Dust Bowl

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2008) |

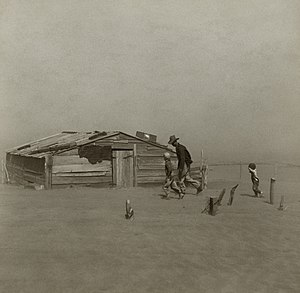

The Dust Bowl or the Dirty Thirties was a period of severe dust storms causing major ecological and agricultural damage to American and Canadian prairie lands from 1930 to 1936 (in some areas until 1940). The phenomenon was caused by severe drought coupled with decades of extensive farming without crop rotation or other techniques to prevent erosion. Deep plowing of the virgin topsoil of the Great Plains had killed the natural grasses that normally kept the soil in place and trapped moisture even during periods of drought and high winds.

During the drought of the 1930s, with no natural anchors to keep the soil in place, it dried, turned to dust, and blew away eastward and southward in large dark clouds. At times the clouds blackened the sky reaching all the way to East Coast cities such as New York and Washington, D.C. Much of the soil ended up deposited in the Atlantic Ocean. These immense dust storms–given names such as "Black Blizzards" and "Black Rollers"–often reduced visibility to a few feet (around a meter). The Dust Bowl affected 100,000,000 acres (400,000 km2), centered on the panhandles of Texas and Oklahoma, and adjacent parts of New Mexico, Colorado, and Kansas.[1] The Dust Bowl was an ecological and human disaster caused by misuse of land and years of sustained drought. Millions of acres of farmland became useless, and hundreds of thousands of people were forced to leave their homes; many of these families (often known as "Okies", since so many came from Oklahoma) traveled to California and other states, where they found economic conditions little better than those they had left. Owning no land, many traveled from farm to farm picking fruit and other crops at starvation wages. Author John Steinbeck later wrote Of Mice and Men and The Grapes of Wrath about such people. The latter won both Pulitzer and Nobel prizes.

Contents |

Causes

Agricultural and settlement history

During early European and American exploration of the Great Plains, the region in which the Dust Bowl occurred was thought unsuitable for European-style agriculture; indeed, the region was known as the Great American Desert. The lack of surface water and timber made the region less attractive than other areas for pioneer settlement and agriculture. However, following the Civil War, settlement in the area increased, encouraged by the Homestead Act and westward expansion.[2][3] An unusually wet period in the Great Plains mistakenly led settlers and government to believe that "rain follows the plow" and that the climate of the region had changed permanently.[4] The initial agricultural endeavors were primarily cattle ranching with some cultivation; however, a series of harsh winters beginning in 1886, coupled with overgrazing followed by a short drought in 1890, led to an expansion of land under cultivation.

Immigration began again at the beginning of the 20th century. A return of unusually wet weather confirmed the previously held opinion that the "formerly" semi-arid area could support large-scale agriculture. Technological improvements led to increased automation, which allowed for cultivation on an ever greater scale. World War I increased agricultural prices, which also encouraged farmers to drastically increase cultivation. In the Llano Estacado, farmland area doubled between 1900 and 1920, and land under cultivation more than tripled between 1925 and 1930.[5] Finally, farmers used agricultural practices that encouraged erosion.[citation needed] For example, cotton farmers left fields bare over winter months, when winds in the High Plains are highest, and burned the stubble, which deprived the soil of organic nutrients and increased exposure to erosion.

This increased exposure to erosion was revealed when a severe drought struck the Great Plains in 1934. The native grasses that covered the prairie lands for centuries, holding the soil in place and maintaining its moisture had been eliminated by the intensively increased plowing. The drought conditions caused the topsoil to grow dry and friable and it was simply carried away by the wind. The dusty soil aggregated in the air forming immense dust clouds which further prevented rainfall. It was not until the government promoted soil conservation programs that the area slowly began to rehabilitate. [6]

Geographic characteristics

The Dust Bowl area lies principally west of the 100th meridian on the High Plains, characterized by plains which vary from rolling in the north to flat in the Llano Estacado. Elevation ranges from 2,500 feet (760 m) in the east to 6,000 feet (1,800 m) at the base of the Rocky Mountains. The area is semi-arid, receiving less than 20 inches (510 mm) of rain annually; this rainfall supports the Shortgrass prairie biome originally present in the area. The region is also prone to extended drought, alternating with unusual wetness of equivalent duration.[7] During wet years, the rich soil provides bountiful agricultural output, but crops fail during dry years. Furthermore, the region is subject to winds higher than any region except coastal regions.[8]

Drought and dust storms

The unusually wet period, which encouraged increased settlement and cultivation in the Great Plains, ended in 1930. This was the year in which an extended and severe drought began which caused crops to fail, leaving the plowed fields exposed to wind erosion. The fine soil of the Great Plains was easily eroded and carried east by strong continental winds.

On November 11, 1933, a very strong dust storm stripped topsoil from desiccated South Dakota farmlands in just one of a series of bad dust storms that year. Then, beginning on May 9, 1934, a strong two-day dust storm removed massive amounts of Great Plains topsoil in one of the worst such storms of the Dust Bowl. The dust clouds blew all the way to Chicago where dirt fell like snow. Two days later, the same storm reached cities in the east, such as Buffalo, Boston, New York City, and Washington, D.C.[9] That winter, red snow fell on New England.

On April 14, 1935, known as "Black Sunday", twenty of the worst "Black Blizzards" occurred throughout the Dust Bowl, causing extensive damage and turning the day to night; witnesses reported that they could not see five feet in front of them at certain points. The dust storms were so bad that often roosters thought that it was night instead of day and went to sleep during them.[citation needed]

Human displacement

This catastrophe intensified the economic impact of the Great Depression in the region. It fomented an exodus of the displaced from Texas, Oklahoma, and the surrounding Great Plains to adjacent regions. More than 500,000 Americans were left homeless. 356 houses had to be torn down after one storm alone.[10] Many Americans migrated west looking for work, while many Canadians fled to urban areas such as Toronto. Two-thirds of farmers in "Palliser's Triangle", in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, had to rely on government aid. This was due mainly to drought, hail storms, and erratic weather rather than to dust storms as was occurring on the U.S. Great Plains.[11] Some residents of the Plains, especially in Kansas and Oklahoma fell ill and died of either dust pneumonia or malnutrition.[citation needed]

The Dust Bowl exodus was the largest migration in American history within a short period of time. By 1940, 2.5 million people had moved out of the Plains states; of those, 200,000 moved to California.[12] With their land barren and homes seized in foreclosure, many farm families were forced to leave. Migrants left farms in Oklahoma, Kansas, Texas, Iowa, and New Mexico, but all were generally referred to as "Okies". The second wave of the Great Migration by African Americans from the South to the North was larger, involving more than 5 million people, but it took place over decades, from 1940-1970.[13]

Characteristics of migrants

When James N. Gregory examined the Census Bureau statistics as well as other surveys, he discovered some surprising percentages. For example, in 1939 the Bureau of Agricultural Economics surveyed the occupations of about 116,000 families who had arrived in California in the 1930s. It showed that only 43 percent of southwesterners were doing farmwork immediately before they migrated. Nearly one-third of all migrants were professional or white collar workers.[citation needed]

Government response

| This section requires expansion. |

During President Franklin D. Roosevelt's first 100 days in 1933, governmental programs designed to conserve soil and restore the ecological balance of the nation were implemented. Interior Secretary Harold L. Ickes established the Soil Erosion Service in August 1933 under Hugh Hammond Bennett. In 1935 it was reorganized and renamed the Soil Conservation Service. More recently it has been renamed the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS).[14]

Additionally, the Federal Surplus Relief Corporation (FSRC) was created after more than six million pigs were slaughtered to stabilize prices. The pigs went to waste. The FSRC diverted agricultural commodities to relief organizations. Apples, beans, canned beef, flour and pork products were distributed through local relief channels. Cotton goods were later included, to clothe the needy. [15]

In 1935, the federal government formed a Drought Relief Service (DRS) to coordinate relief activities. The DRS bought cattle in counties which were designated emergency areas, for $14 to $20 a head. Animals unfit for human consumption - more than 50 percent at the beginning of the program - were destroyed. The remaining cattle were given to the Federal Surplus Relief Corporation (FSRC) to be used in food distribution to families nationwide. Although it was difficult for farmers to give up their herds, the cattle slaughter program helped many of them avoid bankruptcy. "The government cattle buying program was a God-send to many farmers, as they could not afford to keep their cattle, and the government paid a better price than they could obtain in local markets."[16]

President Roosevelt ordered that Civilian Conservation Corps to plant a huge belt of more than 200 million trees from Canada to Abilene, Texas to break the wind, hold water in the soil, and hold the soil itself in place. The administration also began to educate farmers on soil conservation and anti-erosion techniques, including crop rotation, strip farming, contour plowing, terracing and other improved farming practices.[17] [18] In 1937, the federal government began an aggressive campaign to encourage Dust Bowlers to adopt planting and plowing methods that conserved the soil. The government paid the reluctant farmers a dollar an acre to practice one of the new methods. By 1938, the massive conservation effort had reduced the amount of blowing soil by 65 percent. Nevertheless, the land failed to yield a decent living. In the fall of 1939, after nearly a decade of dirt and dust, rain finally came.

Influence on the arts

| This section requires expansion. |

The human crisis was documented by photographers, musicians, and authors, many hired by various federal agencies. The Farm Security Administration hired numerous photographers, giving Dorothea Lange her start, in which she made a name for herself while capturing the impact of the storms and families of migrants. Independent artists such as folk singer Woody Guthrie and novelist John Steinbeck made art that grew out of the events of the Dust Bowl of the 1930s.

Migrants leaving the Plains states took their music with them. Oklahoma migrants, in particular, descended from rural Southerners earlier in the century, contributed greatly to the transplanting of country music to California. Today, the "Bakersfield Sound" describes this particular blend of country music which the migrants brought to the city. Their new music caused a proliferation of country dance halls as far South as Los Angeles.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Dust Bowl |

- 1936 North American heat wave

- Rain follows the plow

- The Plow That Broke the Plains

- Timeline of environmental events

- Natural disaster

- Desertification

- Ogallala Aquifer

- Palliser's Triangle

References

- ^ Hakim, Joy (1995). A History of Us: War, Peace and all that Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509514-6.

- ^ "The Great Plains: from dust to dust" (HTML). Planning Magazine. December 1987. http://www.planning.org/25anniversary/planning/1987dec.htm. Retrieved on December 6 2007.

- ^ (HTML)Regions at Risk: a comparison of threatened environments. United Nations University Press. 1995. http://www.unu.edu/unupress/unupbooks/uu14re/uu14re00.htm.

- ^ (HTML)Drought in the Dust Bowl Years. National Drought Mitigation Center. 2006. http://www.drought.unl.edu/whatis/dustbowl.htm.

- ^ (HTML)Regions at Risk: a comparison of threatened environments. United Nations University Press. 1995. http://www.unu.edu/unupress/unupbooks/uu14re/uu14re0n.htm#6.%20the%20ilano%20estacado%20of%20the%20american%20southern%20high%20plains.

- ^ "The American Experience : Surviving The Dust Bowl : People & Events : The Drought" (HTML). PBS. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/dustbowl/peopleevents/pandeAMEX06.html. Retrieved on 2008-12-29.

- ^ "A History of Drought in Colorado: lessons learned and what lies ahead" (PDF). Colorado Water Resources Research Institute. February 2000. http://ccc.atmos.colostate.edu/pdfs/ahistoryofdrought.pdf. Retrieved on 2007.

- ^ "A Report of the Great Plains Area Drought Committee" (HTML). Hopkins Papers, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library. August 27, 1936. http://newdeal.feri.org/hopkins/hop27.htm. Retrieved on December 6 2007.

- ^ Stock, Catherine McNicol (1992). Main Street in Crisis: The Great Depression and the Old Middle Class on the Northern Plains, p. 24. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807846899.

- ^ "First Measured Century: Interview:James Gregory". PBS. http://www.pbs.org/fmc/interviews/gregory.htm. Retrieved on 2007-03-11.

- ^ ""The Dust Bowl"". CBC. http://history.cbc.ca/history/?MIval=EpisContent.html&lang=E&series_id_1&episode_id=13&chapter_id=1&page_id=2. Retrieved on 2007-03-11.

- ^ Worster, Donald (1979). Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930's. Oxford University Press.

- ^ "In Motion: African American Migration Experience, The Second Great Migration". http://www.inmotionaame.org/migrations/topic.cfm?migration=9&topic=1. Retrieved on 2007-03-18.

- ^ Steiner, Frederick (2008). The Living Landscape, Second Edition: An Ecological Approach to Landscape Planning, p. 188. Island Press. ISBN 1597263966.

- ^ "The American Experience / Surviving the Dust Bowl / Timeline". http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/dustbowl/timeline/.

- ^ Monthly Catalog, United States Public Documents, By United States Superintendent of Documents, United States Government Printing Office, Published by G.P.O., 1938

- ^ Federal Writers' Project. Texas. Writers' Program (Tex.): Writers' Program Texas. p. 16.

- ^ Buchanan, James Shannon. Chronicles of Oklahoma. Oklahoma Historical Society. p. 224.

Bibliography

- Woody Guthrie, The (Nearly) Complete Collection of Woody Guthrie Folk Songs, Ludlow Music, New York (1963).

- Alan Lomax, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Hard-Hitting Songs for Hard-Hit People, Oak Publications, New York (1967).

- C. Vann Woodward, The Origins of the New South, Louisiana State University Press (1967).

- The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived The Great American Dust Bowl, Timothy Egan, Houghton Mifflin Company, New York, 2006, hardcover. ISBN 0-618-34697-X.

- The Dust Bowl: Men, Dirt, and Depression, Paul Bonnifield, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1978, hardcover. ISBN 0-8263-0485-0.

- Survival in the Storm: The Dust Bowl Diary of Grace Edwards, Dalhart, Texas, 1935, Katelan Janke, Scholastic (September 2002). ISBN 0-439-21599-4.

- Out of the Dust, Karen Hesse, Scholastic Signature. New York First Edition, 1997, hardcover (paperback January 1999). ISBN 0-590-37125-8.

External links

- NASA Explains "Dust Bowl" Drought

- The Dust Bowl photo collection

- The Dust Bowl (EH.Net Encyclopedia)

- Black Sunday, April 14, 1935, Dodge City, KS

- The Bibliography of Aeolian Research

- Surviving the Dust Bowl, Black Sunday (April 14, 1935)

- The Plow That Broke The Plains

- Youtube Video: "The Great Depression, Displaced Mountaineers in Shenandoah National Park, and the Civilian Conservation Corps (C.C.C.)"

- Farming in the 1930s (Wessels Living History Farm)

- The Dust Bowl (University of South Dakota)

- Black Blizzard (The History Channel)

- Flash: Out of the Dust (The Modesto Bee)

|

|||||||||||