Osiris

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. Please improve this article if you can. (July 2008) |

| Osiris | ||||

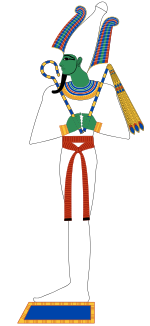

Osiris, lord of the dead. His green skin symbolizes re-birth. |

||||

| God of the afterlife | ||||

| Name in hieroglyphs |

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major cult center | Abydos | |||

| Symbol | Crook and flail | |||

| Parents | Geb and Nut | |||

| Siblings | Isis, Set | |||

| Consort | Isis | |||

| Children | Horus | |||

Osiris (Greek language, also Usiris; the Egyptian language name is variously transliterated Asar, Aser, Ausar, Ausir, Wesir, or Ausare) was an Egyptian god, usually called the god of the Afterlife.

Osiris is one of the oldest gods for whom records have been found; one of the oldest known attestations of his name is on the Palermo Stone of around 2500 BC. He was widely worshiped until the suppression of the Egyptian religion during the Christian era.[1][2]The information we have on the myths of Osiris is derived from allusions contained in the Pyramid Texts (ca. 2400 BC), later New Kingdom source documents such as the Shabaka Stone and the Contending of Horus and Seth, and much later, in narrative style from the writings of Greek authors including Plutarch[3] and Diodorus Siculus.[4]

Osiris was not only a merciful judge of the dead in the afterlife, but also the underworld agency that granted all life, including sprouting vegetation and the fertile flooding of the Nile River. The Kings of Egypt were associated with Osiris in death — as Osiris rose from the dead they would, in union with him, inherit eternal life through a process of imitative magic. By the New Kingdom all people, not just pharaohs, were believed to be associated with Osiris at death if they incurred the costs of the assimilation rituals.[5]

Osiris was at times considered the oldest son of the Earth god, Geb,[6] and the sky goddess, Nut as well as being brother and husband of Isis, with Horus being considered his posthumously begotten son.[6]

Osiris was later associated with the name Khenti-Amentiu, which means 'Foremost of the Westerners' a reference to his kingship in the land of the dead.[7]

Contents |

[edit] Appearance

Osiris was usually depicted as a green (the color of rebirth) or black (alluding to the fertility of the Nile floodplain) complexioned pharaoh in mummiform.[8] He wears the Atef crown, a form of the white crown of upper Egypt with a plume of feathers to either side. Typically he was also depicted holding the crook and flail which signified divine authority in Egyptian pharaohs, but which were originally unique to Osiris and his own origin-gods (see below), and his feet and lower body were wrapped, as though already partly mummified.

[edit] Early mythology

When the Ennead and Ogdoad cosmogenies became merged, with the identification of Ra as Atum (Atum-Ra), gradually Anubis (Ogdoad system) was replaced by Osiris, whose cult had become more significant. Anubis was said to have given way to Osiris out of respect, and, as an underworld deity. Anubis was Set's son in some versions, but because Set became god of evil, he was subsequently identified as being Osiris' son. Abydos, which had been a strong centre of the cult of Anubis, became a centre of the cult of Osiris. Because Isis, Osiris' wife and sister, represented life in the Ennead, it was considered somewhat inappropriate for her to be the mother of a god associated with death such as Anubis, and so instead, it was usually said that Nephthys, the other of the two female children of Geb and Nut, was his mother.

[edit] Father of Horus

Later, when Hathor's identity (from the Ogdoad) was assimilated into that of Isis, Horus, who had been Isis' husband (in the Ogdoad), became considered her son, and thus, since Osiris was Isis' husband (in the Ennead), Osiris also became considered Horus' father. Attempts to explain how Osiris, a god of the dead, could give rise to Horus, who was thought to be living, led to the development[citation needed] of the Myth of Osiris and Isis, which became a central myth in Egyptian mythology. The myth described Osiris as having been killed by his brother Set who wanted Osiris' throne. Isis briefly brought Osiris back to life by use of a spell that she learned from her father. This spell gave her time to become pregnant by Osiris before he again died. Isis later gave birth to Horus. As such, since Horus was born after Osiris' resurrection, Horus became thought of as representing new beginnings, and vanquished Set. This combination, Osiris-Horus, was therefore a life-death-rebirth deity, and thus associated with the new harvest each year. Afterward, Osiris became known as the Egyptian god of the dead, Isis became known as the Egyptian goddess of the children, and Horus became known as the Egyptian god of the sky.

Ptah-Seker (who resulted from the identification of Ptah as Seker), who was god of re-incarnation, thus gradually became identified with Osiris, the two becoming Ptah-Seker-Osiris (rarely known as Ptah-Seker-Atum, although this was just the name, and involved Osiris rather than Atum). As the sun was thought to spend the night in the underworld, and subsequently be re-incarnated, as both king of the underworld, and god of reincarnation, Ptah-Seker-Osiris was identified.

[edit] Ram god

| Banebdjed (b3-nb-ḏd) in hieroglyphs |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Since Osiris was considered dead, as god of the dead, Osiris' soul, or rather his Ba, was occasionally worshipped in its own right, almost as if it were a distinct god, especially so in the Delta city of Mendes. This aspect of Osiris was referred to as Banebdjed (also spelt Banebded or Banebdjedet, which is technically feminine) which literally means The ba of the lord of the djed, which roughly means The soul of the lord of the pillar of stability. The djed, a type of pillar, was usually understood as the backbone of Osiris, and, at the same time, as the Nile, the backbone of Egypt. The Nile, supplying water, and Osiris (strongly connected to the vegetation) who died only to be resurrected represented continuity and therefore stability. As Banebdjed, Osiris was given epithets such as Lord of the Sky and Life of the (sun god) Ra, since Ra, when he had become identified with Atum, was considered Osiris' ancestor, from whom his regal authority was inherited. Ba does not, however, quite mean soul in the western sense, and also has to do with power, reputation, force of character, especially in the case of a god. Since the ba was associated with power, and also happened to be a word for ram in Egyptian, Banebdjed was depicted as a ram, or as Ram-headed. A living, sacred ram, was even kept at Mendes and worshipped as the incarnation of the god, and upon death, the rams were mummified and buried in a ram-specific necropolis.

As regards the association of Osiris with the ram, the god's traditional crook and flail are of course the instruments of the shepherd, which has suggested to some scholars also an origin for Osiris in herding tribes of the upper Nile. The crook and flail were originally symbols of the minor agricultural deity Anedijti, and passed to Osiris later. From Osiris, they eventually passed to Egyptian kings in general as symbols of divine authority.

In Mendes, they had considered Hatmehit, a local fish-goddess, as the most important deity, and so when the cult of Osiris became more significant, Banebdjed was identified in Mendes as deriving his authority from being married to Hatmehit. Later, when Horus became identified as the child of Osiris (in this form Horus is known as Harpocrates in Greek and Har-pa-khered in Egyptian), Banebdjed was consequently said to be Horus' father, as Banebdjed is an aspect of Osiris.

In occult writings, Banebdjed is often called the goat of Mendes, and identified with Baphomet[citation needed]; the fact that Banebdjed was a ram (sheep), not a goat, is apparently overlooked.

[edit] Mythology

The cult of Osiris (who was a god chiefly of regeneration and re-birth) had a particularly strong interest toward the concept of immortality. Plutarch recounts one version of the myth surrounding the cult in which Set (Osiris' brother) fooled Osiris into getting into a box, which he then shut, had sealed with lead, and threw into the Nile (sarcophagi were based on the box in this myth). Osiris' wife, Isis, searched for his remains until she finally found him embedded in a tree trunk, which was holding up the roof of a palace in Byblos on the Phoenician coast. She managed to remove the coffin and open it, but Osiris was already dead. She used a spell she had learned from her father and brought him back to life so he could impregnate her. After they finished, he died again, so she hid his body in the desert. Months later, she gave birth to Horus. While she was off raising him, Set had been out hunting one night, and he came across the body of Osiris. Enraged, he tore the body into fourteen pieces and scattered them throughout the land. Isis gathered up all the parts of the body, less the phallus which was eaten by a fish thereafter considered taboo by the Egyptians, and bandaged them together for a proper burial. The gods were impressed by the devotion of Isis and thus resurrected Osiris as the god of the underworld. Because of his death and resurrection, Osiris is associated with the flooding and retreating of the Nile and thus with the crops along the Nile valley.

Diodorus Siculus gives another version of the myth in which Osiris is described as an ancient king who taught the Egyptians the arts of civilization, including agriculture. Osiris is murdered by his evil brother Set, whom Diodorus associates with the evil Typhon ("Typhonian Beast") of Greek mythology. Typhon divides the body into twenty six pieces which he distributes amongst his fellow conspirators in order to implicate them in the murder. Isis and Horus avenge the death of Osiris and slay Typhon. Isis recovers all the parts of Osiris body, less the phallus, and secretly buries them. She made replicas of them and distributed them to several locations which then became centres of Osiris worship.[9][10]

The tale of Osiris becoming fish-like is cognate with the story the Greek shepherd god Pan becoming fish like from the waist down in the same river Nile after being attacked by Typhon (see Capricornus). This attack was part of a generational feud in which both Zeus and Dionysus were dismembered by Typhon, in a similar manner as Osiris was by Set in Egypt.[citations needed]

Osiris was viewed as the one who died to save the many, who rose from the dead, the first of a long line that has significantly affected man's view of the world and expections of an afterlife.[11]

Osiris was linked to the constellation Orion (Sahu in Egyptian).

[edit] Passion and resurrection

Plutarch and others have noted that the sacrifices to Osiris were “gloomy, solemn, and mournful...” (Isis and Osiris, 69) and that the great mystery festival, celebrated in two phases, began at Abydos on the 17th of Athyr[12] (November 13) commemorating the death of the god, which is also the same day that grain was planted in the ground. “The death of the grain and the death of the god were one and the same: the cereal was identified with the god who came from heaven; he was the bread by which man lives. The resurrection of the God symbolized the rebirth of the grain.” (Larson 17) The annual festival involved the construction of “Osiris Beds” formed in shape of Osiris, filled with soil and sown with seed.[13] The germinating seed symbolized Osiris rising from the dead. An almost pristine example was found in the tomb of Tutankhamun by Howard Carter.[14]

The first phase of the festival was a public drama depicting the murder and dismemberment of Osiris, the search of his body by Isis, his triumphal return as the resurrected god, and the battle in which Horus defeated Set. This was all presented by skilled actors as a literary history, and was the main method of recruiting cult membership. According to Julius Firmicus Maternus of the fourth century, this play was re-enacted each year by worshippers who “beat their breasts and gashed their shoulders.... When they pretend that the mutilated remains of the god have been found and rejoined...they turn from mourning to rejoicing.” (De Errore Profanorum).

The passion of Osiris is reflected in his name 'Wenennefer" ("the one who continues to be perfect"), which also alludes to his post mortem power.[15]

Scholars such as E.A. Wallis Budge have suggested possible connections or parallels in Osiris' resurrection story with those found in Christianity: "The Egyptians of every period in which they are known to us believed that Osiris was of divine origin, that he suffered death and mutilation at the hands of the powers of evil, that after a great struggle with these powers he rose again, that he became henceforth the king of the underworld and judge of the dead, and that because he had conquered death the righteous also might conquer death...In Osiris the Christian Egyptians found the prototype of Christ, and in the pictures and statues of Isis suckling her son Horus, they perceived the prototypes of the Virgin Mary and her child."[16]

[edit] I-Kher-Nefert stele

Much of the extant information about the Passion of Osiris can be found on a stele at Abydos erected in the 12th Dynasty by I-Kher-Nefert (also Ikhernefert), possibly a priest of Osiris or other official during the reign of Senwosret III (Pharaoh Sesostris, about 1875 BC). The Passion Plays were held in the last month of the inundation (the annual Nile flood), coinciding with Spring, and held at Abydos/Abedjou which was the traditional place where the body of Osiris/Wesir drifted ashore after having been drowned in the Nile.[17] The part of the myth recounting the chopping up of the body into 14 pieces by Set is not recorded until later by Plutarch. Some elements of the ceremony were held in the temple, while others involved public participation in a form of theatre. The Stela of I-Kher-Nefert recounts the programme of events of the public elements over the five days of the Festival:

- The First Day, The Procession of Wepwawet: A mock battle is enacted during which the enemies of Osiris are defeated. A procession is led by the god Wepwawet ("opener of the way").

- The Second Day, The Great Procession of Osiris: The body of Osiris is taken from his temple to his tomb. The boat he is transported in, the "Neshmet" bark, has to be defended against his enemies.

- The Third Day, Osiris is Mourned and the Enemies of the Land are Destroyed.

- The Fourth Day, Night Vigil: Prayers and recitations are made and funeral rites performed.

- The Fifth Day, Osiris is Reborn: Osiris is reborn at dawn and crowned with the crown of Ma'at. A statue of Osiris is brought to the temple.[17]

[edit] Wheat and clay rituals

Contrasting with the public "theatrical" ceremonies sourced from the I-Kher-Nefert stele, more esoteric ceremonies were performed inside the temples by priests witnessed only by initiates. Plutarch mentions that two days after the beginning of the festival “the priests bring forth sacred chest containing a small golden coffer, into which they pour some potable water...and a great shout arises from the company for joy that Osiris is found (or resurrected). Then they knead some fertile soil with the water...and fashion therefrom a crescent-shaped figure, which they cloth and adorn, this indicating that they regard these gods as the substance of Earth and Water.” (Isis and Osiris, 39). Yet even he was obscure, for he also wrote, “I pass over the cutting of the wood” opting to not describe it since he considered it most sacred (Ibid. 21). In the Osirian temple at Denderah, an inscription (translated by Budge, Chapter XV, Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection) describes in detail the making of wheat paste models of each dismembered piece of Osiris to be sent out to the town where each piece was discovered by Isis. At the temple of Mendes, figures of Osiris are made from wheat and paste placed in a trough on the day of the murder, then water added for several days, when finally the mixture was kneaded into a mold of Osiris and taken to the temple and buried (the sacred grain for these cakes only grown in the temple fields). Molds are made from wood of a red tree in the forms of the sixteen dismembered parts of Osiris, cakes of divine bread made from each mold, placed in a silver chest and set near the head of the god, the inward parts of Osiris as described in the Book of the Dead (XVII). On the first day of the Festival of Ploughing, where the goddess Isis appears in her shrine where she is stripped naked, Paste made from the grain is placed in her bed and moistened with water, representing the fecund earth. All of these sacred rituals were climaxed by the eating of sacramental god, the eucharist by which the celebrants were transformed, in their persuasion, into replicas of their god-man (Larson 20).

[edit] Osiris-Dionysus

By the Hellenic era, Greek awareness of Osiris had grown, and attempts had been made to merge Greek philosophy, such as Platonism, and the cult of Osiris (especially the myth of his resurrection), resulting in a new mystery religion. Gradually, this became more popular, and was exported to other parts of the Greek sphere of influence. However, these mystery religions valued the change in wisdom, personality, and knowledge of fundamental truth, rather than the exact details of the acknowledged myths on which their teachings were superimposed. Thus in each region that it was exported to, the myth was changed to be about a similar local god, resulting in a series of gods, who had originally been quite distinct, but who were now syncretisms with Osiris. These gods became known as Osiris-Dionysus.

[edit] Serapis

Eventually, in Egypt, the Hellenic pharaohs decided to produce a deity that would be acceptable to both the local Egyptian population, and the influx of Hellenic visitors, to bring the two groups together, rather than allow a source of rebellion to grow. Thus Osiris was identified explicitly with Apis, really an aspect of Ptah, who had already been identified as Osiris by this point, and a syncretism of the two was created, known as Serapis, and depicted as a standard Greek god.

The early Alexanderian Christian community appears to have been rather syncretic in their worship of Serapis and Jesus and would prostrate themselves without distinction between the two.[18] A letter ascribed in the Augustan History[19] to the Emperor Hadrian refers to the worship of Serapis by residents of Egypt who described themselves as Christians, and Christian worship by those claiming to worship Serapis, suggesting a great confusion of the cults and practices:

The land of Egypt, the praises of which you have been recounting to me, my dear Servianus, I have found to be wholly light-minded, unstable, and blown about by every breath of rumour. There those who worship Serapis are, in fact, Christians, and those who call themselves bishops of Christ are, in fact, devotees of Serapis. There is no chief of the Jewish synagogue, no Samaritan, no Christian presbyter, who is not an astrologer, a soothsayer, or an anointer. Even the Patriarch himself, when he comes to Egypt, is forced by some to worship Serapis, by others to worship Christ. (Augustan History, Firmus et al. 8)

[edit] Destruction

The cult of Osiris continued up until the 6th century AD on the island of Philae in Upper Nile. The Theodosian decree (in about 380 AD) to destroy all pagan temples and force worshipers to accept Christianity was not enforced there.The worship of Isis and Osiris was allowed to continue at Philae until the time of Justinian. This toleration was due to an old treaty made between the Blemyes-Nobadae and Diocletian. Every year they visited Elaphantine and at certain intervals took the image of Isis up river to the land of the Blemyes for oracular purposes before returning it. Justinian would not tolerate this and sent Narses to destroy the sanctuaries, with the priests being arrested and the divine images taken to Constantinople.[20]

[edit] See also

[edit] Notes

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia: Theodosius I

- ^ ”History of the Later Roman Empire from the Death of Theodosius I. to the Death of Justinian”, The Suppression of Paganism – ch22, p371,John Bagnell Bury, Courier Dover Publications, 1958, ISBN 0486203999

- ^ "Isis and Osiris", Plutarch, translated by Frank Cole Babbitt, 1936, Vol 5 Loeb Classical Library.[1]

- ^ "The Historical Library of Diodorus Siculus", Vol 1, translated by G. Booth, 1814.[2]

- ^ "Man, Myth and Magic", Osiris, Vol 5 p2087-88, S.G.F Brandon, BPC Publishing, 1971.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The complete gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 105. ISBN 0-500-05120-8.

- ^ "How to Read Egyptian Heiroglyphs", Mark Collier & Bill Manley, British Museum Press, p41, 1998, ISBN 0 7141 1910 5

- ^ "How to Read Egyptian Heiroglyphs", Mark Collier & Bill Manley, British Museum Press, p42, 1998, ISBN 0 7141 1910 5

- ^ "Osiris", Man, Myth & Magic, S.G.F Brandon, Vol5 P2088, BPC Publishing.

- ^ "The Historical Library of Diodorus Siculus", translated by George Booth 1814. retrieved 3 June 2007.[3]

- ^ Davis, Nigel. "Human Sacrifice", Wlliam Morrow & Sons, ch2,1981

- ^ Plutarch. "Section 13". Isis and Osiris. pp. 356C–D. http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Moralia/Isis_and_Osiris*/A.html#T356c. Retrieved on 2007-01-21.

- ^ Britannica Ultimate Edition 2003 DVD

- ^ Osiris Bed, Burton photograph p2024, The Griffith Institute.[4]

- ^ "How to Read Egyptian Heiroglyphs", Mark Collier & Bill Manley, British Museum Press, p42, 1998, ISBN 0 7141 1910 5

- ^ E.A Wallis Budge, "Egyptian Religion",Ch2,ISBN 0-14-019017-1

- ^ a b ancientworlds.net - the passion plays of osiris

- ^ "Two Thousand Years of Coptic Christianity", Otto Friedrich August Meinardus, American Univ in Cairo Press, 2002, p143, ISBN 9774247574A

- ^ In modern times most scholars read this work as a piece of "deliberate mystification" written much later than it's purported date, however the "fundamentalist view" still has distinguished support see: "The Cambridge History of Classical Literature", E. J. Kenney, Wendell Vernon Clausen, p43, Cambridge University Press, 1983,ISBN 0521273714

- ^ ”History of the Later Roman Empire from the Death of Theodosius I. to the Death of Justinian”, The Suppression of Paganism – ch22, p371,John Bagnell Bury, Courier Dover Publications, 1958, ISBN 0486203999

[edit] References

- Martin A. Larson, The Story of Christian Origins (1977, 711 pp. ISBN 0883310902 ).

[edit] External links

- Ancient Egyptian God Osiris

- The Influence of the Mystery Religions on Christianity by Martin Luther King Jr.

|

||||||||||||||||||||

![V30 [nb] nb](/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_V30.png)

![R11 [Dd] Dd](/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_R11.png)

![O49 [niwt] niwt](/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_O49.png)