Jaco Pastorius

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Jaco Pastorius | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Background information | |

| Birth name | John Francis Pastorius III |

| Born | December 1, 1951 |

| Origin | Norristown, Pennsylvania |

| Died | September 21, 1987 (aged 35) Fort Lauderdale, Florida, USA |

| Genre(s) | Jazz, Jazz fusion, Funk, Jazz-funk |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, songwriter |

| Instrument(s) | Bass guitar, Drums, Piano, Saxophone |

| Years active | 1964–1987 |

| Label(s) | Epic, Warner Bros., Columbia |

| Associated acts | Weather Report, Othello Molineaux |

| Website | JacoPastorius.com |

| Notable instrument(s) | |

| Fretless Fender Jazz Bass | |

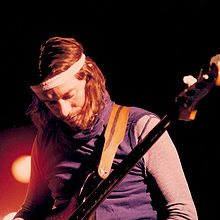

John Francis Anthony "Jaco" Pastorius III (December 1, 1951–September 21, 1987) was an American jazz musician and composer widely acknowledged for his skills as an electric bass player,[1][2] as well as his command of varied musical styles including jazz, jazz fusion, funk, and jazz-funk. He is regarded as one of the most influential bass players of all time.

His playing style was noteworthy for containing intricate solos in the higher register. His innovations also included the use of harmonics[3] and the "singing" quality of his melodies on fretless bass. In 2006, Pastorius was voted "The Greatest Bass Player Who Has Ever Lived" by reader submissions in Bass Guitar magazine.[2] He was inducted into Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame in 1988, one of only four bassists to be so honored (the others being Charles Mingus, Milt Hinton, and Ray Brown), and the only electric bassist to receive this distinction. In his 30s,[1] Pastorius suffered from mental illness and substance abuse, and was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 1985.[3] He died in 1987 from a physical beating sustained from a doorman while trying to gain entry into the Midnight Club in Fort Lauderdale at age 35.[1]

Contents |

[edit] Early life and education

John Francis Pastorius III was born December 1, 1951 in Norristown, Pennsylvania[2] to Jack Pastorius (big band singer/drummer) and Stephanie Katherine Haapala Pastorius,[4] the first of their three children. Pastorius was of Finnish, German, Swedish and Irish ancestry.[4]

Shortly after his birth, his family moved to Oakland Park, Florida (near Fort Lauderdale). Pastorius went to elementary and middle school at St. Clement's Catholic School in Wilton Manors, and he was an altar boy at the adjoining church.[5] In his years at St. Clement's, the art he was most known for was drawing.

Pastorius formed his first band named The Sonics along with John Caputo and Dean Noel. He went to high school at Northeast High in Oakland Park.[6] He was a talented athlete with skills in football, basketball, and baseball, and he picked up music at an early age. He took the name "Anthony" at his confirmation.[7]

He loved basketball and often watched it with his father. Pastorius' nickname was influenced by his love of sports and also by the umpire Jocko Conlan.[7] He changed the spelling from "Jocko" to "Jaco" after the pianist Alex Darqui sent him a note. Darqui, who was French, assumed the name was spelled "Jaco"; Pastorius liked the new spelling.[7] Jaco had a second nickname, given to him by his younger brother Gregory: "Mowgli", after the wild young boy in Rudyard Kipling's classic The Jungle Book. Gregory gave him the nickname in reference to Jaco's seemingly endless energy as a child.[7] Jaco would later establish his music publishing company as Mowgli Music. In 1973, he was an instructor at the University of Miami's famed school of music.

[edit] Music career

Pastorius started his musical career as a drummer[2] (following in the footsteps of his father Jack, a stand-up drummer) but when he was 13, he injured his wrist while playing football.[3] The break was so severe it caused calcium to build up in his wrist and required corrective surgery. After that he was never able to hit a snare drum properly again.[6] At that time he was in a nine-piece horn band called Las Olas Brass (which covered popular material of the day by Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, James Brown and the Tijuana Brass.) Rendered unable to play the drums, he decided to fill in the spot left open by the recently departed bass player.[2]

As Pastorius' interest in jazz grew, he developed a desire to play the double bass. After saving money for a considerable length of time for the purchase of a double bass, he found that the instrument could not stand up to the Florida humidity. One morning, his double bass was "in like a hundred pieces" as he put it..[8] Deciding that to replace it would be too expensive, he instead pried out the frets on his Fender, filled the fret holes with wood putty, and coated the fingerboard with marine varnish[8]

He continued to play music throughout his youth, drawing on aforementioned influences like Jerry Jemmott, James Jamerson, Paul Chambers, Harvey Brooks, and Tommy Cogbill and honing his skills and developing his songwriting prowess in bands like Wayne Cochran and The C.C. Riders.[2] He also played on various local R&B and jazz records during that time such as Little Beaver, Ira Sullivan's Quintet, and Woodchuck. In 1974, he began playing with his friend and later famous jazz guitarist Pat Metheny. They recorded together, first with Paul Bley as leader and Bruce Ditmas on drums, then with drummer Bob Moses. Metheny and Jaco recorded a trio album with Bob Moses on the ECM label, entitled Bright Size Life.

[edit] Debut album

In 1975, Pastorius met up with Blood, Sweat and Tears drummer Bobby Colomby, who had been given the green light by CBS records to find "new talent" for their jazz division.[citation needed] Pastorius' first album, produced by Colomby and entitled Jaco Pastorius (1976), was a breakthrough album for the electric bass.[2] Many consider this to be the finest bass album ever recorded;[2] when it exploded onto the jazz scene it was widely praised by critics. The album also boasted a lineup of heavyweights in the jazz community at the time, who were essentially his stellar back up band, including Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, David Sanborn, Lenny White, Don Alias, and Michael Brecker among others.[9] Even legendary R&B singers Sam & Dave reunited to appear on the track "Come On, Come Over".[9]

[edit] Weather Report

Around the time of his solo album, he ran into keyboardist Josef Zawinul in Miami, where his band, Weather Report, were playing. According to Zawinul, Pastorius walked up to him after a concert one night and talked about the performance and said that it was all right but that he had expected more.[citation needed] He then went on to tell Zawinul that he was the greatest bass player in the world. An unamused Zawinul told him to "get the fuck outta [his] sight."[10] According to Milkowski's book, on that same evening, Jaco persisted and, according to Zawinul, reminded Zawinul of himself when he was a "brash young man" in Cannonball Adderley's band, which made Zawinul admire the young bassist. Zawinul asked for a demo tape from Pastorius, and thus began a series of correspondence between the two.

Pastorius entered Weather Report during the recording sessions for Black Market, and he became a vital part of the band both by virtue of the unique qualities of his bass playing, his skills as a composer and his exuberant showmanship on stage. His stage act and melodic, propulsive solos brought Weather Report a large new black audience; before his arrival the band had mostly pulled in white college fans.[citation needed]

One night before a gig, Zawinul offered Jaco a drink to loosen him up. Pastorius had never drunk before due to his father's own struggles with alcohol, but after two drinks, Zawinul said he got "strange. He started throwing things. I knew right away I had made a mistake."[7] Pastorius's drinking grew more out of control in the ensuing years, with Zawinul so furious during a Japanese tour in 1980 he was ready to fire Jaco.[citation needed] He called bassist Tony Levin, but he wasn't available. Before a replacement was found, Jaco showed up at Zawinul's door apologizing profusely, and Joe once again forgave him.[citation needed]

[edit] Guest appearances on albums

Pastorius guested on many albums by other artists; 1976 with Ian Hunter of Mott the Hoople fame, on All American Alien Boy with David Sanborn, Aynsley Dunbar, etc. Joni Mitchell's Hejira album, and a solo album by Al Di Meola are standouts, both released in 1976. Soon after that, Weather Report bass player Alphonso Johnson gave notice that he would be leaving to start his own band. Zawinul invited Pastorius to join the band, where he played alongside Joe and Wayne Shorter until 1983. During his time with Weather Report, Pastorius made his indelible mark on jazz music, notably by being featured on one of the most popular jazz albums of all time, the Grammy-nominated Heavy Weather. Not only did this album showcase Jaco's stunning bass playing, but he also received a co-producing credit with Joe Zawinul and even played drums on his self-composed "Teen Town."

During the course of his musical career, Pastorius played on dozens of recording sessions for other musicians, both in and out of jazz circles. Some of his most notable are four highly regarded albums with acclaimed singer/songwriter Joni Mitchell: Hejira (1976), Don Juan's Reckless Daughter (1977), Mingus (1979) and the live album Shadows and Light (1980). His influence was most dominant on Don Juan's Reckless Daughter, and many of the songs on that album seem to be composed using the bass as a melodic source of inspiration.

Near the end of his career, he guested on low-key releases by jazz artists such as guitarist Mike Stern, gypsy guitarist Biréli Lagrène, and drummer Brian Melvin. In 1985, he recorded an instructional video, Modern Electric Bass, hosted by bass legend Jerry Jemmott.

[edit] Projects

By the time he and Weather Report parted ways in early 1981, Jaco began pursuing his interest in creating a Big Band solo project named Word of Mouth, one that found its debut aurally on his second solo release, Word of Mouth. This 1981 album also boasted guest appearances by several distinguished jazz musicians; Herbie Hancock, Weather Report alumni Wayne Shorter and Peter Erskine, harmonica virtuoso Toots Thielemans and Hubert Laws. The album allowed Pastorius' songwriting to take some of the spotlight from his bass performance. It also showcased his production skills and ultimately, his ability to bring together a project that was recorded on both coasts of the United States, as well as in Belgium where he recorded Thielemans.

On his 30th birthday, December 1, 1981, he threw a party at a club in Fort Lauderdale, flew in some of the greats mentioned above, as well as Don Alias, Michael Brecker, and more. The event was recorded by his friend and engineer Peter Yianilos, who intended it as a birthday gift. After Jaco's passing Weather Report claimed the recordings as theirs and released it as the "The Birthday Concert".

He toured in 1982; a swing through Japan was the highlight, and it was at this time that bizarre tales of Jaco's deteriorating behavior first surfaced. He shaved his head, painted his face black and threw his bass into Hiroshima Bay at one point.[7] That tour was released in Japan as Twins I and Twins II and was condensed for an American release which was known as Invitation.

[edit] Behavior and health problems

In the early to mid-1980s, Pastorius began to experience increasingly severe mental health problems. These were worsened by drug and alcohol use, and he was eventually diagnosed as suffering from bipolar disorder. Although his on-stage and off-stage antics were already well-documented, his mental health and addiction issues exacerbated his already unusual and often bizarre behavior, and his musical performances suffered.

From 1984 to 1987 he played in various solo acts, mostly in Fort Lauderdale and New York City. His erratic behavior led to his becoming an outcast in the musical community. He was left to gig at various smaller venues, but as his behavior became too much, he would be banned at one club and move on to the next. He had to be pulled off stage during the 1984 Playboy Jazz Festival because of his drunkenness, prompting an apology to the crowd by MC Bill Cosby. By 1984, the Word of Mouth Big Band had also splintered.

In 1982, he managed to record a third solo album, which made it as far as some unpolished demo tapes, a steelpans-tinged release entitled Holiday for Pans, which once again showcased him as a composer and producer rather than a performer. Jaco did not play any of the bass parts on this album. He could not find a distributor for the album and the album was never released; however, it has since been widely bootlegged. In 2003, a cut from Holiday for Pans, entitled "Good Morning Anya", was included on Rhino Records' anthology Punk Jazz.

[edit] Death

After sneaking onstage at a Carlos Santana concert September 11, 1987, he was ejected from the premises, and he made his way to the Midnight Bottle Club in Wilton Manors, Florida.[11] After reportedly kicking in a glass door after being refused entrance to the club, he was engaged in a violent confrontation with the club bouncer, Luc Havan. Pastorius was hospitalized for multiple facial fractures and damage to his right eye and right arm, and had sustained irreversible brain damage.[citation needed] He fell into a coma and was put on life support.

There were initially encouraging signs that he would come out of his coma and recover, but a massive brain hemorrhage a few days later pointed to brain death. His family decided on a majority vote to remove him from life support, even though his second wife Ingrid was against the decision.[citation needed] Pastorius died on September 21, 1987, aged 35, at Broward General Medical Center in Fort Lauderdale. His heart continued to beat for three hours after the life support machine was disconnected.[citation needed]

In the wake of Pastorius' death, Havan, a karate expert, was charged with second degree murder, but later pled guilty to manslaughter, for which he served four months. Pastorius was buried at Our Lady Queen of Heaven Cemetery in North Lauderdale.[11]

[edit] Honors and tributes

Miles Davis honored the late bassist on his album Amandla with the Marcus Miller composition "Mr. Pastorius", as Jaco was an inspiration to Marcus Miller. Victor Wooten also honored Jaco on his album Soul Circus on the track "Bass Tribute", thanking Pastorius several times. Wooten and Steve Bailey's Bass Extremes includes the tracks "Glorius Pastorius", "Portrait of Tracy," and also a tribute to Jaco's interpretation of Charlie Parker's "Donna Lee" titled "Madonna Lee". The Pat Metheny Group also honored Jaco on their album Pat Metheny Group with the track "Jaco". This song was not specifically written for Pastorius. Metheny wrote the song and then realized that the main melody sounded a lot like Pastorius' "Come On, Come Over", and subsequently decided to name the tune for Pastorius.[citation needed]

John McLaughlin also honored Jaco on his album Industrial Zen with the song "For Jaco". English keyboard player Rod Argent includes a track titled "Pastorius Mentioned" on his 1979 Album Moving Home. Stuart Zender, the original bass player and founding member of Jamiroquai, cites Pastorius as one of his main influences. "With his sense of rhythm, melody and use of harmonics, Jaco pushed the envelope and transformed the way the electric bass guitar was played." Canadian bassist Alain Caron pays tribute to Pastorius by playing an upright bass version of "Donna Lee" on Uzeb's World Tour '90 album, and has mentioned that Pastorius was his biggest inspiration when it comes to playing fretless bass.

The song "Big Country", by Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, contains the opening lick from Jaco's "Continuum". On November 28, 2007, the Oakland Park City Commission unanimously voted to name the city's new downtown park after Pastorius. Jaco's hometown celebrated its most famous artist with a tremendous honor: a living memorial with a focus on the arts. A 2-1/2 year grassroots effort by loyal south Florida fans finally came to fruition. Now south Florida residents and Jaco fans worldwide will have a place to reflect upon and enjoy the legacy of this music giant. There are also plans to incorporate Jaco's name and story into the City's various performing arts events. Bassists Tetsuo Sakurai, Kenji Hino, Quagero Imazawa, Koichi Osamu, Kiichiro Komobuchi, and Akira, all of Japan, released a tribute album entitled Play Jaco: A Tribute To Jaco Pastorius in 2006 under the artist name Japanese Top Bass Guitarists.

On December 2, 2007, the day after what would have been Pastorius' 56th birthday, a concert called "A Tribute to Jaco Pastorius" was held at The Broward Center for the Performing Arts in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, featuring performances by the award-winning Jaco Pastorius Big Band with special guest appearances by Peter Erskine, Randy Brecker, Bob Mintzer, David Bargeron, Jimmy Haslip, Gerald Veasley, Jaco's sons John and Julius Pastorius, Jaco's daughter Mary Pastorius, Ira Sullivan, Bobby Thomas, Jr., and Dana Paul. Also shown were exclusive home movies and rare concert footage as well as video appearances by Pat Metheny, Joni Mitchell, and other luminaries from Jaco's life. Almost 20 years after Jaco's death, Fender released the Jaco Pastorius Jazz Bass, a fretless instrument from its Artist Series.

JACO PASTORIUS PARK, 4100 North Dixie Highway (38th & Dixie), Oakland Park, Florida, established November 27, 2007, ribbon cutting ceremony was December 1, 2008. *Jaco Pastorius Park

[edit] Awards

Apart from his career in the jazz fusion band Weather Report, Jaco had two Grammy Award nominations for his self-titled debut album.[2] He was inducted into Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame in 1988, one of only four bassists to be so honored (the others being Charles Mingus, Milt Hinton, and Ray Brown), and the only electric bassist to receive this distinction.

[edit] Playing style

[edit] Technique

|

|||||

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. | |||||

The "Jaco growl" is obtained by using the bridge pickup exclusively, and plucking the strings right above the bridge pickup. Pastorius used natural and false harmonics to extend the range of the bass (exemplified in the bass solo masterpiece Portrait of Tracy from his eponymous album) and could achieve a horn-like tone through his playing technique. His playing techniques earned him accolades both from the critics and his audiences. He used finger-style playing exclusively, and was not fond of the slap bass style of many funk and R&B bassists of the time. His playing has been described by those who know him to be fast and showy, but always in time with the "groove."

[edit] Equipment

[edit] Basses

Pastorius was most identified by his use of two well-worn Fender Jazz Basses from the early 1960s: A 1960 fretted, and a 1962 fretless. The fretless, known by Jaco as the "Bass of Doom", was originally a fretted bass (at the time Fender did not manufacture fretless Jazz Basses) from which he removed the frets with a butter knife and used wood filler to fill in the grooves where the frets had been, along with the holes created where chunks of the fretboard had been taken out.[12] Jaco then sanded down the fingerboard, and applied several coats of marine epoxy (Petit's Poly-poxy) to prevent the rough Rotosound RS-66 roundwound bass strings he used from eating into the bare wood. Even though he played both the fretted and the fretless basses frequently, he preferred the fretless, because he felt frets were a hindrance, once calling them "speed bumps". However, he said in the instructional video that he never practiced with the fretless because the strings "chew the neck up." Both of his Fender basses were stolen shortly before he entered Bellevue hospital in 1986. In 1993, one of the basses resurfaced in a New York City music shop, with the distinctive letter P written between the two pickups. In 2008, the 1962 fretless "Bass of Doom" also turned up in good condition in New York.[13]

[edit] Amplification, effects, and strings

Jaco used the "Variamp" EQ (equalization) controls on his two Acoustic 360 amplifiers (made by the Acoustic Control Corporation of Van Nuys, California) to boost the midrange frequencies, thus accentuating the natural growling tone of his fretless passive Fender Jazz Bass and roundwound string combination. His tone was also colored by the use of a rackmount MXR digital delay unit that fed a second Acoustic amp rig.

He often used Hartke cabinets because of their characteristic aluminum speaker cones (as opposed to paper speaker cones). These gave his tone a bright, clean clarity. He typically used the delay in a chorus-like mode, providing a shimmering stereo doubling effect. He would often use the fuzz control built in on the Acoustic 361. For the bass solo "Slang" on the 8:30 album, Jaco used the MXR digital delay to layer and loop a chordal figure and then he soloed over it. Jaco used Rotosound strings. [14]

[edit] Biography controversy

In 1995, jazz author Bill Milkowski published Jaco: The Extraordinary And Tragic Life of Jaco Pastorius. 'The World's Greatest Bass Player'. The book was filled with interviews with leading jazz musicians, music executives and Jaco's brother, but Milkowski's first-hand experiences with Jaco were toward the end of his life, when he had deteriorated badly. Jaco's second wife Ingrid has taken issue with many of the claims made in the book, stating that they either did not happen or happened very differently.[15] Guitarist Pat Metheny, with whom Pastorius worked on several albums, leveled his own criticism in the liner notes of the reissue of Jaco's first album, calling it "a horribly inaccurate, botched biography." When the softcover edition of Jaco was published, one correction was made concerning an incident supposedly involving Jaco's daughter Mary, but the rest remains unchanged.

[edit] Discography

| Solo | Weather Report | Collaboration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Album | Artist | |||

| 1974 | Pat Metheny, Ditmas, Bley | |||

| 1975 | Pat Metheny | |||

| 1976 | Ian Hunter Joni Mitchell |

|||

| 1977 |

|

Joni Mitchell Albert Mangelsdorff, Alphonse Mouzon |

||

| 1978 |

|

Flora Purim Herbie Hancock |

||

| 1979 |

|

Joni Mitchell Joni Mitchell Michel Colombier John McLaughlin, Tony Williams |

||

| 1980 | Herbie Hancock | |||

| 1981 | ||||

| 1982 | ||||

| 1983 |

|

|||

| 1984 |

|

Essence | ||

| 1985 |

|

Deadline | ||

| 1986 |

|

|

Brian Melvin Biréli Lagrène Mike Stern The Brian Melvin Trio Brian Melvin |

|

[edit] References

- ^ a b c Ginell, Richard S. "Jaco Pastorius biography". Allmusic. All Media Guide, LLC. http://www.allmusic.com/cg/amg.dll?p=amg&sql=11:jifoxqy5ldje~T1. Retrieved on June 24 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Jaco Pastorius" (html). Jacopastorius.co.uk. http://www.jacopastorius.co.uk/index2.html. Retrieved on June 27 2007.

- ^ a b c "Radio 3 Jazz Profiles: Jaco Pastorius". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio3/jazz/profiles/jaco_pastorius.shtml. Retrieved on 2008-03-04.

- ^ a b Pastorius, Ingrid. "Frequently asked questions" (html). Jaco Pastorius cyber nest. http://www.jacop.net/faq.html. Retrieved on June 24 2007.

- ^ Pat Jordan, "Who Killed Jaco Pastorius?" Gentlemen's Quarterly, May 1988.

- ^ a b Milkowski, Bill. Jaco: The Extraordinary and Tragic Life of Jaco Pastorius, "The World's Greatest Bass Player". Backbeat Books, pp. 23.

- ^ a b c d e f ibid

- ^ a b "Jaco Pastorius: 20 Years Later". NPR. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=14578299&sc=nl&cc=mn-20071007. Retrieved on 2008-03-04.

- ^ a b "Jaco Pastorius credits". Allmusic. All Media Guide, LLC. http://www.allmusic.com/cg/amg.dll?p=amg&sql=10:0xfrxqrgldje~T2. Retrieved on June 27 2007.

- ^ Pat Jordan, "Who Killed Jaco Pastorius?" Gentlemen's Quarterly, May 1988.

- ^ a b Stanton, Scott (2003). The Tombstone Tourist: Musicians, p. 195. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0743463307.

- ^ Bradman, E.E. (2002-01-01). "Evolution Of A Genius". Bass Writer (Basswriter.com). http://www.basswriter.com/journalism/bpstories/Web-Jaco.doc. Retrieved on 2008-10-27.

- ^ Jisi, Chris (March 2008). "Jaco’s 1962 Fender Jazz Bass “Bass of Doom” Found!". Bass Player Online (New Bay Media, LLC). http://www.bassplayer.com/article/jacos-1962-fender/mar-08/34267. Retrieved on 2009/01/17.

- ^ http://www.jacopastorius.com/features/interviews/portrait.asp - Retrieved on 15/07/08.

- ^ http://www.jacop.net/book2.html

[edit] External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Jaco Pastorius |

- Official website

- Jaco Pastorius discography at MusicBrainz

- Jacob Pastorius profile at NNDB

- Pastorius family site

- Jaco Pastorius Unissued Live Recordings Discography

- Jaco's grave

- Interview with Ingrid Pastorius

- [1] Bass Of Doom Headstock, Damaged.

- [2] Bass Of Doom Fingerboard, Epoxy Coated. Serial Numbered.

- [3] Jaco eating french-fries in the dressing room of the Lone Star Cafe, NYC march 1986.