Critical mass

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2008) |

A critical mass is the smallest amount of fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (e.g. the nuclear fission cross-section), its density, its shape, its enrichment, its purity, its temperature, and its surroundings.

Contents |

[edit] Explanation of criticality

The term critical refers to an equilibrium fission reaction (steady-state or continuous chain reaction); this is where there is no increase or decrease in power, temperature, or neutron population.

A numerical measure of a critical mass is dependent on the neutron multiplication factor, k, where:

- k = f − l

where f is the average number of neutrons released per fission event and l is the average number of neutrons lost by either leaving the system or being captured in a non-fission event. When k = 1 the mass is critical.

A subcritical mass is a mass of fissile material that does not have the ability to sustain a fission reaction. A population of neutrons introduced to a subcritical assembly will exponentially decrease, typically rapidly. In this case, k < 1. A steady rate of spontaneous fissions causes a proportional steady level of neutron activity. The constant of proportionality increases as k increases.

A supercritical mass is one where there is an increasing rate of fission. The material may settle into equilibrium (i. e. become critical again) at an elevated temperature/power level or destroy itself (disassembly is an equilibrium state). In the case of supercriticality, k > 1.

[edit] Changing the point of criticality

The point, and therefore the mass, where criticality occurs may be changed by modifying certain attributes, such as fuel, shape, temperature, density, and the installation of a neutron-reflective substance. These attributes have complex interactions and interdependencies, this section explains only the simplest ideal cases.

- Varying the amount of fuel

It is possible for a fuel assembly to be critical at near zero power. If the perfect quantity of fuel were added to a slightly subcritical mass to create an "exactly critical mass", fission would be self-sustaining for one neutron generation (fuel consumption makes the assembly subcritical).

If the perfect quantity of fuel were added to a slightly subcritical mass, to create a barely supercritical mass, the temperature of the assembly would increase to an initial maximum (for example: 1 K above the ambient temperature) and then decrease back to room temperature after a period of time, because fuel consumed during fission brings the assembly back to subcriticality once again.

- Changing the shape

A mass may be exactly critical, but not a perfect homogeneous sphere. Changing the shape to be closer to a perfect sphere will make the mass supercritical. Conversely, changing the shape to be further from a sphere will decrease its reactivity, making it subcritical.

- Changing the temperature

A mass may be exactly critical at a particular temperature. Increasing the temperature of the material, (assuming an ideal material that does not expand or contract, see Varying the density of the mass) will cause the atoms to vibrate faster which causes atoms to "see" and generate neutrons with a wider spread of velocities. This is termed doppler broadening and has a significant effect on generally reducing criticality (and hence increasing the required critical mass). This is because any U238 in the mass will now see and absorb more fast neutrons, thus removing them from the chain. (This is for a simple largely unreacted enriched Uranium 235 case, in practice detailed examinations of all isotopes and lifetimes are needed to determine the actual temperature coefficient, which can also be positive.)

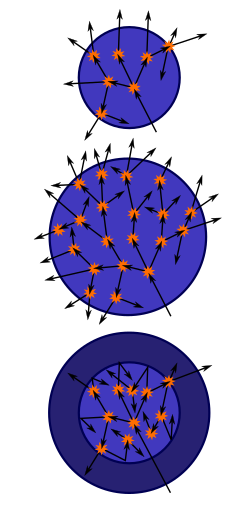

- Varying the density of the mass

The higher the density, the lower the critical mass. The density of a material at a constant temperature can be changed by varying the pressure or tension or by changing crystal structure (see Allotropes of plutonium). An ideal mass will become subcritical if allowed to expand or conversely the same mass will become supercritical if compressed. Changing the temperature may also change the density, however the effect on critical mass is then complicated by the temperature effects (See Changing the temperature), and by whether the material expands or contracts with increased temperature. Assuming the material expands with temperature (enriched Uranium 235 at room temperature for example), at an exactly critical state, it will become subcritical if warmed, hence lower density, or conversely the same mass will become supercritical if cooled, hence higher density. Such a material is said to have a negative temperature coefficient of reactivity to indicate that its reactivity decreases when its temperature increases. Using such a material as fuel means fission reduces as the fuel temperature increases.

- Use of a neutron reflector

Surrounding a spherical critical mass with a neutron reflector further reduces the mass needed for criticality. A good neutron reflector is beryllium metal. This increases the rate of neutron collisions, resulting in supercriticality.

[edit] Critical mass of a bare sphere

The shape with minimal critical mass and the smallest physical dimensions is a sphere. Bare-sphere critical masses at normal density of some actinides are listed in the following table.

| Nuclide | Critical Mass (kg) |

Diameter (cm) |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| protactinium-231 | 750±180 | 45±3 | |

| uranium-233 | 15 | 11 | [1] |

| uranium-235 | 52 | 17 | [1] |

| neptunium-236 | 7 | 8.7 | [2] |

| neptunium-237 | 60 | 18 | [3][4] |

| plutonium-238 | 9.04–10.07 | 9.5-9.9 | [5] |

| plutonium-239 | 10 | 9.9 | [1][5] |

| plutonium-240 | 40 | 15 | [1] |

| plutonium-241 | 12 | 10.5 | [6] |

| plutonium-242 | 75–100 | 19-21 | [6] |

| americium-241 | 55–77 | 20-23 | [7] |

| americium-242m | 9–14 | 11-13 | [7] |

| americium-243 | 180–280 | 30-35 | [7] |

| curium-243 | 7.34–10 | 10-11 | [8] |

| curium-244 | (13.5)–30 | (12.4)–16 | [8] |

| curium-245 | 9.41–12.3 | 11-12 | [8] |

| curium-246 | 39–70.1 | 18-21 | [8] |

| curium-247 | 6.94–7.06 | 9.9 | [8] |

| californium-249 | 6 | 9 | [2] |

| californium-251 | 5 | 8.5 | [2] |

The critical mass for lower-grade uranium depends strongly on the grade: with 20% U-235 it is over 400 kg; with 15% U-235, it is well over 600 kg.

The critical mass is inversely proportional to the square of the density: if the density is 1% more and the mass 2% less, then the volume is 3% less and the diameter 1% less. The probability for a neutron per cm travelled to hit a nucleus is proportional to the density, so 1% more, which compensates that the distance travelled before leaving the system is 1% less. This is something that must be taken into consideration when attempting more precise estimates of critical masses of plutonium isotopes than the rough values given above, because plutonium metal has a large number of different crystal phases which can have widely varying densities.

Note that not all neutrons contribute to the chain reaction. Some escape. Others undergo radiative capture.

Let q denote the probability that a given neutron induces fission in a nucleus. Let us consider only prompt neutrons, and let ν denote the number of prompt neutrons generated in a nuclear fission. For example,  for uranium-235. Then, criticality occurs when νq = 1. The dependence of this upon geometry, mass, and density appears through the factor q.

for uranium-235. Then, criticality occurs when νq = 1. The dependence of this upon geometry, mass, and density appears through the factor q.

Given a total interaction cross section σ (typically measured in barns), the mean free path of a prompt neutron is  where n is the nuclear number density. Most interactions are scattering events, so that a given neutron obeys a random walk until it either escapes from the medium or causes a fission reaction. So long as other loss mechanisms are not significant, then, the radius of a spherical critical mass is rather roughly given by the product of the mean free path

where n is the nuclear number density. Most interactions are scattering events, so that a given neutron obeys a random walk until it either escapes from the medium or causes a fission reaction. So long as other loss mechanisms are not significant, then, the radius of a spherical critical mass is rather roughly given by the product of the mean free path  and the square root of one plus the number of scattering events per fission event (call this s), since the net distance travelled in a random walk is proportional to the square root of the number of steps:

and the square root of one plus the number of scattering events per fission event (call this s), since the net distance travelled in a random walk is proportional to the square root of the number of steps:

Note again, however, that this is only a rough estimate.

In terms of the total mass M, the nuclear mass m, the density ρ, and a fudge factor f which takes into account geometrical and other effects, criticality corresponds to

which clearly recovers the aforementioned result that critical mass depends inversely on the square of the density.

Alternatively, one may restate this more succinctly in terms of the areal density of mass, Σ:

where the factor f has been rewritten as f' to account for the fact that the two values may differ depending upon geometrical effects and how one defines Σ. For example, for a bare solid sphere of Pu-239 criticality is at 320 kg/m², regardless of density, and for U-235 at 550 kg/m². In any case, criticality then depends upon a typical neutron "seeing" an amount of nuclei around it such that the areal density of nuclei exceeds a certain threshold.

This is applied in implosion-type nuclear weapons, where a spherical mass of fissile material that is substantially less than a critical mass, is made supercritical by very rapidly increasing ρ (and thus Σ as well), see below. Indeed, sophisticated nuclear weapons programs can make a functional device from less material than more primitive weapons programs require.

Aside from the math, there is a simple physical analog that helps explain this result. Consider diesel fumes belched from an exhaust pipe. Initially the fumes appear black, then gradually you are able to see through them without any trouble. This is not because the total scattering cross section of all the soot particles has changed, but because the soot has dispersed. If we consider a transparent cube of length L on a side, filled with soot, then the optical depth of this medium is inversely proportional to the square of L, and therefore proportional to the areal density of soot particles: we can make it easier to see through the imaginary cube just by making the cube larger.

Several uncertainties contribute to the determination of a precise value for critical masses, including (1) detailed knowledge of cross sections, (2) calculation of geometric effects. This latter problem provided significant motivation for the development of the Monte Carlo method in computational physics by Nicholas Metropolis and Stanislaw Ulam. In fact, even for a homogeneous solid sphere, the exact calculation is by no means trivial. Finally note that the calculation can also be performed by assuming a continuum approximation for the neutron transport, so that the problem reduces to a diffusion problem. However, as the typical linear dimensions are not significantly larger than the mean free path, such an approximation is only marginally applicable.

Finally, note that for some idealized geometries, the critical mass might formally be infinite, and other parameters are used to describe criticality. For example, consider an infinite sheet of fissionable material. For any finite thickness, this corresponds to an infinite mass. However, criticality is only achieved once the thickness of this slab exceeds a critical value.

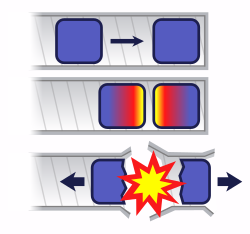

[edit] Criticality in nuclear weapon design

Until detonation is desired, a nuclear weapon must be kept subcritical. In the case of a uranium bomb, this can be achieved by keeping the fuel in a number of separate pieces, each below the critical size either because they are too small or unfavourably shaped. To produce detonation, the uranium is brought together rapidly. In Little Boy, this was achieved by firing a piece of uranium (a 'Doughnut'), down a gun barrel onto another piece, (a 'Spike'), a design referred to as a gun-type fission weapon.

A theoretical 100% pure Pu-239 weapon could also be constructed as a gun-type weapon. In reality, this is impractical because even "weapons grade" Pu-239 is contaminated with a small amount of Pu-240, which has a strong propensity toward spontaneous fission. Because of this, a reasonably sized gun-type weapon would suffer nuclear reaction before the masses of plutonium would be in a position for a full-fledged explosion to occur.

Instead, the plutonium is present as a subcritical sphere (or other shape), which may or may not be hollow. Detonation is produced by exploding a shaped charge surrounding the sphere, increasing the density (and collapsing the cavity, if present) to produce a prompt critical configuration. This is known as an implosion type weapon.

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ a b c d Nuclear Weapons Design & Materials, The Nuclear Threat Initiative website.

- ^ a b c Final Report, Evaluation of nuclear criticality safety data and limits for actinides in transport, Republic of France, INSTITUT DE RADIOPROTECTION ET DE SÛRETÉ NUCLÉAIRE, DÉPARTEMENT DE PRÉVENTION ET D'ÉTUDE DES ACCIDENTS.

- ^ Chapter 5, Troubles tomorrow? Separated Neptunium 237 and Americium, Challenges of Fissile Material Control (1999), isis-online.org

- ^ http://www.lanl.gov/news/index.php?fuseaction=home.story&story_id=1348[broken citation]

- ^ a b Updated Critical Mass Estimates for Plutonium-238, U.S. Department of Energy: Office of Scientific & Technical Information

- ^ a b Amory B. Lovins, Nuclear weapons and power-reactor plutonium, Reprinted from Nature, Vol. 283, No. 5750, pp. 817-823, February 28 1980) ©Macmillan Journals Ltd., 1980 by Rocky Mountain institute.[copyvio source?]

- ^ a b c http://typhoon.tokai-sc.jaea.go.jp/icnc2003/Proceeding/paper/6.5_022.pdf[broken citation] Dias et. al.

- ^ a b c d e Hirshi Okuno and Hirumitsu Kawasaki, Technical Report, Critical and Subcritical Mass Calculations for Curium-243 to -247 , Japan National Institute of Informatics, Reprinted from Joournal of Nuclear Science and technology, Vol.39 No.10 p.1072-1085 (October 2002)[copyvio source?]