproven better running times. The existence of an O(nlogn) worst-case implementation of Shell sort was precluded by Poonen, Plaxton, and Suel[5].

), or O(nlog2n) (using Pratt's increments 2i3j), and possibly unproven better running times. The existence of an O(nlogn) worst-case implementation of Shell sort was precluded by Poonen, Plaxton, and Suel[5].

The best known sequence according to research by Marcin Ciura is 1, 4, 10, 23, 57, 132, 301, 701, 1750.[6] This study also concluded that "comparisons rather than moves should be considered the dominant operation in Shellsort."[7] A Shell sort using this sequence runs faster than an insertion sort or a heap sort, but even if it is faster than a quicksort for small arrays, it is slower for sufficiently big arrays. After 1750, gaps in geometric progression can be used, such as:

nextgap = round(gap * 2.3) //[citation needed]

Another sequence which performs empirically well is the Fibonacci numbers (leaving out one of the starting 1's) to the power of two times the golden ratio, which gives the following sequence: 1, 9, 34, 182, 836, 4025, 19001, 90358, 428481, 2034035, 9651787, 45806244, 217378076, 1031612713, ….[8]

[edit] Shell sort algorithm in pseudocode

input: an array a of length n

inc ← round(n/2)

while inc > 0 do:

for i = inc .. n − 1 do:

temp ← a[i]

j ← i

while j ≥ inc and a[j − inc] > temp do:

a[j] ← a[j − inc]

j ← j − inc

a[j] ← temp

inc ← round(inc / 2.2)

[edit] References

- ^ Shell, D.L. (1959). "A high-speed sorting procedure". Communications of the ACM 2 (7): 30–32. doi:.

- ^ "Shell sort". National Institute of Standards and Technology. http://www.nist.gov/dads/HTML/shellsort.html. Retrieved on 2007-07-17.

- ^ Pratt, V (1979). Shellsort and sorting networks (Outstanding dissertations in the computer sciences). Garland. ISBN 0-824-04406-1. (This was originally presented as the author's Ph.D. thesis, Stanford University, 1971)

- ^ Weiss, Mark Allen (2002). Data Structures & Problem Solving using Java. Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-201-74835-5.

- ^ Poonen, Plaxton, Suel (1992). "Improved Lower Bounds for Shellsort". Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (33): 226–235.

- ^ A102549 Best known gap sequence

- ^ Marcin Ciura, Best Increments for the Average Case of Shellsort, 13th International Symposium on Fundamentals of Computation Theory, Riga, Latvia, 22-24 August 2001; Lecture Notes in Computer Science 2001; Vol. 2138, pp. 106-117. [1]

- ^ A154393 The fibonacci to the power of two times the golden ratio gap sequence

[edit] External links

| The Wikibook Algorithm implementation has a page on the topic of |

- Detailed analysis of Shell sort

- Analysis of Shellsort and Related Algorithms, Robert Sedgewick

- Animated Sorting Algorithms: Shell Sort – graphical demonstration and discussion of Shell sort

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||