Camera obscura

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

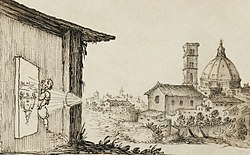

The camera obscura (Latin veiled chamber) is an optical device used, for example, in drawing or for entertainment. It is one of the inventions leading to photography. The principle can be demonstrated with a box with a hole in one side (the box may be room-sized, or hangar sized). Light from a scene passes through the hole and strikes a surface where it is reproduced, in color, and upside-down. The image's perspective is accurate. The image can be projected onto paper, which when traced can produce a highly accurate representation.

Using mirrors, as in the 18th century overhead version (illustrated in the Discovery and Origins section below), it is possible to project a right-side-up image. Another more portable type is a box with an angled mirror projecting onto tracing paper placed on the glass top, the image upright as viewed from the back.

As a pinhole is made smaller, the image gets sharper, but the projected image becomes dimmer. With too small a pinhole the sharpness again becomes worse due to diffraction. Some practical camera obscurae use a lens rather than a pinhole because it allows a larger aperture, giving a usable brightness while maintaining focus. (See pinhole camera for construction information.)

Contents |

[edit] Discovery and origins

The first mention of the principles behind the pinhole camera, a precursor to the camera obscura, belongs to Mozi (470 BC to 390 BC), a Chinese philosopher and the founder of Mohism.[1] The Mohist tradition is unusual in Chinese thought because it is concerned with developing principles of logic. The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384 to 322 BC) understood the optical principle of the pinhole camera. He viewed the crescent shape of a partially eclipsed sun projected on the ground through the holes in a sieve, and the gaps between leaves of a plane tree.

The first camera obscura was later built by Arab scientist Abu Ali Al-Hasan Ibn al-Haitham, born in Basra (965-1039 AD), known in the West as Alhacen or Alhazen, who carried out practical experiments on optics in his Book of Optics.[2] Most of his professional career took place in Cairo, where he was summoned for his first engineering task of regulating the flow of the Nile river. In his experiments, Ibn Al-Haitham used the term “Al-Bayt al-Muthlim, translated in English as dark room. In the experiment he undertook, in order to establish that light travels in time and with speed, he says: "If the hole was covered with a curtain and the curtain was taken off, the light traveling from the hole to the opposite wall will consume time." He reiterated the same experience when he established that light travels in straight lines. A revealing experiment introduced the camera obscura in studies of the half-moon shape of the sun's image during eclipses which he observed on the wall opposite a small hole made in the window shutters. In his famous essay "On the form of the Eclipse" (Maqalah-fi-Surat-al-Kosuf) he commented on his observation "The image of the sun at the time of the eclipse, unless it is total, demonstrates that when its light passes through a narrow, round hole and is cast on a plane opposite to the hole it takes on the form of a moon-sickle”.

In his experiment of the sun light he extended his observation of the penetration of light through the pinhole to conclude that when the sun light reaches and penetrates the hole it makes a conic shape at the points meeting at the pinhole, forming later another conic shape reverse to the first one on the opposite wall in the dark room. This happens when sun light diverges from point “ﺍ” until it reaches an aperture and is projected through it onto a screen at the luminous spot. Since the distance between the aperture and the screen is insignificant in comparison to the distance between the aperture and the sun, the divergence of sunlight after going through the aperture should be insignificant. In other words, should be about equal to. However, it is observed to be much greater when the paths of the rays which form the extremities of are retraced in the reverse direction, it is found that they meet at a point outside the aperture and then diverge again toward the sun as illustrated in figure 1. This an early accurate description of the Camera Obscura phenomenon.

With a second hole the image is doubled. when the first camera was presented it was thought of as witchcraft and the person who showed it was jailed

Light generally travels in a straight line. When rays reflected from a bright subject pass through the small hole in thin material they do not scatter but cross and reform as an upside down image on a flat white surface held parallel to the surface through which the hole has been pierced. Ibn Al-Haitham established that the smaller the hole is, the clearer the picture is.

[edit] History

Although the pinhole camera and camera obscura are credited to Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen, 965-1039),[2] for the first clear description[3] and correct analysis[4] of the device and for first describing how an image is formed in the eye using the camera obscura as an analogy, primitive forms of a camera obscura were known to earlier scholars since the time of Mozi and Aristotle. Euclid's Optics (ca 300 BC), presupposed the camera obscura as a demonstration that light travels in straight lines.[5] When Ibn al-Haytham began experimenting with the camera obscura phenomenon, he himself stated, with respect to the camera obscura phenomenon, Et nos non inventimus ita, "we did not invent this".[6]

In the 4th century BC, Aristotle noted that "sunlight traveling through small openings between the leaves of a tree, the holes of a sieve, the openings wickerwork, and even interlaced fingers will create circular patches of light on the ground." In the 4th century AD, Theon of Alexandria observed how "candlelight passing through a pinhole will create an illuminated spot on a screen that is directly in line with the aperture and the center of the candle." In the 9th century, Al-Kindi (Alkindus) demonstrated that "light from the right side of the flame will pass through the aperture and end up on the left side of the screen, while light from the left side of the flame will pass through the aperture and end up on the right side of the screen." While these earlier scholars described the effects of a single light passing through a pinhole, none of them suggested that what is being projected onto the screen is an image of everything on the other side of the aperture. Ibn al-Haytham's Book of Optics (1021) was the first to demonstrate this with his lamp experiment where several different light sources are arranged across a large area, and he was thus the first scientist to successfully project an entire image from outdoors onto a screen indoors with the camera obscura.[7]

Several decades after Ibn al-Haytham's death, the Song Dynasty Chinese scientist Shen Kuo (1031–1095) experimented with camera obscura, and was the first to apply geometrical and quantitative attributes to it in his book of 1088 AD, the Dream Pool Essays.[8] However, Shen Kuo alluded to the fact that the Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang written in about 840 AD by Duan Chengshi (d. 863) during the Tang Dynasty (618–907) mentioned inverting the image of a Chinese pagoda tower beside a seashore.[8] In fact, Shen makes no assertion that he was the first to experiment with such a device.[8] Shen wrote of Cheng's book: "[Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang] said that the image of the pagoda is inverted because it is beside the sea, and that the sea has that effect. This is nonsense. It is a normal principle that the image is inverted after passing through the small hole."[8]

In 13th-century England Roger Bacon described the use of a camera obscura for the safe observation of solar eclipses.[9] Its potential as a drawing aid may have been familiar to artists by as early as the 15th century; Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519 AD) described camera obscura in Codex Atlanticus. Johann Zahn's Oculus Artificialis Teledioptricus Sive Telescopium was published in 1685. This work contains many descriptions and diagrams, illustrations and sketches of both the camera obscura and of the magic lantern.

The Dutch Masters, such as Johannes Vermeer, who were hired as painters in the 17th century, were known for their magnificent attention to detail. It has been widely speculated that they made use of such a camera, but the extent of their use by artists at this period remains a matter of considerable controversy, recently revived by the Hockney-Falco thesis. The term "camera obscura" was first used by the German astronomer Johannes Kepler in 1604.[10]

Early models were large; comprising either a whole darkened room or a tent (as employed by Johannes Kepler). By the 18th century, following developments by Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke, more easily portable models became available. These were extensively used by amateur artists while on their travels, but they were also employed by professionals, including Paul Sandby, Canaletto and Joshua Reynolds, whose camera (disguised as a book) is now in the Science Museum (London). Such cameras were later adapted by Louis Daguerre and William Fox Talbot for creating the first photographs.

[edit] Tourist attractions

Some camera obscura have been built as tourist attractions, often taking the form of a large chamber within a high building that can be darkened so that a 'live' panorama of the world outside is projected onto a horizontal surface through a rotating lens. Although few now survive, examples (many of recent construction) can be found at the following locations:

- The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in the United States

- Turin in Italy- at the Cinema Museum inside the Mole Antonelliana by Antonelli.

- Edinburgh in Scotland - See the Camera Obscura & World of Illusions site. This is an original Victorian Camera Obscura, open since 1853.

- Grahamstown in South Africa

- Johannesburg in South Africa

- Pretoria in South Africa

- Cape Town in South Africa

- the Observatory in Bristol, England

- Portslade village in Sussex, England

- Eastbourne Pier in Sussex, England

- Kentwell Hall, Long Melford, Suffolk, England

- Aberystwyth and Portmeirion in Wales

- Kirriemuir, Dumfries and Edinburgh in Scotland

- Douglas, Isle of Man

- Dumfries Museum and Camera Obscura, Scotland

- Trondheim, Norway

- Lisbon and Tavira in Portugal

- Santa Monica, California at Pacific Palisades Park

- Los Angeles at the Griffith Observatory

- San Francisco, California's Camera Obscura

- North Carolina's "Cloud Chamber for the Trees and Sky"

- Havana in Cuba

- Eger in Hungary

- Cádiz in Spain in the Torre Tavira

- Great Orme at Llandudno in North Wales

- Royal Observatory, Greenwich, London

- Perdika , Aegina Island, Greece.

- Marburg , Universitie of Physik, Germany

- Stade, Germany[11][12]

- The Science Museum of Minnesota, St. Paul

- Greenport on Long Island, New York

- Children's Museum of Maine, Portland, Maine

- Sherman Hines Museum of Photography in Liverpool, Nova Scotia, Canada

- Douglas Head Camera Obscura in Douglas, Isle of Man

There is also a portable example which Willett & Patteson tour around England and the world.

The fully mobile photography centre Photomobile [1] contains a darkroom digital suit and camera obscura producing a six feet by four feet image. This unit is available for hire to educational establishments and arts events throughout the UK.

[edit] See also

[edit] Notes

- ^ Needham, Joseph. (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 1, Physics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. Page 82.

- ^ a b (Wade & Finger 2001)

- ^ David H. Kelley, Exploring Ancient Skies: An Encyclopedic Survey of Archaeoastronomy:

"The first clear description of the device appears in the Book of Optics of Alhazen."

- ^ (Wade & Finger 2001):

"The principles of the camera obscura first began to be correctly analysed in the eleventh century, when they were outlined by Ibn al-Haytham."

- ^ The Camera Obscura : Aristotle to Zahn

- ^ Adventures in CyberSound: The Camera Obscura

- ^ Bradley Steffens (2006), Ibn al-Haytham: First Scientist, Chapter Five, Morgan Reynolds Publishing, ISBN 1599350246

- ^ a b c d Needham, Volume 4, Part 1, 98.

- ^ BBC - The Camera Obscura

- ^ History of Photography and the Camera - Part 1: The first photographs

- ^ http://www.stade-tourismus.de/de/1/entdecken/75/kultur_mehr/416/camera_obscura_stadea/

- ^ http://www.fotoclub-das-auge.de/index.php?id=camera_obscura

[edit] References

- Hill, Donald R. (1993), ‘Islamic Science and Engineering’, Edinburgh University Press, page 70.

- Lindberg, D.C. (1976), ‘Theories of Vision from Al Kindi to Kepler’, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London.

- Nazeef, Mustapha (1940), ‘Ibn Al-Haitham As a Naturalist Scientist’, in Arabic, published proceedings of the Memorial Gathering of Al-Hacan Ibn Al-Haitham, 21 December 1939, Egypt Printing.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 1, Physics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Omar, S.B. (1977). ‘Ibn al-Haitham's Optics’, Bibliotheca Islamica, Chicago.

- Wade, Nicholas J.; Finger, Stanley (2001), "The eye as an optical instrument: from camera obscura to Helmholtz's perspective", Perception 30 (10): 1157–1177, doi:

[edit] External links

- An Appreciation of the Camera Obscura

- The Camera Obscura in San Francisco — The Giant Camera of San Francisco at Ocean Beach, added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2001

- Camera Obscura and World of Illusions, Edinburgh

- Dumfries Museum & Camera Obscura, Dumfries, Scotland

- Vermeer and the Camera Obscura by Philip Steadman

- Paleo-camera - The camera obscura and the origins of art

- List of all known Camera Obscura

- Re-opened camera obscura on Eastbourne Pier, UK

- Willett & Patteson Camera Obscura hire and Creation.

- Camera Obscura and Outlook Tower, Edinburgh, Scotland

- Cameraobscuras.com George T Keene builds custom camera obscuras like the Griffith Observatory CO in Los Angeles.

- Camera obscura in Trondheim, Norway Built by students of architecture and engineering from NTNU (The Norwegian University of Science and Technology)

- [2] Desolate Metropolis Photography