Operation Barbarossa

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Operation Barbarossa (German:Unternehmen Barbarossa) was the code name for Nazi Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II that commenced on 22 June 1941.[10][11] Over 4.5 million troops of the Axis powers invaded the USSR along a 2,900 kilometer front (1800 miles).[12] The operation was named after the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa of the Holy Roman Empire, a leader of the Third Crusade in the 12th century. The planning for Operation Barbarossa started on 18 December 1940; the secret preparations and the military operation itself lasted almost a year, from the spring of 1940, through the winter of 1941.

The operational goal of Barbarossa was the rapid conquest of the European part of the Soviet Union west of a line connecting the cities of Arkhangelsk and Astrakhan, often referred to as the A-A line (see the translation of Hitler's directive for details). At its conclusion in December 1941, the Red Army had repelled the strongest blow of the Wehrmacht. Hitler had not achieved the victory he had expected, but the situation of the Soviet Union remained critical. Tactically, the Germans had won some resounding victories and occupied some of the most important economic areas of the country, most notably in Ukraine.[13] Despite these successes, the Germans were pushed back from Moscow and were never able to mount an offensive simultaneously along the entire strategic Soviet-German front again.[14]

The failure of Operation Barbarossa resulted in Hitler's demands for additional operations inside the USSR, all of which eventually failed, such as continuation of the Siege of Leningrad,[15][16] Operation Nordlicht, and Battle of Stalingrad, among other battles on the occupied Soviet territory.[17][18][19][20][21]

Operation Barbarossa remains the largest military operation, in terms of manpower, area traversed, and casualties, in human history.[22] Its failure is considered a turning point in the fortunes of the Third Reich. Most importantly, Operation Barbarossa opened up the Eastern Front, which ultimately became the biggest theater of war in world history. Operation Barbarossa and the areas which fell under it became the site of some of the largest battles, deadliest atrocities, terrible loss of life, and horrific conditions for Soviets and Germans alike - all of which influenced the course of both World War II and the 20th century history.

Contents |

[edit] German intentions

[edit] Nazi theory regarding the Soviet Union

As early as 1925, Hitler made his intentions clear in Mein Kampf ("My Struggle") to invade the Soviet Union, based on his assertion that the German people needed Lebensraum ("living space", i.e. land and raw materials) and that it should be sought in the east. Nazi racial ideology cast the Soviet Union as populated by "untermenschen" ethnic Slavs ruled by their "Jewish Bolshevik" masters.[23][24] Mein Kampf stated that Germany's destiny was to turn "to the East" as it did "six hundred years later" and "the end of the Jewish domination in Russia will also be the end of Russia as a State."[25] Thereafter, Hitler spoke of an inescapable battle against "pan-Slav ideals", the victory in which would lead to "permanent mastery of the world", though he stated that they would "walk part of the road with the Russians, if that will help us."[26] Accordingly, it was the stated policy of the Nazis to kill, deport or enslave the Russian and other Slavic populations and to repopulate the land with Germanic peoples (see New Order).

[edit] 1939-1940 Nazi-Soviet relations

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact had been signed shortly before the German and Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939. It was ostensibly a non-aggression pact but secret protocols outlined an agreement between the Third Reich and the Soviet Union on the division of the border states between them.[27] The pact surprised the world,[28] because of their mutual hostility and their opposed ideologies. As a result of the pact, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union had reasonably strong diplomatic relations and engaged in an important economic and trading relationship. The countries entered a German-Soviet trade pact, pursuant to which the Soviets received German military and industrial equipment in exchange for supplying raw materials, such as oil, to Germany to help circumvent a British blockade.[29]

But despite the parties' ongoing relations, both sides remained strongly suspicious of each others' intentions. After Germany entered the Axis Pact with Japan and Italy, it initiated negotiations regarding the potential Soviet entry into the pact.[30][31] After two days of negotiations in Berlin from November 12-14, Germany presented a proposed written agreement for Soviet entry into the Axis, the Soviet Union presented a written counterproposal agreement on November 25, 1940, to which Germany did not respond.[32][33] As both sides began colliding with each other in Eastern Europe, conflict appeared more likely, though they signed a border and commercial agreement addressing several open issues in January 1941.

[edit] Germany plans the invasion

Stalin's reputation contributed both to the Nazis' justification of their assault and to their faith in success. During the late 1930s, Stalin had killed or incarcerated millions of citizens during the Great Purge, including large numbers of competent and experienced military officers, leaving the Red Army weakened and leaderless. The Nazis often emphasized the brutality of the Soviet regime when targeting the Slavs with propaganda. German propaganda made claims that the Red Army was preparing to attack them, and their own invasion was thus presented as being pre-emptive.

During the summer of 1940, when German raw materials crises and a potential collision with the Soviet Union over territory in the Balkans arose, an eventual invasion of the Soviet Union increasingly looked like the only solution for Hitler.[34] While no concrete plans were yet made, Hitler told one of his generals in June that the victories in western Europe "finally freed his hands for his important real task: the showdown with Bolshevism",[35] though German generals told Hitler that occupying Western Russia would create "more of a drain than a relief for Germany's economic situation."[36] The Führer anticipated additional benefits:

- When the Soviet Union was defeated, the labour shortage in the German industry could be ended by the demobilization of many soldiers.

- Ukraine would be a reliable source of agriculture.

- Having the Soviet Union as a source of slave labour would vastly improve Germany's geostrategic position.

- Defeat of the Soviet Union would further isolate the Allies, especially the United Kingdom.

- The German economy needed access to more oil and controlling the Baku Oilfields would achieve this.

On December 5, Hitler received military plans for the possible invasion, and approved them all, with the invasion scheduled for May 1941.[37] On December 18, 1940, Hitler signed War Directive No. 21 to the German high command for an operation now codenamed "Operation Barbarossa" stating: "The German Wermacht must be prepared to crush Soviet Russia in a quick campaign."[38][37] The date for the invasion was set for May 15, 1941.[38] In the Soviet Union, speaking to his generals in December, Stalin references Hitler's references to a Soviet attack in Mein Kampf, stated that they must always be ready to repulse a German attack, stated that Hitler thought that the Red Army would require four years to ready itself such that "we must be ready much earlier" and "we will try to delay the war for another two years."[39]

In the fall of 1940, High ranking German officials drafted a memorandum on the dangers of a Soviet invasion, including that the Ukraine, Belorussia and the Baltic States would end up only being a further economic burden for Germany.[40] Another German official argued that the Soviets in their current bureaucratic form were harmless, the occupation would not produce a gain for Germany and "why should it not stew next to us in its damp Bolshevism?"[40] Hitler ignored German economic naysayers, and told Herman Goering that "that everyone on all sides was always raising economic misgivings against a threatening war with Russia. From now onwards he wasn't going to listen to any more of that kind of talk and from now on he was going to stop up his ears in order to get his peace of mind."[41] This was passed on to General Georg Thomas, who had been preparing reports on the negative economic consequences of a Soviet invasion -- that it would be a net economic drain unless it was captured intact. [41]

Beginning in March 1941, Goering's Green Folder laid out the details of the proposed economic subsection of the Soviet Union after the invasion. The entire urban population of the invaded land was to be eradicated through starvation, thus creating an agricultural surplus to feed Germany and allowing the urban population's replacement by a German upper class. During the Nuremberg Trials in 1946, Sir Hartley Shawcross announced that in March 1941, in addition to administrative divisions previously created, the following divisions in the Russian East were planned:

- Ural (central and south Ural and nearest territories, created from planned east Russian European territorial reorganization)

- West Sibirien (future west Siberia and Novosibirsk held lands)

- Nordland (Soviet Arctic areas: West Nordland (Russian European north coasts) and Ost Nordland (northwest Siberian north coasts))

In the summer of 1941, German Nazi-ideologist Alfred Rosenberg suggested that conquered Soviet territory should be administered in the following Reichskommissariates:

- Ostland (The Baltic countries and Belarus)

- Ukraine (Ukraine and adjacent territories)

- Kaukasus (Southern Russia and the Caucasus area)

- Moskau (Moscow metropolitan area and the rest of European Russia)

- Turkestan (Central Asian republics and territories)

Nazi policy aimed to destroy the Soviet Union as a political entity in accordance with the geopolitical Lebensraum idea ("Drang nach Osten") for the benefit of future "Aryan" generations in the centuries to come.

| “ | We have only to kick in the door and the whole rotten structure will come crashing down | ” |

|

—Adolf Hitler |

||

Operation Barbarossa was to combine a northern assault towards Leningrad, a symbolic capturing of Moscow, and an economic strategy of seizing oil fields in the south, beyond Ukraine. Hitler and his generals disagreed on which of these aspects should take priority and where Germany should focus its energies; deciding upon priorities required a compromise. Hitler considered himself a political and military genius. In the course of planning Barbarossa during 1940 and 1941, in many discussions with his generals, Hitler repeated his order: "Leningrad first, the Donetsk Basin second, Moscow third."[10][42] Hitler was impatient to get on with his long-desired invasion of the east. He was convinced that Britain would sue for peace, once the Germans triumphed in the Soviet Union, the real area of Germany's interests. General Franz Halder noted in his diaries that, by destroying the Soviet Union, Germany would destroy Britain's hope of defeating Germany.

Hitler had become over-confident, owing to his rapid success in Western Europe, as well as the Red Army's ineptitude in the Winter War against Finland in 1939–40. He expected victory within a few months and therefore did not prepare for a war lasting into the winter. His troops therefore lacked adequate warm clothing and preparations for a longer campaign when they began their attack. The assumption that the Soviet Union would quickly capitulate would prove to be his undoing.[43]

[edit] German preparations

| “ | When Barbarossa commences, the world will hold its breath and make no comment. | ” |

|

—Adolf Hitler |

||

In preparation for the attack, Hitler moved 3.5 million German soldiers and about 1 million Axis soldiers to the Soviet border, launched many aerial surveillance missions over Soviet territory, and stockpiled materiel in the East. The Soviets were still taken by surprise, mostly due to Stalin's belief that the Third Reich was unlikely to attack only two years after signing the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The Soviet leader also believed that the Nazis would likely finish their war with Britain before opening a new front. He refused to believe repeated warnings from his intelligence services on the Nazi buildup, fearing the reports to be British misinformation designed to spark a war between Germany and the USSR. The spy Dr. Richard Sorge gave Stalin the exact German launch date; Swedish cryptanalysts led by Arne Beurling also knew the date beforehand.

The Germans set up deception operations, from April 1941, to add substance to their claims that Britain was the real target: Operations Haifisch and Harpune. These simulated preparations in Norway, the Channel coast and Britain. There were supporting activities such as ship concentrations, reconnaissance flights and training exercises. Invasion plans were developed and some details were allowed to leak.

Hitler and his generals also researched Napoleon's failed invasion of Russia. At Hitler's insistence, the German High Command (OKW) began to develop a strategy to avoid repeating these mistakes.[citation needed]

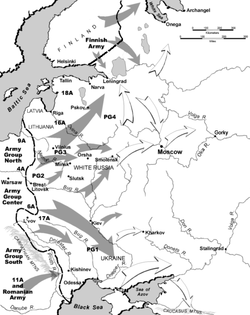

The strategy Hitler and his generals agreed upon involved three separate army groups assigned to capture specific regions and cities of the Soviet Union. The main German thrusts were conducted along historical invasion routes. Army Group North was assigned to march through the Baltics, into northern Russia, and either take or destroy the city of Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg). Army Group Center would advance to Smolensk and then Moscow, marching through what is now Belarus and the west-central regions of Russia proper. Army Group South was to strike the heavily populated and agricultural heartland of Ukraine, taking Kiev before continuing eastward over the steppes of the southern USSR all the way to the Volga and the oil-rich Caucasus.

Hitler, the OKW and the various high commands disagreed about what the main objectives should be. In the preparation for Barbarossa, most of the OKW argued for a straight thrust to Moscow, whereas Hitler kept asserting his intention to seize the resource-rich Ukraine and Baltics before concentrating on Moscow. An initial delay, which postponed the start of Barbarossa from mid-May to the end of June 1941, may have been insignificant, especially since the Russian muddy season came late that year. However, more time was lost at various critical moments as Hitler and the OKW suspended operations in order to argue about strategic objectives.

Along with the strategic objectives, the Germans also decided to bring rear forces (mostly Waffen-SS units and Einsatzgruppen) into the conquered territories to counter any partisan activity which they knew would erupt in the areas they controlled.[citation needed]

[edit] Soviet preparations

Despite the estimation by Hitler and others in the German high command, the Soviet Union was by no means a weak country. Rapid industrialization in the 1930s had resulted in industrial output second only to that of the United States, and equal to that of Germany. Production of military equipment grew steadily, and in the pre-war years the economy became progressively more oriented toward military production. In the early 1930s, a very modern operational doctrine for the Red Army was developed and promulgated in the 1936 field regulations.

| 1 January 1939 | 22 June 1941 | % increase | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Divisions calculated | 131.5 | 316.5 | 140.7 |

| Personnel | 2,485,000 | 5,774,000 | 132.4 |

| Guns and mortars | 55,800 | 117,600 | 110.7 |

| Tanks | 21,100 | 25,700 | 21.8 |

| Aircraft | 7,700 | 18,700 | 142.8 |

According to Taylor ands Proektor (1974), the Soviet armed forces in the western districts were outnumbered by their German counterparts, 2.6 million Soviet soldiers vs. 4.5 million for the Axis. The overall size of the Soviet armed forces in early July 1941, though, amounted to a little more than 5 million men, 2.6 million in the west, 1.8 million in the far east, with the rest being deployed or training elsewhere.[45] These figures, however, can be misleading.[citation needed] The figure for Soviet strength in the western districts of the Soviet Union counts only the First Strategic Echelon, which was stationed on and behind the Soviet western frontier to a depth of 400 kilometres; it also underestimates the size of the First Strategic Echelon, which was actually 2.9 million strong.[citation needed] The figure does not include the smaller Second Strategic Echelon, which as of 22 June 1941 was in process of moving toward the frontier; according to the Soviet strategic plan, it was scheduled to be in position reinforcing the First Strategic Echelon by early July. The total Axis strength is also exaggerated; 3.3 million German troops were earmarked for participation in Barbarossa, but that figure includes reserves which did not take part in the initial assault. A further 600,000 troops provided by Germany's allies also participated, but mostly after the initial assault.

Total Axis forces available for Barbarossa were therefore in the order of 3.9 million. On 22 June, the German Wehrmacht was able to achieve a local superiority in its initial assault (98 German divisions), including 29 armoured and motorized divisions, some 90% of its mobile forces, attacking on a front of 1,200 kilometres between the Baltic Sea and the Carpathian Mountains, against NKVD border troops and the divisions of the Soviet First Operational Echelon (the part of the First Strategic Echelon stationed immediately behind the frontier) in the three western Special Military Districts) because it had completed its deployment and was ready to attack about two weeks before the Red Army was scheduled to have completed its own deployment with the Second Strategic Echelon in place. At the time, 41% of stationary Soviet bases were located in the near-boundary districts, many of them in the 200 km strip around the border; according to Red Army directive, fuel, equipment railroad cars etc. were similarly concentrated there.[46]

Moreover, on mobilization, as the war went on, the Red Army gained steadily in strength. While the strength of both sides varied, in general it is accurate to say that the 1941 campaign was fought with the Axis having slight numerical superiority in manpower at the front. According to Mikhail Meltyukhov (2000:477), by the beginning of war, Red Army numbered altogether 5,774,211 troops: 4,605,321 in ground forces, 475,656 in air forces, 353,752 in the navy, 167,582 as border guards and 171,900 in internal troops of the NKVD.

In some key weapons systems, however, the Soviet numerical advantage was considerable. In tanks, for example, the Red Army had a large superiority. It possessed 23,106 tanks,[47] of which about 12,782 were in the five Western Military Districts (three of which directly faced the German invasion front). However, maintenance and readiness standards were very poor; ammunition and radios were in short supply, and many units lacked the trucks needed for resupply beyond their basic fuel and ammunition loads.

Also, from 1938, the Soviets had partly dispersed their tanks to infantry divisions for infantry support, but after their experiences in the Winter War and their observation of German Blitzkrieg tactics against France, had begun to emulate the Germans and organize most of their armoured assets into large, fully mechanized divisions and corps. This reorganization however was only partially implemented at the dawn of Barbarossa,[48] as not enough tanks were available to bring the mechanised corps up to organic strength.

The German Wehrmacht had about 5,200 tanks overall, of which 3,350 were committed to the invasion. This yields a balance of immediately-available tanks of approximately 4:1 in the Red Army's favor. The best Soviet tank, the T-34, was the most modern in the world, and the KV series the best armoured. The most advanced Soviet tank models, however, the T-34 and KV-1, were not available in large numbers early in the war, and only accounted for 7.2% of the total Soviet tank force. But while these 1,861 modern tanks were technically superior to the 1,404 German medium Panzer III and IV tanks, the Soviets in 1941 still lacked the communications, training and experience to employ such weapons effectively.

The Soviet numerical advantage in heavy equipment was also more than offset by the greatly superior training and readiness of German forces. The Soviet officer corps and high command had been decimated by Stalin's Great Purge (1936–1938). Of 90 generals arrested, only six survived the purges, as did only 36 of 180 divisional commanders, and just seven out of 57 army corps commanders. In total, some 30,000 Red Army personnel were executed,[49] while more were shipped to Siberia and replaced with officers deemed more "politically reliable." Three of the five pre-war marshals and about two thirds of the corps and division commanders were shot. This often left younger, less experienced officers in their places; for example, in 1941, 75% of Red Army officers had held their posts for less than one year. The average Soviet corps commander was 12 years younger than the average German division commander. These officers tended to be very reluctant to take the initiative and often lacked the training necessary for their jobs.

The number of aircraft was also heavily in the Soviets' favor. However, Soviet aircraft were largely obsolete, and Soviet artillery lacked modern fire control techniques.[50] Most Soviet units were on a peacetime footing, explaining why aviation units had their aircraft parked in closely-bunched neat rows, rather than dispersed, making easy targets for the Luftwaffe in the first days of the conflict. Prior to the invasion the VVS was forbidden to shoot down Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft, despite hundreds of pre-war flights into Soviet airspace.

The Soviet war effort in the first phase of the Eastern front war was severely hampered by a shortage of modern aircraft. The Soviet fighter force was equipped with large numbers of obsolete aircraft, such as the I-15 biplane and the I-16. In 1941, the MiG-3, LaGG-3 and Yak-1 were just starting to roll off the production lines, but were far inferior in all-round performance to the Messerschmitt Bf 109 or later, the Fw 190, when it entered operations in September 1941. Few aircraft had radios and those that were available were unencrypted and did not work reliably. The poor performance of VVS (Voenno-Vozdushnye Sily, Soviet Air Force) during the Winter War with Finland had increased the Luftwaffe's confidence that the Soviets could be mastered. The standard of flight training had been accelerated in preparation for a German attack that was expected to come in 1942 or later. But Soviet pilot training was extremely poor. Order No 0362 of the People's Commissar of Defense, dated December 22, 1940, ordered flight training to be accelerated and shortened. Incredibly, while the Soviets had 201 MiG-3s and 37 MiG-1s combat ready on 22 June 1941, only four pilots had been trained to handle these machines.[51]

The Red Army was dispersed and unprepared, and units were often separated and without transportation to concentrate prior to combat. Although the Red Army had numerous, well-designed artillery pieces, some of the guns had no ammunition. Artillery units often lacked transportation to move their guns. Tank units were rarely well-equipped, and also lacked training and logistical support. Maintenance standards were very poor. Units were sent into combat with no arrangements for refueling, ammunition resupply, or personnel replacement. Often, after a single engagement, units were destroyed or rendered ineffective. The army was in the midst of reorganizing the armor units into large tank corps, adding to the disorganization.

As a result, although on paper the Red Army in 1941 seemed at least the equal of the German army, the reality in the field was far different; incompetent officers, as well as partial lack of equipment, insufficient motorised logistical support, and poor training placed the Red Army at a severe disadvantage. For example, throughout the early part of the campaign, the Red Army lost about six tanks for every German tank lost.

In the spring of 1941, Stalin's own intelligence services made regular and repeated warnings of an impending German attack. However, Stalin chose to ignore these warnings. Although acknowledging the possibility of an attack in general and making significant preparations, he decided not to run the risk of provoking Hitler. He had fielded officers who were likely indeed to tell him only what he wanted to hear, so that he believed that the position of the Soviet Union in early 1941 was much stronger than it actually was.[citation needed] He also had an ill-founded confidence in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which had been signed just two years before. Last, he also suspected the British of trying to spread false rumours in order to trigger a war between Germany and the USSR.[52][53] Consequently, the Soviet border troops were not put on full alert and were sometimes even forbidden to fire back without permission when attacked — though a partial alert was implemented on April 10 — they were simply not ready when the German attack came. This may be the source of the argument cited below by Viktor Suvorov.

Enormous Soviet forces were massed behind the western border in case the Germans did attack. However, these forces were very vulnerable due to changes in the tactical doctrine of the Red Army. In 1938 it had adopted, on the instigation of General Pavlov, a standard linear defence tactic on a line with other nations. Infantry divisions, reinforced by an organic tank component, would be dug in to form heavily fortified zones. Then came the shock of the Fall of France. The French Army, considered the strongest in the world[citation needed], was defeated in a mere six weeks. Soviet analysis of events, based on incomplete information, concluded that the collapse of the French was caused by a reliance on linear defence and a lack of armoured reserves.

The Soviets decided not to repeat these mistakes. Instead of digging in for linear defence, the infantry divisions would henceforth be concentrated in large formations.[54] Most tanks would also be concentrated into 31 mechanised corps, each with over 1000 tanks - larger than an entire German panzer army (though only a few such corps had attained their nominal strength by June 22).[citation needed] Should the Germans attack, their armoured spearheads would be cut off and wiped out by the mechanised corps.[citation needed] These would then cooperate with the infantry armies to drive back the German infantry, vulnerable in its approach march. The Soviet left wing, in Ukraine, was to be enormously reinforced to be able to execute a strategic envelopment: after destroying German Army Group South, it would swing north through Poland in the back of Army Groups Centre and North. With the complete annihilation of the encircled German Army thus made inevitable, a Red Army offensive into the rest of Europe would follow.[55][56]

[edit] The Soviet offensive plans theory

Counter-arguments to the usual interpretation have been advanced by former GRU defector Viktor Suvorov, author of Icebreaker. This book argues that Soviet ground forces were extremely well organized, and were mobilizing en masse all along the German-Soviet border for a Soviet invasion of Europe slated for Sunday July 6, 1941. The German Barbarossa, he claims, actually was a pre-emptive strike that capitalized on the massive Soviet troop concentrations immediately on the 1941 Nazi Germany's borders. Suvorov argues therefore that Soviet troop concentrations on Germany's borders were offensive in nature, not defensive as usually described. His interpretation has been thoroughly rejected by various respected historians, in particular David Glantz, and has not found much serious support among Western academic historians.

A study by Russian military historian Mikhail Meltyukhov (“Stalin's Missed Chance”) supports the claim that Soviet forces were concentrating in order to attack Germany. However, he rejects the statement that the German invasion was a pre-emptive strike: Meltyukhov believes both sides were preparing for the assault but neither believed in the possibility of an attack by the other side. Other Russian historians who support this thesis are Vladimir Nevezhin, Boris Sokolov and Valeri Danilov. In key points this argumentation resembles the interpretation of German historians Werner Maser and Joachim Hoffmann.[57]

The now published Zhukov proposal of May 15, 1941[58] called for a Soviet strike against Germany. Thus the document suggested secret mobilisation and deploying Red Army troops next to the Western border, under the cover of training. Although generally believed to be a mere draft disapproved of by Stalin,[59] the above mentioned historians have argued, that — given Stalin's concentration of power — the thesis of Soviet generals pursuing a line independent of Stalin's and composing an invasion plan must have been extremely improbable. Moreover, it is argued that the actual Soviet troops concentration was near the border, just like fuel depots and airfields. All of this was unsuitable for defensive operations. (Maser 1994: 376–378; Hoffmann 1999: 52–56)

Suvorov presents a piece of evidence favoring the theory of an impending Soviet attack: the maps and phrasebooks issued to Soviet troops. Military topographic maps, unlike other military supplies, are strictly local and cannot be used elsewhere than in the intended target. According to Suvorov, Soviets were issued with maps of Germany and German-occupied territory, and phrasebooks including questions about SA offices — SA offices were found only in German territory proper. In contrast, according to Suvorov, maps of Soviet territory were scarce. Notably, after the German attack, the officer responsible for maps, Lieutenant General M.K. Kudryavtsev was not punished by Stalin, who was known for extreme punishments after failures to obey his orders. According to Suvorov, this demonstrates that General Kudryavtsev was obeying the orders of Stalin, who simply did not expect a German attack.

However, none of this is conclusive evidence of Soviet plans for a strategic attack on Germany, especially since Soviet doctrine emphasized the offensive at the operational level, even if the country was strategically on the defensive.

| Germany and Allies | Soviet Union | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Divisions | 166 | 190 | 1 : 1.1 |

| Personnel | 4,306,800 | 3,289,851 | 1.3 : 1 |

| Guns and mortars | 42,601 | 59,787 | 1 : 1.4 |

| Tanks (incl assault guns) | 4,171 | 15,687 | 1 : 3.8 |

| Aircraft | 4,389[60] | 11, 537[61] | 1 : 2.6 |

[edit] The invasion

[edit] Composition of the Axis forces

Halder as the Chief of General Staff OKH concentrated the following Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe forces for the operation:

Army Group North (Heeresgruppe Nord) (Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb) staged in East Prussia with (26 divisions):

- 16th Army (16. Armee) (Ernst Busch)

- 4th Panzer Group (Panzergruppe 4) (Hoepner)

- 18th Army (18. Armee) (Georg von Küchler)

- Air Fleet 1 (Luftflotte eins) (Alfred Keller)

Army Group Centre (Heeresgruppe Mitte) (Fedor von Bock) staged in Eastern Poland with (49 divisions):

- 4th Army (4. Armee) (Günther von Kluge)

- 2nd Panzer Group (Panzergruppe 2) (Guderian)

- 3rd Panzer Group (Panzergruppe 3) (Hermann Hoth)

- 9th Army (9. Armee) (Strauss)

- Air Fleet 2 (Luftflotte zwei) (Albert Kesselring)

Army Group South (Heeresgruppe Süd) (Gerd von Rundstedt) was staged in Southern Poland and Romania with (41 divisions):

- 17th Army (17. Armee) (Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel)

- Slovak Expeditionary Force (Čatloš)

- Royal Hungarian Army "Fast Moving Army Corps"(Miklós) - Initially part of a larger "Karpat Group" (Karpat Gruppe)

- 1st Panzer Group (Panzergruppe 1) (von Kleist)

- 11th Army (Eugen Ritter von Schobert)

- Italian Expeditionary Corps in Russia (Corpo di Spedizione Italiano in Russia, CSIR) (Messe)

- 6th Army (6. Armee) (Walther von Reichenau)

- Air Fleet 4 (Luftflotte vier) (Alexander Löhr)

Staged from Norway a smaller group of forces consisted of:

- Army High Command Norway (Armee-Oberkommando Norwegen) (Nikolaus von Falkenhorst) with two Corps

- Air Fleet 5 (Luftflotte funf) (Stumpff)

Numerous smaller units from all over Nazi-occupied Europe, like the "Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism" (Légion des Volontaires Français contre le Bolchévisme), supported the German war effort.

[edit] Composition of the Soviet Forces

At the beginning of the German Reich’s invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941 the Red Army areas of responsibility in the European USSR were divided into four active Fronts. More Fronts would be formed within the overall responsibility of the three Strategic Directions commands which corresponded approximately to a German Army (Wehrmacht Heer) Army Group (Heeresgruppen) in terms of geographic area of operations.

On Zhukov's orders immediately following the invasion[citation needed] the Northern Front was formed from the Leningrad Military District, the North-Western Front from the Baltic Special Military District, the Western Front was formed from the Western Special Military District, and the Soviet Southwestern Front was formed from the Kiev Special Military District. The Southern Front was created on the June 25, 1941 from the Odessa Military District.

The first Directions were established on 10 July 1941, with Voroshilov commanding the North-Western Strategic Direction, Timoshenko commanding the Western Strategic Direction, and Budyonny commanding the South-Western Strategic Direction.[63]

The forces of the North-Western Direction were:[64]

- The Northern Front was commanded by Colonel General Markian Michailovitch Popov bordered Finland and included the 14th Army, 7th Army, and the 23rd Army as well as smaller units subordinate to the Front commander.

- The North-Western Front was commanded by Colonel General Fyodor Kuznetsov defended the Baltic region and consisted of the 8th Army, 11th Army, and the 27th Army and other front troops(34 divisions).

- The Northern and Baltic Fleets

The forces of the Western Direction were:

- The Western Front, commanded by General Dmitry Grigoryevitch Pavlov, had the 3rd Army, 4th Army, 10th Army and the Army Headquarters of the 13th Army which coordinated independent Front formations(45 divisions).[citation needed]

- The Pinsk Flotilla

The forces of the South-Western Direction consisted of:

- The South-Western Front was commanded by Colonel General Mikhail Petrovitch Kirponos was formed from the 5th Army, 6th Army, 12th Army and the 26th Army as well as a group of units under Strategic Direction command(45 divisions).

- The Southern Front was commanded by General Ivan Vladimirovitch Tyulenev created on the June 25, 1941 from the 9th Independent Army and the 18th Army with 2nd and 18th Mechanized Corps in support(26 divisions).

- The Black Sea Fleet

Beside the Armies in the Fronts, there were a further six armies in the Western region of the USSR: 16th Army, 19th Army, 20th Army, 21st Army, 22nd Army and the 24th Army which formed, together with independent units, the Stavka Reserve Group of Armies which was later renamed the Reserve Front nominally under Stalin's direct command.

[edit] Opening phase (22 June 1941 - 3 July 1941)

At 3:15 am on Sunday, 22 June 1941, the Axis attacked. It is difficult to precisely pinpoint the strength of the opposing sides in this initial phase, as most German figures include reserves slated for the East but not yet committed, as well as several other issues of comparability between the German and USSR's figures. A reasonable estimate is that roughly three million Wehrmacht troops went into action on June 22, and that they were facing slightly fewer Soviet troops in the border Military Districts. The contribution of the German allies would generally only begin to make itself felt later in the campaign. The surprise was complete: though the Stavka, alarmed by reports that Wehrmacht units were approaching the border, had at 00:30 AM ordered that the border troops be warned that war was imminent, only a small number of units were alerted in time.

The shock stemmed less from the timing of the attack than from the sheer number of Axis troops who struck into Soviet territory simultaneously.[citation needed] Aside from the roughly 3.2 million German ground troops engaged in, or earmarked for the Eastern Campaign, about 500,000 Romanian, Hungarian, Slovakian, Croatian, and Italian troops eventually accompanied the German forces, while the Army of Finland made a major contribution in the north. The 250th Spanish "Blue" Infantry Division was a formation of Spanish Falangists and Nazi sympathisers.

Reconnaissance units of the Luftwaffe worked at a frantic pace to plot troop concentration, supply dumps, and airfields, and mark them[citation needed] for destruction. The task of the Luftwaffe was to neutralise the Soviet Air Force. This was not achieved in the first days of operations, despite the Soviets having concentrated aircraft in huge groups on the permanent airfields rather than dispersing them on field landing strips, making them ideal targets. The Luftwaffe claimed to have destroyed 1,489 aircraft on the first day of operations.[65] Hermann Göring, Chief of the Luftwaffe distrusted the reports and ordered the figure checked. Picking through the wreckages of Soviet airfields, the Luftwaffe's figures proved conservative, as over 2,000 destroyed Soviet aircraft were found.[65] The Germans claimed to have destroyed only 3,100 Soviet aircraft in the first three days. In fact the Soviet losses were far higher, some 3,922 Soviet machines had been lost (according to Russian Historian Viktor Kulikov).[66] The Luftwaffe had achieved air superiority over all three sectors of the front, and would maintain it until the close of the year, largely due to the need by the Red Army Air Forces to manoeuvre in support of retreating ground troops.[citation needed] The Luftwaffe would now be able to devote large numbers of its Geschwader (See Luftwaffe Organization) to support the ground forces.

[edit] Army Group North

Opposite Heersgruppe Nord were two Soviet armies. The Wehrmacht OKH thrust the 4th Panzer Group, with a strength of 600 tanks, at the junction of the two Soviet armies in that sector. The 4th Panzer Group's objective was to cross the rivers Neman and Daugava (Dvina) which were the two largest obstacles in the direction of advance towards Leningrad. On the first day, the tanks crossed the River Neman and penetrated 50 miles (80 km). Near Raseiniai, the tanks were counterattacked by 300 Soviet tanks. It took four days for the Germans to encircle and destroy the Soviet armour. The Panzer Groups then crossed the Daugava near Daugavpils. The Germans were now within striking distance of Leningrad. However, due to their deteriorated supply situation, Hitler ordered the Panzer Groups to hold their position while the infantry formations caught up. The orders to hold would last over a week, giving time for the Soviets to build up a defence around Leningrad and along the bank of River Luga. Further complicating the Soviet position, on 22 June the anti-Soviet June Uprising in Lithuania began, and on the next day an independent Lithuania was proclaimed.[67] An estimated 30,000 Lithuanian rebels engaged Soviet forces, joined by ethnic Lithuanians from the Red Army. As the Germans reached further north, armed resistance against the Soviets broke out in Estonia as well. The "Battle of Estonia" ended on 7 August, when the 18.Armee reached the coast at Kunda.[68]

[edit] Army Group Centre

Opposite Heersgruppe Mitte were four Soviet armies: the 3rd, 4th, 10th and 11th Armies. The Soviet Armies occupied a salient which jutted into German occupied Polish territory with the Soviet salient's center at Bialystok. Beyond Bialystok was Minsk, both the capital of Belorussia and a key railway junction. The goals of the AG Centre's two Panzer Groups was to meet at Minsk, denying an escape route to the Red Army from the salient. The 3rd Panzer Group broke through the junction of two Soviet Fronts in the North of the salient, and crossed the River Neman while the 2nd Panzer Group crossed the Western Bug river in the South. While the Panzer Groups attacked, the Wehrmacht Army Group Centre infantry Armies struck at the salient, eventually encircling Soviet troops at Bialystok.

Moscow at first failed to grasp the dimensions of the catastrophe that had befallen the USSR. Marshall Timoshenko ordered all Soviet forces to launch a general counter-offensive, but with supply and ammunition dumps destroyed, and a complete collapse of communication, the uncoordinated attacks failed. Zhukov signed the infamous Directive of People's Commissariat of Defence No. 3 (he later claimed under pressure from Stalin), which demanded that the Red Army start an offensive: he commanded the troops “to encircle and destroy the enemy grouping near Suwałki and to seize the Suwałki region by the evening of June 26" and “to encircle and destroy the enemy grouping invading in Vladimir-Volynia and Brody direction” and even “to seize the Lublin region by the evening of 24.6”[69] This manoeuvre failed and disorganised Red Army units, which were soon destroyed by the Wehrmacht forces.

On 27 June 2nd and 3rd Panzer Groups met up at Minsk advancing 200 miles (300 km) into Soviet territory and a third of the way to Moscow. In the vast pocket between Minsk and the Polish border, the remnants of 32 Soviet Rifle, eight tank, and motorized, cavalry and artillery divisions were encircled.

[edit] Army Group South

Opposite Heersgruppe Süd in Ukraine Soviet commanders had reacted quickly to the German attack. From the start, the invaders faced a determined resistance. Opposite the Germans in Ukraine were three Soviet armies, the 5th, 6th and 26th. The German infantry Armies struck at the junctions of these armies while the 1st Panzer Group drove its armored spearhead of 600 tanks right through the Soviet 6th Army with the objective of capturing Brody. On 26 June five Soviet mechanized corps with over 1,000 tanks mounted a massive counter-attack on the 1st Panzer Group. The battle was among the fiercest of the invasion, lasting over four days; in the end the Germans prevailed, though the Soviets inflicted heavy losses on the 1st Panzer Group.

With the failure of the Soviet counter-offensives, the last substantial Soviet tank forces in Western Ukraine had been committed, and the Red Army assumed a defensive posture, focusing on conducting a strategic withdrawal under severe pressure. By the end of the first week, all three German Army Groups had achieved major campaign objectives. However, in the vast pocket around Minsk and Bialystok, the Soviets were still fighting; reducing the pocket was causing high German casualties and many Red Army troops were also managing to escape. The usual estimated casualties of the Red Army amount to 600,000 killed, missing, captured or wounded. The Soviet air arm, the VVS, lost 1,561 aircraft over Kiev.[70] The battle was a huge tactical (Hitler thought strategic) victory, but it had succeeded in drawing German forces, away from an early offensive against Moscow, and had delayed further German progress by 11 weeks. General Kurt Von Tippleskirch noted, "The Russians had indeed lost a battle, but they won the campaign".[70]

[edit] Middle phase (3 July 1941 - 2 October 1941)

On 3 July Hitler finally gave the go-ahead for the Panzers to resume their drive east after the infantry divisions had caught up. However, a rainstorm typical of Russian summers slowed their progress and Russian defences also stiffened. The delays gave the Soviets time to organize for a massive counterattack against Army Group Centre. The ultimate objective of Army Group Centre was the city of Smolensk, which commanded the road to Moscow. Facing the Germans was an old Soviet defensive line held by six armies. On 6 July the Soviets launched an attack with 700 tanks against the 3rd Panzer Army. The Germans defeated this counterattack using their overwhelming air superiority. The 2nd Panzer Army crossed the River Dnieper and closed on Smolensk from the south while the 3rd Panzer Army, after defeating the Soviet counter attack, closed in Smolensk from the north. Trapped between their pincers were three Soviet armies. On 26 July the Panzer Groups closed the gap and 180,000 Red Army troops were captured.[71]

Four weeks into the campaign, the Germans realized they had grossly underestimated the strength of the Soviets. The German troops had run out of their initial supplies but still not attained the expected strategic freedom of movement. Operations were now slowed down to allow for a resupply; the delay was to be used to adapt the strategy to the new situation. Hitler had lost faith in battles of encirclement as large numbers of Soviet soldiers had continued to escape them and now believed he could defeat the Soviets by inflicting severe economic damage, depriving them from the industrial capacity to continue the war. That meant the seizure of the industrial center of Kharkov, the Donets Basin and the oil fields of the Caucasus in the south and a speedy capture of Leningrad, a major center of military production, in the north. He also wanted to link up with the Finns to the north.

The German generals vehemently argued instead for continuing the all-out drive toward Moscow. Besides the psychological importance of capturing the enemy's capital, the generals pointed out that Moscow was a major center of arms production and the center of the Soviet communications and transportation system. More importantly, intelligence reports indicated that the bulk of the Red Army was deployed near Moscow under Semyon Timoshenko for an all-out defense of the capital. However, Hitler was adamant, and issued an order to send Army Group Centre's tanks to the north and south, temporarily halting the drive to Moscow. By mid-July below the Pinsk Marshes, the Germans had come within a few kilometers of Kiev. The 1st Panzer Army then went south while the German 17th Army struck east and in between the Germans trapped three Soviet armies near Uman. As the Germans eliminated the pocket, the tanks turned north and crossed the Dnieper. Meanwhile, the 2nd Panzer Army, diverted from Army Group Centre, had crossed the River Desna with 2nd Army on its right flank. The two Panzer armies now trapped four Soviet armies and parts of two others.

For its final attack on Leningrad, the 4th Panzer Army was reinforced by tanks from Army Group Centre. On 8 August the Panzers broke through the Soviet defenses; the German 16th Army attacked to the northeast, the 18th Army cleared Estonia and advanced to Lake Peipus. By the end of August, 4th Panzer Army had penetrated to within 30 miles (50 km) of Leningrad. The Finns had pushed southeast on both sides of Lake Ladoga reaching the old Finnish-Soviet frontier.

At this stage Hitler ordered the final destruction of Leningrad with no prisoners taken, and on 9 September Army Group North began the final push which within ten days brought it within 7 miles (10 km) of the city. However, the pace of advance over the last ten kilometers proved very slow and the casualties mounted. At this stage Hitler lost patience and ordered that Leningrad should not be stormed but starved into submission. He needed the tanks of Army Group North transferred to Army Group Centre for an all-out drive to Moscow.

Before the attack on Moscow could begin, operations in Kiev needed to be finished. Half of Army Group Centre had swung to the south in the back of the Kiev position, while Army Group South moved to the north from its Dniepr bridgehead. The encirclement of Soviet Forces in Kiev was achieved on 16 September. The encircled Soviets did not give up easily, and a savage battle ensued in which the Soviets were hammered with tanks, artillery, and aerial bombardment. In the end, after ten days of vicious fighting, the Germans claimed over 600,000 Soviet soldiers captured (but that was false, the German did capture 600,000 males between the ages of 15-70 but only 480,000 were soldiers, out of which 180,000 broke out, netting the Axis 300,000 Prisoners of war).[citation needed]

[edit] Final phase ( 2 October 1941 - 7 January 1942)

After Kiev, the Red Army no longer outnumbered the Germans and there were no more directly available trained reserves. To defend Moscow, Stalin could field 800,000 men in 83 divisions, but no more than 25 divisions were fully effective. Operation Typhoon, the drive to Moscow, began on October 2. In front of Army Group Centre was a series of elaborate defense lines, the first centered on Vyazma and the second on Mozhaisk.

The first blow took the Soviets completely by surprise as 2nd Panzer Army returning from the south took Orel which was 75 miles (121 km) south of the Soviet first main defence line. Three days later the Panzers pushed on Bryansk while 2nd Army attacked from the west. Three Soviet armies were now encircled. To the north, the 3rd and 4th Panzer Armies attacked Vyazma, trapping another five Soviet armies. Moscow's first line of defence had been shattered. The pocket yielded 663,000 Soviet prisoners, bringing the tally since the start of the invasion to three million Soviet soldiers captured. The Soviets had only 90,000 men and 150 tanks left for the defense of Moscow.

On 13 October 3rd Panzer Army penetrated to within 90 miles (140 km) of the capital. Martial law was declared in Moscow. Almost from the beginning of Operation Typhoon the weather had deteriorated. Temperatures fell while there was a continued rainfall, turning the unmetalled road network into mud and steadily slowing the German advance on Moscow to as little as 2 miles (3 km) a day. The supply situation rapidly deteriorated. On 31 October the Germany Army High Command ordered a halt to Operation Typhoon while the armies were re-organized. The pause gave the Soviets (who were in a far better supply situation due to the use of their rail network) time to reinforce, and in little over a month the Soviets organized eleven new armies which included 30 divisions of Siberian troops[citation needed]. These had been freed from the Soviet far east as Soviet intelligence had assured Stalin there was no longer a threat from the Japanese. With the Siberian forces would come over 1,000 tanks and 1,000 aircraft.[citation needed]

The Germans were nearing exhaustion, they also began to recall Napoleon's invasion of Russia. General Günther Blumentritt noted in his diary:

They remembered what happened to Napoleon's Army. Most of them began to re-read Caulaincourt's grim account of 1812. That had a weighty influence at this critical time in 1941. I can still see Von Kluge trudging through the mud from his sleeping quarters to his office and standing before the map with Caulaincourt's book in his hand.[72]

On 15 November with the ground hardening due to the cold weather, the Germans once again began the attack on Moscow. Although the troops themselves were now able to advance again, there had been no delay allowed to improve the supply situation. Facing the Germans were six Soviet armies. The Germans intended to let 3rd and 4th Panzer Armies cross the Moscow Canal and envelop Moscow from the northeast. 2nd Panzer Army would attack Tula and then close in on Moscow from the south. As the Soviets reacted to the flanks, 4th Army would attack the center. In two weeks of desperate fighting, lacking sufficient fuel and ammunition, the Germans slowly crept towards Moscow. However, in the south, 2nd Panzer Army was being blocked. On 22 November Soviet Siberian units attacked the 2nd Panzer Army and inflicted a defeat on the Germans. However, 4th Panzer Army succeeded in crossing the Moscow canal and began the encirclement.

On 2 December the 4th Panzer Army had penetrated to within 15 miles (24 km) of Moscow, but by then the first blizzards of the winter began. The Wehrmacht was not equipped for winter warfare. Frostbite and disease caused more casualties than combat, and dead and wounded had already reached 155,000 in three weeks. Some divisions were now at fifty percent strength. The bitter cold also caused severe problems for their guns and equipment, and weather conditions grounded the Luftwaffe. Newly built up Soviet units near Moscow now numbered over 500,000 men and on December 5 they launched a massive counterattack which pushed the Germans back over 320 kilometers (200 miles). The invasion of the USSR would cost the German Army over 250,000 dead and 500,000 wounded, the majority of whom became casualties after October 1 and an unknown number of Axis casualties such as Hungarians, Romanians and Waffen SS troops as well as co-belligerent Finns

[edit] Later events

It is sometimes argued that the fatal decision of the operation was the postponement from the original date of May 15 because Hitler wanted to intervene against an anti-German coup in Yugoslavia and Greek advances against Italy's occupation of Albania. However, this was just one of the reasons for the postponement — the other was the late spring of 1941 in Russia, compounded by particularly rainy weather during June 1941 which made a number of roads in western parts of the Soviet Union impassable to heavy vehicles. During the campaign, Hitler ordered the main thrust toward Moscow to be diverted southward in order to help the southern army group capture Ukraine. This move delayed the assault on the Soviet capital, although it also helped to secure Army Group Center's southern flank. By the time they turned their sights on Moscow, the fierce resistance of the Red Army, assisted by the mud following the autumn rains and eventually the winter snowfall, brought their advance to a halt.

In addition, resistance by the Soviets, who proclaimed a Great Patriotic War in defence of the motherland, was much fiercer than the German command had expected. The border fortress of Brest, Belarus illustrates that tenacity: attacked on the very first day of the German invasion, the fortress was expected to be captured by surprise within hours, but held out for weeks (Soviet propaganda later asserted that it held out for six weeks).[73] German logistics also became a major problem, as supply lines became very long and vulnerable to Soviet partisan attacks in the rear. The Soviets carried out a scorched earth policy on some of the land they were forced to abandon in order to deny the Germans the use of food, fuel, and buildings.

Despite the setbacks, the Germans continued to advance, often destroying or surrounding whole armies of Soviet troops and forcing them to surrender. The battle for Kiev was especially brutal. On 19 September Army Group South seized control of Kiev, and took 665,000 Soviets prisoner. Kiev was later awarded the title Hero City for its heroic defence.

Army Group North, which was to conquer the Baltic countries and eventually Leningrad, advanced as far as the southern outskirts of Leningrad by August 1941. There, fierce Soviet resistance stopped it. Since capturing the city seemed too costly, German command decided to starve the city to death by a blockade, starting the Siege of Leningrad. The city held out, despite several attempts by the Germans to break through its defenses, unrelenting air and artillery attacks, and severe shortages of food and fuel, until the Germans were driven back again from the city's approaches in early 1944. Leningrad was the first Soviet city to receive the title of 'Hero City'.

In addition to the main attacks of Barbarossa, German forces occupied Finnish Petsamo in order to secure important nickel mines. They also launched the beginning of a series of attacks against Murmansk on 28 June 1941. That assault was known as Operation Silberfuchs.

[edit] Causes of initial Soviet defeats

The Red Army and air force were so badly defeated in 1941 chiefly because they were ill-prepared for the surprise attack by the armed forces of the Axis, which by 1941 were the most experienced and best-trained in the world. The Axis had a doctrine of mobility and annihilation, excellent communications, and the confidence that comes from repeated low-cost victories. The Soviet armed forces, by contrast, lacked leadership, training, and readiness. Much of Soviet planning assumed that no war would take place before 1942: thus the Axis attack came at a time when new organizations and promising, but untested, weapons were just beginning to trickle into operational units. And much of the Soviet Army in Europe was concentrated along the new western border of the Soviet Union, in former Polish territory which lacked significant defences, allowing many Soviet military units to be overrun and destroyed in the first weeks of war. Initially, many Soviet units were also hampered by Semyon Timoshenko's and Georgy Zhukov's prewar orders (demanded by Joseph Stalin) not to engage or to respond to provocations (followed by a similarly damaging first reaction from Moscow, an order to stand and fight, then counterattack; this left those military units vulnerable to German encirclements), by a lack of experienced officers, and by bureaucratic inertia.

The initial tactical errors of the Soviets in the first few weeks of the Axis offensive proved catastrophic. Initially, the Red Army was fooled by a complete overestimation of its own capabilities. Instead of intercepting German armour, Soviet mechanised corps were ambushed and destroyed after Luftwaffe dive bombers inflicted heavy losses. Soviet tanks, poorly maintained and manned by inexperienced crews, suffered from an appalling rate of breakdowns. Lacks of spare parts and of trucks ensured a logistical collapse. The decision not to dig in the infantry divisions proved disastrous. Without tanks or sufficient motorisation, Soviet troops were incapable of waging mobile warfare against the Germans and their allies.

Stalin's orders to his troops not to retreat or surrender resulted in a return to static linear positions which German tanks easily breached, again quickly cutting supply lines and surrounding whole Soviet armies. Only later did Stalin allow his troops to retreat to the rear wherever possible and regroup, to mount a defence in depth or to counterattack. More than 2.4 million Soviet troops had been taken prisoner by December, 1941, by which time German and Soviet forces were fighting almost in the suburbs of Moscow. Most of these captured Soviet troops were to die from exposure, starvation, disease, or willful mistreatment by the German regime.

Despite the failure of the Axis to achieve Barbarossa's initial goals, the huge Soviet losses caused a shift in Soviet propaganda. Before the onset of hostilities against Germany, the Soviet government had stated that its army was very strong. But, by the autumn of 1941, the Soviet line was that the Red Army had been weak, that there had not been enough time to prepare for war, and that the German attack had come as a surprise.

Viktor Suvorov gives an alternative explanation in his Icebreaker. The larger and better equipped Soviet armed forces, according to Suvorov, were preparing their own surprise offensive against Axis forces, targeting especially their oil supplies in Romania: Suvorov's sources suggest that July 6, 1941 – two weeks later than the actual German invasion – had been set as the start of Soviet Operation "Thunderstorm".[74] Russian historian Boris Sokolov, exploring pre-war Soviet planning, also concluded that after the German invasion on June 22, 1941, the Red Army undertook counterattacks within the framework of the planned offensive and that the subsequent defensive operations of the Soviet Army, in view of the absence of pre-war defensive plans, were merely improvised:[75] hence the initial gigantic defeats.

In addition, Soviet imports of large amounts of raw materials to Germany provided by agreements during the countries' economic relationship proved vital to the initial success of the German invasion. Without Soviet imports, German stocks would have run out in several key products by October 1941, within three and a half months.[76] Germany would have been completely out of rubber and grain on the first day of the invasion were it not for Soviet imports:[76]

-

Tot USSR

importsJune 1941

German StocksJune 1941 (w/o

USSR imports)Oct 1941

German StocksOct 1941 (w/o

USSR imports)Oil Products 912 1350 438 905 -7 Rubber 18.8 13.8 -4.9 12.1 -6.7 Manganese 189.5 205 15.5 170 -19.5 Grain 1637.1 1381 -256.1 761 -876.1 *German stocks in thousands of tons (with and without USSR imports-Oct 1941 aggregate)

Without Soviet deliveries of these four major items, Germany could barely have attacked the Soviet Union, let alone come close to victory, even with more intense rationing.[77]

[edit] Outcome

The climax of Operation Barbarossa came when Army Group Centre, already short on supplies because of the October mud, was ordered to advance on Moscow; forward units came within sight of the spires of the Kremlin in early December 1941. Soviet troops, well supplied and reinforced by fresh divisions from Siberia, defended Moscow in the Battle of Moscow, and drove the Germans back as the winter advanced. The bulk of the counter-offensive was directed at Army Group Center, which was closest to Moscow.

With no shelter, few supplies, inadequate winter clothing, chronic food shortages, and nowhere to go, German troops had no choice but to wait out the winter in the frozen wasteland. The Germans managed to avoid being routed by Soviet counterattacks but suffered heavy casualties from battle and exposure.

At the time, the seizure of Moscow was considered the key to victory for Germany. Historians currently debate whether or not loss of the Soviet capital would have caused the collapse of the Soviet Union, but Operation Barbarossa failed to achieve that goal. In December 1941, Germany joined Japan in declaring war against the United States. Within six months from the start of Operation Barbarossa, the strategic position of Germany had become desperate, since German military industries were unprepared for a long war.

The outcome of Operation Barbarossa was at least as detrimental to the Soviets as it was to the Germans, however. Although the Germans had failed to take Moscow outright, they held huge areas of the western Soviet Union, including the entire regions of what are now Belarus, Ukraine, and the Baltic states, plus parts of Russia proper west of Moscow. German forces had advanced 1 689 kilometers (1,050 miles), and maintained a linearly-measured front of 3,058 kilometers (1,900 miles) .[78] The Germans held up to 500,000 square miles (1,300,000 km2) of territory with over 75 million people at the end of 1941, and would go on to seize another 250,000 square miles (650,000 km2) before being forced to retreat after defeats at Stalingrad and Kursk. However, the occupied areas were not always properly controlled by the Germans and underground activity rapidly escalated. Wehrmacht occupation had been brutal from the start, due to directives issued by Hitler himself at the start of the operation, according to which Slavic peoples were considered an inferior race of untermenschen. This attitude immediately alienated much of the population from the Nazis, while in some areas at least (for example, Ukraine) it seems that some local people had been ready to consider the Germans as liberators helping them to get rid of Stalin. Anti-German partisan operations intensified when Red Army units which had dissolved into the country's large uninhabited areas re-emerged as underground forces, which intensified under the repressive policies of the German armies. The Germans held on as stubbornly as possible in the face of Soviet counterattacks, resulting in huge casualties on both sides in many battles.

The war on the Eastern Front went on for four years. The death toll may never be established with any degree of certainty. The most recent western estimate of Soviet military deaths is 7 million that lost their lives either in combat or in Axis captivity. Soviet civilian deaths remain under contention, though roughly 20 million is a frequently cited figure. German military deaths are also not clarified to a large extent. The most recent German estimate (Rüdiger Overmans) concluded that about 4.3 million Germans and a further 900,000 Axis forces lost their lives either in combat or in Soviet captivity. Operation Barbarossa is listed among the most lethal battles in world history.

The Soviet Union had not signed the Geneva Convention (1929). However, a month after the German invasion in 1941, an offer was made for a reciprocal adherence to the Hague convention. This 'note' was left unanswered by Third Reich officials.[79]

[edit] Causes of the failure of Operation Barbarossa

The grave situation in which the beleaguered German army found itself, towards the end of 1941 was due to the increasing strength of the Red Army, compounded by a number of factors which in the short run severely restricted the effectiveness of the German forces. Chief among these were their overstretched deployment, a serious transport crisis affecting supply and movement and the eroded strength of most divisions. The infantry deficit that appeared by September 1, 1941 was never made good. For the rest of the war in the Soviet Union, the Wehrmacht would be short of infantry and support services.

Parallels have been drawn with Napoleon's invasion of Russia.

[edit] Underestimated Soviet potential

| This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2008) |

German war planners grossly underestimated the mobilization potential of the Red Army: its primary mobilisation size (i.e. the total of already trained units that could be put on a war-footing in short time) was about twice as large as they had expected. By early August, new armies had taken the place of the destroyed ones. This fact alone implied the failure of Operation Barbarossa, for the Germans now had to limit their operations for a month to bring up new supplies, leaving only six weeks to complete the battle before the start of the mud season, an impossible task. On the other hand, the Red Army proved capable of replacing its huge losses in a timely fashion, and was not destroyed as a coherent force. When the divisions consisting of conscripts trained before the war were destroyed, they were replaced by new ones, on average about half a million men being drafted each month for the duration of the war. The Soviets also proved very skilled in raising and training many new armies from the different ethnic populations of the far flung republics. It was this Soviet ability to mobilise vast (if often badly trained and equipped) forces within a short time and on a continual basis which allowed the Soviet Union to survive the critical first six months of the war, and the grave underestimation of this capacity which rendered German planning unrealistic.

In addition, data collected by Soviet intelligence excluded the possibility of a war with Japan, which allowed the Soviets to transfer forces from the Far East (troops who were fully trained to fight a winter war) to the European theatre.

The German High Command grossly underestimated the effective control the central Soviet government exercised. The German High Command incorrectly believed the Soviet government was ineffective. The Germans based their hopes of quick victory on the belief the Soviet communist system was like a rotten structure which would collapse from a hard kick.[80] In fact, the Soviet system proved resilient and surprisingly adaptable. In the face of early crushing defeats, the Soviets managed to dismantle entire industries threatened by the German advance. These critical factories, along with their skilled workers, were transported by rail to secure locations beyond the reach of the German army. Despite the loss of raw materials and the chaos of an invasion, the Soviets managed to build new armaments factories in sufficient numbers to allow the mass production of needed war machinery. The Soviet government was never in danger of collapse and remained at all times in tight control of the Soviet war effort.

The Germans treated Soviet prisoners with brutality and exhibited cruelty toward overrun Soviet populations. The effect of this treatment instilled a deep hatred in the hearts and minds of the Soviet citizens. Hatred of the Germans enabled the Soviet government to extract a level of sacrifice from the Soviet population unheard of in Western nations.

The Germans underestimated the Soviet people as well. The German High Command viewed Soviet soldiers as incompetent and considered the average citizen as an inferior human being. German soldiers were stunned by the ferocity with which the Red Army fought. German planners were amazed at the level of suffering the Soviet citizens could endure and still work and fight.

A further reason for the German defeat was the underestimation of Soviet technical and productive capacity.

[edit] Faults of logistical planning

At the start of the war in the dry summer, the Germans took the Soviets by surprise and destroyed a large part of the Soviet Red Army in the first weeks. When favorable weather conditions gave way to the harsh conditions of the autumn and winter and the Red Army recovered, the German offensive began to falter. The German army could not be sufficiently supplied for prolonged combat; indeed there was simply not enough fuel available to let the whole of the army reach its intended objectives.

This was well understood by the German supply units even before the operation, but their warnings were disregarded.[81] The entire German plan was based on the premise that within five weeks the German troops would have attained full strategic freedom due to a complete collapse of the Red Army. Only then would it have been possible to divert necessary logistic support to the fuel requirements of the few mobile units needed to occupy the defeated state.

German infantry and tanks stormed 300 miles (500 km) ahead in the first week, but their supply lines struggled to keep up. Soviet railroads could at first not be used due to a difference in railway gauges, until a sufficient supply of trains was seized.[citation needed] Lack of supplies significantly slowed down the blitzkrieg.

The German logistical planning also seriously overestimated the condition of the Soviet transportation network. The road and railway network of former Eastern Poland was well known, but beyond that information was limited. Roads that looked impressive on maps turned out to be just mere dust roads or were only in the planning stages.[81]

[edit] Weather

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2008) |

A paper published by the U.S. Army's Combat Studies Institute in 1981 concluded that Hitler's plans miscarried before the onset of severe winter weather. He was so confident of quick victory that he did not prepare for even the possibility of winter warfare in the Soviet Union. Nonetheless, his eastern army suffered more than 734,000 casualties (about 23 percent of its average strength of 3,200,000 troops) during the first five months of the invasion, and on 27 November 1941, General Eduard Wagner, the Quartermaster General of the German Army, reported that "We are at the end of our resources in both personnel and material. We are about to be confronted with the dangers of deep winter."[82]

The German forces were not prepared to deal with harsh weather and the poor road network of the USSR. In autumn, the terrain slowed the Wehrmacht’s progress. Few roads were paved. The ground in the USSR was very loose sand in the summer, sticky muck in the autumn, and heavy snow during the winter. The German tanks had narrow treads with little traction and poor flotation in mud. In contrast, the new generation of Soviet tanks such as the T-34 and KV had wider tracks and were far more mobile in these conditions. The 600,000 large western European horses the Germans used for supply and artillery movement did not cope well with this weather. The small ponies used by the Red Army were much better adapted to this climate and could even scrape the icy ground with their hooves to dig up the weeds beneath.

German troops were mostly unprepared for the harsh weather changes in the autumn and winter of 1941. Equipment had been prepared for such winter conditions, but the ability to move it up front over the severely overstrained transport network did not exist. Consequently, the troops were not equipped with adequate cold-weather gear, and some soldiers had to pack newspapers into their jackets to stay warm while temperatures dropped to record levels of at least -30 °C (-22 °F). To operate furnaces and heaters, the Germans also burned precious fuel that was difficult to re-supply. Soviet soldiers, in contrast, often had warm, quilted uniforms, felt-lined boots, and fur hats.

Some German weapons malfunctioned in the cold. Lubricating oils were unsuitable for extreme cold, resulting in engine malfunction and misfiring weapons. To load shells into a tank’s main gun, frozen grease had to be chipped off with a knife. Soviet units faced less severe problems due to their experience with cold weather. Aircraft were supplied with insulating blankets to keep their engines warm while parked. Lighter-weight oil was used. Tanks and armored vehicles were unable to move due to a lack of antifreeze, causing fuel to solidify and further slowing the German advance.

A common myth is that the combination of deep mud, followed by snow, stopped all military movement in the harsh Russian winter. In fact, military operations were slowed by these factors, but much more so on the German side than on the Soviet side. The Soviet December 1941 counteroffensive advanced up to 100 miles (160 km) in some sectors, demonstrating that mobile warfare was still possible under winter conditions.

When the severe winter began, Hitler became fearful of a repetition of Napoleon's disastrous retreat from Moscow, and quickly ordered the German forces to hold their ground defiantly wherever possible in the face of Soviet counterattacks. This became known as the "stand or die" order. This prevented the Germans from being routed, but resulted in heavy casualties from battle and cold.

[edit] Aftermath

Stalin deported German POWs to labour camps. Ethnic groups were also deported en masse to the east. Examples include: in September 1941, 439,000 Volga Germans (as well as more than 300,000 other Germans from various locations) were deported mainly to Kazakhstan as their autonomous republic was abolished by Stalin's decree; in May 1944, 182,000 Crimean Tatars were deported from the Crimea to Uzbekistan; and the complete deportation of Chechens (393,000) and Ingushs (91,000) to Kazakhstan took place in 1944 (see Population transfer in the Soviet Union).

Germany's inability to achieve victory over the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa opened up the possibility for Soviet counterattacks to retake lost land and attack further into Germany proper. Starting in mid-1944, the overwhelming success in Operation Bagration and the quick victory in the Lvov-Sandomierz Offensive led to an unbroken string of Soviet gains and unsupportable losses for the German forces. Operation Barbarossa's failure paved the way for Soviet forces to fight all the way to Berlin, cementing the ultimate fall of Nazism and Germany's defeat in World War II.

[edit] See also

- Eastern Front (World War II)

- Timeline of the Eastern Front of World War II

- Siege of Leningrad - the siege began in 1941 and was ended in 1944.

- Continuation War – the war at Finnish front

- Operation Silberfuchs – the attack on the Soviet Arctic

- Molotov Line – An incomplete Soviet defence line at the start of Operation Barbarossa

- Operation Nordlicht – Summer of 1942 was another major attack against besieged Leningrad

- Operation Blaufuchs – German–Finnish general operational plans

- Captured Tanks and Armoured cars for German use in Russian Front

- Captured German equipment in Soviet use on the Eastern front

- Pobediteli – Russian project celebrating the 60th anniversary of World War II

- The Battle of Russia – film from the Why We Fight propaganda film series

[edit] Notes

- ^ Bergström, p130

- ^ Bergström 2007, p. 131-2: Uses Soviet Record Archives including the Rosvoyentsentr, Moscow; Russian Aviation Research Trust; Russian Central Military Archive TsAMO, Podolsk; Monino Air Force Museum, Moscow.

- ^ Bergström 2007, p 118: Sources Luftwaffe strength returns from the Archives in Freiburg.

- ^ Krivosheev, G.F, 1997, p.96. Documented losses only

- ^ About the German Invasion of the Soviet Union

- ^ THE TREATMENT OF SOVIET POWS: STARVATION, DISEASE, AND SHOOTINGS, JUNE 1941- JANUARY 1942

- ^ Bergström, p117

- ^ Krivosheyev, G. 1993

- ^ Note: Soviet aircraft losses include all causes

- ^ a b Higgins, Trumbull (1966). Hitler and Russia. The Macmillan Company. pp. 11–59, 98–151.

- ^ Bryan I. Fugate. Strategy and tactics on the Eastern Front, 1941. Novato: Presidio Press, 1984.

- ^ World War II Chronicle, 2007. Legacy/ Publications International, Ltd. Page 146.

- ^ A.J.P Taylor & Colonel D. M Proektor, p106

- ^ A.J.P Taylor & Colonel D. M Proektor 1974, p. 107

- ^ Simonov, Konstantin (1979). "Records of talks with Georgi Zhukov, 1965–1966". Hrono. http://www.hrono.ru/dokum/197_dok/1979zhukov2.html.